Soft-paste porcelain

Soft-paste porcelain (sometimes simply "soft paste", or "artificial porcelain") is a type of ceramic material in pottery, usually accepted as a type of porcelain. It is weaker than "true" hard-paste porcelain, and does not require either the high firing temperatures or the special mineral ingredients needed for that. There are many types, using a range of materials. The material originated in the attempts by many European potters to replicate hard-paste Chinese export porcelain, especially in the 18th century, and the best versions match hard-paste in whiteness and translucency, but not in strength.[2] But the look and feel of the material can be highly attractive, and it can take painted decoration very well.[3]

.jpg)

The ingredients varied considerably, but always included clay, often ball clay, and often ground glass, bone ash, soapstone (steatite), flint, and quartz. They rarely included the key ingredients necessary for hard-paste, china clay including kaolin, or the English china stone,[4] although some manufacturers included one or other of these, but failed to get their kilns up to a hard-paste firing temperature. They were called "soft paste" (after the French "pâte tendre") either because the material is softer in the kiln, and prone to "slump", or their firing temperatures are lower compared with hard-paste porcelain,[5] or, more likely, because the finished products actually are far softer than hard-paste, and early versions were much easier to scratch or break, as well as being prone to shatter when hot liquid was suddenly poured into them.[6]

The German Meissen porcelain had developed hard-paste porcelain by 1708, and later German factories usually managed to find the secret out from former Meissen employees, beginning with Vienna porcelain in 1718.[7] The other European countries had much longer to wait, but most factories eventually switched from soft to hard-paste, having discovered both the secret and a source of kaolin. In France kaolin was only found in Limousin in 1768, and Sèvres produced both types from 1769, before finally dropping soft-paste in 1804.[8] In England there was a movement in a different direction, as Spode's formula for bone china, developed in the 1790s, was adopted by most other factories by about 1820. By that point little soft-paste porcelain was being made anywhere, and little hard-paste in England, with Nantgarw and Swansea in Wales among the last factories making soft-paste.[9]

Background

There were early attempts by European potters to replicate Chinese porcelain when its composition was little understood and its constituents were not widely available in the West. The earliest formulations were mixtures of clay and ground-up glass (frit). Soapstone (steatite) and lime are also known to have been included in some compositions. The first successful attempt was Medici porcelain, produced between 1575 and 1587. It was composed of white clay containing powdered feldspar, calcium phosphate and wollastonite (CaSiO3), with quartz.[10][11] Other early European soft-paste porcelain, also a frit porcelain, was produced at the Rouen manufactory in 1673, which was known for this reason as "Porcelaine française".[12] Again, these were developed in an effort to imitate high-valued Chinese hard-paste porcelain.[12] As these early formulations slumped in the kiln at high temperatures, they were difficult and uneconomic to use. Later formulations used kaolin (china clay), quartz, feldspars, nepheline syenite and other feldspathic rocks. Soft-paste porcelain with these ingredients was technically superior to the traditional soft-paste and these formulations remain in production.

Characteristics

Soft-paste formulations containing little clay are not very plastic[13] and shaping it on the potter's wheel is difficult. Pastes with more clay (now more commonly referred to as "bodies"), such as electrical porcelain, are extremely plastic and can be shaped by methods such as jolleying and turning. The feldspathic formulations are, however, more resilient and suffer less pyroplastic deformation. Soft-paste is fired at lower temperatures than hard-paste porcelain, typically around 1100 °C[14][15] for the frit based compositions and 1200 to 1250 °C for those using feldspars or nepheline syenites as the primary flux. The lower firing temperature gives artists and manufacturers some benefits, including a wider palette of colours for decoration and reduced fuel consumption. The body of soft-paste is more granular than hard-paste porcelain, less glass being formed in the firing process.

According to one expert, with a background in chemistry, "The definition of porcelain and its soft-paste and hard-paste varieties is fraught with misconceptions",[16] and various categories based on the analysis of the ingredients have been proposed instead.[17] Some writers have proposed a "catch-all" category of "hybrid" porcelain, to include bone china and various "variant" bodies made at various times.[18] This includes describing as "hybrid soft-paste porcelain" pieces made using kaolin but apparently not fired at a sufficiently high temperature to become true hard-paste, as with some 18th-century English and Italian pieces.[19]

At least in the past, some sources dealing with modern industrial chemistry and pottery production have made a completely different distinction between "hard porcelain" and "soft porcelain", by which all forms of pottery porcelain, including East Asian wares, are "soft porcelain".[20]

European soft-paste

Chinese porcelain, which arrived in Europe before the 14th century, was much admired and expensive to purchase. Attempts were made to imitate it from the 15th century onwards but its composition was little understood. Its translucency suggested that glass might be an ingredient,[21] so many experiments combined clay with powdered glass (frit), including the porcelain made in Florence in the late 16th century under the patronage of the Medicis. In Venice there were experiments supposedly using opaque glass alone.[22]

German factories either made hard-paste from their foundation, like Meissen, Vienna, Ludwigsburg, Frankenthal and later factories, or obtained the secret and switched. France did in fact make hard-paste at Strasbourg in 1752-54, until Louis XV gave his own factory, Vincennes, a monopoly, at which point the factory moved to become the Frankenthal operation.[23]

Early factories in France, England, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, Holland, Switzerland and other countries made soft-paste, the switch to hard-paste generally coming after 1750, with France and England rather in the rear, as explained below.[24] The American China Manufactory (or Bonnin and Morris) in Philadelphia, America's first successful porcelain factory, also made soft-paste from about 1770-72.[25]

France

Experiments at the Rouen manufactory produced the earliest soft-paste in France, when a 1673 patent was granted to Louis Poterat, but it seems that not much was made. An application for the renewal of the patent in 1694 stated, "the secret was very little used, the petitioners devoting themselves rather to faience-making". Rouen porcelain, which is blue painted, is rare and difficult to identify.[26]

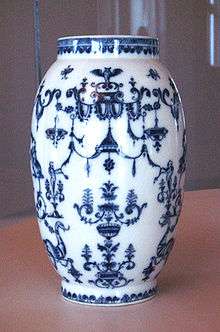

The first important French porcelain was made at the Saint-Cloud factory, which was an established maker of faience. In 1702, letters-patent were granted to the family of Pierre Chicaneau, who were said to have improved upon the process discovered by him, and since 1693 to have made porcelain as "perfect as the Chinese". The typical blue-painted Saint-Cloud porcelain, says Honey, "is one of the most distinct and attractive of porcelains, and not the least part of its charm lies in the quality of the material itself. It is rarely of a pure white, but the warm yellowish or ivory tone of the best wares of the period is sympathetic and by no means a shortcoming; and while actually very soft and glassy, it has a firm texture unlike any other. The glaze often shows a fine satin-like pitting of the surface that helps to distinguish it from the brilliant shiny glaze of Mennecy, which is otherwise similar. The heavy build of the pieces is also characteristic and is saved from clumsiness by a finer sense of mass, revealed in the subtly graduated thickness of wall and a delicate shaping of edges."[27]

Louis Henry de Bourbon, prince de Condé established a soft-paste factory on the grounds of his château de Chantilly in 1730; Chantilly porcelain continued to be made after his death in 1740.

A soft-paste factory was opened at Mennecy by François Barbin in 1750. The Vincennes porcelain factory was established in 1740 under the supervision of Claude-Humbert Gérin, who had previously been employed at Chantilly. The factory moved to larger premises at Sèvres[28] in 1756. A superior soft-paste was developed at Vincennes, whiter and freer of imperfections than any of its French rivals, which put Vincennes/Sèvres porcelain in the leading position in France and throughout the whole of Europe in the second half of the 18th century.[29]

The use of frit in this paste lent it the names "Frittenporzellan" in Germany and "frita" in Spain. In France it was known as "pâte tendre" and in England "soft-paste",[27] perhaps because it does not easily retain its shape in the wet state, or because it tends to slump in the kiln under high temperature, or because the body and the glaze can be easily scratched. (Scratching with a file is a crude way of finding out whether a piece is made of soft-paste or not.)

England

The first soft-paste in England was demonstrated by Thomas Briand to the Royal Society in 1742 and is believed to have been based on the Saint-Cloud formula. In 1749, Thomas Frye, a portrait painter, took out a patent on a porcelain containing bone ash. This was the first bone china, subsequently perfected by Josiah Spode.

Recipes were closely guarded, as illustrated by the story of Robert Brown, a founding partner in the Lowestoft factory, who is said to have hidden in a barrel in Bow to observe the mixing of their porcelain.[30] A partner in Longton Hall referred to "the Art, Secret or Mystery" of porcelain.[31]

In the fifteen years after Briand's demonstration, several factories were founded in England to make soft-paste table-wares and figures:[32]

- Chelsea 1743 [33][34]

- Bow 1745.[35][36][37]

- St James's 1748 (or "Girl on a Swing")[37][38]

- Longton Hall 1750 [39]

- Royal Worcester 1751

- Derby 1757 [40][41]

- Lowestoft 1757 [42]

.jpg)

Chinese soft-paste porcelain

Unlike the European product, Chinese porcelain began with hard-paste, and it is common to regard all Chinese production as hard-paste,[43] until bone china began to be made there in the 20th century. However, a classification of "Chinese soft-paste porcelain" is often recognised by museums and auction-houses,[44] though its existence may be denied by others.[45]

It refers to pieces of Chinese porcelain, mostly from the first half of the 18th century, that are less translucent than most Chinese porcelain and have a rather milky-white glaze, which is prone to crackling. Some regard it as essentially made from a hard-paste body that did not reach a sufficiently high firing temperature, or uses a different glaze formula. It takes underglaze cobalt blue painting especially well, which is one of the factors leading it to be identified as the wares using a mineral ingredient called huashi, mentioned by Father François Xavier d'Entrecolles in his published letters describing Chinese production.[46] It used to be thought that the special ingredient was soapstone (aka "French chalk", a form of steatite), as used in some English porcelain. However chemical analsis of samples shows no sign of this.[47]

Hard-paste porcelain

Hard-paste porcelain was successfully produced at Meissen in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus, though Johann Friedrich Böttger who continued his work has often been credited with the discovery of this recipe. As the recipe was kept secret, experiments continued elsewhere, mixing glass materials (fused and ground into a frit) with clay or other substances to give whiteness and a degree of plasticity. Plymouth porcelain, founded in 1748, which moved to Bristol soon after, was the first English factory to make hard-paste.[48]

Notes

- "Porcelain plate". Ceramics. Victoria and Albert Museum. Retrieved 2007-12-06.

- Edwards, 3-6

- Battie, 104; Edwards, 4

- Edwards, 1-6

- Honey (1977), 4; Rado, P, An Introduction To The Technology Of Pottery, 2nd edition. Pergamon Press, 1988

- Honey (1977), 2, 4, 8

- Battie, 88-102

- Honey (1977), 3; Battie, 107-109

- Honey (1977), 4-5; see Edwards for the Welsh factories.

- Marco Spallanzani, Ceramiche alla Corte dei Medici nel Cinquecento, (Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore, and Modena: Franco Cosimo Panini, 1994), p. 69.

- According to on-site Raman spectroscopic analyses performed at the Musée National de Céramique, Sèvres, reported in Ph. Colomban, V. Milande, H. Lucas, "On-site Raman analysis of Medici porcelain", Journal of Raman Spectroscopy, 35.1 (2003:68-72).

- Artificial Soft Paste Porcelain - France, Italy, Spain and England Edwin Atlee Barber p.5-6

- Honey (1952), p.296

- Fournier, p.214

- Lane, p.21

- Edwards, 4

- Edwards, 4-6

- Edwards, 3-4

- Hess, Catherine (2003), Italian Ceramics: Catalogue of the J. Paul Getty Museum Collections, pp 230, 237 note 7, 2003, Getty Publications, ISBN 0892366702, 9780892366705, google books

- Inorganic Chemistry, by A. F. Holleman, Egon Wiberg, Nils Wiberg, Editor Nils Wiberg, 2001, Academic Press, ISBN, 0123526515, 9780123526519, google books; see also Singer and Singer, pp. 104-1102

- Honey (1952), p.496

- Honey (1952), p.497

- Battie, 88-102

- Battie, 102-113

- Metropolitan Museum

- Honey (1952), p.528

- Honey (1952), p.533

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Savage (1983), p.215

- Savage, (1983), p.212

- All covered by Honey (1977) - see Index or Contents

- ‘Science Of Early English Porcelain.’ I.C. Freestone. Sixth Conference and Exhibition of the European Ceramic Society. Vol.1 Brighton, 20–24 June 1999, p.11-17

- ‘The Sites Of The Chelsea Porcelain Factory.’ E.Adams. Ceramics (1), 55, 1986.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-12-03. Retrieved 2011-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-02-04. Retrieved 2011-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-12-03. Retrieved 2011-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ‘Ceramic Figureheads. Pt. 3. William Littler And The Origins Of Porcelain In Staffordshire.’ Cookson Mon. Bull. Ceram. Ind. (550), 1986.

- History of Royal Crown Derby Co Ltd, from "British Potters and Potteries Today", publ 1956

- 'The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory, and the Chinese Porcelain Made for the European Market during the Eighteenth Century.' L. Solon. The Burlington Magazine. No. 6. Vol.II. August 1906.

- Edwards, 4

- example in the Walters Art Museum; example in the Metropolitan Museum; Lot 3205 "A FINE AND RARE DING-TYPE GLAZED SOFT-PASTE VASE, QIANLONG INCISED SIX-CHARACTER SEAL MARK AND OF THE PERIOD (1736-1795)" Christie's, Hong Kong, Sale 3265, Imperial Chinese Porcelain: Treasures from a Distinguished American Collection, 27 November 2013, another example

- Edwards, 4

- Valenstein, 242

- Savage & Newman, 267-268

- Honey (1977), Chapter 14

References

- Atterbury, Paul (ed.), The History of Porcelain (Orbis, 1982)

- Battie, David, ed., Sotheby's Concise Encyclopedia of Porcelain, 1990, Conran Octopus. ISBN 1850292515

- Edwards, Howell G.M., Nantgarw and Swansea Porcelains: An Analytical Perspective, 2018, Springer, ISBN 3319776312, 9783319776316, google books

- Fournier, Robert, Illustrated Dictionary of Practical Pottery (Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1973)

- Honey, W.B. (1952), European Ceramic Art (Faber and Faber, 1952)

- Honey, W.B. (1977), Old English Porcelain: A Handbook for Collectors, 1977, 3rd edn. revised by Franklin A. Barrett, Faber and Faber, ISBN 0571049028

- Lane, Arthur, English Porcelain Figures of the 18th Century (Faber and Faber, 1961)

- Leach, Bernard, A Potter's Book (Faber and Faber, 1940)

- Rado, Paul, An Introduction To The Technology Of Pottery (Pergamon Press, 1988)

- Savage, George, and Newman, Harold, An Illustrated Dictionary of Ceramics, 1985, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500273804

- Savage, George, English Ceramics (Jean F. Gouthier, 1983)

- Savage, George, Porcelain Through the Ages (Penguin Books, 1963)

- Singer, F. and Singer, S.S., Industrial Ceramics (Chapman Hall, 1963)

- Valenstein, S. (1998). A handbook of Chinese ceramics, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. ISBN 9780870995149 (fully online)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Soft-paste porcelain. |

.jpg)