Stockdale v Hansard

Stockdale v Hansard (1839) 9 Ad & El 1 is a United Kingdom constitutional law case in which the Parliament of the United Kingdom unsuccessfully challenged the common law of parliamentary privilege, leading to legislative reform.

| Stockdale v. Hansard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Queen's Bench |

| Full case name | John Joseph Stockdale v. James Hansard, Luke Graves Hansard, Luke James Hansard, and Luke Henry Hansard |

| Decided | 31 May 1839 |

| Citation(s) | (1839) 9 Ad & Ell 96; 112 ER 1112; [1839] EWHC QB J21 |

| Transcript(s) | Transcript of judgment at bailii.org |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | Stockdale v. Hansard (1837) 3 St. Tr. (N.S.) 723 |

| Subsequent action(s) | — |

| Case opinions | |

| Denman CJ; Littledale, Patteson and Coleridge JJ | |

| Court membership | |

| Judge(s) sitting |

|

Facts

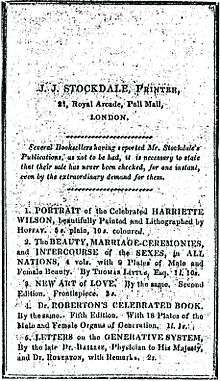

The Prisons Act 1835 had introduced the first national prison system in the United Kingdom, along with a regime of prison inspections. Whitworth Russell was one of the first inspectors and had been the reforming champion of the austere regime at the Millbank penitentiary.[1] In Newgate prison, Russell and his fellow inspector, William Crawford, had discovered a well-thumbed edition of John Roberton's On Diseases of the Generative System (1811), edited by Thomas Little, a pseudonym of John Joseph Stockdale. Roberton was a radical and something of an outsider to the medical profession, and Stockdale was a notorious pornographer. The book had attracted some distaste on its publication for its explicit anatomical plates.[2]

In 1836, the official parliamentary reporter Hansard, by order of the House of Commons, printed and published a report stating that an indecent book published by a Mr. Stockdale was circulating in Newgate. Publication of such parliamentary papers for circulation among Members of Parliament (MPs) alone was and, as of 2019 remains, protected by absolute privilege under common law.[3] However, a further development from 1835 had resulted from MP Joseph Hume's campaign to make better use of the mass of parliamentary papers and to improve freedom of information by publishing parliamentary papers to the public.[1]

The aldermen of the City of London who were responsible for Newgate were incensed. They saw Roberton's book as a scientific work, but the inspectors affirmed their original description by observing, "We also applied to several medical booksellers, who all gave it the same character. They described it as 'one of Stockdale's obscene books'".[1]

Stockdale sued for £500 damages for libel, admitting that he had published the book but denying its obscenity. Stockdale sued as a pauper and Mr Justice Park assigned him counsel. Attorney-General Sir John Campbell appeared for Hansard. The first trial took place in 1837 before Lord Denman and a jury.

Denman dismissed Campbell's defence that the publication was privileged, and the jury had to consider only the defence that the published statement had been true and the book was indeed indecent. When they first returned, the jury foreman said that it found the book indecent and obscene but did not all agree that it was disgusting and that it wished to award Stockdale a farthing in damages. After a rebuke from Lord Denman on its faulty logic, the jury briefly conferred and found for Hansard.[1]

Stockdale now found a copy of the City aldermen's response to the original report and sued again,[1] but Hansard was ordered by the House to plead that he had acted under order of the Commons and was protected by parliamentary privilege.

Judgment

The Commons claimed that:

- The Commons was a court superior to any court of law;

- Each House (Commons and Lords) was the sole judge of its own privileges;

- A resolution of the House declaratory of its own privileges could not be questioned in any court of law.

The court was led by Lord Denman, who had had some support on the case from barrister Charles Rann Kennedy.[4] The court held that only the Crown in both Houses of Parliament could make or unmake laws and no resolution of one house alone was beyond the control of law. Further, where it was necessary to establish the rights of those outside Parliament, the courts would decide the nature of privilege. The court found that the House held no privilege to order publication of defamatory material outside Parliament.[1][5][6]

In consequence,[7] Parliament passed the Parliamentary Papers Act 1840 to establish privilege for publications under the House's authority.

See also

References

- Stockdale, E. (1990)

- McGrath (2002)

- Lake v. King (1667) 1 Saunders 131

- Pue, W. W. (1990). "Moral panic at the English Bar: Paternal vs. commercial ideologies of legal practice in the 1860s". Law and Social Inquiry. 15 (1): 62. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.1990.tb00275.x.

- Bradley & Ewing (2003) pp. 219–220

- P., Ford; Ford, G., eds. (1962). Luke Graves Hansard's Diary 1814–1841. Oxford: Blackwell.

- "A year after the judgment of the King's Bench in the Stockdale v Hansard case ... the Anglo-Saxon legal system adapted to the latitude of the protection, established there, for the subjects that operated under parliamentary privilege, foreseeing by law the subtraction to responsibility also of the documents printed by the Parliament (the Parliamentary Papers Act 1840)": transl. by (in Italian) Giampiero Buonomo, La Cassazione giudice dell'attrazione in autodichia, Questione giustizia, 17 settembre 2019.

Bibliography

- Bradley, A.W. & Ewing, K.D. (2003). Constitutional and Administrative Law (13th ed.). London: Pearson. pp. 219–220. ISBN 0-582-43807-1.

- Loveland, I. (2000). Political Libels: A Comparative Study. London: Hart Publishing. pp. 21–22. ISBN 1-84113-115-6. (Google Books)

- McGrath, R. (2002). Seeing Her Sex: Medical Archives and the Female Body. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. Ch.2. ISBN 0-7190-4167-8. (Google Books)

- Stockdale, E. (1990). "The unnecessary crisis: The background to the Parliamentary Papers Act 1840". Public Law: 30–49.

- Select Committee on Publication of Printed Papers (8 May 1837), Report with the Minutes of Evidence, and Appendix, House of Commons sessional papers, XIII, 286, p. 97, retrieved 2 June 2017