Skid row

A skid row or skid road is an impoverished area, typically urban, in English-speaking North America whose inhabitants are people "on the skids". This specifically refers to the poor, the homeless or others either considered disreputable or forgotten by society.[1] A skid row may be anything from an impoverished urban district to a red-light district to a gathering area for the homeless. In general, skid row areas are inhabited or frequented by individuals marginalized by poverty or through drug addiction. Urban areas considered skid rows are marked by high vagrancy, and they often feature cheap taverns, dilapidated buildings, and drug dens as well as other features of urban blight. Used figuratively, it may indicate the state of a poor person's life.

The term skid road originally referred to the path along which timber workers skidded logs.[2] Its current sense appears to have originated in the Pacific Northwest.[3] Areas identified by this name include Pioneer Square in Seattle;[4] Old Town Chinatown in Portland, Oregon;[5] Downtown Eastside in Vancouver; Skid Row in Los Angeles; the Tenderloin District of San Francisco; and the Bowery of Lower Manhattan.

Origins

The term "skid road" dates back to the 17th century, when it referred to a log road, used to skid or drag logs through woods and bog.[3] The term was in common usage in the mid-19th century and came to refer not just to the corduroy roads themselves, but to logging camps and mills all along the Pacific Coast. When a logger was fired he was "sent down the skid road."[6]

The source of the term "skid road" as an urban district is heavily debated, and is generally identified as originating in either Seattle or Vancouver.

Seattle

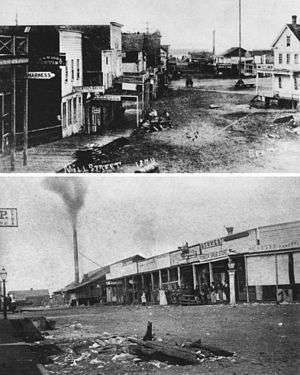

The name "Skid Road" was in use in Seattle by 1850s when the city's historic Pioneer Square neighborhood began to expand from its commercial core.[7] The district centered near the end of what is now Yesler Way, the original "Skid Road" named after the freshly‑cut logs that were skidded downhill toward Henry Yesler’s mill.[8]

Henry Yesler acquired land from Doc Maynard at a small point of land at what is today near the intersection of 1st Avenue and Yesler Way. He also acquired a swath of land 450 feet wide from his property up First Hill to a box of land about 10 acres in size full of timber spanning what is today 20th to 30th Avenues. Logs would be moved down the skid road of Yesler Way to his mill.[9] In the words of Murray Morgan, "This district south of Yesler Way, this land below the Deadline, has helped fix the word on the American language. The Skid Road: the place of dead dreams."[10] His steam-powered logging mill was built in 1853[7] on the point of land that looked south towards a small island (Denny's Island, part of his land purchase from Doc Maynard) that has since been filled in around and is the heart of today's Pioneer Square. The mill operated seven days a week, 24 hours per day on the waterfront.[7] The street's end near the mill, attracted cookhouses and inexpensive hotels for itinerant workers, along with several establishments that served beer and liquor.[7]

The Skid Road was built on that 450 foot wide slice of land from the top of First Hill to the logging mill on the point. Timber cut in nearby forests was greased and skidded down a long, steeply sloping dirt road.[7] Since the building of the mill much of what is today's Seattle is the result of extensive terra-forming by the local people to make the hilly landscape of Seattle habitable. At the time of the building of the mill it was some of the only flat land available. The Skid Road became the demarcation line between the affluent members of Seattle and the mill workers and more rowdy portion of the population.[11] The road became Mill Street, and eventually Yesler Way, but the nickname "Skid Road" was permanently associated with the district at the street's end.[7]

Vancouver

The 100-block of East Hastings Street in Vancouver, British Columbia, the heart of that city's "skid road" neighborhood, lies on a historical skid road. The Vancouver Skid Road was part of a complex of such roads in the dense forests surrounding the Hastings Mill and adjacent to the settlement of Granville, Burrard Inlet (Gastown).[12]

The city began as a sawmill settlement called Granville, in the early 1870s.[13] By at least the 1950s, "Skid Road" was commonly used to describe the more dilapidated areas in the city's Downtown Eastside,[14] which is focused on the original "strip" along East Hastings Street due to a concentration of single room occupancy hotels (SROs) and associated drinking establishments in the area. The area's seedy origins date back to the early concentration of saloons in pre-Canadian Prohibition (1915–1919) and its popularity with loggers, miners and fishermen whose work was seasonal and who spent their salaries in the area's cheap accommodations and public houses.

Opium and heroin use became popular early on; Vancouver was for many years the main port-of-entry for the North American opium supply. During the Great Depression, the railway rights-of-way and other vacant lots in the area were thronged by the unemployed and poor, and the pattern of social decay became well-established. In the 1970s, the endemic alcohol and poverty problems in the area were exacerbated by the expansion of the drug trade, with crack cocaine becoming high-profile in the 1980s as well as a reconcentration of the prostitution trade in the area because of the relocation of hooker strolls in conjunction with city policy for Expo 86.

A portion of Vancouver's Skid Row, Gastown, has also been gentrified; however it is in a difficult coexistence with the nearby impoverished Downtown Eastside along East Hastings Street.

The Downtown Eastside is deemed to be one of the poorest urban areas in Canada.[15] It is wedged between popular tourist destinations such as Downtown, Chinatown and Gastown. East Hastings Street is also a major thoroughfare. These avenues of exposure make the Downtown Eastside a highly visible example of a skid row.

The Downtown Eastside (sometimes abbreviated D.T.E.S.) is also home to Insite, the first legal intravenous drug safe injection site in North America, part of a harm reduction policy aimed at helping the area's drug addicted residents. Additional sites have been established with approval from Health Canada in 2017 and 2018 as part of the strategy for dealing with the epidemic of lethal opioid (primarily fentanyl) overdoses.

Los Angeles

Local homeless count estimates have ranged from 3,668 to 8,000.[16][17] In 2011, the homeless population estimate for Los Angeles' Skid Row was 4,316.[18] L.A.'s Skid Row is sometimes called "the Nickel", referring to a section of Fifth Street.[19]

Several of the city's homeless and social-service providers (such as Weingart Center Association, Volunteers of America, Frontline Foundation, Midnight Mission, Union Rescue Mission and Downtown Women's Center) are based in Skid Row. Between 2005 and 2007, several local hospitals and suburban law-enforcement agencies were accused by Los Angeles Police Department and other officials of transporting those homeless people in their care to Skid Row.[20][21]

San Francisco

The Tenderloin neighborhood is a small, dense neighborhood near downtown San Francisco. In addition to its history and diverse and artistic community, there is significant poverty, homelessness, and crime.[22]

It is known for its immigrant populations, single room occupancy hotels, ethnic restaurants, bars and clubs, alternative arts scene, large homeless population, public transit and close proximity to Union Square, the Financial District, and Civic Center.[22] The 2000 census reported a population of 28,991 persons, with a population density of 44,408/mi² (17,146/km²), in the Tenderloin's 94102 Zip Code Tabulation Area, which also includes the nearby Hayes Valley neighborhood.[23]

During the 1960s, when development interests and the Redevelopment Agency were using eminent domain to clear out a large area populated by retired men in the South of Market area, that area was termed "Skid Row" in the media. The City's convention center was built after the clearing of long term low-income residents.[24][25]

New York

In New York, Skid Row was a nickname given to the Bowery during much of the 20th century.[26]

Chicago

Traditional Skid Row areas in Chicago were centered along West Madison Street just west of the Chicago River[27] and, to a lesser degree, North Clark Street just north of the Chicago River.[28] Since the 1980s both of these areas have been gentrified.

Philadelphia

Philadelphia once had a highly visible skid row centered on Vine Street, just west of the approaches to the Benjamin Franklin Bridge. This area was essentially obliterated by highway construction starting in the 1970s.[29][30]

Today, the area most often referred to as Philadelphia's modern-day skid row is in the Kensington neighborhood, along Kensington Avenue near the intersections of Somerset Street and Allegheny Avenue. The area is known for its high rates of open-air recreational drug use, poverty, and homelessness.[31] A long-time camp largely hidden from public view in a gulch alongside Conrail tracks, spanning an area roughly from N 2nd Street to Kensington Avenue, was cleared in 2017.[32] In late 2018, the city cleared a series of large homeless camps along Kensington Avenue, Emerald Street, Tulip Street, and Frankford Avenue.[33] The homeless population in the Kensington neighborhood alone is estimated to be over 700 individuals.[34]

Houston

In the 1800s much of what was the Third Ward, the present day south side of Downtown Houston. According to some, the eastern boundary is a low rent group of houses near Texas Southern University referred to as "Sugar Hill." and among musicians, the Third Ward's boundaries are usually thought of as extending southward from the junction of Interstate 45 (Gulf Freeway) and Interstate 69/U.S. Route 59 (Southwest Freeway) to the Brays Bayou, with Main Street forming the western boundary. The Third Ward was what Stephen Fox, an architectural historian who lectured at Rice University, referred to as "the elite neighborhood of late 19th-century Houston." Ralph Bivins of the Houston Chronicle said that Fox said that area was "a silk-stocking neighborhood of Victorian-era homes." Bivins said that the construction of Union Station, which occurred around 1910, caused the "residential character" of the area to "deteriorate." Hotels opened in the area to service travelers. Afterwards, according to Bivins, the area "began a long downward slide toward the skid row of the 1990s" and the hotels were changed into flophouses. Passenger trains stopped going to Union Station. The City of Houston abolished the ward system in the early 1900s, but the name "Third Ward" was continued to be used to refer to the territory that it used to cover.[35]

Popular references

- "The Wall Street Shuffle" by 10cc mentions Skid row in the lyrics.

- "Skid Row" is the name of an American heavy metal band formed in New Jersey.

- "Skid Row" is also the name of a Dublin, Ireland-based blues-rock band from the late 1960s and early 1970s that included such musicians as singer Phil Lynott and guitarist Gary Moore, both of whom later were part of Thin Lizzy.

- Kurt Cobain, playing in a band that at the time had no name, came up with the name "Skid Row" to put on the marquee at a gig on the spur of the moment. That band's name would change frequently after that. He would later go on to form Nirvana.[36]

- SKiDROW is one of the prominent warez groups in software. Whether this is based on the band is unknown.

- Breaking Bad Season 4 Episode 4 features Jesse turning his house into a Skid Row for the homeless.

- The Little Shop of Horrors films and subsequent musical are all set in various downtown neighborhoods called Skid Row and include the song Skid Row (Downtown). The original 1960 film was set in Los Angeles while the 1982 musical and its 1986 film adaptation were set in New York.

- In Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo, Scotty, played by Jimmy Stewart, says "Why, that's Skid Row" in response to hearing a MIssion-xxxx (MI or 64 prefix) phone number. He's referring to the Dogpatch shipyard in San Francisco, on the east waterfront side of Potrero Hill. Back then, the MIssion telephone exchange covered all the southern city.

- In Rocky, near the beginning of the movie Mick gives Rocky's gym locker to another prospect who in Mick's eyes deserves it more. When Rocky discovers this on his next visit he says "I've had this locker for six years and you hang my stuff on skid row". There are other various references throughout the Rocky films.

- Lana Del Rey sings "I wear my diamonds on skid row" on "Cola", a song from her second studio album titled Born To Die: The Paradise Edition

- Skidrow is the name of the dystopian neighborhood where the player character of the 1999 video game Kingpin: Life of Crime begins his quest for revenge.

See also

References

Notes

- "Skid Row". Collins English Dictionary – Complete & Unabridged (2012 Digital ed.). HarperCollins. 2012.

- "Skid road". The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

A squalid district inhabited chiefly by derelicts and vagrants. [Alteration of SKID ROAD (from the fact that it once referred to a downtown area frequented by loggers).]

- Turner, Wallace (December 2, 1986). "A Clash Over Aid Effort on the First 'Skid Row'". The New York Times. p. A20. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Portland's History". Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- Rochester, Junius; Crowley, Walt (October 17, 2002). "Yesler, Henry L. (1810–1892)". History Ink. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- Keniston-Longrie, Joy (2009). Seattle's Pioneer Square. Chicago, San Francisco, & Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7385-7144-7.

- Morrison, Patt (1987-03-24). "Original 'Skid Road': Homeless Add a Sad Note to Gentrified Seattle Area". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on 2015-10-25.

Yesler Way—the nation’s original ‘Skid Row’ . . . Skid Road was christened here in the 1850s, when logs were ‘skidded’ by horses, mules or oxen down the steep, timber‑lined path to Henry Yesler’s thriving sawmill on Elliott Bay.

- Speidel, William (1967). Sons of the Profits. Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Company. pp. 62, 223–224.

- Morgan, Murray (2018). Skid Road. University of Washington Press. pp. 8–9, 30–31. ISBN 9780295743493.

- William C. Speidel, "Sons of the Profits, The Seattle Story 1851 to 1901"

- "Gastown". Virtual Vancouver. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- "About Vancouver". City of Vancouver. 2007. Retrieved 2007-01-27.

- "Demolish City's Skid Road, Murder Protest Demands." Vancouver Sun. April 6, 1962. p. 1.

- Kalache, Stefan (January 12, 2007). "The Poorest Postal Code Vancouver's Downtown Eastside in Photos". The Dominion. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- Cristi, Chris (June 13, 2019). "LA's homeless: Aerial view tour of Skid Row, epicenter of crisis". ABC7.

- "Rats, trash and typhoid: Los Angeles' growing shantytown slum". News.com.au. June 4, 2019.

- "2011 Greater Los Angeles Homeless Count (page 38 – Skid Row section)" (PDF). Los Angeles Homeless Services Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-11-16.

- "For Some, L.A.'s Skid Row Is For Beginnings". NPR. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- "LA Downtown News Online". Downtownnews.com. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- "A Plan to Spread Homeless Countywide". Los Angeles Times. 2006-03-24. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006.

- The Sidewalks of San Francisco by Heather Mac Donald, City Journal Autumn 2010. City-journal.org (2010-10-14). Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- American FactFinder, United States Census Bureau. "941 3-Digit ZCTA by 5-digit ZIP Code Tabulation Area – GCT-PH1. Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2000". Factfinder.census.gov. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- Hartman, Chester. 1984. The Transformation of San Francisco. Totowa, NJ: Rowman & Allanheld.

- Averbach, Alvin. 1973. "San Francisco's South of Market District, 1858–1958: The Emergence of a Skid Row." California Historical Quarterly 52(3):196223.

- Jesse McKinley (2002-10-13). "Along the Bowery, Skid Row Is on the Skids". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-06.

- Witter, David (August 11, 2010). "How Chicago's Skid Row Went From "The Land of the Living Dead" to Cappuccinos and Condos | Newcity".

- "Charles W. Cushman Photograph Collection>> Results >> Details". indiana.edu.

- "Philadelphia Begins Demolition Of It's (sic) Skid Row".

- "Waiting for the Wrecking Ball: Skid Row in Postindustrial Philadelphia".

- "Skid Row Deaths Of 1963 Echoes Today's Opioid Crisis". Hidden City Philadelphia.

- "Cleanup work along Philly Conrail tracks reaches 'El Campamento' heroin haven".

- Whelan, Aubrey. "As snow falls, Philly clears another Kensington heroin encampment". inquirer.com.

- Whelan, Aubrey. "Philadelphia's annual homeless count reveals new realities about the opioid crisis". inquirer.com.

- Wood, Roger. Down in Houston: Bayou City Blues (Issue 8 of Jack and Doris Smothers series in Texas history, life, and culture). 2003, University of Texas Press. 1st Edition. ISBN 0292786638, 9780292786639.

- Ian Halperin; Max Wallace (1999). Who Killed Kurt Cobain?: The Mysterious Death of an Icon. Carol Publishing Group. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8065-2074-2.

Bibliography

- Holbrook, Stewart H. (1961). "Yankee Loggers". New York: International Paper Company. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). - Newell, Gordon (1956). "Totem Tales of Old Seattle". Seattle: Superior Publishing Company. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). - Morgan, Murray (1960). "Skid Road". Ballantine Books. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (revised edition; first edition was 1951).

External links

- Some Seattle history

- Pioneer Square history

- Guardian Article

- Down On Skid Row, A Tape's Rolling! Special Documentary produced by Twin Cities Public Television

- A group page for Portland, Oregon's "Felony Flats"

- Yelp review page for Portland's "Felony Flats"

- Article from 2008 on gentrification in Portland's "Felony Flats"

- Opinion column from a Portland cab driver on "Felony Flats"