Steamboats of the Willamette River

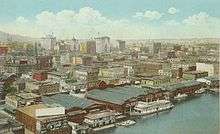

The Willamette River flows northwards down the Willamette Valley until it meets the Columbia River at a point 101 miles[1] from the Pacific Ocean, in the U.S. state of Oregon.

.jpeg)

Route and early operations

| Location | Distance |

|---|---|

| Portland (Steel Bridge) |

12 mi (19 km) |

| Milwaukie | 19 mi (31 km) |

| Clackamas River | 25 mi (40 km) |

| Oregon City (Willamette Falls) |

27 mi (43 km) |

| Canemah | 28 mi (45 km) |

| Tualatin River | 29 mi (47 km) |

| Butteville | 42 mi (68 km) |

| Champoeg | 46 mi (74 km) |

| Yamhill River | 55 mi (89 km) |

| Carey Bend | 58 mi (93 km) |

| Tompkins Bar | 69 mi (111 km) |

| Darrow Chute | 80 mi (130 km) |

| Salem | 85 mi (137 km) |

| Gray Eagle Bar | 89 mi (143 km) |

| Independence | 96 mi (154 km) |

| Santiam River | 108 mi (174 km) |

| Black Dog Bar | 112 mi (180 km) |

| Albany | 120 mi (190 km) |

| Corvallis | 132 mi (212 km) |

| Kiger Island | 135 mi (217 km) |

| Norwood Island | 150 mi (240 km) |

| Harrisburg | 163 mi (262 km) |

| Eugene | 185 mi (298 km) |

In the natural condition of the river, Portland was the farthest point on the river where the water was deep enough to allow ocean-going ships. Rapids further upstream at Clackamas were a hazard to navigation, and all river traffic had to portage around Willamette Falls, where Oregon City had been established as the first major town inland from Astoria.

The first steamboat built and launched on the Willamette was Lot Whitcomb, launched at Milwaukie, Oregon, in 1850. Lot Whitcomb was 160 feet (49 m) long, had 24-foot (7.3 m) beam, 5 feet (1.5 m) of draft, and 600 gross tons.[3] Her engines were designed by Jacob Kamm, built in the eastern United States, then shipped in pieces to Oregon.[4] Her first captain was John C. Ainsworth, and her top speed was 12 miles per hour (19 km/h).[4] Lot Whitcomb was able to run upriver 120 miles (190 km) from Astoria to Oregon City in ten hours, compared to the Columbia's two days. She served on the lower river routes until 1854, when she was transferred to the Sacramento River in California, and renamed the Annie Abernathy.[3]

The side-wheeler Multnomah made her first run in August 1851, above Willamette Falls. She had been built in New Jersey, taken apart into numbered pieces, shipped to Oregon, and reassembled at Canemah, just above Willamette Falls. She operated above the falls for a little less than a year, but her deep draft barred her from reaching points on the upper Willamette, so she was returned to the lower river in May 1852, where for the time she had a reputation as a fast boat, making for example the 18-mile (29 km) run from Portland to Vancouver, Washington in one hour and twenty minutes.[5]

Another sidewheeler on the Willamette River at this time was the Mississippi-style Wallamet, which did not prosper, and was sold to California interests.[6] In 1853, the side-wheeler Belle of Oregon City, an iron-hulled boat built entirely in Oregon, was launched at Oregon City. Belle (as generally known) was notable because everything, including her machinery, was of iron that had been worked in Oregon at a foundry owned by Thomas V. Smith. Belle lasted until 1869, and was a good boat, but was not considered a substitute for the speed and comfort (as the standard was then) of the departed Lot Whitcomb.[6]

Also operating on the river at this time were James P. Flint, Allen, Washington, and the small steam vessels Eagle, Black Hawk, and Hoosier, the first two being iron-hulled and driven by propellers.[5][6]

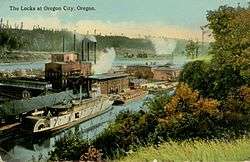

Canal and locks at Willamette Falls

Locks were completed at Willamette Falls in 1873.[1] This eliminated the need for the portage at Willamette Falls and established an "open river" all the way south to Eugene, although the water was so shallow by that point that few boats ever made it so far.

Lock and dam on Yamhill River

In 1900 a Yamhill River lock and dam lock and dam was completed about 1.5 miles downriver from Lafayette, Oregon. The lock was decommissioned in 1954. The dam was deliberately destroyed in 1963 to allow better passage for salmon on the river. The site of the lock and dam is now a county park.

Operations on Willamette River

The Willamette River was readily navigable by steamboats all the way up to Milwaukie. Above Milwaukie, there were two barriers to navigation, the Clackamas Rapids and Willamette Falls. The Clackamas Rapids were navigable, provided the steamboat was small and light. Willamette Falls was impassable. All traffic bound upriver had to portage around Willamette Falls at Oregon City.

Steam powered vessels did not operate on the Willamette River above Willamette Falls until 1851. Other than the small Hoosier, a converted ship's long boat with a pile driver engine, the first boat on the Willamette above the falls was the Canemah, built at the town of the same name and launched towards the end of September, 1851. Her owner was Absalom F. Hedges, the founder of Canemah. Canemah proved to be a profitable boat, she got the contract for carrying mail upriver, and earned 20 cents a bushel hauling grain downriver from Corvallis to Canemah. A boat of her size could load 1,000 to 1,500 bushels a trip. Multnomah, prefabricated back east and shipped out to Oregon, was apparently assembled at Canemah and launched about the same time as the steamer Canemah. She operated on the Willamette and also on the Yamhill River as far up as Dayton. Multnomah's draft was too deep for the upper stretches of the Willamette (where the real money could be made hauling cargo) and so in May 1852, she was portaged over the falls to operate in the lower Willamette and Columbia rivers.[5]

Operations on tributaries

_on_Willamette_River%2C_circa_1910.jpg)

Oswego Lake and Tualatin River

Sucker Lake, later called Oswego Lake, is a large lake south of Portland, about half the distance to Oregon City. (The current Oswego Lake is a larger version of the original lake, formed by a dam on the east end.) The Tualatin River is a tributary of the Willamette River, which runs near to the west end of Oswego Lake, which itself is tributary to the Willamette, draining easterly through Sucker Creek, now known as Oswego Creek. In 1865, John Corse Trullinger established a sawmill driven by an overshot waterwheel on Sucker Creek. At that time, road and other access to the Tualatin Valley was very difficult. The mouth of the Tualatin River was unnavigable, so it was necessary to portage around the Tualatin's mouth to get to a place where steamboats could run.[5]

Starting on May 29, 1865 a portage mule-hauled railroad on wooden tracks ran between the Tualatin River and Sucker Lake, a distance of about 1.75 miles (2.82 km). This was called the Sucker Lake and Tualatin River Railroad. The main traffic was logs for Trullinger's mill on the east end of Sucker Lake. The steam sidewheel scow Yamhill, under Captain Edward Kellogg (brother of Joseph Kellogg), was then running on the Tualatin, as a replacement for the Hoosier. The owners of the railroad, together with the People's Transportation Company, decided to use the lake route and establish improved communications with the Tualatin Valley, and so, in the summer of 1866, they built the steamer Minnehaha at Oswego.[5]

Through the 1870s, Minnehaha ran on the lake, connecting to Colfax Landing at the west end. Traffic would there be portaged over to the Tualatin, where, starting in 1869, the small sternwheeler Onward, 100 tons, served points as far as 60 miles (97 km) upstream to head of navigation at Emerick's Landing. Onward made one trip up and one trip down the Tualatin every week. A trip from Portland on this route would begin at the Ash Street dock on Wednesday evening by boarding the Senator, bound for Oswego, where travelers would stay Wednesday night at Shade's Hotel. They would then board the Onward, proceed west down Sucker Lake, to the portage railroad at Colfax Landing. Mules or horses would draw wagons carrying the passengers and freight over to the Tualatin, where the travelers would reembark, and the cargo be reloaded, for points upstream. The return journey to Portland would be the reverse, but would start on Sunday evening. There were many landings along the way, ones whose names survive into modern times include Taylor's Ferry (later, Taylor's Bridge), Scholl's, Scholl's Ferry, Farmington, Hillsboro and Forest Grove.[5]

In 1871, the Tualatin River Navigation & Manufacturing Company began work to complete a continuous navigable waterway from the Tualatin to the Willamette. The company planned to build two canals: one to connect the Tualatin River to Sucker Lake with access to the iron smelter located on its east end; and a second with locks that would connect Sucker Lake to the Willamette via Sucker Creek.[7] The first canal was finished in 1872, but due to low water, was not passed through until January 21, 1873, when Onward made the first trip.[5][7]

With the completion of the Willamette Falls Locks in 1873, and with navigation of the Tualatin River already difficult due to its low water and numerous snags and sinkers, the second canal was never built and the idea of a Sucker Lake passage was never realized.[7] After 1890, business fell off, particularly with the Panic of 1893. By 1895, when the Corps of Engineers declared the Tualatin unnavigable, there was not any river traffic on it anyway.[1][5]

Replica steamboats

In much more recent decades, starting in the early 1980s, a number of replica steamboats have been built, for use as tour boats in river cruise service on the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. Although still configured as sternwheelers, they are non-steam-driven boats or ships, also called motor vessels, powered instead by diesel engines. These tourism-focussed vessels range in size from the 65-foot (20 m) Rose to the 360-foot (110 m) American Empress (formerly Empress of the North). Others include the M.V. Columbia Gorge, the Willamette Queen, and the Queen of the West.

See also

Notes

- Timmen, Fritz, Blow for the Landing, at 89–90, 228, Caxton Printers, Caldwell, ID 1972 ISBN 0-87004-221-1

- Timmen, Fritz (1973). "Distance Tables". Blow for the Landing -- A Hundred Years of Steam Navigation on the Waters of the West. Caldwell, ID: Caxton Printers. pp. 228, 229. ISBN 0-87004-221-1. LCCN 73150815.

- Affleck, Edward L., A Century of Paddlewheelers in the Pacific Northwest, the Yukon, and Alaska, at 18, Alexander Nicholls Press, Vancouver, B.C. 2000 ISBN 0-920034-08-X

- Gulick, Bill, Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, Caxton Press, at 23, Caldwell, Idaho (2004) ISBN 0-87004-438-9

- Corning, Howard McKinley, Willamette Landings, (2nd Ed.), at 62, 117–119, and 171-78, Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR 1973 ISBN 0-87595-042-6

- Mills, Randall V., Sternwheelers up Columbia, at 21, 25–26, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, NE 1947 ISBN 0-8032-5874-7

- Fulton, Ann (2002). Iron, Wood & Water: An Illustrated History of Lake Oswego. San Antonio, Texas: Historical Publishing Network and the Oswego Heritage Council. p. 33. ISBN 1-893619-26-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Steamboats of the Willamette River. |

Oregon State University image collection

Salem Public Library image collection

- Claude Skinner's steam launch, 1958

- Willamette Chief and other vessels, at landing somewhere on Columbia River

- Three Sisters, 1890s

- Grahamona being built at East Portland, 1912

- Gamecock, renamed Gay Marie and converted to floating apartment house, Nov 12, 1945, in a sinking condition

- Hall at Champoeg, with nameboards of steamboats