Skanderbeg's rebellion

Skanderbeg's rebellion was an almost 25-year long anti-Ottoman rebellion led by the renegade Ottoman sanjakbey Skanderbeg in the territory which belonged to the Ottoman sanjaks of Albania, Dibra and Ohrid (modern-day Albania and Macedonia). The rebellion was the result of initial Christian victories in the Crusade of Varna in 1443. After Ottoman defeat in the Battle of Niš, Skanderbeg, then sanjakbey of the Sanjak of Debar, mistakenly believed that Christians would succeed in pushing the Ottomans out of Europe. Like many other regional Ottoman officials, he deserted the Ottoman army to raise rebellion in his sanjak of Dibra and the surrounding region. Initially, his plan was successful and soon large parts of the Sanjak of Dibra and north-east parts of the Sanjak of Albania were captured by the rebels who also fought against regular Ottoman forces in the Sanjak of Ohrid.[2] According to Oliver Schmitt, Castrioti was allowed to leave the Ottoman army thanks to the intervention of his aunt Mara Branković, who was his mother's sister and one of the wives of sultan Murat II.[3]

| Skanderbeg's rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

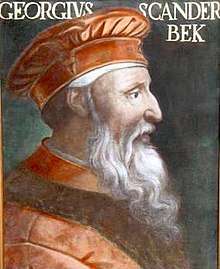

Skanderbeg's portrait | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

League of Lezhë (1444-50)

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| League of Lezhë (1444-1450) | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| maximum 10,000-15,000 | maximum 100,000-150,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Heavy | ||||||

The rebellion of Skanderbeg was a rare successful instance of resistance by Christians during the 15th century and through his leadership led Albanians in guerrilla warfare against the Ottomans.[4] Skanderbeg's rebellion was not, however, a general Albanian uprising; many Albanians did not join it and some even fought against it for the Sultan, nor were his forces exclusively drawn from Albanians. Rather, his revolt represents a reaction by certain sections of local society and feudal lords against the loss of privilege and the exactions of the Ottoman government which they resented. In addition the rebels fought against members of their own ethnic groups because the Ottoman forces, both commanders and soldiers, were also composed of local people (Albanians, Slavs, Vlachs, Greeks and Turkish timar holders).

Skanderbeg managed to capture Krujë using a forged letter of the sultan and, according to some sources, impaled captured Ottoman officials who refused to be baptized into Christianity.[5] On 2 March 1444 the regional Albanian and Serbian chieftains united against the Ottoman Empire and established an alliance (League of Lezhë) which was dissolved by 1450.

Because of the frequent conflicts between rival families in Albania during Skanderbeg's rebellion, particularly between Skanderbeg and Leke Dukagjini, Albanian studies scholar Robert Elsie described the period as more of an Albanian civil war.[6]

Background

In Albania, the rebellion against the Ottomans had already been smouldering for years before Skanderbeg deserted the Ottoman army.[7] The most notable earlier revolt was revolt of 1432–36 led principally by Gjergj Arianiti. Although Skanderbeg was summoned by his relatives during this rebellion, he remained loyal to the sultan and did not fight the Ottomans.[8] After this rebellion was suppressed by the Ottomans, Arianiti again revolted against the Ottomans in the region of central Albania in August 1443.[9]

Skanderbeg decided to leave his position of Ottoman sanjakbey and revolt against the Ottomans only after the victorious Crusade of Varna in 1443.[10] Successes of the crusaders inspired revolt of Skanderbeg and revolt of Constantine XI Palaiologos in the Despotate of the Morea.[11] In early November 1443, Skanderbeg deserted the forces of Sultan Murad II during the Battle of Niš, while fighting against the crusaders of John Hunyadi.[12] Skanderbeg quit the field along with 300 other Albanians serving in the Ottoman army.[13] He immediately led his men to Krujë, where he arrived on November 28,[14] and by the use of a forged letter from Sultan Murad to the Governor of Krujë he became lord of the city.[15] To reinforce his intention of gaining control of the former domains of Zeta, Skanderbeg proclaimed himself the heir of the Balšić family. After capturing some less important surrounding castles (Petrela, Prezë, Guri i Bardhë, Svetigrad, Modrič and others) and eventually gaining control over more than his father Gjon Kastrioti's domains, Skanderbeg abjured Islam and proclaimed himself the avenger of his family and country.[16] He raised a red flag with a black double-headed eagle on it: Albania uses a similar flag as its national symbol to this day.[17]

Forces

Skanderbeg's rebellion was not a general uprising of Albanians. People from the big cities in Albania on the Ottoman-controlled south and Venetian-controlled north did not support him while his followers beside Albanians were also Slavs, Vlachs and Greeks.[18] The rebels did not fight against "foreign" invaders but against members of their own ethnic groups because the Ottoman forces, both commanders and soldiers, were also composed of local people (Albanians, Slavs, Vlachs and Turkish timar holders).[19] Dorotheos, the Archbishop of Ohrid and clerics and boyars of Ohrid Archbishopric together with considerable number of Christian citizens of Ohrid were expatriated by sultan to Istanbul in 1466 because of their anti-Ottoman activities during Skanderbeg's rebellion.[20] Skanderbeg's rebellion was also supported by Greeks in the Morea.[21] According to Fan Noli, the most reliable counselor of Skanderbeg was Vladan Jurica.[22]

League of Lezhë (1444–1450)

On 2 March 1444 the regional Albanian and Serbian chieftains united against the Ottoman Empire.[23] This alliance (League of Lezhë) was forged in the Venetian held Lezhë.[24] A couple of months later Skanderbeg's forces stole cattle of the citizens of Lezhë and captured their women and children.[25] The main members of the league were the Arianiti, Balšić, Dukagjini, Muzaka, Spani, Thopia and Crnojevići. All earlier and many modern historians accepted Marin Barleti's news about this meeting in Lezhë (without giving it equal weight), although no contemporary Venetian document mentions it.[26] Barleti referred to the meeting as the generalis concilium or universum concilium [general or whole council]; the term "League of Lezhë" was coined by subsequent historians.[27]

Early battles

Kenneth Meyer Setton claims that majority of accounts on Skanderbeg's activities in the period 1443–1444 "owe far more to fancy than to fact."[28] Soon after Skanderbeg captured Krujë using the forged letter to take control from Zabel Pasha, his rebels managed to capture many Ottoman fortresses including strategically very important Svetigrad (Kodžadžik) taken with support of Moisi Arianit Golemi and 3,000 rebels from Debar.[29] According to some sources, Skanderbeg impaled captured Ottoman officials who refused to be baptized into Christianity.[5][30]

The first battle of Skanderbeg's rebels against the Ottomans was fought on 10 October 1445, on mountain Mokra. According to Setton, after Skanderbeg was allegedly victorious in the Battle of Torvioll, the Hungarians are said to have sung praises about him and urged Skanderbeg to join the alliance of Hungary, the Papacy and Burgundy against the Ottomans.[28] In the spring of 1446, using help of Ragusan diplomats, Skanderbeg requested support from the Pope and Kingdom of Hungary for his struggle against the Ottomans.[31]

War against Venice

Marin Span was commander of Skanderbeg's forces which lost fortress Baleč to Venetian forces in 1448 during Skanderbeg's war against Venice. Marin and his soldiers retreated toward Dagnum after being informed by his relative Peter Span about the large Venetian forces heading toward Baleč.[32]

Treaty of Gaeta

On 26 March 1450 a political treaty was stipulated in Gaeta between Alfonso V for the Kingdom of Naples and Stefan, Bishop of Krujë, and Nikollë de Berguçi, ambassadors of Skanderbeg. In the treaty Skanderbeg would recognize himself a vassal of the Kingdom of Naples, and in return he would have the Kingdom's protection from the Ottoman Empire. After Alfonso signed this treaty with Skanderbeg, he signed similar treaties with other chieftains from Albania: Gjergj Arianiti, Gjin Muzaka, George Stresi Balsha, Peter Spani, Paul Dukagjini, Thopia Muzaka, Peter of Himara, Simon Zanebisha and Karlo Toco. By the end of 1450 Skanderbeg also agreed peace Ottomans and obliged himself to pay tribute to the sultan.[33]

To follow the treaty of Gaeta, Naples sent a detachment of 100 Napolitan soldiers commanded by Bernard Vaquer to the castle of Kruje in the end of May 1451.[34] Vaquer was appointed as special commissioner[35] and took over Kruje on behalf of the Kingdom of Naples and put its garrison under his command.[36]

Aftermath

Ivan Strez Balšić was perceived by Venice as Skanderbeg's successor.[37] After Skanderbeg's death Ivan and his brother Gojko Balšić, together with Leke, Progon and Nicholas Dukagjini, continued to fight for Venice.[38] In 1469 Ivan requested from the Venetian Senate to return him his confiscated property consisting of Castle Petrela, woivodate of "Terra nuova" of Kruje (unknown position), territory between Kruje and Durrës and villages in the region of Bushnesh (today part of the Kodër-Thumanë municipality).[39] Venice largely conceded to the wishes of Ivan Balšić and installed him as Skanderbeg's successor.[40]

See also

References

- Studime Filologjike. Akademia e Shkencave e RPSSH, Instituti i Ghuhesise dje i Letersise. 1972. p. 49.

Vrana Konti me krahun e lidhur dhe Vladan Jurica me kokën e pështjeUur ...

- Kosta Balabanov; Krste Bitoski (1978). Ohrid i Ohridsko niz istorijata. Opštinsko sobranie na grad Ohrid. p. 62.

Скендербег ја исползувал настанатата ситуација, дезертирал од фронтот, решен да подигне општенародно востание во својата област. Планот наполно му успеал, тако што, наскоро, голем дел од Средна Албанија, заедно са пошироката Дебарска област, преминале на раците во устаниците. На таков начин Охридскиот санџак се претворил во поприште на жестоки судари помегу регуларната османска војска и востаниците предводени....

- Schmitt Oliver, "Skanderbeg. Der neue Alexander auf dem Balkan". Verlag Friedrich Pustet, Regensburg, 2009, p. 44.

- Jean W Sedlar (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. University of Washington Press. pp. 393–. ISBN 978-0-295-97291-6.

A rare example of successful Christian resistance to the Turks in the 15th century, although in a fairly remote part of Europe , was provided by Skanderbeg, the Albanian mountain chieftain who became the leader of a national revolt. For over a quarter-century until his death in 1468, he led the Albanians in surprisingly effective guerrilla warfare against the Turkish occupiers.

- II, Pope Pius (1 November 2013). Europe (c.1400-1458). CUA Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-8132-2182-3.

George Skanderbeg, a man of noble birth, received his inheritance. ... fortress of Krujë by stratagem and declared himselfa Christian, going so far as to impale the Ottoman officials who refused to accept baptism; see Fine, LMB, 521–22, 556.

- Elsie, Robert (2005), "Muslim literature", Albanian literature: a short history, London: I.B. Tauris in association with the Centre for Albanian Studies, pp. 33, 34, ISBN 1845110315, retrieved January 18, 2011,

Much legendry has been attached to the name of Scanderbeg...based on embellishments by historian Marinus ... according to legendry, Scanderbeg successfully repulsed thirteen Ottoman incursions, including three major Ottoman sieges of the citadel of Kruja led by the Sultans themselves...In fact, this period was more of an Albanian civil war between rival families, in particular between Skanderbeg and Leke Dukagjini

- Bury, John Bagnell; Whitney, James Pounder; Tanner, Joseph Robson; Charles William Previté-Orton; Zachary Nugent Brooke (1966). The Cambridge Medieval History. Macmillan. p. 383.

In Albania, where rebellion had been smouldering for several years, the heroic Skanderbeg (George Castriota) revolted and under ...

- Fine 1994, p. 535

In 1432 Andrew Thopia revolted against his Ottoman overlords ... inspired other Albanian chiefs, in particular George Arianite (Araniti) ... The revolt spread ... from region of Valona up to Skadar ... At this time, though summoned home by his relatives ... Skanderbeg did nothing, he remained ... loyal to sultan

- Jireček, Konstantin (1923). Istorija Srba. Izdavačka knjižarnica G. Kona. p. 147.

Искусни вођа Арнит (Арианит) поче у средњој Албанији већ у августу 1443 године поново борбу против турака.

- Kenneth M. Setton; Harry W. Hazard; Norman P. Zacour (1 June 1990). A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on Europe. Univ of Wisconsin Press. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-299-10744-4.

One result of the victorious campaign of 1443 was the successful revolt of Albanians under George Castriota

- Fine, John V. A.; Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. University of Michigan Press. p. 548. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

The crusaders' successes inspired two other major revolts, ... the revolt of Skanderbeg in Albania...

- Frasheri, Kristo (2002). Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468. ISBN 99927-1-627-4.

- Frasheri, Kristo (2002). Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468. ISBN 99927-1-627-4.

- Drizari, Nelo (1968). Scanderbeg; his life, correspondence, orations, victories, and philosophy.

- Frasheri, Kristo (2002). Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra, 1405–1468. ISBN 9789992716274.

- Gibbon, Edward (1802). Volume 12. The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. T. Cadell jun. and W. Davies. pp. 168.

- Frasheri, Kristo (2002). Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu: jeta dhe vepra (1405-1468). ISBN 9789992716274.

- Schmitt 2012, p. 55

in seiner Gefolgschaft fanden sich neben Albanern auch Slawen, Griechen und Vlachen.

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (September 2009), Skanderbeg. Der neue Alexander auf dem Balkan (PDF), Verlag Friedrich Pustet, ISBN 978-3-7917-2229-0, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07

- Shukarova, Aneta; Mitko B. Panov; Dragi Georgiev; Krste Bitovski; Ivan Katardziev; Vanche Stojchev; Novica Veljanovski; Todor Chepreganov (2008), Todor Chepreganov (ed.), History of the Macedonian People, Skopje: Institute of National History, p. 133, ISBN 978-9989159244, OCLC 276645834, retrieved 26 December 2011,

deportation of the Archbishop of Ohrid, Dorotei, to Istanbul in 1466, to-gether with other clerks and bolyars who probably were expatriated be-cause of their anti Ottoman acts during the Skender-Bey’s rebellion.

- Judith Herrin (2013). Margins and Metropolis: Authority Across the Byzantine Empire. Princeton University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-691-15301-8.

A revolt against Turkish authority in Albania, led by George Castriota (Iskender Bey or “Skanderbeg”) was successful for a brief period and was supported by dissident Greeks in the Morea.

- Noli, Fan Stylian (1968). Vepra të plota: Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu (1405-1468). Rilindija. p. 138.

...Vladan Jurica, këshilltari i tij më i besueshëm, ...

- Babinger, Franz (1992). Mehmed the Conqueror and His Time. Princeton University Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-691-01078-1.

... a solid military alliance was concluded among all the Albanian and Serbian chieftains along the Adriatic coast from southern Epirus to the Bosnian border.

- "A Timeline of Skanderbeg's Campaigns". Archived from the original on March 28, 2011. Retrieved March 28, 2011.

- Božić 1979, p. 358

Представник млетачких власти, и да je хтео, није био у стању да ce одупре одржавању таквог скупа, као што ни неколико месеци доцније није могао да ce супротстави Скендербеговим људима који су no граду лљачкали стоку и одводили жене и децу.

- Božić 1979, p. 363

Мада ниједан савремени млетачки документ не помиње овај скуп, сви старији и многи новији историчари прихватили су Барлецијеве вести не придајући им, разуме се, исти значај.

- Biçoku, Kasem (2009). Kastriotët në Dardani. Prishtinë: Albanica. pp. 111–116. ISBN 978-9951-8735-4-3.

- Setton p. 73.

- Stojanovski, Aleksandar (1988). Istorija na makedonskiot narod. Makedonska kniga. p. 88.

- (Firm), John Murray (1872). A Handbook for Travellers in Greece: Describing the Ionian Islands, Continental Greece, Athens, and the Peloponnesus, the Islands of the Ægean Sea, Albania, Thessaly, and Macedonia. J. Murray. p. 478.

The names of religion and liberty provoked a general revolt of the Albanians, who indulged the Ottoman garrisons in the choice of martyrdom or baptism ; and for 23 years Skanderbeg resisted the powers of the Turkish Empire, — the hero of ...

- Jovan Radonić (1905). Zapadna Evropa i balkanski narodi prema Turcima u prvoj polovini XV veka. Izd. Matice srpske. p. 249. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

...с пролећа 1946 обраћао за помоћ папи и Угарској преко републике дубровачке...

- Srpska Akademija Nauka i Umetnosti 1980, p. 39: "...да поруше обновљени Балеч с таквим снагама као да је у питању највећа тврђава. То је Петар Спан јавио свом рођаку Марину и овај је у последњем тренутку сакупио војнике и спустио се према Дању".

- Spremić, Momčilo (1968). Zbornik Filozofskog fakulteta. Naučno delo. pp. 253, 254. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

Тај мир је склопљен до краја 1450 јер је Скендербег почетком 1451, када је ступао у вазални однос с напуљским краљем Алфонском Арагонским, већ имао уговор са султаном и плаћао му харач.

- Tibbetts, Jann (30 July 2016). 50 Great Military Leaders of All Time. Vij Books India Pvt Ltd. p. 571. ISBN 978-93-85505-66-9.

Following the Treaty of Gaeta, in the end of May 1451, a small detachment of 100 Catalan soldiers, headed by Bernard Vaquer, was established at the castle of Kruje.

- Gegaj, Athanas (1937). L'Albanie et l'Invasion turque au XVe siècle (in French). Bureaux du Recueil, Bibliothéque de l'Université. p. 88. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

En vertu du traité, Alphonse V envoya en Albanie, au mois de juin 1451, un officier de sa trésorerie, Bernard Vaquer, avec les pouvoirs de commissaire spécial.

- Marinescu, Constantin (1994). La politique orientale d'Alfonse V d'Aragon, roi de Naples (1416-1458). Institut d'Estudis Catalans. pp. 181, 182. ISBN 978-84-7283-276-3.

- Jens Schmitt, Oliver; Konrad Clewing, Edgar Hösch (2005), "Die venezianischen Jahrbücher des Stefano Magno (ÖNB Codd 6215–6217) als Quelle zur albanischen und epirotischen Geschichte im späten Mittelalter (1433–1477)", Südosteuropa : von vormoderner Vielfalt und nationalstaatlicher Vereinheitlichung : Festschrift für Edgar Hösch (in German), Oldenbourg Verlag, p. 167, ISBN 978-3-486-57888-1, OCLC 62309552,

...Ivan Strez Balsics, des von Venedig anerkannten Nachfolgers Skanderbegs,...

- Schmitt 2001, p. 297

die Skanderbegs Personlichkeit gelassen hatte, nicht zu füllen. Deshalb muste Venedig wie in den Jahrzehnten vor Skanderbeg mit einer Vielzahl von Adligen zusammenarbeiten; neben Leka, Progon und Nikola Dukagjin gehörten zu dieser Schicht auch Comino Araniti, wohl derselbe, der 1466 Durazzo überfallen hatte; die Söhne von Juani Stexi, di Johann Balsha, Machthaber zwischen Alessio und Kruja; Gojko Balsha und seine söhne der woiwode Jaran um Kruja (1477), und auch der mit seinem Erbe überforderte Johann Kastriota.

- Jens Schmitt, Oliver; Konrad Clewing, Edgar Hösch (2005), "Die venezianischen Jahrbücher des Stefano Magno (ÖNB Codd 6215–6217) als Quelle zur albanischen und epirotischen Geschichte im späten Mittelalter (1433–1477)", Südosteuropa : von vormoderner Vielfalt und nationalstaatlicher Vereinheitlichung : Festschrift für Edgar Hösch (in German), Oldenbourg Verlag, p. 168, ISBN 978-3-486-57888-1, OCLC 62309552,

Ivan Strez Balsa, ein Neffe Skanderbegs, verlangte dabei seinen enteigneten Besitz zurück, und zwar die Burg Petrela, das nicht weiter zu lokalisierende Woiwodat von „Terra nuova" um Kruja (kaum gemeint sein kann das ebenfalls als Terra nuova bezeichnete osmanische Elbasan), die Dörfer des Gebietes von „Bonese" (Bushnesh, WNW von Kruja gelegen), schließlich das Land zwischen Kruja und Durazzo.

- Jens Schmitt, Oliver; Konrad Clewing, Edgar Hösch (2005), "Die venezianischen Jahrbücher des Stefano Magno (ÖNB Codd 6215–6217) als Quelle zur albanischen und epirotischen Geschichte im späten Mittelalter (1433–1477)", Südosteuropa : von vormoderner Vielfalt und nationalstaatlicher Vereinheitlichung : Festschrift für Edgar Hösch (in German), Oldenbourg Verlag, p. 168, ISBN 978-3-486-57888-1, OCLC 62309552,

Tatsächlich kam Venedig den Wünschen Ivan Strezs weitgehend entgegen und setzte ihn damit zum Nachfolger Skanderbegs ein. [Venice largely conceded to the wishes of Ivan Strezs and installed him as Scanderbeg's successor]

Sources

- Schmitt, Oliver Jens (2012), Die Albaner: eine Geschichte zwischen Orient und Okzident (in German), C.H.Beck, ISBN 978-3-406-63031-6CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Setton, Kenneth Meyer (1978), The Papacy and the Levant, 1204–1571, DIANE Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87169-127-9

- Božić, Ivan (1979). Nemirno pomorje XV veka (in Serbian). Belgrade: Srpska književna zadruga. OCLC 5845972. Retrieved 12 February 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Srpska Akademija Nauka i Umetnosti (1980). Glas (Volumes 319–323) (in Serbian). Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Science and Arts.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)