Skomer

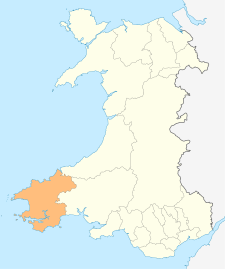

Skomer (Welsh: Ynys Sgomer) or Skomer Island[1] is an island off the coast of Pembrokeshire, in the community of Marloes and St Brides[2][3] in west Wales. It is well known for its wildlife: around half the world's population of Manx shearwaters nest on the island, the Atlantic puffin colony is the largest in southern Britain, and the Skomer vole (a subspecies of the bank vole) is unique to the island. Skomer is a national nature reserve, a Site of Special Scientific Interest and a Special Protection Area. It is surrounded by a marine nature reserve and is managed by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales.

| Native name: Ynys Sgomer | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg) Skomer viewed from Martin's Haven | |

Skomer | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Jack Sound |

| Coordinates | 51.73611°N 5.29628°W |

| Area | 2.92 km2 (1.13 sq mi) |

| Length | 3.2 km (1.99 mi) |

| Width | 2.4 km (1.49 mi) |

| Administration | |

Wales | |

| County | Pembrokeshire |

| Community | Marloes and St Brides |

| Additional information | |

| grid reference SM725093 | |

Skomer is known for its archaeological interest: stone circles, standing stone and remains of prehistoric houses. Much of the island has been designated an ancient monument.

Description

The island has an area of 2.92 km2 (720 acres).[4] Its highest point is 79 m (259 ft) above sea level at Gorse Hill, while the majority of the island sits at around 60 m (200 ft) above sea level. Skomer is intersected by a series of slopes and ridges giving it a rich and varied topography. It is approximately 2.4 km (1.5 mi) from north–south and 3.2 km (2.0 mi) east–west.

The island is almost cut in two near its eastern side by two bays.[5][6] It is one of several islands lying within a kilometre of the Pembrokeshire coast. A number of islets surround Skomer, the largest of which are: Midland Isle (height 50 metres, 164 feet) separated from Skomer by Little Sound, Mew Stone (60 metres, 197 feet) and Garland Stone (32 metres, 105 feet).[7]

Name

The name Skomer derives from Skalmey, a name of Viking origin meaning "Cleft island", possibly from the fact that the eastern end of the island is nearly cut off from the main part.[8] It is marked on a 1578 map in Latin as Scaline Insul, with the first word probably meaning scalene or unequal.[9]

Geology

The volcanic rocks of which Skomer is comprised date from the Silurian period around 440 million years ago. A series of basalts, rhyolites, felsites, keratophyres, mugearite and associated sedimentary rocks (quartzites, etc.) are grouped together as the 'Skomer Volcanic Series'. The series which is up to 1000m thick also includes trachyte, dolerite and skomerite which is an altered andesite.[10] Basalt is the most common component of this sequence; some of it appears as pillow lava indicating that it was erupted under water. Other basalt flows show signs of contemporary subaerial weathering.[11]

This same suite of rocks can also be traced eastwards on the mainland along the northern side of the Marloes peninsula and extends almost as far east as St Ishmael's. The entire sequence on Skomer dips between 15° and 25° to the south-southeast. It is cut by several faults, notably those responsible for the erosion of the inlets of North Haven and South Haven. A NW-SE aligned fault stretches between Bull Hole and South Haven, offsetting the strata on either side.[12]

Skomer was cut off from the mainland by rising sea levels after the last Ice Age.

History

There is evidence of human occupation—field boundaries and settlement remains—dating back to the Iron Age.[13]

The Skomer Island Project, run jointly by the Royal Commission for Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales (RCAHMW) with archaeologists from the University of Sheffield and Cardiff University, started in 2011, investigates the island's prehistoric communities. Airborne laser scanning together with ground excavations continued in 2016 and established that human settlement dates back 5,000 years.[14] Rabbits were introduced in the 14th century and their burrows and grazing have had a profound effect on the island landscape.[13]

It was last permanently inhabited by the Codd family (all year round) in 1950. After the Second World War, the owner had offered the West Wales Field Society, now The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales, the opportunity to make a survey of Skomer which was accepted and Skomer opened for visitors from April 1946.[15] The farm buildings in the centre of the island, now housing visitor accommodation, were refurbished in 2005.[13] Skomer was featured in the BBC TV documentary Coast in Episode 4 of Series 5 (first aired August 2010).

David Saunders MBE was in 1960 the first warden of Skomer.[16]

Wildlife

Skomer is best known for its large breeding seabird population, including Manx shearwaters, guillemots, razorbills, great cormorants, black-legged kittiwakes, Atlantic puffins, European storm-petrels, common shags, Eurasian oystercatchers and gulls, as well as birds of prey including short-eared owls, common kestrels and peregrine falcons. The island is also home to grey seals, common toads, slow-worms, a breeding population of glow-worms and a variety of wildflowers. Harbour porpoises occur in the surrounding waters. The Skomer vole, a subspecies of bank vole, is endemic to the island.

Atlantic puffin

There are around 10,000 breeding pairs of puffins on Skomer and Skokholm Islands, making them one of the most important puffin colonies in Britain. They arrive in mid-April to nest in burrows, many of which have been dug by the island's large rabbit population. The last puffins leave the island by the second or third week in July. They feed mainly on small fish and sand eels; often puffins can be seen with up to a dozen small eels in their beaks.

After a period of declining numbers between the 1950s and 1970s, the size of the colony is growing again at 1–2% a year (as of 2006). By 2004, there were numerous puffin burrows on the island and adults flying back with food run across the walkways oblivious to the tourists. A 2019 survey estimated a population of 24,108 birds.[17]

Manx shearwater

In 2011, an estimated 310,000[13]:78 pairs of Manx shearwater were breeding on Skomer, with around 40,000 pairs on the "sister" island Skokholm. A 2019 survey estimated the Skomer population at almost 350,000, a 10 per cent increase. The colony comprises around half the world population and make the islands the world's most important breeding site for the species. The birds usually nest in rabbit burrows, a pair reportedly using the same burrow year after year.[17]

Shearwaters are not easy to see as they come and go at dusk, but a closed-circuit television camera in one of the burrows allows subterranean nesting activity to be seen on the screen in Lockley Lodge on the mainland at Martin's Haven. The remains of shearwaters killed by the island's population of great black-backed gulls can also be seen. An overnight stay in the hostel run by the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales allows guests to hear and see the shearwaters.

The Manx shearwater has a remarkable life. After fledging the young birds migrate to the South Atlantic off the coasts of Brazil and Argentina. They remain there at sea for five years before returning to breed on their natal island. On their return they navigate back to within a few metres of the burrow in which they were born. As they are ungainly and vulnerable on the land, they leave their burrows at dawn for the fishing grounds some fifty kilometres north out in the Irish Sea, not returning until dusk. Thus they attempt to avoid the gulls to which they would fall easy prey.

Skomer vole

Skomer has one unique mammal: the Skomer vole (Myodes glareolus skomerensis), a distinct form of the bank vole. The lack of land-based predators on the island means that the bracken habitat is an ideal place for the vole, with the population reaching around 20,000 during the summer months. Then the resident short-eared owls may be seen patrolling the areas close to the farmhouse in the centre of the island for voles to feed their young.

Access

Boats sail to Skomer from Martin's Haven on the mainland, a sheltered 15-minute trip every day (weather dependent) except Monday (Whitsun Bank Holiday Monday excepted) from April to September between 10am and noon (actual times may vary). Return sailings are from 3pm but the boatman will advise on the day. There are limits on the number of people allowed to visit the island (250 per day). Advance booking is not permitted and reservations are strictly on a first come, first served basis at Lockley Lodge in Martin's Haven and long queues can develop early each morning in peak season.[18]

A self-catering hostel with 16 beds is situated at the farm in the centre of the island. Booking opens in October and can only be done by phoning the Tondu office. Overnight guests are brought over on a separate boat trip on the morning of their stay and the hostel is open April to September.[19]

Areas open for visitor access are restricted to pathways. The Neck, an eastern area connected only by a narrow isthmus, is entirely out of bounds to visitors.

In 2005–06, there was a renovation project of the farm buildings which included the old barn for improved overnight visitor and research accommodation, the volunteers' quarters were rebuilt and the warden's house at North Haven was also rebuilt. Solar power provides hot water and electricity for lighting.

See also

References

- "Skomer Island". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- "Marloes and St. Brides". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- Ordnance Survey mapping

- "Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales: Skomer Island". Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- Island Naturalist, Wildlife Trust West Wales, Autumn 1998, no. 36 ISSN 1367-6466

- Island Naturalist, Dyfed Wiildlife Trust, Autumn 1996, no. 32, ISSN 0955-1735, pp. 24–29

- "Bing Maps". Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- "History of Skomer (factsheet)" (PDF). Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- "Penbrok comitat". British Library.

- Jackson, Klaus & Neuendorf. 2005 Glossary of Geology 5th Edition, American Geological Institute

- Howells, M.F. 2007 British Regional Geology: Wales (Keyworth, Nottingham, British Geological Survey)

- British Geological Survey 1978 1:50,000 scale geological map sheet (England & Wales) 226/227 Milford, Keyworth, Notts

- Matthews, Jane (2007). Skomer: Portrait of a Welsh Island. Graffeg. ISBN 978-1-905582-08-2.

- Jon Coles (28 April 2016). "The Skomer Island Project". Pembrokeshire Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2016.

- Island of Skomer, John Buxton and Ronald Lockley, Staples Press, 1950.

- Bruce Sinclair (10 April 2017). "Bird migration talk at Pembroke Dock's library". Western Telegraph. Retrieved 20 October 2017.

- "Skomer island's Manx shearwater census shows 10% rise". BBC News. 19 May 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- "Visiting Skomer". Archived from the original on 4 June 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- "Overnight accommodation on Skomer". Archived from the original on 7 February 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Skomer Island. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Skomer. |