Patuxet

The Patuxet were a Native American band of the Wampanoag tribal confederation. They lived primarily in and around modern-day Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Patuxet have been extinct since 1622.

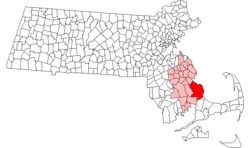

Patuxet Village | |

|---|---|

Historic area of the Patuxet tribe | |

| Coordinates: 41°57′30″N 70°40′04″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Plymouth |

| Settled | Unknown |

| Defunct | ~1617 |

| Elevation | 187 ft (57 m) |

| Population | 0 |

Devastation

The Patuxet were wiped out by a series of plagues that decimated the indigenous peoples of southeastern New England in the second decade of the 17th century. The epidemics which swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes between 1614 and 1620 were especially devastating to the Wampanoag and neighboring Massachuset, with mortality reaching 100% in many mainland villages. When the Pilgrims landed in 1620, all the Patuxet except Squanto had died.[2] The plagues have been attributed variously to smallpox,[3] leptospirosis,[4] and other diseases.[5][6][7][8]

The last Patuxet

Some European expedition captains were known to increase profits by capturing natives to sell as slaves. Such was the case when Thomas Hunt kidnapped several Wampanoag in 1614 in order to sell them later in Spain. One of Hunt's captives was a Patuxet named Tisquantum. Tisquantum eventually came to be known as Squanto (a nickname given to him by his friend William Bradford). After Squanto regained his freedom, he was able to work his way to England where he lived for several years, working with a shipbuilder.

He signed on as an interpreter for a British expedition to Newfoundland. From there Squanto went back to his home, only to discover that, in his absence, epidemics had killed everyone in his village.[2]

Squanto succumbed to "Indian fever" in November 1622.[9]

The Pilgrims

The first settlers of Plymouth Colony (modern Plymouth, Massachusetts), sited their colony at the location of a former Patuxet village, named "Port St. Louis" (Samuel de Champlain, 1605) or "Accomack" (John Smith, 1614). By 1616, the site had been renamed New Plimoth in Smith's A Description of New England after a suggestion by Prince Charles of England. When the Pilgrim Settlers decided to make their settlement, the land that had been cleared and cultivated by the prior inhabitants (since dead through disease) was a primary reason for the location.

Squanto was instrumental in the survival of the colony of English settlers at Plymouth. Samoset, a Pemaquid (Abenaki) sachem from Maine, introduced himself to the Pilgrims upon their arrival in 1620. Shortly thereafter, he introduced Squanto (presumably because Squanto spoke better English) to the Pilgrims, who had settled at the site of Squanto's former village.[2] From that point onward, Squanto devoted himself to helping the Pilgrims. Whatever his motivations, with great kindness and patience, he taught the English the skills they needed to survive, including how best to cultivate varieties of the Three Sisters: beans, maize and squash.

Although Samoset appears to have been important in establishing initial relations with the Pilgrims, Squanto was undoubtedly the main factor in the Pilgrims' survival. In addition, he also served as an intermediary between the Pilgrims and Massasoit, the Grand Sachem of the Wampanoag (original name Ousamequin [10] or "Yellow Feather"[11]). As such, he was instrumental in the friendship treaty that the two signed, allowing the settlers to occupy the area around the former Patuxet village.[2] Massasoit honored this treaty until his death in 1661.[12]

Thanksgiving

In the fall of 1621, the Plymouth colonists and Wampanoag shared an autumn harvest feast. This three-day celebration involving the entire village and about 90 Wampanoag has been celebrated as a symbol of cooperation and interaction between English colonists and Native Americans.[13] The event later inspired 19th century Americans to establish Thanksgiving as a national holiday in the United States. The harvest celebration took place at the historic site of the Patuxet villages. Squanto's involvement as an intermediary in negotiating the friendship treaty with Massasoit led to the joint feast between the Pilgrims and Wampanoag. This feast was a celebration of the first successful harvest season of the colonists.[2]

See also

- List of Native American Tribal Entities

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Town of Plymouth. Geographic Names Information System. Retrieved on 2007-07-31.

- Sultzman, Lee. "Wampanoag History". tolatsga.org. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "Wampanoag Tribe". Mahalo.com.

- Marr, JS; Cathey, JT (February 2010). "New hypothesis for cause of an epidemic among Native Americans, New England, 1616–1619". Emerg Infect Dis. 16 (2): 281–6. doi:10.3201/eid1602.090276. PMC 2957993. PMID 20113559.

- Webster N (1799). A brief history of epidemic and pestilential diseases. Hartford CT: Hudson and Goodwin.

- Williams, H (1909). "The epidemic of the Indians of New England, 1616–1620, with remarks on Native American infections". Johns Hopkins Hospital Bulletin. 20: 340–9.

- Bratton, TL (1988). "The identity of the New England Indian epidemic of 1616–19". Bull Hist Med. 62 (3): 351–83. PMID 3067787.

- Speiss A, Speiss BD (1987). "New England pandemic of 1616–1622. cause and archeological implication". Man in the Northeast. 34: 71–83.

- "A history of the Wampanoag". CapeCodOnline.com. 16 February 2007. Archived from the original on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "Native People of Massachusetts". Archived from the original on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- Cline, Duane A. (2001). "The Massasoit Ousa Mequin". rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "History & Culture". MashpeeWampanoagTribe.com. 23 June 2008. Archived from the original on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- "The First Thanksgiving". history.com. The History Channel. Archived from the original on 25 February 2009. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

Further reading

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1908). Sowams, with Ancient Records of Sowams and Parts Adjacent. New Haven: Associated Publishers of American Records.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. New York: Knopf.

- Moondancer and Strong Woman. A Cultural History of the Native Peoples of Southern New England: Voices from Past and Present. (Boulder, Colorado: Bauu Press), 2007.

- Rowlandson, Mary. The Sovereignty and Goodness of God. (Boston: Bedford Books), 1997.

- Salisbury, Neal. Manitou and Providence. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 1982.

- Salisbury, Neal and Colin G. Calloway, eds. Reinterpreting New England Indians and the Colonial Experience. Vol. 71 of Publications of the Colonial Society of Massachusetts. (Boston: University of Virginia Press), 1993.

- Salisbury, Neal. Introduction to The Sovereignty and Goodness of God by Mary Rowlandson. (Boston: Bedford Books), 1997.

External links

- The First Thanksgiving

- Inspired By A Dream: Linguistics Grad Works to Revive the Wampanoag Language, MIT Spectrum, Spring 2001

- Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project

- Plimoth Plantation webpage

- Plymouth, MA

- CapeCodOnline's Wampanoag landing page

- Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe

- www.mayflowerfamilies.com "Native People" page

- Ancestry.com