South Fork Trinity River

The South Fork Trinity River is the main tributary of the Trinity River, in the northern part of the U.S. state of California.[1] It is part of the Klamath River drainage basin. It flows generally northwest from its source in the Klamath Mountains, 92 miles (148 km) through Humboldt and Trinity Counties, to join the Trinity near Salyer. The main tributaries are Hayfork Creek and the East Branch South Fork Trinity River.[2] The river has no major dams or diversions, and is designated Wild and Scenic for its entire length.

| South Fork Trinity River | |

|---|---|

South Fork Trinity River at the Highway 299 bridge | |

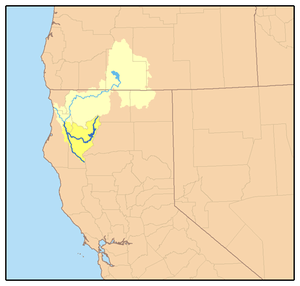

Map of the Trinity River watershed with the South Fork extending south from the mainstem; watershed highlighted in yellow | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Region | Klamath Mountains, Humboldt County, Trinity County |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Unnamed spring |

| • location | North Yolla Bolly Mountain, Trinity County |

| • coordinates | 40°09′24″N 122°59′18″W |

| • elevation | 5,921 ft (1,805 m) |

| Mouth | Trinity River |

• location | Salyer, Trinity County |

• coordinates | 40°53′23″N 122°36′08″W |

• elevation | 446 ft (136 m) |

| Length | 92 mi (148 km) |

| Basin size | 980 sq mi (2,500 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Salyer |

| • average | 1,807 cu ft/s (51.2 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 35 cu ft/s (0.99 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 95,400 cu ft/s (2,700 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • right | East Branch South Fork Trinity River, Hayfork Creek |

One of the largest undammed river systems in California, the South Fork drains a rugged, remote watershed of 980 square miles (2,500 km2). The large areas of intact habitat are important for several endangered species and rare plants. Historically, the South Fork watershed was known for its prodigious anadromous fish population and dense old-growth forests. During the mid-20th century, the river channel was heavily damaged by major flooding, which was exacerbated by erosion caused by mining, logging and ranching. Decades later the South Fork is still considered in the process of recovery.[3]

Course

The South Fork Trinity River begins as a small spring on the west slope of the Brooks Ridge near North Yolla Bolly Mountain, 4,460 feet (1,360 m) above sea level.[1] From there, it flows briefly west and turns to the north, receiving numerous small tributaries which drain a series of steep, forested valleys in the headwaters. At about 4 miles (6.4 km) from its source, the river is crossed by the Humboldt Trail, then it receives north-flowing Shell Mountain Creek from the west. Shortly downstream, the 10-mile (16 km) long East Branch South Fork Trinity River joins from the east.[1][4][5] Shortly afterwards, it receives Happy Camp Creek from the west and Smoky Creek from the east.

Below here the river passes Forest Glen, receives Rattlesnake Creek from the east, and crosses underneath California State Route 36. Here the river runs roughly parallel to the Mad River, separated by a 2,000-foot (610 m) divide to the west. Below State Route 36, it receives Butter and Indian Valley Creeks, both from the east.[1][4][5]

The river then enters the wide Hyampom Valley, where it passes the town of Hyampom and receives its biggest tributary, Hayfork Creek, from the east. It then passes the Hyampom Airport and receives Pelletreau Creek from the west. Within the valley the river briefly exhibits braided characteristics, with a wide floodplain. At the north end of the valley the river enters another canyon, receiving Mingo Creek from the west, then veers sharply eastward and then turns sharply north again. The river receives Madden Creek from the west and crosses underneath California State Route 299. Directly below the bridge, the South Fork flows north into the Trinity River.[1][4][5]

Geology

Over hundreds of millions of years, the westward movement of North America caused it to accrete many terranes from the Pacific Ocean region along its west coast. Four major terranes have so far collided with the northwest coast of California—the oldest dating to pre-Jurassic times—crumpling the crust upwards into the 10,000-foot (3,000 m)-high massif of the Klamath Mountains. Most of the Klamath Mountains consist of granite and batholiths underlie most of the major peaks. The second most recent of the terranes—dating to the Cretaceous—which is composed almost entirely of granite, brought with it a strip of mica that roughly aligns with the present course of the South Fork Trinity River. The mica caused the granite to become weaker than the surrounding rock, so this area was subjected to greater erosion that created the valley of the South Fork, the lower Trinity River, and the lower Klamath River. This is also why the Klamath and Trinity rivers have this sharp northwest bend on their generally southwest courses, and the South Fork Trinity River valley is the southernmost extension of the roughly 200-mile (320 km)-long gorge formed by this abundance of mica.

The vast majority of the South Fork watershed is mountains, with the only level land found in the Hyampom Valley at the confluence of the river and Hayfork Creek, along the Hayfork valley, and along narrow river terraces. There are large parts of the watershed where the ground is composed of stable bedrock, while large portions of hillsides are composed of loose soil and rock. Historically, riverbeds in the watershed were narrow and rocky, but due to vast amounts of silt washed down by poor logging practices, streambeds have become wide, braided, elevated and shallow.[6]

Watershed

The river and its tributaries drain 980 square miles (2,500 km2) in Trinity County in the south and Humboldt County and Trinity County in the north and comprising 34 percent of the 2,853-square-mile (7,390 km2) Trinity River watershed. The Hayfork Creek sub-watershed contains 379 square miles (980 km2), or 38 percent of the entire South Fork Trinity watershed. Most of the watershed lies on public lands (79 percent), while for Hayfork Creek, 78 percent of its watershed lies on public lands.[2] With the Yolla Bolly Mountains in the south and the Klamath Mountains in the north, the topography of the South Fork Trinity's watershed is dissected by deep gorges and valleys separated by narrow ridges. The South Fork is the longest undammed National Wild and Scenic River in California.[7] (The Eel River, also a Wild and Scenic River, is over twice as long, but is dammed near its headwaters. The Smith River drains a greater area but is much shorter.)

While along the length of the South Fork itself there is little human development, it receives agricultural pollutants from Hayfork Creek, whose valley contains over 52,000 acres (210 km2) of ranchlands and farmlands. In fact, there have been sightings of frequent fish kills in Hayfork Creek and it is said to have "severe water quality problems in the summer".[6] Diversions off Hayfork Creek have only furthered the pollution problem by concentrating it. Logging and road-building are the two primary negative factors affecting the South Fork mainstem. Clearing hillsides has accelerated erosion, clouding the water and causing difficulties for steelhead trout and chinook salmon, which once spawned in the river in prodigious numbers. Although logging has mostly ceased since the designation of the national forest, the landscape has not yet fully recovered from its impacts.[3]

Much of the South Fork Trinity River's watershed is the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, which covers most of the mountainous areas in the southern and central part of the watershed, and the Six Rivers National Forest, which covers most of the northern third of the basin. Nearly the entire length of the South Fork above the Hayfork Creek confluence is inside the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, while below the confluence, national forest lands peter out into privately owned land and the river then enters Six Rivers National Forest. Most of the upper and lower Hayfork Creek reaches also are in the Shasta-Trinity forest, while a large amount of private land surrounds its middle reach in Hayfork Valley and the town of Hayfork. Throughout nearly the entire watershed, there are sporadic patches of private lands and Bureau of Land Management-owned lands.[5]

Streamflow

The river flows into the Trinity River northwest of Salyer. The United States Geological Survey monitors the South Fork Trinity River's flow at four gauges; these are at Salyer, downstream of Hyampom, at Hyampom upstream of the Hayfork Creek confluence, and Forest Glen (from mouth to source).[8] The average flow of the river at its mouth is 1,807 cubic feet per second (51.2 m3/s).[9] For Salyer, closest to the mouth, the highest peak flow was 95,400 cubic feet per second (2,700 m3/s) on December 22 in the 1964 flood, while the lowest was 8,480 cubic feet per second (240 m3/s) on 31 December 1954.[10] For the location downstream of Hyampom, the highest recorded peak flow was 88,000 cubic feet per second (2,500 m3/s) on 22 December 1964, while the lowest was 620 cubic feet per second (18 m3/s).[11] For the location at Hyampom, the highest peak was 57,000 cubic feet per second (1,600 m3/s) on 22 December 1964, while the lowest was 5,020 cubic feet per second (142 m3/s) on 13 February 1962.[12] For Forest Glen, the largest peak was 41,200 cubic feet per second (1,170 m3/s) on 22 December 1964, and the lowest was 3,530 cubic feet per second (100 m3/s) on 13 February 1962.[13]

History

For what may have been hundreds of years, the South Fork Trinity River had a rich history of Native Americans. The river annually produced enormous salmon runs, one of the richest sub-basins in the Trinity watershed, and virgin old-growth forests covered most of the watershed. In the 19th century, many events the largest of which was the California Gold Rush spurred Europeans, Americans and others to flood the region in search of furs, and later gold. One particular trail crossed through the Yolla Bolly Mountains, then wound down to Hayfork Creek and west to the South Fork Trinity.[14] In the 1930s, hydraulic mining was already taking place at the Swanson Mine near the mouth of the river. Beginning in the late 1940s, logging companies moved into the South Fork Trinity's watershed. It was said that the "big logging started when Pat Veneer came in",[15] referring to a logging company from Oregon. It was not long before debris and silt began to cloud the creeks feeding the South Fork, many of which were still located on United States Forest Service land.

In the Christmas flood of 1964, heavy rains washed enormous amounts of silt and debris from clear-cut lands into the river, and killing entire fish and amphibian populations. The flood peaked on 22 December at 95,400 cubic feet per second (2,700 m3/s).[16] It was said that the "South Fork is a lost cause, a 'dead river' which will never recover from the devastation of the 1964 storms."[15] Even decades after the flooding, erosion rates in the watershed remain much higher than the pre-1964 average. By the 1970s, anadromous fish populations saw a significant decline as a direct result of siltation.

In 1947, Six Rivers National Forest, which encompasses most of the northernmost quarter of the South Fork Trinity's watershed, was established.[17] By 1954, the Shasta–Trinity National Forest, which covers the vast majority of the South Fork Trinity River's watershed, was established, bringing nearly 70 percent[5] of the South Fork watershed under federal protection.[18][19] In 1980, the United States Forest Service designated the South Fork National Recreation Trail, which runs from Forest Glen to near its headwaters.[14]

Fish and wildlife

In 1964 before the floods, the spring chinook salmon run was estimated to be as large as 10,000 and with a minimum of 3,400, which declined to an annual run of between 345 and 2,460 prior to 1990. Due to the gradual recovery of the mountainsides after logging, salmon runs have once again begun to return, averaging 2,000 to 4,000.[20] Although the water from the South Fork continues down the Trinity to the Klamath and eventually, the Pacific Ocean, undammed, the diversion of most of the Trinity main stem's water and pollution in the Klamath have made access to the river difficult for migrating fish. It is of note that part of the reason of the declined population is a high mortality rate of female salmon, resulting in less offspring. Generally in summer, temperatures in the river can rise to over 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 degrees Celsius), which allow introduced species, including green sunfish to flourish and compete with salmon.[6]

Remaining old-growth forests in the South Fork watershed provide vital habitat for several threatened and near-threatened species, including the northern spotted owl.[3]

See also

- Trinity River topics

- South Fork Eel River, which has ecology, geography, and a history of logging very similar to that of the South Fork Trinity.

- List of rivers of California

References

- "South Fork Trinity River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 19 January 1981. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "Where and What is the South Fork Trinity River Watershed?" (PDF). South Fork Trinity River Coordinated Resources Management Planning Group. Trinity County Resource Conservation District. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "California Rivers: South Fork Trinity River". Friends of the River. www.friendsoftheriver.org. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- Map of the South Fork Trinity River (Map). Cartography by NAVTEQ. Google Maps. 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "South Fork Trinity River Watershed Final TMDL (includes ownership)" (PDF). GIS Group Watershed Analysis Center. Environmental Protection Agency. 22 September 1998. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "Action Plan for Restoration of the South Fork Trinity River Watershed and Its Fisheries (Part Two)". Pacific Watershed Associates. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Trinity River Task Force. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "Trinity River (California)". National Wild and Scenic Rivers Program. www.rivers.gov. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- "NWIS search results for "Trinity R"". United States Geological Survey.

- "USGS Gage #11519000 on the South Fork Trinity River at Salyer". National Water Information System. 5 February 1951 to 19 December 1982. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-07-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "USGS Gage #11529000 on the South Fork Trinity River at Salyer". National Water Information System. 5 February 1951 to 19 December 1982. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-07-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "USGS Gauge #11528700 on the South Fork Trinity River below Hyampom". National Water Information System. 22 December 1964 to present day. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-07-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "USGS Gage #11528200 on the South Fork Trinity River near Hyampom". National Water Information System. 22 December 1955 to 22 December 1964. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-07-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "USGS Gage #11528200 on the South Fork Trinity River at Forest Glen". National Water Information System. 23 November 1955 to 22 December 1964. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2009-07-30.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "South Fork National Recreation Trail" (PDF). United States Forest Service. www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- Berol, Emelia (Summer 1995). "A River History: Conversations with Long-term Residents of the Lower South Fork Trinity River" (PDF). South Fork Trinity River Coordinated Resources Management Planning Group. Retrieved 2009-07-29.

- USGS streamflow data for four stream gauges along the South Fork

- "Six Rivers National Forest". United States Forest Service. www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- "Shasta-Trinity National Forest: General Forest History". United States Forest Service. www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- Harmon, Donna. "Shasta-Trinity National Forest: South Fork Management Unit". United States Forest Service. www.fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2009-07-30.

- "Action Plan for Restoration of the South Fork Trinity River Watershed and Its Fisheries (Part One)". Pacific Watershed Associates. U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Trinity River Task Force. Retrieved 2009-07-29.