St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst

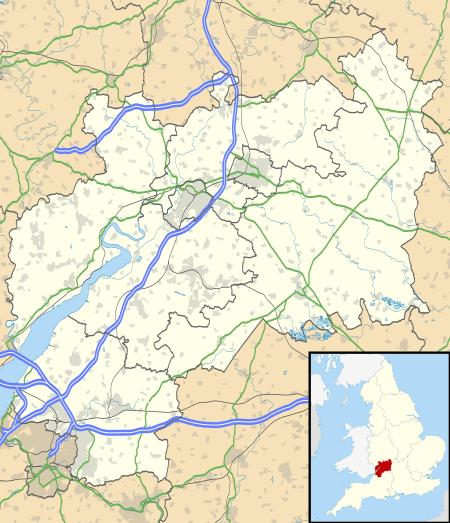

St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst, is the Church of England parish church of Deerhurst, Gloucestershire, England. Much of the church is Anglo-Saxon. It was built in the 8th century, when Deerhurst was part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Mercia. It is contemporary with the Carolingian Renaissance on mainland Europe, which may have influenced it.

| Priory church of St Mary, Deerhurst | |

|---|---|

The church seen from the southwest | |

Priory church of St Mary, Deerhurst | |

| OS grid reference | SO87032995 |

| Location | Deerhurst, Gloucestershire |

| Country | England, UK |

| Denomination | Church of England |

| Previous denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Website | Welcome to the parishes of Severnside and Twyning |

| History | |

| Status | parish church |

| Dedication | St Mary |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade I listed |

| Designated | 4 July 1960 |

| Style | Anglo-Saxon, Early English, Decorated Gothic, Perpendicular Gothic |

| Years built | 8th, 9th, 10th, 13th centuries |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | rubble masonry |

| Bells | 6 |

| Tenor bell weight | 10 long tons 3 cwt 22 qr (23,350 lb or 10.59 t) |

| Administration | |

| Deanery | Tewkesbury |

| Archdeaconry | Cheltenham |

| Diocese | Diocese of Gloucester |

| Province | Canterbury |

The church was restored and altered in the 10th century after the Viking invasion of England. It was enlarged early in the 13th century and altered in the 14th and 15th centuries. The church has been described as "an Anglo-Saxon monument of the first order".[1] It is a Grade I listed building.[2]

From the Anglo-Saxon era until the Dissolution of the Monasteries St Mary's was the church of a Benedictine priory.

Deerhurst has a second Anglo-Saxon place of worship, the 11th-century Odda's Chapel, about 200 yards southwest of the church.

Priory

By AD 804 St Mary's was part of a Benedictine monastery at Deerhurst. In about 1060 King Edward the Confessor (reigned 1042–66) granted the monastery to the Abbey of St Denis in France,[3] making it an alien priory.

According to the chronicler Matthew Paris (circa 1200–1259), in 1250 Richard, 1st Earl of Cornwall stayed at St Denis and bought Deerhurst Priory from the abbot. He took over the priory, dispersed the monks and planned to build a castle at Deerhurst on the bank of the River Severn. However, the purchase was reversed and by 1264 St Denis abbey again possessed the priory.[3]

In the 14th century England and France were at war. King Edward III seized alien priories in England in 1337, so that their incomes went to him instead of their mother houses in France. In 1345 the Crown leased Deerhurst priory to a Thomas de Bradeston for £110 a year. In 1389 the priory was let for £200 a year to a Sir John Russell and a chaplain called William Hitchcock.[3]

By 1400 King Henry IV had restored the priory to the Abbey of St Denis. But King Henry VI seized the priory in 1443, and four years later granted it to the recently-founded Eton College in Buckinghamshire.[3]

In 1461 Edward of York deposed the Lancastrian Henry VI and was crowned King Edward IV. He granted Deerhurst priory to William Buckland, a monk of Westminster Abbey. But Edward revoked the grant in 1467, claiming that Buckland had appointed only one secular chaplain, had withdrawn hospitality and had wasted the revenues of the priory.[3]

The King granted the priory to Tewkesbury Abbey instead, on condition that the abbot maintain a prior and four monks at Deerhurst. In 1467 the priory held the manors of Deerhurst, Coln St. Dennis, Compton, Hawe, Preston-on-Stour, Uckington, Welford-on-Avon and Wolston in Gloucestershire, Taynton with La More in Oxfordshire, and the rectories of Deerhurst and Uckington.[3]

Tewkesbury Abbey and its priories were suppressed in the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Deerhurst Priory and all of its estates were surrendered to the Crown on 9 January 1540.[3]

Architecture

.jpg)

Anglo-Saxon

The earliest parts of St Mary's church are the nave and chancel, which were built in the 8th century. The nave is narrow and tall: an Anglo-Saxon style seen also at Escomb, Jarrow and Monkwearmouth in County Durham.[4] The chancel was a polygonal apse and is now ruined.[5][6]

The first addition to the church was probably the west porch, which was originally of two storeys. It is longer east-west than it is north-south, and is divided into two chambers.[5] Its walls include much herringbone masonry.

Then the first pair of rectangular two-storey porticus were added, either side of the east end of the nave. A second pair of porticus, west of the first, was added later. The second floor of the porch has two doorways, each with a semicircular arch. One is at the western end on the outside of the church. Over its arch are a square hood-mould with an animal's head above. This may have led to an outside gallery. The other is at the eastern end facing into the nave. It may have led to a gallery in the nave.[7]

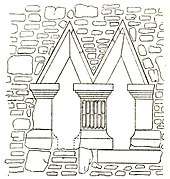

Next the west porch was raised by the addition of a third storey, and the porticus side chapels were extended westward, parallel with the nave. On the third floor of the tower, on the east side, is a double triangular-headed opening into the nave with stylised capitals and fluted pilasters with reeded decoration.

Below, at first floor level, is a blocked doorway, sited off-centre, which most likely led to a gallery in the nave. Corbels just below this doorway tend to support this supposition. There is a triangular window in the east wall of the tower and each of the nave side walls at this level.

All these phases of development were completed before the Viking invasion.[5]

John Leland (circa 1503–1552) claimed that the Vikings burnt Deerhurst. After the invasion, the church was restored in or before AD 970.[3] A fourth storey was added to the west porch, making it a tower.[5] The upper stages of the tower have quoins, but not in the Anglo-Saxon long-and-short style.[5] At the same time the present large chancel arch was inserted and the chancel may have been rebuilt.[4]

Gothic

Around AD 1200 the separate porticus were knocked through and extended westward as north and south aisles, running the length of the nave and partly overlapping the west tower. The north aisle seems to have been built first, with the south being added very slightly later. For each aisle a fine three-bay Early English arcade with moulded arches was inserted in the nave wall.[4] At an unknown date the apsidal chancel was demolished and the chancel arch walled up.

Above each arcade, windows were inserted in the north and south walls of the nave to create a clerestory. But the current aisle and clerestory windows are later: Decorated Gothic and late Perpendicular Gothic.[4]

The west window of the south aisle includes some panels of Medieval stained glass. One is from about 1300–40 and is a representation of St Catherine of Alexandria. Next to it is a larger panel from about 1450 which is a representation of St Alphege (circa AD 953–1012).[8] Alphege started his religious life by entering Deerhurst monastery as a boy.

Gothic Revival

William Wailes made the stained glass in the west window of the north aisle in 1853. Clayton and Bell made the stained glass in one of the north windows of the north aisle in 1861. The pulpit was also made in 1861.[8] It was designed by the architect William Slater, who directed a restoration of the church in 1861–63.[4]

Role of the west tower

Possible first floor chapel

The first floor of the west tower may have had the same role as that in the westwork of a Carolingian church. Westworks had an altar on the first floor, to which access was by flanking staircase towers. South of the tower is a later Mediæval spiral staircase that used to lead to the second floor of the tower. The original staircase may have been within the tower.[9][10]

The twin staircase tower arrangement was included only in the larger Anglo-Saxon churches in England (e.g. possibly Winchester and Canterbury), which have now been lost. Deerhurst may have housed an altar similarly to the Carolingian arrangement, which would account for the position of the door to the side and the triangular window, if the altar was at the centre.[11]

Bells

The Regularis Concordia, written about AD 973 as part of the English Benedictine Reform, includes instructions on how bells should be rung for the Mass and holidays.[12] This is about the time that the height of St Mary's west tower was increased to create the present belfry. But no Anglo-Saxon bells survive at Deerhurst.

The tower has a ring of six bells. Abel Rudhall of Gloucester cast the second and fourth bells in 1736 and the tenor bell in 1737. Thomas Rudhall cast the third bell in 1771. Thomas II Mears of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry cast the fifth bell in 1826. John Taylor & Co of Loughborough, Leicestershire cast the treble bell in 1882.[13]

Sculpture

Entrance to the church is through the west porch, which now forms the lower stages of the west tower. The present west doorway is not the original, but an animal's head above it remains. Animal head label-stops with spiral decoration have been moved from outside to the inner doorway. Others form the label-stops of the chancel arch at the end of the nave. There are similar Anglo-Saxon animal heads in the parish churches of Alkborough in Lincolnshire and Barnack in the Soke of Peterborough.[5]

Inside the porch, on the ground floor over the inner doorway, is an 8th-century relief of the Virgin and Child. On the ruined apse is a 10th-century relief of an angel, showing Byzantine influence.[4]

In the north aisle is the baptismal font, which is one of the oldest in England. The bowl and upper part of the stem are cylindrical. The lower part of the stem is octagonal and plain, as if it were meant to slot into the floor. The bowl is decorated with a broad band of double trumpet-spirals, with narrower bands of vine scrolls above and below.[4]

This is the only known example of a double spiral pattern on a font. However, similar decoration is found on 9th-century English manuscripts and on a pendant found in the Trewhiddle Hoard in Cornwall. On this basis Sir Alfred Clapham (1885–1950) dated the font to the 9th century.[4]

Monuments

In the church is a double monumental brass to Sir John Cassey and his wife (circa 1400). Cassey was Chancellor of the Exchequer to King Richard II. In the chancel are early 16th-century brasses of two ladies.[8] A plaque commemorates the composer George Butterworth, MC (1885–1916).[14]

Burials

In the churchyard are war graves of two First World War soldiers:[16] Pte Lewis Cox, RAMC, who died in 1917[17] and Pte George Chalk, RASC, who died in 1919.[18]

- Elizabeth Brugge (daughter of Thomas Brugge, 5th Baron Chandos

References

- Verey 1970, p. 16.

- Historic England. "The Church of St Mary (Grade I) (1151998)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- Page 1907, pp. 103–105.

- Verey 1970, p. 168.

- Verey 1970, p. 167.

- Blair 1977, p. 186.

- Blair 1977, p. 189.

- Verey 1970, p. 169.

- "Deerhurst Priory, Gloucestershire". UK SouthWest. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Bagshaw, Steve; Bryant, Richard; Hare, Michael (2008). "The Discovery of an Anglo-Saxon Painted Figure at St Mary's Church, Deerhurst, Gloucestershire". The Antiquaries Journal. 86: 66–109. doi:10.1017/S0003581500000068.

- "Deerhurst". Great English Churches. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Blair 1977, p. 187.

- Baldwin, John (13 May 2013). "Deerhurst S Mary". Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers. Central Council for Church Bell Ringers. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "George S. Kaye Butterworth, Hugh Montagu Butterworth". War Memorials Online. Retrieved 28 October 2019.

- Kneen, Maggie (2015). "Ninth-century Deerhurst: An Exploation of Colour" (PDF). Glevensis. 48: 18–29.

- "Deerhurst (St. Mary) Churchyard". CWGC. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- "Cox, Lewis Alfred". CWGC. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- "Chalk, George". CWGC. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

Bibliography

- Bailey, RN (2005). Anglo-Saxon Sculptures at Deerhurst. Bristol: Friends of Deerhurst Church. ISBN 978-0952119999.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Blair, Peter Hunter (1977) [1956]. An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England (2nd ed.). Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. pp. 185–189. ISBN 0-521-29219-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Conant, KJ (1992) [1959]. Carolingian and Romanesque Architecture 800–1200 (4th ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0140560138.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Elrington, CR, ed. (1968). "Deerhurst". A History of the County of Gloucester. Victoria County History. VIII. London: Oxford University Press for the Institute of Historical Research. pp. 34–49. ISBN 978-0197227244.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fernie, Eric (1983). The Architecture of the Anglo-Saxons. London: BT Batsford. ISBN 978-0713415827.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Page, William, ed. (1907). "The Priory of Deerhurst". A History of the County of Gloucester. Victoria County History. II. Westminster: Archibald Constable & Co. pp. 103–105. ISBN 978-0712905558.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Taylor, HM; Taylor, J (1965–1978). Anglo-Saxon Architecture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521216920.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Verey, David (1970). Gloucestershire: The Vale and the Forest of Dean. The Buildings of England. 2. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 16, 166–169.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St Mary's Priory Church, Deerhurst. |