Steamboats of the Mississippi

Steamboats played a major role in the 19th-century development of the Mississippi River and its tributaries by allowing the practical large-scale transport of passengers and freight both up- and down-river. Using steam power, riverboats were developed during that time which could navigate in shallow waters as well as upriver against strong currents. After the development of railroads, passenger traffic gradually switched to this faster form of transportation, but steamboats continued to serve Mississippi River commerce into the early 20th century. A small number of steamboats are used for tourist excursions into the 21st century.

Geography

The Mississippi is one of the world’s great rivers. It spans 3,860 miles (6,210 km) of length as measured using its northernmost west fork, the Missouri River, which starts in the Rocky Mountains in Montana, joining the Mississippi proper in the state of Missouri. The Ohio River and Tennessee River are other tributaries on its east, and the Arkansas, Platte and Red River of Texas on the west. The Mississippi itself starts at Lake Itasca in Minnesota, and the river wends its way through the center of the country, forming parts of the boundaries of ten states, dividing east and west, and furthering trade and culture.

Background

Steamboats on the Mississippi benefited from technology and political changes. The US bought the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. At the time, a semi-bankrupt Napoleon was attempting to extend his hegemony over Europe in what came to be known as the Napoleonic Wars. As a result, the US was then free to expand westward out of the Ohio valley and into the Great Plains and the Southwest. The success of the Charlotte Dundas in Scotland in 1801 and Robert Fulton's Clermont on the Hudson River in 1807 proved the concept of the steamboat. At this time, walking beam mill engines, of the Boulton and Watt variety, were dropped onto wood barges with paddles to create an instant powerboat. The overhead engines of the "walking beam" type became the standard Atlantic Seaboard paddle engine for the next 80 years. For smaller boats, Watt perfected the side-lever engine with the engine cut down using side bell-cranks to lower the center of gravity. Sidewheel paddlers were the first to enter the scene. In 1811 the steamer New Orleans was built in Pittsburgh for Fulton and Livingston. Fulton started steamboat service between Natchez and New Orleans.

The War of 1812 caused political upheaval in the south, particularly with the Royal Navy blockade of the US Gulf Coast ports but after the Treaty of Ghent and resumption of peace, New Orleans was firmly American, after passing through French and Spanish hands. New Orleans became the great port on the mouth of the Mississippi.

Golden age of steamboats

The historical roots of the prototypical Mississippi steamboat, or Western Rivers steamboat, can be traced to designs by easterners like Oliver Evans, John Fitch, Daniel French, Robert Fulton, Nicholas Roosevelt, James Rumsey and John Stevens.[1][2] In the span of just six years the evolution of the prototypical Mississippi steamboat would be well underway.

- New Orleans, or Orleans, was the first Mississippi steamboat.[3] Launched in 1811 at Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania for a company organized by Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton, her designer, she was a large, heavy side-wheeler with a deep draft.[1][4][5] Her low-pressure Boulton and Watt steam engine operated a complex power train that was also heavy and inefficient.[1]

- Comet was the second Mississippi steamboat.[6] Launched in 1813 at Pittsburgh for Daniel D. Smith, she was much smaller than the New Orleans.[7] With an engine and power train of Daniel French's design and manufacture, the Comet was the first Mississippi steamboat to be powered by a light weight and efficient high-pressure engine turning a stern paddle wheel.[8]

- Vesuvius was the third Mississippi steamboat.[9] Launched in 1814 at Pittsburgh for the company headed by Robert Livingston and Robert Fulton, her designer, she was very similar to the New Orleans.[10]

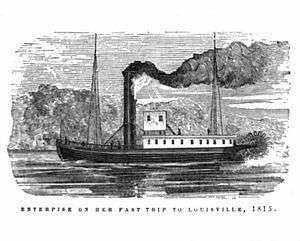

- Enterprise, or Enterprize, was the fourth Mississippi steamboat.[11] Launched in 1814 at Brownsville, Pennsylvania for the Monongahela and Ohio Steam Boat Company, she was a dramatic departure from Fulton's boats.[1] The Enterprise - featuring a high-pressure steam engine, a single stern paddle wheel, and shoal draft - proved to be better suited for use on the Mississippi than Fulton's boats.[1][12][13] The Enterprise clearly demonstrated the suitability of French's design during her epic voyage from New Orleans to Brownsville, a distance of more than 2,000 miles (3,200 km) performed against the powerful currents of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers.[14]

- Washington was launched in 1816 at Wheeling, West Virginia for Henry Shreve and partners.[15] George White built the boat and Daniel French constructed the engine and drive train at Brownsville.[16] She was the first steamboat with two decks, the predecessor of the Mississippi steamboats of later years.[12] The upper deck was reserved for passengers and the main deck was used for the boiler, increasing the space below the main deck for carrying cargo.[12] With a draft of 4 feet (1.2 m), she was propelled by a high-pressure, horizontally mounted engine turning a single stern paddle wheel.[12] In the spring of 1817 the Washington made the voyage from New Orleans to Louisville in 25 days, equalling the record set two years earlier by the Enterprise, a much smaller boat.[17]

.jpg)

In the 1810s there were 20 boats on the river; by the 1830s there were more than 1200. By the 1820s, with the Southern states joining the Union and the land converted to cotton plantations so indicative of the Antebellum South, methods were needed to move the bales of cotton, rice, timber, tobacco, and molasses. The steamboat was perfect. America boomed in the age of Jackson. Population moved west, and more farms were established. In the 1820s steamers were fueled first by wood, then coal, which pushed barges of coal from Pittsburgh to New Orleans. Regular steamboat commerce began between Pittsburgh and Louisville.

Construction of the vessels

Vessels were made of wood—typically ranging in length from 40 to nearly 300 feet (91 m) in length, 10 to 80 feet (24 m) wide, drawing only about one to five feet of water loaded, and in fact it was commonly said that they could "navigate on a heavy dew." [19] The boats had kingposts or internal masts to support hogchains, or iron trusses, which prevented the hull from sagging. A second deck was added, the Texas Deck, to provide cabins and passenger areas. All was built from wood. Stairs, galleys, parlors were also added. Often the boats became quite ornate with wood trim, velvet, plush chairs, gilt edging and other trimmings sometimes featured as per the owner's taste and budget. Wood burning boilers were forward center to distribute weight. The engines were also amidships, or at the stern depending on if the vessel was a sternwheeler or sidewheeler. Two rudders were fitted to help steer the ship.

Vessels, on average, only lasted about five years due to the wooden hulls being breached, poor maintenance, fires, general wear and tear, and the common boiler explosion. Early trips up the Mississippi River took three weeks to get to the Ohio. Later, with better pilots, more powerful engines and boilers, removal of obstacles and experienced rivermen knowing where the sand bars were, the figure was reduced to 4 days. Collisions and snags were constant perils.

The steamers Natchez

Natchez I

The first Natchez was a low pressure sidewheel steamboat built in New York City in 1823. It originally ran between New Orleans and Natchez, Mississippi, and later catered to Vicksburg, Mississippi. Its most notable passenger was Marquis de Lafayette, the French hero of the American Revolutionary War, in 1825. Fire destroyed it, while in New Orleans, on September 4, 1835.

Natchez II

Natchez II was the first built for Captain Thomas P. Leathers, at Crayfish Bayou, and ran from 1845 to 1848. It was a fast two-boiler boat, 175 feet (53 m) long, with red smokestacks, that sailed between New Orleans and Vicksburg, Mississippi. It was built in Cincinnati, Ohio, Leathers sold it in 1848. It was abandoned in 1852.

Natchez III

Natchez III was funded by the sale of the first. It was 191 feet (58 m) long. Leathers operated it from 1848 to 1853. On March 10, 1866, it sank at Mobile, Alabama due to rotting.

Natchez IV

Natchez IV was built in Cincinnati, Ohio. It was 270 feet (82 m) long, had six boilers, and could hold 4,000 bales of cotton. It operated for six weeks. On January 1, 1854, the ship collided with the Pearl at Plaquemine, Louisiana, causing the Pearl to sink. A wharf fire on February 5, 1854 at New Orleans caused it to burn down, as did 10-12 other ships.

Natchez V

Natchez V was also built in Cincinnati, as Captain Leathers returned there quickly after the destruction of the third. It was also six boilers, but this one could hold 4,400 cotton bales. This one was used by Leathers until 1859. In 1860 it was destroyed while serving as a wharfboat at Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Natchez VI

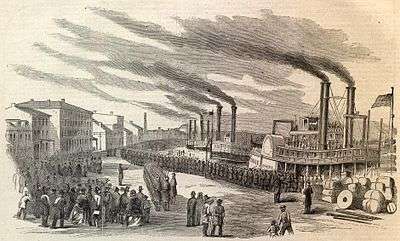

Natchez VI was again a Cincinnati-built boat. It was 273 feet (83 m) long. The capacity was 5,000 cotton bales but the power remained the same. It helped transport Jefferson Davis from his river plantation home on the Mississippi River after he heard he was chosen president of the Confederacy. Even after the war, Davis would insist on using Leather's boats to transport him to and from his plantation, Brierfield. Natchez VI was also used to transport Confederate troops to Memphis, Tennessee. After Union invaders captured Memphis, the boat was moved to the Yazoo River. On March 13, 1863, it was burned either by accident or to keep it out of Union hands at Honey Island. Remains were raised from the river in 2007.

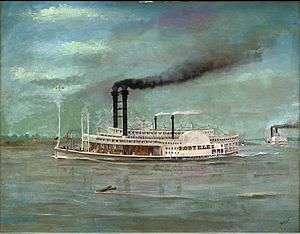

Natchez VIII

Natchez VIII was launched August 2, 1879 by the Cincinnati Marine Ways. It was 303.5 feet (92.5 m) long, with a beam of 45.5 feet (13.9 m), 38.5 feet (11.7 m) floor, and 10 feet (3.0 m) hold depth. It had eight steel boilers that were 36 feet (11 m) long and had a diameter of 42 inches (1,100 mm), and thirteen engines. It had 47 elegant staterooms. Camp scenes of Natchez Indians wardancing and sunworshipping ornamented the fore and aft panels of the main cabin, which also had stained glass windows depicting Indians. The total cost of the boat was $125,000. Declaring that the War was over, on March 4, 1885, Leathers raised the American flag when the new Natchez passed by Vicksburg, the first time he hoisted the American flag on one of his ships since 1860. By 1887 lack of business had stymied the Natchez. In 1888 it was renovated back to perfect condition for $6000. In January 1889 it burned down at Lake Providence, Louisiana. Captain Leathers, deciding he was too old to build a new Natchez, retired. Jefferson Davis sent a letter of condolences on January 5, 1889, to Leathers over the loss of the boat. Much of the cabin was salvageable, but the hull broke up due to sand washing within.

Improved navigation

In 1824 Congress passed an "Act to Improve the Navigation of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers" and "to remove sand bars on the Ohio and planters, sawyers, and snags on the Mississippi". The Army Corps of Engineers was given the job. In 1829, there were surveys of the two major obstacles on the upper Mississippi, the Des Moines Rapids and the Rock Island Rapids, where the river was shallow and the riverbed was rock. The Des Moines Rapids were about 11 miles (18 km) long and, traveling upriver, began just above the mouth of the Des Moines River at Keokuk, Iowa. The Rock Island Rapids were between Rock Island and Moline, Illinois. Both rapids were considered virtually impassable. The Army Corps of Engineers recommended the excavation of a 5 ft (1.5 m) deep channel at the Des Moines Rapids, but work did not begin until after Lieutenant Robert E. Lee endorsed the project in 1837. In 1848, the Illinois and Michigan Canal was built to connect the Mississippi River to Lake Michigan via the Illinois River near Peru, Illinois. The Corps later also began excavating the Rock Island Rapids. By 1866, it had become evident that excavation was impractical, and it was decided to build a canal around the Des Moines Rapids. That canal opened in 1877, but the Rock Island Rapids remained an obstacle.

St. Louis

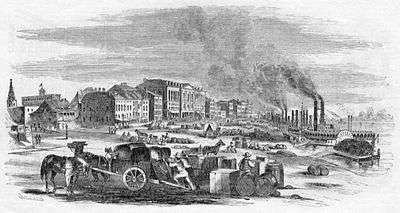

St. Louis became an important trade center, not only for the overland route for the Oregon and California trails, but as a supply point for the Mississippi. Rapids north of the city made St. Louis the northernmost navigable port for many large boats. The Zebulon Pike and his sisters soon transformed St. Louis into a bustling boom town, commercial center, and inland port. By the 1830s, it was common to see more than 150 steamboats at the St. Louis levee at one time. Immigrants flooded into St. Louis after 1840, particularly from Germany. During Reconstruction, rural Southern blacks flooded into St. Louis as well, seeking better opportunity. By the 1850s, St. Louis had become the largest U. S. city west of Pittsburgh, and the second-largest port in the country, with a commercial tonnage exceeded only by New York. James Eads was a famed engineer who ran a shipyard and first built riverboats in the 1850s, then armed riverboats and finally the legendary bridge over the Mississippi. His Mound City Ironworks and shipyard was famous, and featured often in the naming of vessels.

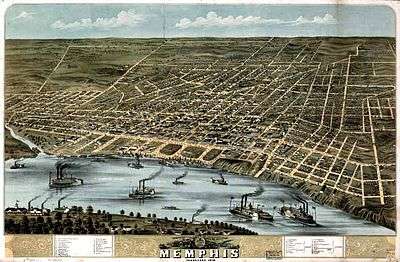

Memphis

Memphis became another major port on the Mississippi. It was the slave port. Hence the city was contested in the Civil War.

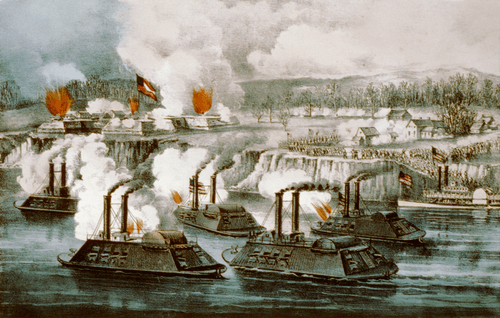

The First Battle of Memphis was a naval battle fought on the Mississippi River immediately above the city of Memphis on June 6, 1862, during the American Civil War. The engagement was witnessed by many of the citizens of Memphis. It resulted in a crushing defeat for the Rebels, and marked the virtual eradication of a Confederate naval presence on the river. Despite the lopsided outcome, the Union Army failed to grasp its strategic significance. Its primary historical importance is that it was the last time civilians with no prior military experience were permitted to command ships in combat.

Tom Lee Park on the Memphis riverfront is named for an African-American riverworker who became a civic hero. Tom Lee could not swim. Nevertheless, he single-handedly rescued thirty-two people from drowning when the steamer M.E. Norman sank in 1925.

Washington, Louisiana

Washington, Louisiana, is not located directly on the Mississippi River; it is more than 30 miles west of the Mississippi on Bayou Courtableau. Nevertheless, the port there was the largest between New Orleans and St. Louis during much of the 19th century.[20] Products such as cotton, sugar, and livestock were brought to Washington overland or by small boat and then transferred to the steam packets for shipment to New Orleans. By the mid-19th century, Washington developed a thriving trade and became the most important port in the vicinity of St. Landry Parish. This can be seen in the number of steamers that used the port and in the volume of freight. In 1860 there were 93 steam packets operating in the Bayou Courtableau trade, as compared with 90 in Bayou Lefourche and 94 in Bayou Teche. An 1877 tabulation showed the total quantity of goods shipped from Washington to New Orleans: 30,000 bales of cotton, 32,000 sacks of cotton seed, 3,000 hogsheads of sugar, 5,800 barrels of molasses, 30,000 dozen poultry, As many as 93 packets came to Washington during the steamboat era which ended in 1900.

Mark Twain

Many of the works of Mark Twain deal with or take place near the Mississippi River. One of his first major works, Life on the Mississippi, is in part a history of the river, in part a memoir of Twain's experiences on the river, and a collection of tales that either take place on or are associated with the river. Twain's most famous work, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, is largely a journey down the river. The novel works as an episodic meditation on American culture with the river having multiple different meanings including independence, escape, freedom, and adventure.

Twain himself worked as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi for a few years. A steamboat pilot needed a vast knowledge of the ever-changing river to be able to stop at any of the hundreds of ports and wood-lots along the river banks. Twain meticulously studied 2,000 miles (3,200 km) of the Mississippi for two and a half years before he received his steamboat pilot license in 1859. While training, he convinced his younger brother Henry to work with him. Henry died on June 21, 1858, when the steamboat he was working on, the Pennsylvania, exploded.

Boiler explosions

In the forty years to the mid-century mark, there were some 4,000 fatalities on the river due to boiler explosions. Some 500 vessels were wrecked by the peril. Early boilers were riveted of weak iron plate. Vessels at the time were not inspected, or insured. Passengers were on their own. Meanwhile, the explosions continued: the Teche in 1825, with sixty killed; the Ohio and the Macon in 1826; the Union and the Hornet in 1827; the Grampus in 1828; the Patriot and the Kenawa in 1829; the Car of Commerce and the Portsmouth in 1830; the Moselle in 1838.

Mark Twain noted a bad boiler explosion which occurred aboard the steamboat Pennsylvania in 1858. Among the injured passengers was Henry Clemens, his brother, whose skin had been badly scalded. Twain came to visit Henry in an improvised hospital. This is how he described the long painful death of his brother: "For forty-eight hours I labored at the bedside of my poor burned and bruised but uncomplaining brother...and then the star of my hope went out and left me in the gloom of despair..."

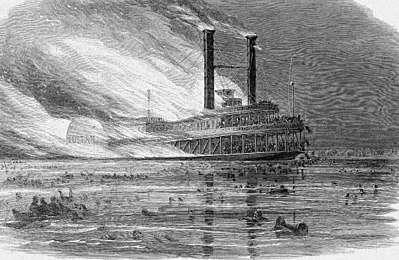

On February 24, 1830, as the Helen McGragor prepared to pull away from the Memphis waterfront, the starboard boiler blew. The blast itself and flying debris killed a number of people, and about thirty others were scalded to death. The boiler explosions and resulting fire aboard the Sultana in 1865 (near Memphis) led to at least 1192 deaths and is considered the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history.

Gambling

Gambling took many forms on riverboats. Gambling with one's life with the boilers aside, there were sharks around willing to fleece the unsuspecting rube. As cities passed ordinances against gaming houses in town, the cheats moved to the unregulated waters of the Mississippi aboard river steamers.

There was also gambling with the racing of boats up the river. Bets were made on a favorite vessel. Pushing the boilers hard in races would also cause fires to break out on the wooden deck structures.

Regulation

One of the enduring issues in American government is the proper balance of power between the national government and the state governments. This struggle for power was evident from the earliest days of American government and is the underlying issue in the case of Gibbons v. Ogden. In 1808, Robert Fulton and Robert Livingston were granted a monopoly from the New York state government to operate steamboats on the state's waters. This meant that only their steamboats could operate on the waterways of New York, including those bodies of water that stretched between states, called interstate waterways. This monopoly was very important because steamboat traffic, which carried both people and goods, was very profitable. Aaron Ogden held a Fulton-Livingston license to operate steamboats under this monopoly. He operated steamboats between New Jersey and New York. However, another man named Thomas Gibbons competed with Aaron Ogden on this same route. Gibbons did not have a Fulton-Livingston license, but instead had a federal (national) coasting license, granted under a 1793 act of Congress.

The United States at this time was a loose confederation of states. The federal government was weak, and so regulating vessels, even for gaming statutes, was an imposition on States Rights. The Interstate Steamboat Commerce Commission was finally set up in 1838 to regulate steamboat traffic. Boiler inspections only began in 1852.

Steamboat Act of May 30, 1852

The 1838 law proved inadequate as steamboat disasters increased in volume and severity. The 1847 to 1852 era was marked by an unusual series of disasters primarily caused by boiler explosions, however, many were also caused by fires and collisions. These disasters resulted in the passage of the Steamboat Act of May 30, 1852 (10 Stat. L., 1852) in which enforcement powers were placed under the Department of the Treasury rather than the Department of Justice as with the Act of 1838. Under this law, the organization and form of a federal maritime inspection service began to emerge. Nine supervisory inspectors were appointed, each of them responsible for a specific geographic region. There were also provisions for the appointment of local inspectors by a commission consisting of the local District Collector of Customs, the Supervisory Inspector, and the District Judge. The important features of this law were the requirement for hydrostatic testing of boilers, and the requirement for a boiler steam safety valve. This law further required that both pilots and engineers be licensed by the local inspectors. Even though time and further insight proved the Steamboat Act inadequate, it must be given credit for starting legislation in the right perspective. Probably the most serious shortcoming was the exemption of freightboats, ferries, tugboats and towboats, which continued to operate under the superficial inspection requirements of the law of 1838. Again, disasters and high loss of life prompted congressional action through the passage of the Act of February 28, 1871.

Showboats

A showboat (or show boat) was a form of theater that traveled along the waterways of the United States, especially along the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. A showboat was basically a barge that resembled a long, flat-roofed house, and in order to move down the river, it was pushed by a small tugboat (misleadingly labeled a towboat) which was attached to it. It would have been impossible to put a steam engine on it, since it would have had to have been placed right in the auditorium.

British-born actor William Chapman, Sr. created the first showboat, named the "Floating Theatre," in Pittsburgh in 1831. He and his family performed plays with added music and dance at stops along the waterways. After reaching New Orleans, they got rid of the boat and went back to Pittsburgh in a steam boat in order to perform the process once again the year after. Showboats had declined by the Civil War, but began again in 1878 and focused on melodrama and vaudeville. Major boats of this period included the New Sensation, New Era, Water Queen, and the Princess. With the improvement of roads, the rise of the automobile, motion pictures, and the maturation of the river culture, showboats declined again. In order to combat this development, they grew in size and became more colorful and elaborately designed in the 20th century. These boats included the Golden Rod, the Sunny South, the Cotton Blossom, the New Showboat, and the Minnesota Centennial Showboat. Jazzmen Louis Armstrong and Bix Biederbecke played on Mississippi River steamers.

In Oklahoma

As the federal government removed the Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek Nations to Oklahoma, the new immigrants and the military forces demanded supplies, creating a vigorous steamboat trade to the Mississippi River down to New Orleans or upstream to points north. At the peak of steamboat commerce, in the 1840s and 1850s, there were twenty-two landings between Fort Smith in present-day Arkansas, and Fort Gibson, with the most difficult point at Webbers Falls.

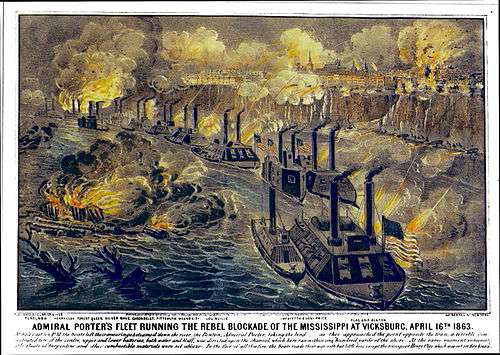

Civil War Service

The American Civil War spilled over to the Mississippi with naval sieges and naval war using paddlewheelers. The Battle of Vicksburg involved monitors and ironclad riverboats. The USS Cairo is a wrecked survivor of the Vicksburg battle. Trade on the river was suspended for two years because of a Confederate blockade. The triumph of Eads ironclads, and Farragut's seizure of New Orleans, secured the river for the Union North.

The worst of all steamboat accidents occurred at the end of the Civil War in April 1865, when the steamboat Sultana, carrying an over-capacity load of returning Union soldiers recently freed from Confederate prison camp, blew up, causing more than 1,000 deaths.[21]

Reconstruction

With the Union Victory and occupation of the south, transport was administered by the US Army and Navy. The year 1864 brought an all-time low water mark on Upper Mississippi mark for all subsequent measurements. Stern wheelers proved more adaptable than side wheelers for barges. Immediately after the war, passenger steamboats become larger, faster and floating palaces began to appear; on the freight barges salt, hay, iron ore, and grain were carried. A few boats specialized in pushing huge log rafts downstream to lumber mills. By 1850, a system of moving barges and log rafts lashed alongside and ahead of the towboat was developed which allowed greater control than towing on a hawser. This type of service favored sternwheel propelled boats over sidewheelers and promoted other improvements as well. Towboats became a distinct type by 1860. Sand and gravel for construction was dredged up from river bottoms, and pumped aboard cargo barges. Simple hydraulic dredging rigs on small barges did the work. Towboats moved the dredge and sand barges around as needed.

The Great Race

Natchez VII was built in 1869. It was 301 feet (92 m) long, had eight boilers and a 5,500 cotton bale capacity. In its 9 1⁄2-year service, it made 401 trips without a single deadly accident. It became famous as the participant against another Mississippi paddle steamer, the Robert E. Lee, in a race from New Orleans to St. Louis in June 1870, immortalized in a lithograph by Currier and Ives. This Natchez had beaten the previous speed record, that of the J. M. White in 1844. Stripped down, carrying no cargo, steaming on through fog and making only one stop, the Robert E. Lee won the race in 3 days, 18 hours and 14 minutes. By contrast, the Natchez carried her normal load and stopped as normal, tying up overnight when fog was encountered. Despite this she berthed only six hours later. When Leathers finally dismantled the boat in Cincinnati in 1879, this particular Natchez had never flown the American flag.[22]

Competition from the railroads

Railroads were rebuilt in the south after the Civil War, the disconnected small roads, of 5-foot (1.5 m) broad gauge, were amalgamated and enlarged into big systems of the southern Illinois Central and Louisville and Nashville. Track was changed to the American Standard of 4 feet 8 and one half inches. This ways cars could travel from Chicago to the south without having to be reloaded. Consequently, rail transport became cheaper than steamboats. The boats could not keep up. The first railroad bridge built across the Mississippi River connected Davenport and Rock Island, IL in 1856, built by the Rock Island Railroad. Steamboaters saw nationwide railroads as a threat to their business. On May 6, 1856, just weeks after it was completed, a pilot crashed the Effie Afton steamboat into the bridge. The owner of the Effie Afton, John Hurd, filed a lawsuit against The Rock Island Railroad Company. The Rock Island Railroad Company selected Abraham Lincoln as their trial lawyer.

Rise of barge traffic

Barge traffic exploded with the growth of trade from the First World War.

Freight tonnage on the Upper Mississippi fell below 1 million tons per year in 1916 and hovered around 750,000 tons until 1931. A number of factors had led to this decline. Log rafts and raft towboats had disappeared and river cargo service had shifted to short-haul instead of long distance hauling. The First World War made crewmen scarce and helped to make the railroads stronger. The deficiencies of railroad transportation during World War I led to the Transportation Act of 1920.

In spite of these problems, the heavy transportation needs of wartime could not be met by railroads and river transport took off some of the pressure. In 1917, the United States Shipping Board allocated $3,160,000 to the Emergency Fleet Corporation to build and operate barges and towboats on the Upper Mississippi. Federal control was augmented by the Federal Control Act of 1918. The U.S. Railroad Administration formed the Committee on Inland Waterways to oversee the work. All floating equipment on the Mississippi and Warrior River systems was commandeered and $12 million was appropriated for new construction. Service was provided primarily on the Lower Mississippi.

New floating equipment was designed by prominent naval architects, and built by boat yards known for high-quality work. Modern terminal facilities were constructed to handle bulk and package freight. A special rate system was put into place to reflect the lower cost of river transportation in comparison with railroads. In spite of their innovative approach, the Railroad Administration lost money on river services and in 1920 the Federal Barge Fleet was transferred to the War Department.

The name was changed to the Inland and Coastwise Waterways Service and the experiment continued. The Waterways Service lost less money than the Railroad Administration and in 1924 was modified yet again to allow even more economical operation in a less restrictive environment. The government transferred $5 million worth of floating equipment to provide the capital stock for the new Inland Waterways Corporation.

Compression ignition or diesel engines were first used about 1910 for smaller sternwheel towboats, but did not gain ascendancy until the late 1930s, when diesel-powered propeller boats appeared. The introduction of screw propellers to the rivers came late because of their vulnerability to damage and the greater depth of water required for efficient operation. The Federal Barge Lines experiment was successful in restarting the river transportation industry.

Congress created the Inland Waterways Corporation (1924) and its Federal Barge Line. The completion of the nine-foot channel of the Ohio River in 1929 was followed by similar improvements on the Mississippi and its tributaries and the Gulf Intra-Coastal Canals. Each improvement marked a giant step by the U.S. Army Engineers (Corps of Engineers) in promoting inland waterways development. Private capital followed these improvements with heavy investments in towboats and barges. In the years before World War II, towboat power soared steadily from 600 to 1,200 to 2,400. The shift from steam to diesel engines cut crews from twenty or more on steam towboats to an average of eleven to thirteen on diesels. By 1945, fully 50 percent of the towboats were diesel; by 1955, the figure was 97 percent. Meanwhile, the paddlewheel had given way to the propeller, the single propeller to the still-popular twin propeller.

Traffic on the Mississippi system climbed from 211 million short tons to more than 330 million between 1963 and 1974. The growth in river shipping did not abate in the final quarter of the century. Traffic along the Upper Mississippi rose from 54 million tons in 1970 to 112 million tons in 2000. The change from riveted to welded barges, the creation of integrated barges, and the innovation of double-skinned barges have led to improved economy, speed, and safety. Shipping on Mississippi barges became substantially less expensive than railroad transport, but at a cost to taxpayers. Barge traffic is the most heavily subsidized form of transport in the United States. A report in 1999 revealed that fuel taxes cover only 10 percent of the annual $674 million that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spends building and operating the locks and dams of the Mississippi River. Barges figured there were a lot more corn and soybeans in Iowa than there was scrap iron! Until then, some had limited themselves to pushing scrap downstream and coal upriver, but those commodities were dwarfed by the potential downstream grain business. Overcoming the challenges of expansion, more players jumped into the booming barge industry.

Today 60% of U.S. grain exports travel by barge down the Mississippi River system to the Gulf. The barge industry handles 15% of the nation's inter-city traffic for just 3% of the nation's freight bill. Barge transportation is the safest surface mode of transportation and is more fuel efficient than rail. A single barge carries the equivalent of 15 railcars and on the Lower Mississippi some tows handle up to 40 plus barges.

Flood of 1927

The Mississippi 1927 flood began when heavy rains pounded the central basin of the Mississippi in the summer of 1926. By September, the Mississippi's tributaries in Kansas and Iowa were swollen to capacity. On New Year's Day of 1927, the Cumberland River at Nashville topped levees at 56.2 feet (17.1 m). The Mississippi River broke out of its levee system in 145 places and flooded 27,000 square miles (70,000 km2) or about 16,570,627 acres (67,058.95 km2). The area was inundated up to a depth of 30 feet (9.1 m). The flood caused over $400 million in damages and killed 246 people in seven states. The flood affected Arkansas, Illinois, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, and Tennessee. Arkansas was hardest hit, with 14% of its territory covered by floodwaters. By May 1927, the Mississippi River below Memphis, Tennessee, reached a width of 60 mi (97 km).

Mississippi River Commission

The Mississippi River Commission was established in 1879 to facilitate improvement of the Mississippi River from the Head of Passes near its mouth to its headwaters. The stated mission of the Commission was to:

- Develop and implement plans to correct, permanently locate, and deepen the channel of the Mississippi River.

- Improve and give safety and ease to the navigation thereof.

- Prevent destructive floods.

- Promote and facilitate commerce, trade, and the postal service.

For nearly a half century the MRC functioned as an executive body reporting directly to the Secretary of War. The Great Mississippi Flood of 1927 changed the mission of the MRC. The consequent Flood Control Act of 1928 created the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project (MR&T). The act assigned responsibility for developing and implementing the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project (MR&T) to the Mississippi River Commission. The MR&T project provides for:

- Control of floods of the Mississippi River from Head of Passes to vicinity of Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

- Control of floods of the tributaries and outlets of the Mississippi River as they are affected by its backwaters.

- Improvement for navigation of the Mississippi River from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to Cairo, Illinois. This includes improvements to certain harbors and improvement for navigation of Old and Atchafalaya Rivers from the Mississippi River to Morgan City, Louisiana.

- Bank stabilization of the Mississippi River from the Head of Passes to Cairo, Illinois.

- Preservation, restoration, and enhancement of environmental resources, including but not limited to measures for fish and wildlife, increased water supplies, recreation, cultural resources, and other related water resources development programs.

- Semi-annual inspection trips to observe river conditions and facilitate coordination with local interests in implementation of the project.

The President of the Mississippi River Commission is its executive head. The mission is executed through the Mississippi Valley Division, U.S. Army Engineer Districts in St. Louis, Memphis, Vicksburg, and New Orleans.

US Army Corps of Engineers

The United States Army Corps of Engineers is a federal agency and a major Army command made up of some 34,600 civilian and 650 military personnel, making it the world's largest public engineering, design and construction management agency. Although generally associated with dams, canals and flood protection in the United States, USACE is involved in a wide range of public works.

- Navigation. Supporting navigation by maintaining and improving channels was the Corps of Engineers' earliest Civil Works mission, dating to Federal laws in 1824 authorizing the Corps to improve safety on the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers and several ports. Today, the Corps maintains more than 12,000 miles (19,000 km) of inland waterways and operates 235 locks. These waterways—a system of rivers, lakes and coastal bays improved for commercial and recreational transportation—carry about 1/6 of the Nation's inter-city freight, at a cost per ton-mile about 1/2 that of rail or 1/10 that of trucks. USACE also maintains 300 commercial harbors, through which pass 2 billion tons of cargo a year, and more than 600 smaller harbors.

- Flood Damage Reduction. The Corps was first called upon to address flood problems along the Mississippi river in the mid-19th century. They began work on the Mississippi River and Tributaries Flood Control Project in 1928, and the Flood Control Act of 1936 gave the Corps the mission to provide flood protection to the entire country. Neither the Corps nor any other agency can prevent all flood damages; and when floods cause damage, there is sure to be controversy.

The Corps maintained its own fleet of river steamers, derricks, dredges and cranes, all steam powered, for many years. See Montgomery (snagboat)

The Feds Step In: the Tennessee Valley Authority Project

On May 18, 1933, Congress passed the Tennessee Valley Authority Act. Right from the start, TVA established a unique problem-solving approach to fulfilling its mission-integrated resource management. Each issue TVA faced—whether it was power production, navigation, flood control, malaria prevention, reforestation, or erosion control—was studied in its broadest context.

By the end of the war, TVA had completed a 650-mile (1,050 km) navigation channel the length of the Tennessee River and had become the nation’s largest electricity supplier. Again the TVA project needed the services of steamers to haul cement for the dams.

World War II LST construction

The Second World War put huge demands on shipping. Every floating vessel was put to work, retired or old. The Gulf Coast was turned into a huge industrial works. Shipbuilding, steel making in Alabama, forestry, and landing craft building in the Plains towns. The Prairie boats were moved down the river for re-staging in New Orleans. The Higgins boat put its mark on shipping.

The need for Landing Ships, Tank (LST), was urgent in the war, and the program enjoyed a high priority throughout the war. Since most shipbuilding activities were located in coastal yards and were largely used for construction of large, deep-draft ships, new construction facilities were established along inland waterways of the Mississippi. In some instances, heavy-industry plants such as steel fabrication yards were converted for LST construction. This posed the problem of getting the completed ships from the inland building yards in the Plains to deep water. The chief obstacles were bridges. The US Navy successfully undertook the modification of bridges and, through a "Ferry Command" of Navy crews, transported the newly constructed ships to coastal ports for fitting out. The success of these "cornfield" shipyards of the Middle West was a revelation to the long-established shipbuilders on the coasts. Their contribution to the LST building program was enormous. Of the 1,051 LSTs built during World War II, 670 were constructed by five major inland builders. The most LSTs constructed during WWII were built in Evansville, Indiana, by Missouri Valley Bridge and the International Iron & Steel Co.

The end of steamboats

The Great Depression, the explosion of shipbuilding capability on the river because of the war, and the rise of diesel tugboats finished the steamboat era. Boats were tied up as they had time expired, being built in the First World War or 1920s. Lower crew requirements of diesel tugs made continued operation of steam towboats uneconomical during the late 1940s. The wage increases caused by inflation after the war, and the availability of war surplus tugs and barges, put the older technology at a disadvantage. Some steam-powered, screw-propeller towboats were built but they were either later converted to diesel-power or retired. A few diesel sternwheelers stayed on the rivers after steam sternwheelers disappeared. Jack Kerouac noted in On the Road seeing many derelict steamers on the River at this time. Many steam vessels were broken up. Steam derricks and snagboats continued to be used until the 1960s and a few survivors soldiered on.

Today, few paddlewheelers continue to run on steam power. Those that do include the Belle of Louisville, Natchez, Minne-Ha-Ha, Chautauqua Belle, Julia Belle Swain, and American Queen. Other vessels propelled by sternwheels exist, but do not employ the use of steam engines. Overnight passage on steamboats in the United States ended in 2008. The Delta Queen could resume that service, but it requires the permission of the United States Congress. The American Queen was in the US Ready Reserve fleet and was purchased and relaunched in April 2012 and now carries passengers on 4 to 10 night voyages on the Mississippi, Ohio, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers as the flagship of the American Queen Steamboat Company.

On October 18, 2014, the Belle of Louisville became the first Mississippi River-style steamboat to reach 100 years old. To celebrate the unprecedented achievement there was a five-day festival in Louisville, KY called Belle's Big Birthday Bash.

Current Natchez

The ninth and current Natchez, the Str. Natchez, is a sternwheel steamboat based in New Orleans, Louisiana. Built in 1975, she is sometimes referred to as the Natchez IX. She is operated by the New Orleans Steamboat Company and docks at the Toulouse Street Wharf. Day trips include harbor and dinner cruises along the Mississippi River. It is modeled not after the original Natchez, but instead by the steamboats Hudson and Virginia. Its steam engines were originally built in 1925 for the steamboat Clairton, from which the steering system and paddlewheel shaft also came. From the S.S. J.D. Ayres came its copper bell, made of 250 melted silver dollars. The bell has on top a copper acorn that was once on the Avalon, now known as the Belle of Louisville, and on the Delta Queen. It also features a steam calliope, made by the Frisbee Engine Company, that has 32 notes. The wheel is made of white oak and steel, is 25 feet (7.6 m) by 25 feet (7.6 m), and weighs 26 tons.[2] The whistle came from a ship that sank in 1908 on the Monagabola River. It was launched from Braithwaite, Louisiana. It is 265 feet (81 m) long and 46 feet (14 m) wide. It has a draft of six feet and weighs 1384 tons. It is mostly made of steel, due to United States Coast Guard rules.[3] In 1982 the Natchez won the Great Steamboat Race, which is held every year on the Wednesday immediately before the first Saturday in May, as part of the Kentucky Derby Festival held in Louisville, Kentucky.[4] It has partaken in other races, and has never lost.[5] Those it has beaten include the Belle of Louisville, the Delta Queen, the Belle of Cincinnati, the American Queen, and the Mississippi Queen.

See also

References

- Hunter, Louis C. (1993). Steamboats on the Western Rivers, an Economic and Technological History. New York: Dover Publications.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Johnson, pp. 1-16

- Lloyd, James T. (1856). Lloyd's Steamboat Directory, and Disasters on the Western Waters... Philadelphia: Jasper Harding. p. 41.

In 1811, Messrs. Fulton and Livingston, having established a shipyard at Pittsburgh, for the purpose of introducing steam navigation on the western waters, built an experimental boat for this service; and this was the first steamboat that ever floated on the western rivers." "The first western steamboat was called the Orleans.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Dohan, Mary Helen (1981). Mr. Roosevelt's Steamboat, the First Steamboat to Travel the Mississippi. Dodd, Meade & Co.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dohan (1981), p. 19. An image of a model replica of the New Orleans reveals her form.

- Lloyd (1856), p. 42. "The second steamboat of the West was a diminutive vessel called the 'Comet.' Daniel D. Smith was the owner, and D. French the builder of this boat. Her machinery was on a plan for which French had obtained a patent in 1809."

- Miller, Ernest C. "Pennsylvania's Oil Industry". Pennsylvania History Studies, No. 4. Gettysburg, PA: Pennsylvania History Association: 69.

In the summer of 1813, Daniel D. Smith altered a river barge at Pittsburgh, using an engine invented by Daniel French. The craft, called the Comet, was sent down to New Orleans and also made a few trips to Natchez, but apparently was unsuccessful in the trade...

- Hunter (1993), p. 127. "The first departure from the Boulton and Watt type of engine was the French oscillating cylinder engine with which the first three steamboats built by the Brownsville group were equipped- the Comet (25 tons, 1813), the Despatch (25 tons, 1814), and the Enterprise (75 tons, 1814). The first of these was not a success, and the Despatch made no name for herself; but the Enterprise was one of the best of the early western steamboats."

- Lloyd (1856), pp. 42–43. "The Vesuvius is the next in this record. She was built by Mr. Fulton, at Pittsburgh, for a company, the several members of which resided at New York, Philadelphia, and New Orleans. She sailed under the command of Capt. Frank Ogden, for New Orleans, in the spring of 1814."

- Hunter (1993), p. 70. "The first steamboats were too heavy and required too much power and too much depth of water to be practicable on most parts of the Mississippi-Ohio River system."

- Lloyd (1856), p. 43. "The Enterprise was No. 4 of the Western steamboat series."

- Maass, Alfred R. (1996). "Daniel French and the Western Steamboat Engine". The American Neptune. 56: 29–44.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Maass (1996), p. 39. "She had a shallow draft; Latrobe, inspecting a shoal the Enterprize passed daily, wrote [to Robert Fulton on 9 August 1814] that no boat of greater than 2' 6" could pass in low water."

- American Telegraph. Brownsville, PA. July 5, 1815.

Arrived at this port on Monday last, the Steam Boat Enterprize, Shreve, of Bridgeport, from New Orleans, in ballast, having discharged her cargo at Pittsburg. She is the first steam boat that ever made the voyage to the Mouth of the Mississippi and back.

Missing or empty|title=(help) - Hunter (1993), pp. 12–13.

- Steubenville Western Herald. November 10, 1815. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Hunter (1993), p. 127. "Not only was the Washington the largest steamboat on the western rivers at the time of her construction, but she outperformed all previously built steamboats and established a high reputation for herself and for Shreve."

- Hanson, Joseph Mills. The Conquest of the Missouri: Being the Story of the Life and Exploits of Captain Grant Marsh, pp. 421-2, Murray Hill Books, New York and Toronto, 1909, 1937, 1946.

- French, Lester Gray, ed. (July 1900). "Boating on the Ohio". Machinery. Industrial Press. 6: 334.

- "History of Washington". Historic Town of Washington, LA. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- The exact number of casualties is unclear. Compare Crutchfield, James (2008). It Happened on the Mississippi River. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-762-75236-2.

- "The Riverboats Natchez". Riverboat Dave's.

- Cramer, Zadok (1817). The Navigator: Containing Directions for Navigating the Monongahela, Allegheny, Ohio, and Mississippi Rivers (9th ed.). Pittsburgh: Cramer, Spear and Eichbaum.

- Johnson, Leland R. (2011). "Harbinger of Revolution", in Full steam ahead: reflections on the impact of the first steamboat on the Ohio River, 1811-2011. Rita Kohn, editor. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-0-87195-293-6

- Maass, Alfred R. (1994). "Brownsville's Steamboat Enterprize and Pittsburgh's Supply of General Jackson's Army". Pittsburgh History. 77: 22–29. ISSN 1069-4706.

- ——— (2000). "The Right of Unrestricted Navigation on the Mississippi, 1812–1818". The American Neptune. 60: 49–59.

- Twain, Mark (1859). Life on the Mississippi.

External links