Slimonidae

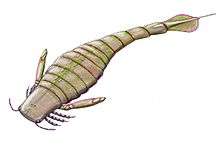

Slimonidae (the name deriving from the type genus Slimonia, which is named in honor of Welsh fossil collector and surgeon Robert Slimon) is a family of eurypterids, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Slimonids were members of the superfamily Pterygotioidea and the family most closely related to the derived pterygotid eurypterids, which are famous for their cheliceral claws and great size. Many characteristics of the Slimonidae, such as their flattened and expanded telsons (the posteriormost segments of their bodies), support a close relationship between the two groups.

| Slimonidae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of Slimonia acuminata housed at the Senckenberg Museum of Frankfurt | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Infraorder: | †Diploperculata |

| Superfamily: | †Pterygotioidea |

| Family: | †Slimonidae Novojilov, 1962 |

| Type species | |

| †Slimonia acuminata Salter, 1856 | |

| Genera | |

Slimonids are defined as pterygotioid eurypterids with swimming legs similar to those of the type genus, Slimonia, and the second to fifth pair of appendages being non-spiniferous. The family contains only two genera, the almost completely known Slimonia and Salteropterus, which is known only from the telson and the metastoma (a large plate part of the abdomen).

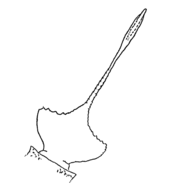

Both slimonid genera preserve flattened and expanded telsons that end in elongated telson spikes. The discovery of several articulated specimens of Slimonia with the tail segments preserved in tight curves, suggesting that the tail segments were considerably more flexible than previously thought and would have been capable of considerable side-to-side movement. Unlike the related pterygotids, the slimonids did not possess robust and powerful cheliceral claws and as such, these telson spikes may have been the primary weaponry used by Slimonia, although this theory is considered unlikely by contemporary researchers. The telson spike of Salteropterus was likely not used as a weapon and was highly distinct and different from that of any other eurypterid.

Description

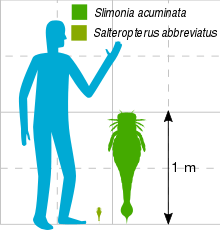

Slimonid eurypterids ranged in size from 12 centimetres (5 inches) to 100 centimetres (39 inches) in length. The largest species was Slimonia acuminata, which was also the first slimonid to be described and is known from the Early to Middle Silurian of Lesmahagow, Scotland.[1]

Like all other chelicerates, and other arthropods in general, slimonid eurypterids possessed segmented bodies and jointed appendages (limbs) covered in a cuticle composed of proteins and chitin. The chelicerate body is divided into two tagmata (sections); the frontal prosoma (head) and posterior opisthosoma (abdomen). The appendages were attached to the prosoma, and were characterized in slimonids as being non-spiniferous (lacking spines).[2] The telson (the posteriormost segment of the body) was expanded and flattened (similarly to the telsons of the more derived pterygotid eurypterids) and ended in a thin and elongated telson spike.[3] In Salteropterus, this telson spike was even more elongated than in Slimonia and ended in a tri-lobed structure unique to the genus.[4]

Though Slimonia itself is very well known, the other genus of the family, Salteropterus, is less well known with its fossils only preserving the telson and the metastoma (a large plate part of the abdomen).[2] As such it is difficult to establish exactly which traits distinguish the family as a whole from the other pterygotioid eurypterid families (Pterygotidae and Hughmilleriidae), even though several defining traits are known of Slimonia. Many of the unique traits of Slimonia are found in the carapace (the "head"), which is not known in Salteropterus. Among these is the quadrate (square) shape of the carapace itself and the placement of the compound eyes on the frontal corners.[5] Though they were closely related, the Slimonidae had small and non-developed chelicerae (frontal appendages) in comparison to the Pterygotidae, which possessed well-developed and powerful cheliceral claws.[5]

History of research

The type species of Slimonia, S. acuminata, was first described as a species of Pterygotus, "Pterygotus acuminata", by John William Salter in 1856 based on fossils that had been discovered in Lesmahagow, Scotland. That same year David Page erected a new genus to contain the species, as several distinctive characteristics made the species considerably different from other known species of Pterygotus, among them the shape of the carapace and P. acuminata lacking the large cheliceral claws otherwise characteristic of Pterygotus.[6] The genus was named "Slimonia" after Robert Slimon, honoring the Welsh fossil collector and surgeon who was the first to discover eurypterid fossils in Lesmahagow.[7]

In the late 1800s and early 1900s new specimens were discovered of a previously fragmentary species of Eurypterus, E. abbreviatus, in Herefordshire, England.[4] One of these specimens, BGS GSM Zf-2864 (discovered in 1939), revealed a very distinct telson and features similar to Slimonia (such as the last three opisthosomal segments tapering in a way similar to in Slimonia), which suggested a close relation between this species and Slimonia.[4]

The family Slimonidae was erected as a taxon by Nestor Ivanovich Novojilov in 1962 to contain the genus Slimonia, which was considered sufficiently distinct from the genera housed in its previous family, the Hughmilleriidae. After several features had been noted that suggested a close relationship between Salteropterus and Slimonia (particularly similarities in the abdominal segments), Salteropterus was finally classified as a slimonid in 1989 by Victor P. Tollerton.[8]

Paleobiology

The large and flattened telson of Slimonia (it is also flattened in Salteropterus, but not to the full extent of that of Slimonia) is distinctive and shared only with the pterygotid eurypterids and with the derived hibbertopterid Hibbertopterus and mycteroptid Hastimima, where a flattened telson had convergently evolved.[9]

The function of these specialized telsons has historically been controversial and disputed, and whilst study has mainly been focused on telsons within the Pterygotidae, the similarity between the telson of Slimonia and its close relatives should mean that the function would likely have been similar. The pterygotids were hypothesized to have moved by undulating the entire opisthosoma (the large posterior section of the body) by moving the abdominal plates, as such undulations of the opisthosoma and telson would have acted as the propulsive method of the animal, rendering the swimming legs used by other eurypterid groups useless.[10] Fossil evidence contradicts such an hypothesis however, as eurypterid bodies were stiff dorsally (up and down) and preserve no evidence for any sort of tapering or other mechanism that would have increased flexibility. Any flexing of the body would require muscular contractions, but no major apodemes (internal ridges of the exoskeleton that supports muscular attachments) or any muscle scars indicative of large opisthosomal muscles have been found.[9] Instead, propulsion was likely generated by the sixth pair of appendages, the swimming legs used by other eurypterine eurypterids.[9]

Whilst stiff dorsally, fossil evidence suggests that Slimonia was very flexible laterally (side to side). A specimen of Slimonia acuminata from the Patrick Burn Formation of Scotland preserves a complete and atriculated series of telsonal, postabdominal and preabdominal segments. In the specimen, the "tail" is bent to a considerable degree previously unseen in any eurypterid. Capable of bending its tail from side to side, it has been theorised that the tail may have been used as a weapon. The telson spine, serrated along the sides and exceeding the flattened telson in length, ends in a sharp tip and would likely have been capable of piercing prey.[3] In pterygotids, it is likely that the cheliceral claws came to replace telson spikes as weaponry as the telson spikes of that family are relatively shorter than those of the Slimonidae.[3] However, this theory has been proven to be erroneous as the fossil specimen in question was a molt, rather than an actual carcass, and did show apparent signs of disarticulation.[10]

The telson of Salteropterus is very distinctive and though its function remains unknown (possibly used for additional balancing), it was likely not used as a weapon in the same way the telson of Slimonia was. The flattened portion is trigonal and smaller than that of Slimonia but the telson spike is far longer, forming something akin to a stem with knobs running alongside it and ending in a tri-lobed organ unseen in any other eurypterid.[4]

Classification

Slimonid eurypterids are classified as part of the Pterygotioidea superfamily, within the Diploperculata infraorder and Eurypterina suborder.[11] The Slimonidae is often interpreted as a sister-taxon (the most closely related group) to the Pterygotidae. The other Pterygotioid family, the Hughmilleriidae, has also been interpreted as the most closely related sister-taxon to the pterygotids. The discovery of Ciurcopterus, currently the most primitive known pterygotid, allowed researchers to study its features which showed that the primitive pterygotid combined characteristics of more derived members of its own family and Slimonia. In particular, the similar appendages shared between the two genera suggested that the Slimonidae was the most closely related group to the Pterygotidae. Hughmilleriid eurypterids are thus seen as a group more basal than both the slimonids and the pterygotids.[12]

The cladogram below is based on the conclusions drawn by O. Erik Tetlie (2004) on the phylogenetic positions of Herefordopterus, Salteropterus and the Pterygotioidea at large following his redescriptions of various eurypterids from Herefordshire, England, including Salteropterus. The partial lack of spines on the appendages of both slimonid genera unites them as a group and showcases that they are more derived than the hughmilleriids, on which spines appear on four to five of their podomeres (leg segments).[8]

| Pterygotioidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009-10-14). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters: rsbl20090700. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information

- Tollerton, V. P. (1989). "Morphology, taxonomy, and classification of the order Eurypterida Burmeister, 1843". Journal of Paleontology. 63 (5): 642–657. doi:10.1017/S0022336000041275. ISSN 0022-3360.

- Persons, W. Scott; Acorn, John (2017). "A Sea Scorpion's Strike: New Evidence of Extreme Lateral Flexibility in the Opisthosoma of Eurypterids". The American Naturalist. 190 (1): 152–156. doi:10.1086/691967. PMID 28617636.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1951). "Downtonian (Silurian) Eurypterida from Perton, near Stoke Edith, Herefordshire". Geological Magazine. 88 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1017/S0016756800068874. ISSN 1469-5081.

- Størmer, L 1955. Merostomata. Treatise on Invertebrate Paleontology, Part P Arthropoda 2, Chelicerata, P: 30.

- Nicholson, Henry Alleyne (1868-01-01). "III. On the Occurrence of Fossils in the Old Red Sandstone of Westmoreland". Transactions of the Edinburgh Geological Society. 1 (1): 15–18. doi:10.1144/transed.1.1.15. ISSN 0371-6260.

- Clarkson, Euan N.K.; Harper, David A.T. (2016). "Silurian of the Midland Valley of Scotland and Ireland". Geology Today. 32 (5): 195–200. doi:10.1111/gto.12152.

- Tetlie, O. Erik (2006). "Eurypterida (Chelicerata) from the Welsh Borderlands, England". Geological Magazine. 143 (5): 723–735. doi:10.1017/S0016756806002536. ISSN 1469-5081.

- Plotnick, Roy E.; Baumiller, Tomasz K. (1988-01-01). "The pterygotid telson as a biological rudder". Lethaia. 21 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1988.tb01746.x. ISSN 1502-3931.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1964). "A Synopsis of the Family Pterygotidae Clarke and Ruedemann, 1912 (Eurypterida)". Journal of Paleontology. 38 (2): 331–361. JSTOR 1301554.

- Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2015. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern, online at http://wsc.nmbe.ch, version 16.0 http://www.wsc.nmbe.ch/resources/fossils/Fossils16.0.pdf (PDF).

- Tetlie, O. Erik; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2009-09-01). "The origin of pterygotid eurypterids (Chelicerata: Eurypterida)". Palaeontology. 52 (5): 1141–1148. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2009.00907.x. ISSN 1475-4983.