Statue of Edward Colston

The statue of Edward Colston is a bronze statue of Bristol-born merchant Edward Colston (1636–1721), which was originally erected in The Centre in Bristol, England. Created in 1895 by sculptor John Cassidy on a Portland stone plinth, it was designated a Grade II listed structure in 1977.

| Statue of Edward Colston | |

|---|---|

The statue in 2019 | |

| Artist | John Cassidy |

| Completion date | 13 November 1895 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Subject | Edward Colston |

| Condition | Figure toppled, damaged and removed; plinth defaced by demonstrators |

| Location | Bristol, England |

Listed Building – Grade II | |

| Official name | Statue of Edward Colston |

| Designated | 4 March 1977 |

| Reference no. | 1202137 |

The statue has been subject to increasing controversy since the 1990s, when Colston's prior reputation as a philanthropist came under scrutiny due to his involvement in the Atlantic slave trade. On 7 June 2020, the statue was toppled, defaced, and pushed into Bristol Harbour during the George Floyd protests related to the Black Lives Matter movement. The plinth was also covered in graffiti, but remains in place. The statue was recovered from the harbour and put into safe storage by Bristol City Council on 11 June.

Description

.jpg)

In its original state the monument consisted of an 8 ft 8 in (2.64 m) bronze statue of Colston on top of a 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) plinth.[1] The statue depicts Colston in a flowing wig, velvet coat, satin waistcoat, and knee-breeches as was typical in his day.[1] The plinth is made of Portland stone and adorned with bronze plaques and figures of dolphins. Of the four plaques—one on each face of the plinth—three are relief sculptures in an Art Nouveau style: two of these depict scenes from Colston's life and the third exhibits a maritime fantasy. The plaque on the south face bears the words "Erected by citizens of Bristol as a memorial of one of the most virtuous and wise sons of their city AD 1895" and "John Cassidy fecit" (John Cassidy made this).[2]

Background

Edward Colston

Colston was a Bristol-born merchant who made much of his fortune from the slave trade, particularly between 1680 and 1692. He was an active member of the Royal African Company, and was briefly deputy governor in 1689–90. During his tenure, the Company transported an estimated 84,000 slaves from West Africa to the Americas.[3] Colston used his wealth to provide financial support to almshouses, hospitals, schools, workhouses and churches throughout England, particularly in his home city of Bristol.[4] He represented Bristol as its Member of Parliament from 1710–13.[5] He left £71,000 to charities after his death, as well as £100,000 to members of his family.[4][6] In the 19th century he was seen as a philanthropist.[4] The fact that much of his fortune was made in the slave trade was largely ignored until the 1990s.[2]

Statue

The statue, designed by John Cassidy, was erected in the area now known as The Centre in 1895 to commemorate Colston's philanthropy.[7][8] It was proposed by James Arrowsmith, the president of the Anchor Society. Several appeals to the public and Colston-related charitable bodies, over the course of a two-year fundraising effort, raised £650, which was less than the amount needed for its casting and erection. The remaining balance, £150, was given by an anonymous donor.[9][10] Alumni of Colston's School were also invited to participate. The statue was unveiled by the mayor and the bishop of Bristol on 13 November 1895, a date which had been referred to as "Colston Day" in the city.[10] Further funds were raised after the unveiling, including a contribution from the Society of Merchant Venturers.[10]

On 4 March 1977, it was designated as a Grade II listed structure. Historic England described the statue as being "handsome" and that "the resulting contrast of styles is handled with confidence". They also note that the statue offers good group value with other memorials, including a statue of Edmund Burke, the Cenotaph, and a drinking fountain commemorating the Industrial and Fine Art Exhibition of 1893.[2]

Controversy

20th century

The statue became controversial by the end of the 20th century, as Colston's activities as a major slave trader became more widely known.[11] H. J. Wilkins, who uncovered his slave-trading activities in 1920, commented that "we cannot picture him justly except against his historical background".[12][13] Colston's involvement in the slave trade predated the abolition movement in Britain, and was during the time when "slavery was generally condoned in England—indeed, throughout Europe—by churchmen, intellectuals and the educated classes".[14] From the 1990s onwards,[15] campaigns and petitions called for the removal of the statue and described it as a disgrace.[16]

In 1992, the statue was depicted in the installation Commemoration Day by Carole Drake, as part of the Trophies of Empire exhibition at the Arnolfini, a gallery in a former tea warehouse in Bristol's harbour. Drake's installation combined a replica of the statue swinging above rotting chrysanthemums, a favourite flower of Colston, in front of a projected photograph of schoolgirls at Colston School covering his statue with flowers in 1973 and the audio of the school hymn "Rejoice ye pure in heart".[17][18] In the 1994 catalogue of Trophies of Empire, Drake stated the work refers to:[19]

...the blind spots in Western culture, a collective amnesia which denies the sources of wealth which built such 'trophies of empire', and the ways in which dominant white culture and its people benefit from the exploitation of other cultures and people both overseas and at home.

In January 1998, "SLAVE TRADER" was written in paint on the base of the statue. Bristol City councillor Ray Sefia said: "If we in this city want to glorify the slave trade, then the statue should stay. If not, the statue should be marked with a plaque that he was a slave trader or taken down."[15][20][21]

21st century

In a 2014 poll in the local newspaper, the Bristol Post, 56% of the 1,100 respondents said it should stay while 44% wanted it to go.[22] Others called for a memorial plaque honouring the victims of slavery to be fitted to his statue. Bristol's first elected mayor, George Ferguson, stated on Twitter in 2013 that "Celebrations for Colston are perverse, not something I shall be taking part in!"[23] In August 2017 an unauthorized commemorative plaque by sculptor Will Coles was affixed to the statue's plinth, which declared that Bristol was the "Capital of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1730-1745" and memorialising "the 12,000,000 enslaved of whom 6,000,000 died as captives". Cole stated that his aim was "to try to get people to think".[24] The plaque was removed by Bristol City Council in October of the same year.[25] In 2018, Thangam Debbonaire, Labour MP for Bristol West, wrote to Bristol City Council calling for the removal of the statue.[16][26] A petition to remove the statue had garnered more than 11,000 signatures.[27]

An unofficial art installation appeared in front of the statue on 18 October 2018 to mark Anti-Slavery Day in the UK. It depicted about a hundred supine figures arranged as on a slave ship, lying as if they were cargo, surrounded by a border listing jobs typically done by modern-day slaves such as 'fruit picker' and 'nail bar worker'; it remained for some months.[28][29] The labels around the bow of the ship said 'here and now'.[30] Another artistic intervention saw a ball and chain attached to the statue.[31]

Rewording the plaque

In July 2018, Bristol City Council, which was responsible for the statue, made a planning application to add a second plaque which would "add to the public knowledge about Colston" including his philanthropy and his involvement in slave trading, though the initial wording suggested came in for significant criticism and re-wording took place.[32][33]

The initial wording of the second plaque mentioned Colston's role in the slave trade, brief tenure as a Tory MP for Bristol, and criticised his philanthropy as religiously selective:

As a high official of the Royal African Company from 1680 to 1692, Edward Colston played an active role in the enslavement of over 84,000 Africans (including 12,000 children) of whom over 19,000 died en route to the Caribbean and America. Colston also invested in the Spanish slave trade and in slave-produced sugar. As Tory MP for Bristol (1710-1713), he defended the city's 'right' to trade in enslaved Africans. Bristolians who did not subscribe to his religious and political beliefs were not permitted to benefit from his charities.[34]

The Society of Merchant Venturers, an organisation of which Colston was a member, objected to the wording and a Bristol Conservative councillor called it "revisionist" and "historically illiterate".[32]

A second version, co-written by an associate professor of history at the University of Bristol, was proposed by the council in 2018, giving a brief description of Colston's philanthropy, role in the slave trade, and time as an MP, while noting that he was now considered controversial. This wording was edited by a former curator at the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, creating a third proposal that was backed by the Bristol Civic Society.[33] However, it was criticised by Madge Dresser, the historian behind the second proposal, as a "sanitised" version of history, arguing the wording minimised Colston's role, omitted the number of child slaves, and focused on West Africans as the original enslavers. The third version was reported to have been written by a member of the Society of Merchant Venturers.[33] A bronze plaque was cast with the following:

Edward Colston (1636–1721), MP for Bristol (1710–1713), was one of this city's greatest benefactors. He supported and endowed schools, almshouses, hospitals and churches in Bristol, London and elsewhere. Many of his charitable foundations continue. This statue was erected in 1895 to commemorate his philanthropy. A significant proportion of Colston's wealth came from investments in slave trading, sugar and other slave-produced goods. As an official of the Royal African Company from 1680 to 1692, he was also involved in the transportation of approximately 84,000 enslaved African men, women and young children, of whom 19,000 died on voyages from West Africa to the Caribbean and the Americas.

However, after the plaque was cast, its installation was vetoed in March 2019 by Bristol's mayor, Marvin Rees, who criticised the Society of Merchant Venturers for the phrasing. A statement from the mayor's office called it "unacceptable", claimed that Rees had not been consulted, and promised to continue work on a second plaque.[35] In June 2020 the Society of Merchant Venturers stated it was "inappropriate" for the society to have become involved in the rewording of the plaque in 2018.[36]

Toppling and removal

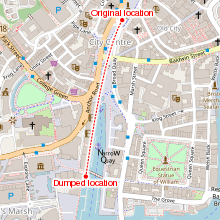

On 7 June 2020, during the global protests following the killing of George Floyd in the United States,[37] the statue was pulled down by demonstrators who then jumped on it.[27] They daubed it in red and blue paint, and one protester placed his knee on the statue's neck to allude to Floyd's death under a knee of a white policeman.[37][38] The statue was then rolled down Anchor Road and pushed into Bristol Harbour.[27][39][40]

Superintendent Andy Bennett of Avon and Somerset Police stated that they had made a "tactical decision" not to intervene and had allowed the statue to be toppled, citing a concern that stopping the act could have led to further violence and a riot.[27][41] They also stated that the act was criminal damage and confirmed that there would be an investigation to identify those involved, adding that they were in the process of collating footage of the incident.[42][43]

Reaction

On 7 June, the Home Secretary, Priti Patel, called the toppling "utterly disgraceful", "completely unacceptable", and "sheer vandalism". She added, "it speaks to the acts of public disorder that have become a distraction from the cause people are protesting about."[44][45] The Mayor of Bristol Marvin Rees said those comments showed an "absolute lack of understanding".[46]

On 8 June Rees said that the statue was an affront, and he felt no "sense of loss [at its removal]," but that the statue would be retrieved and it was "highly likely that the Colston statue will end up in one of our museums."[47] The historian and television presenter David Olusoga commented that the statue should have been taken down earlier, saying: "Statues are about saying 'this was a great man who did great things'. That is not true, he [Colston] was a slave trader and a murderer."[39]

Police Superintendent Andy Bennett also stated he understood that Colston was "a historical figure that's caused the black community quite a lot of angst over the last couple of years", adding: "Whilst I am disappointed that people would damage one of our statues, I do understand why it's happened, it's very symbolic."[27]

Rees made a statement suggesting that "it's important to listen to those who found the statue to represent an affront to humanity and make the legacy of today about the future of our city, tackling racism and inequality. I call on everyone to challenge racism and inequality in every corner of our city and wherever we see it."[48] In an interview with Krishnan Guru-Murthy, he said, "We have a statue of someone who made their money by throwing our people into water ... and now he's on the bottom of the water."[49] In a separate interview, Rees commented that the statue would probably be retrieved from the harbour "at some point", and could end up in a city museum.[46] Rees confirmed that placards left by protesters will be put on display at the M Shed museum in Bristol.[50]

A spokesperson for Boris Johnson, the Prime Minister, said that he "absolutely understands the strength of feeling" but insisted that the democratic process should have been followed, and that police should hold responsible those involved in the criminal act.[46][51][52]

Labour leader Keir Starmer said while the manner in which the statue had been pulled down was "completely wrong", it should have been removed "a long, long time ago". He added "you can't, in 21st Century Britain, have a slaver on a statue. That statue should have been brought down properly, with consent, and put in a museum."[46][53]

The Society of Merchant Venturers, in a statement on 12 June, said that "the fact that it [the statue] has gone is right for Bristol. To build a city where racism and inequality no longer exist, we must start by acknowledging Bristol's dark past and removing statues, portraits and names that memorialise a man who benefitted from trading in human lives."[36]

Retrieval and storage

At 5 am on 11 June 2020, the statue was retrieved from Bristol harbour by Bristol City Council, who plan to clean it to prevent corrosion before exhibiting it in a museum without removing the graffiti and ropes placed on it by the protesters.[54][55] Whilst cleaning mud from the statue, M Shed discovered an 1895 issue of Tit-Bits magazine containing a handwritten date, 26 October 1895, and the names of those who originally fitted the statue.[56][57][58]

Police investigation

The day after the toppling, the police announced that they identified 17 people in connection with the incident, but had not yet made any arrests.[59] On 22 June 2020 the police released images of people connected to the incident, and asked the public for help identifying the individuals.[60] On 1 July, a 24-year-old man was arrested on suspicion of criminal damage to the statue.[61]

Subsequent events

After the toppling of Colston's statue, a similar monument to Robert Milligan, the slave factor who was largely responsible for the construction of the West India Docks, was removed peacefully after opposition in east London by the Tower Hamlets council on 9 June 2020.[62][63] On the same day, the Mayor of London Sadiq Khan called for London statues and street names with links to slavery to be removed or renamed. Khan set up the Commission for Diversity in the Public Realm to review London's landmarks.[64]

After the statue was removed, a petition began to have a statue of Paul Stephenson erected in its place.[65] The former Bristol youth worker is a black man who was instrumental in the 1963 Bristol Bus Boycott, inspired by the US Montgomery bus boycott, which brought an end to a then-legal employment colour ban in Bristol bus companies.[66]

In what a local councillor believed was retaliation, the headstone and footstone for the enslaved man Scipio Africanus were vandalised in the churchyard of St Mary's Church, Henbury, on 17 June. The attacker broke one of the stones in two and scrawled a warning to "put Colston's statue back or things will really heat up."[67]

In the early morning of 15 July 2020, a statue by Marc Quinn was added to the empty plinth, without permission of the authorities. The statue, entitled A Surge of Power (Jen Reid) 2020 depicts a Black Lives Matter protester with a raised fist.[68][69] Quinn described it as a "new temporary, public installation".[70] Bristol City Council removed the statue on the morning of 16 July, and said it would be held in their museum "for the artist to collect or donate to our collection".[71]

See also

References

- "Colston's Day at Bristol". The Times. London. 14 November 1895. p. 10.

- Historic England. "Statue of Edward Colston (1202137)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "COLSTON, Edward II (1636–1721), of Mortlake, Surr". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Morgan, Kenneth (September 2004). "Colston, Edward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 17 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "BBC - History - British History in depth: The Business of Enslavement". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Parkes, Pamela (8 June 2020). "The city divided by a slave trader's legacy". BBC News. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Edward Colston". PMSA National Recording Project. Archived from the original on 9 January 2010. Retrieved 9 May 2007.

- Saner, Emine (29 April 2017). "Renamed and shamed: taking on Britain's slave-trade past, from Colston Hall to Penny Lane". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 24 May 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Latimer, John (1901). The Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century. p. 46.

- Ball, Roger (14 October 2019). "Myths within myths…Edward Colston and that statue". Bristol Radical History Group. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Foyle, Andrew (2004). Bristol-Pevsner Architectural Guides. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. p. 125. ISBN 0-300-10442-1.

- Wilkins, H. J. (1920). Edward Colston (1636–1721 A.D.), a chronological account of his life and work. Bristol: J. W. Arrowsmith.

- Ball, Roger. "Edward Colston Research Paper #2". Bristol Radical History Group. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Morgan, Kenneth (1999). Edward Colston and Bristol. Bristol: Bristol Branch of the Historical Association. p. 18.

- Hochschild, Adam (2006). Bury the Chains. New York City: Mariner Books. p. 15.

- Grubb, Sophie (5 June 2020). "'It's a disgrace' – Thousands call for removal of controversial Bristol statue". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020.

- Gee, Gabriel N.; Vogelaar, Alison (4 July 2018). Changing Representations of Nature and the City: The 1960s-1970s and their Legacies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96840-4.

- "Trophies of Empire | Exhibition guide relating to an exhibition, 1992". diaspora-artists.net. 1992. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Trophies of Empire. Bluecoat Gallery and Liverpool John Moores University School of Design & Visual Arts in collaboration with Arnolfini and Hull Time Based Arts. 1994. ISBN 978-0-907738-38-1.

- Wilkins, Emma (29 January 1998). "Graffiti attack revives Bristol slavery row". The Times. p. 11.

- Dresser, Madge (2009). "Remembering Slavery and Abolition in Bristol". Slavery & Abolition. 30 (2): 223–246. doi:10.1080/01440390902818955. ISSN 0144-039X. S2CID 145478877.

- Gallagher, Paul (22 June 2014). "Bristol torn apart over statue of Edward Colston: But is this a figure of shame or a necessary monument to the history of slavery?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Koch, Emily (30 August 2013). "Bristol mayor: City's celebration of Edward Colston is perverse". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 4 September 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- Pipe, Ellie (24 August 2017). "Revealed: mystery sculptor behind plaque that brands Bristol a slavery capital". Bristol24-7. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- Davis, Krishan (27 October 2017). "Unofficial plaque calling Bristol 'capital of Atlantic slave trade' removed from Edward Colston statue". Bristol Post. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "MP calls for slave trader statue removal". BBC News. 11 October 2018. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Siddique, Haroon (7 June 2020). "BLM protesters topple statue of Bristol slave trader Edward Colston". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Cork, Tristan (18 October 2018). "100 human figures placed in front of Colston statue in city centre". Bristol Live. Local World. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Anti Slavery Art Installation by Colston Statue in Bristol • Inspiring City". Inspiring City. 22 October 2018. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- Gould, Rebecca Ruth (12 June 2020). "Bringing Colston Down". London Review of Books (blog).

- Yong, Michael. "Ball and chain attached to Edward Colston's statue in Bristol city centre". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Cork, Tristan (23 July 2018). "Theft of second Colston plaque 'may be justified' says councillor". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Cork, Tristan (23 August 2018). "Row breaks out as Merchant Venturer accused of 'sanitising' Edward Colston's involvement in slave trade". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Cork, Tristan (22 July 2018). "The wording of second plaque proposed for Edward Colston statue linking him to 20,000 deaths". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2020.

- Cork, Tristan (25 March 2019). "Second Colston statue plaque not axed but mayor orders re-write". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- "Statement from the Society of Merchant Venturers". merchantventurers.com. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Protesters in England topple statue of slave trader Edward Colston into harbor". CBS News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Zaks, Dmitry (8 June 2020). "UK slave trader's statue toppled in anti-racism protests". The Jakarta Post. Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "George Floyd death: Protesters tear down slave trader statue". BBC News. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Sullivan, Rory (7 June 2020). "Black Lives Matter protesters pull down statue of 17th century UK slave trader". The Independent. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Evans, Martin (8 June 2020). "Intervening to prevent toppling of Colston statue could have sparked a riot, says Chief Constable". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Avon and Somerset Police [@ASPolice] (7 June 2020). "Statement from Bristol Area Commander Superintendent Andy Bennett following Black Lives Matter demonstration in Bristol" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- Max Foster; Nada Bashir; Rob Picheta; Susannah Cullinane. "UK protesters topple slave trader statue". CNN. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Priti Patel: Toppling Edward Colston statue 'utterly disgraceful'". Sky News. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Black Lives Matter protesters in Bristol pull down and throw statue of 17th-century slave trader into river". The Independent. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Edward Colston: Bristol slave trader statue 'was an affront'". BBC News. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- King, Jasper (8 June 2020). "Edward Colston statue: Mayor gives update on statue's future". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Grimshaw, Emma (7 June 2020). "Mayor Marvin Rees issues statement on the Black Lives Matter protest and the toppling of Colston's statue". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Guru-Murthy, Krishnan (7 June 2020). ""We have a statue of someone who made their money by throwing our people into water...and now he's on the bottom of the water." – Marvin Rees, elected Mayor of Bristol". Channel 4 News. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- "Black Lives Matter: the world responds after Bristol protesters tear down statue of slave trader Edward Colston". ITV News. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020.

- Neilan, Cat (8 June 2020). "Politics latest news: Prime Minister 'absolutely understands strength of feeling' but toppling statue still criminal act". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "George Floyd: Boris Johnson urges peaceful struggle against racism". BBC News. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Walker, Peter (8 June 2020). "Keir Starmer: pulling down Edward Colston statue was wrong". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Edward Colston statue pulled out of Bristol Harbour". BBC News. 11 June 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- "Images released as part of Colston statue investigation". Avon and Somerset Police. 21 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- M Shed [@mshedbristol] (11 June 2020). "We ended up with two surprise additions. Firstly a bicycle tyre which emerged from the harbour with the statue, and then the discovery of a clue to the people who first installed it in Bristol: A 1895 magazine rolled up inside the coat tails" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- M Shed [@mshedbristol] (11 June 2020). "After careful cleaning and drying we found someone had handwritten the names of those who originally fitted the statue and the date on the inside pages" (Tweet). Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 12 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- Brewis, Harriet (12 June 2020). "125-year-old magazine found hidden inside toppled Colston statue". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Johnson urges peaceful struggle against racism". BBC News. 8 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Appeal to identify Colston statue protesters". BBC News. 22 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Edward Colston statue: Man held over criminal damage". BBC News. 1 July 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- Mason, Rowena; Pidd, Helen (9 June 2020). "Labour councils launch slavery statue review as another is removed". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Robert Milligan: Slave trader statue removed from outside London museum". BBC News. 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- "London statues with slavery links 'should be taken down'". BBC News. 9 June 2020. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- Ross, Alex (7 June 2020). "Petition calls for statue of Bristol civil rights activist Paul Stephenson to be erected in Colston's place". Bristol Live. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Webb, Elizabeth (7 October 2019). "The Bristol Bus Boycott of 1963". Black History 365. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- "Enslaved African man's headstone vandalised". BBC News. 18 June 2020.

- "Edward Colston statue replaced by sculpture of Black Lives Matter protester". BBC News. 15 July 2020. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- Bland, Archie (15 July 2020). "Edward Colston statue replaced by sculpture of Black Lives Matter protester". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "A joint statement from Marc Quinn and Jen Reid". Marc Quinn. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- "Black Lives Matter protester statue removed". 16 July 2020. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 16 July 2020 – via www.bbc.co.uk.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Statue of Edward Colston, Bristol. |

- Hulme, Charlie; Nicolson, Lis. "Edward Colston statue, Bristol (1895)". John Cassidy: Manchester sculptor. Includes period photographs.