St John the Baptist's Church, Atherton

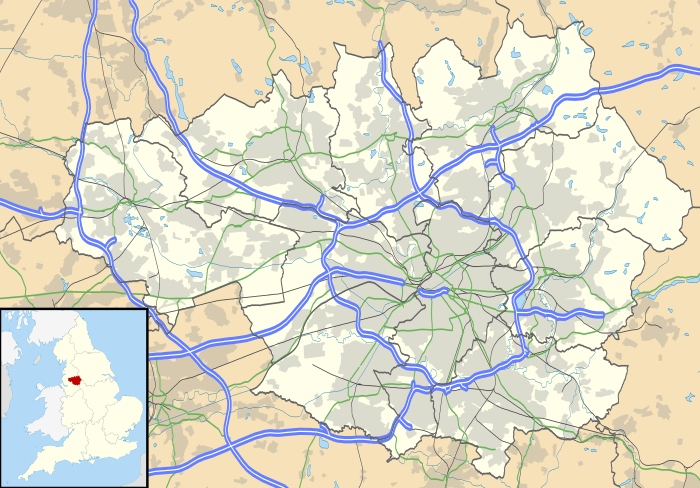

St John the Baptist's Church is in Market Place, Atherton, Greater Manchester, England. It is an active Anglican parish church in the Leigh deanery in the archdeaconry of Salford, and diocese of Manchester.[1] Together with St George's and St Philip's Churches in Atherton and St Michael and All Angels at Howe Bridge, the church is part of the United Benefice of Atherton and Hindsford with Howe Bridge.[2] It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade II listed building.[3]

| St John the Baptist's Church, Atherton | |

|---|---|

| The Parish Church of St John the Baptist, Atherton | |

Tower of St John the Baptist's Church, Atherton | |

St John the Baptist's Church, Atherton Location in Greater Manchester | |

| OS grid reference | SD 676,031 |

| Location | Market Place, Atherton, Greater Manchester |

| Country | England |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Website | Atherton Parish Church |

| History | |

| Status | Parish Church |

| Founded | 1645 |

| Dedication | St John the Baptist |

| Consecrated | 1879 (present church) |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Active |

| Heritage designation | Grade II |

| Designated | 15 July 1966 |

| Architect(s) | Paley and Austin Paley, Austin and Paley |

| Architectural type | Church |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1878 |

| Completed | 1896 |

| Construction cost | £10,000 (first phase) |

| Specifications | |

| Materials | Stone, tiled roofs |

| Administration | |

| Parish | Atherton and Hindsford |

| Deanery | Leigh |

| Archdeaconry | Salford |

| Diocese | Manchester |

| Province | York |

| Clergy | |

| Rector | Revd Kathryn Carmyllie |

History

There have been three chapels or churches on the site of St John the Baptist parish church. The first chapel at Chowbent was built in 1645 by John Atherton as a chapel of ease of Leigh Parish Church. It was sometimes referred to as the Old Bent Chapel.[4] It was not consecrated and used by the Presbyterians as well as the Vicar of Leigh. In 1721 Lord of the manor Richard Atherton expelled the dissenters who subsequently built Chowbent Chapel. The first chapel was consecrated in 1723 by the Bishop of Sodor and Man.[5]

The first chapel was replaced by a new St John's Chapel on the same site which was consecrated by the Bishop of Chester in 1814.[5] It was in turn replaced by the present church, designed by the Lancaster architects Paley and Austin. It was built in two phases. The chancel and first three bays of the nave were built in 1878–79,[6] and consecrated in 1879.[5] The cost was £10,000 (equivalent to £1,020,000 in 2019),[7] of which £3,200 was given by the colliery owners Fletcher, Burrows and Company.[8] The west end, which included a modified version of the southwest tower 120 feet (37 m) high, was completed between 1890 and 1896 by the successors in the Lancaster practice, Paley, Austin and Paley.[9]

From 1899 the church was affected by mining subsidence, causing the tower to separate from the south aisle. The tower has been stabilised, but remains out of alignment and is leaning. In 1991 the east end of the church was badly damaged by fire. It was repaired and re-ordered by Peter Skinner in 1996–97;[10] the re-ordering included dividing the chancel from the rest of the church to create a church hall.[10][11]

Architecture

Exterior

The church is constructed in Runcorn sandstone with ashlar dressings and a tiled roof.[12] Its architectural style is that of the late Decorated period. The plan consists of a five-bay nave with a clerestory, north and south aisles, a two-bay chancel with a north chapel and a south two-storey vestry and organ chamber, and a southwest tower. The tower is in five stages with octagonal buttresses at each corner, which rise above the parapet to form turrets with conical caps. The parapet is embattled.[10] The doorway is on the south side of the tower, and above it is a four-light window. There are clock faces in the fourth stage, and the bell openings in the top stage have four lights. Above each bell opening is a statue in a canopied niche. On the south side of the church the windows have four lights, while those on the north side have three lights.[3] Along the clerestory are square windows, two to a bay, which contain two different types of tracery.[10][11] To the east of the vestry and organ chamber is an octagonal turret.[3] The west and east windows are large, the west window having seven lights, and the east window six.[10] Under the east window is red and buff chequerwork carved with roses, the IHC christogram, leaves and swords.[11] The hour-chiming clock was installed by Potts of Leeds in 1895.[13]

Interior

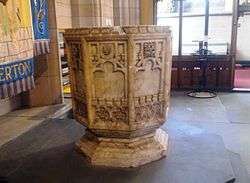

The interior is in Stourton stone with a Yorkshire stone floor. The nave has a hammerbeam roof. The arcades are carried on clustered piers. The former intricately carved chancel screen now acts as a reredos behind the altar at the east end of the nave. The stone pulpit, which contains marble panels with niches depicting scenes from the life of Christ in semi-relief, is a memorial to the Rt Revd James Fraser, Bishop of Manchester, who died in 1885. The octagonal font is in alabaster and is decorated with panels. Box pews, one of which is dated 1728, have been re-used as dado panelling in the vestry. In the nave are lamps designed by Peter Skinner. The stained glass in the east window, dated 1896, is by C. E. Kempe, and a window in the south aisle contains glass by Ward and Hughes dating from 1895. In another south aisle window is glass from 1922 by Edward Moore, which has been moved from the north chapel. The rest of the windows have been re-glazed after the 1991 fire with clear glass.[10] The two-manual pipe organ was built in 1967 by Hill, Norman and Beard,[14] replacing an earlier three-manual organ of 1888 by J. C. Bishop and Son.[15]

Appraisal

The church was designated as a Grade II listed building on 15 July 1966.[3] Grade II is the lowest of the three gradings given by English Heritage, and includes buildings that "are nationally important and of special interest".[16] The description in the National Heritage List for England states that it is "an imposing building which exhibits fine craftsmanship both inside and out".[3] The authors of the Buildings of England series describe the church as "monumental, one of Paley & Austin's best", and state that the tower is "magnificently monumental".[10] Brandwood et al. in their book on the architectural practice of Sharpe, Paley and Austin agree that it is "one of Paley & Austin's finest churches".[17]

See also

References

Citations

- Leigh Deanery, anglican.org, archived from the original on 17 August 2009, retrieved 17 February 2013

- The United Benefice of Atherton and Hindsford with Howe Bridge, Atherton Parish, retrieved 17 February 2013

- Historic England, "Church of St John, Wigan (1068475)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Wright (1921), p. 37

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, J. (editors) (1907), "Atherton", A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 3, Victoria County History, pp. 435–439, retrieved 17 March 2010CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Brandwood et al. (2012), pp. 111–112

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 2 February 2020

- Brandwood et al. (2012), p. 230

- Brandwood et al. (2012), pp. 112, 239

- Pollard & Pevsner (2006), pp. 136–137.

- Brandwood et al. (2012), p. 112

- Market Place, Atherton: Conservation Area Appraisal (PDF), Wigan Council, April 2008, p. 14, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Potts 2006, p. 378

- Lancashire (Manchester, Greater), Atherton, St. John the Baptist (N00634), British Institute of Organ Studies, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Lancashire (Manchester, Greater), Atherton, St. John the Baptist (N00635), British Institute of Organ Studies, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Listed Buildings, English Heritage, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Brandwood et al. (2012), p. 111

Sources

- Brandwood, Geoff; Austin, Tim; Hughes, John; Price, James (2012), The Architecture of Sharpe, Paley and Austin, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 978-1-84802-049-8

- Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006), Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10910-5, retrieved 19 October 2012

- Potts, Michael (2006), Potts of Leeds - Five Generations of Clockmakers, Mayfield Books, ISBN 0-9523270-8-2

- Wright, John James (1921), The Story of Chowbent Chapel 1645-1721-1921, H. Rawson

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to St John the Baptist, Atherton. |