Silver Reef, Utah

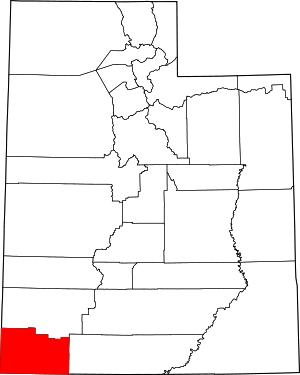

Silver Reef is a ghost town in Washington County, Utah, United States, about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of St. George and 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Leeds. Silver Reef was established after John Kemple, a prospector from Nevada, discovered a vein of silver in a sandstone formation in 1866. At first, geologists were uncertain about Kemple's find because silver is not usually found in sandstone. In 1875, two bankers from Salt Lake City sent William Barbee to the site to stake mining claims. He staked 21 claims,[2] and an influx of miners came to work Barbee's claims and to stake their own. To accommodate the miners, Barbee established a town called Bonanza City. Property values there were high, so several miners settled on a ridge to the north of it and named their settlement Rockpile.[3] The town was renamed Silver Reef after silver mines in nearby Pioche closed and businessmen arrived.

Silver Reef | |

|---|---|

Silver Reef in the 1880s | |

Silver Reef Location of Silver Reef in Utah | |

| Coordinates: 37°15′10″N 113°22′4″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| County | Washington |

| Founded | 1875 |

| Abandoned | 1891 |

| Named for | Silver in sandstone formations |

| Elevation | 3,796 ft (1,157 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1445602[1] = |

By 1879, about 2,000 people were living in Silver Reef. The town had a mile-long Main Street with many businesses, among them a Wells Fargo office, the Rice Building, and the Cosmopolitan Restaurant. Although adjacent to many settlements with a majority of Mormon residents, the town never had a meeting house for Latter-day Saints, only a Catholic church. In 1879, a fire destroyed several businesses, but the residents rebuilt them. Mines were gradually closed, most of them by 1884, as the worldwide price of silver dropped.[4] By 1901, most of the buildings in town had either been demolished or moved to Leeds.

In 1916, mining operations in Silver Reef resumed under the direction of Alex Colbath, who organized the area's mines into the Silver Reef Consolidated Mining Company. These mines were purchased by American Smelting and Refining Company in 1928, but the company did minimal work as a result of the Great Depression. The Western Gold & Uranium Corporation purchased Silver Reef's mines in 1948, and in 1951, they began mining uranium in the area. These operations did not last long either, and the Western Gold & Uranium Corporation sold their mines to the 5M Corporation in 1979. Today, the Wells Fargo office, the Cosmopolitan Restaurant, the Rice Building, and numerous foundations and walls remain in the town site, and a few dozen homes have been constructed in the area. Silver Reef has been absorbed by the neighboring community of Leeds.

Geology and geography

The sandstone formations from which Silver Reef gets its name were formed when tectonic stresses forced long, longitudinally aligned sections of Navajo Sandstone to buckle and stand on their sides, giving them the appearance of ocean reefs.[5] Over long periods of time silver ore, sediments, and vegetation were carried in water runoff from the Chinle Formation to the White, Buckeye, and East reefs. The ore settled as deposits and the vegetation became petrified.[6] The Silver Reef Mining District's geologic resources consist mainly of silver deposits, with smaller deposits of copper, gold, lead, and uranium oxide.[7][8] Iron oxide deposits in the soil rocks cause a red coloration, and dinosaur tracks from the early Jurassic period have been found in the area.[9]

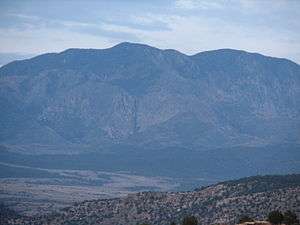

Silver Reef is close to the western border of the Colorado Plateau and about 15 miles (24 km) northeast of St. George and 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Leeds. Dixie National Forest, Leeds Creek, the White Reef, and the Pine Valley Mountain Wilderness lie directly west of Silver Reef. The Pine Valley Mountain Wilderness has sage steppe, mountain brush, pinyon pine, coniferous trees, and ponderosa pine.[10] Interstate 15 and Toquerville are 1 mile (1.6 km) and 4 miles (6.4 km) east of Silver Reef, respectively. Pintura is 9.5 miles (15.3 km) north of Silver Reef, and Quail Creek State Park, the ghost town of Harrisburg, the Buckeye Reef, and Red Cliffs Recreation Area are south of Silver Reef. The elevation of Red Cliffs Recreation Area is between 2,000 feet (610 m) and 3,000 feet (910 m).[9]

Climate

Silver Reef is located in one of the driest and hottest parts of the state of Utah; summer temperatures often rise above 100 °F (38 °C). Temperatures of 50 °F (10 °C) or above can occur during the winter, but nighttime winter temperatures occasionally drop below 0 °F (−18 °C). Silver Reef receives about 12 inches (30 cm) of precipitation annually. It is not unusual to see an inch or more of snow in the winter. July has the warmest average temperature, 99 °F (37 °C), and December is coldest, with an average temperature of 53 °F (12 °C). The highest recorded temperature was 114 °F (46 °C), in July 2001, and the lowest recorded temperature was −2 °F (−19 °C), in January 1963.[11]

| Climate data for Silver Reef, Utah | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 74 (23) |

80 (27) |

93 (34) |

97 (36) |

106 (41) |

111 (44) |

114 (46) |

111 (44) |

107 (42) |

97 (36) |

85 (29) |

74 (23) |

114 (46) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 53 (12) |

60 (16) |

66 (19) |

75 (24) |

84 (29) |

94 (34) |

99 (37) |

97 (36) |

90 (32) |

78 (26) |

63 (17) |

54 (12) |

76 (25) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 27 (−3) |

32 (0) |

38 (3) |

43 (6) |

51 (11) |

59 (15) |

65 (18) |

64 (18) |

56 (13) |

45 (7) |

33 (1) |

27 (−3) |

45 (7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

2 (−17) |

10 (−12) |

21 (−6) |

23 (−5) |

34 (1) |

46 (8) |

39 (4) |

31 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

12 (−11) |

1 (−17) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.56 (40) |

1.59 (40) |

1.78 (45) |

0.78 (20) |

0.55 (14) |

0.28 (7.1) |

0.71 (18) |

1.10 (28) |

0.88 (22) |

0.94 (24) |

1.08 (27) |

0.77 (20) |

12.02 (305) |

| Source: weather.com[11] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 1,046 | — | |

| 1890 | 177 | −83.1% | |

| 1990 | 50 | — | |

| Source: Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns[12] | |||

Silver Reef was first settled in 1875; by the 1880 Census, 1,046 people were living there,[13] and a local census taken in 1884 gave a population of 1,500.[12] By 1890, after most of the mines had closed, the population had dropped to 177,[13] and by 1900, only lessees of the mines were living there.[14] In 1916, Alex Colbath organized the Silver Reef Consolidated Mining Company.[8] Several miners moved in to work for Colbath,[15] who lived in the town with his wife, Mayme, until the 1950s.[16] After the Colbaths' departure, Silver Reef was completely abandoned. Subdivision of the land, planned in the 1960s, was finalized by 1980.[17] During the Census of 1990, 50 people lived in Silver Reef, and today Silver Reef is considered a part of Leeds.[12]

History

The Silver Reef area was first inhabited by Anasazi Native Americans between about 200 AD and 1300 AD. The Anasazi were nomads who followed the migration of the animals they hunted, typically deer, mountain sheep, elk, and jackrabbits.[18] They were also farmers and gardeners, growing corn, wheat, rye, and barley.[19] Many were potters, and pottery can be found in abandoned villages.[20] The Anasazi usually constructed temporary dwellings out of sticks and leaves, often using bark for the roofs. Occasionally they built more permanent dwellings out of rocks, usually along the side of a mountain, often large enough to accommodate several families. Storage pits were often placed behind the rock dwellings. Settlements were typically small, as food was scarce.[21] A group of Virgin Anasazi lived in what is now the Red Cliffs Anasazi Site in Red Cliffs Recreation Area.[9]

Silver was discovered in the area in the 1860s. One commonly accepted story is that a prospector named John Kemple came to the area in 1866 from Montana. While staying at the home of Orson B. Adams in the settlement of Harrisburg,[22] Kemple decided to do some prospecting, and soon located a vein of silver a few hundred yards southwest of the home.[23] He did not find enough ore to interest him, so he left for Nevada. Five years later, Kemple returned to the Silver Reef area, staked a few mining claims, and organized them under the Union Mining District. The Union Mining District was abandoned, but in 1874, Kemple returned with a group of miners, reorganized the claims under the Harrisburg Mining District, and began developing a mine.[23] Kemple later became discouraged with his claims and sold them.[24]

According to a less accepted story, a man known as "Metalliferous" Murphy, an assayer from Pioche, Nevada, was brought a piece of a grindstone made of sandstone from the Silver Reef area by miners in Pioche. After performing tests on the sample, Murphy stated that it contained over $200 of silver per ton. After some investigation, Murphy discovered that the samples had come from the area that was to become Silver Reef. There is no record of Murphy ever staking a claim, but he did allegedly attract the attention of miners.[25]

Geologists and other miners refused at first to believe the news that silver had been found in sandstone. When brought an actual sample from the area, the Smithsonian Institution called it an "interesting fake".[4] In 1875, news of the silver discovery reached the Walker brothers, well-known bankers from Salt Lake City. They hired William T. Barbee, who had previously staked mining claims in Ophir,[26] to stake claims on their behalf. He staked 21 claims and published an article on the claims in The Salt Lake Tribune. In the article, Barbee mentioned that the area had "an abundance of rich silver mines".[27] This set off a silver rush,[26] and by late 1875, Barbee had established a town called Bonanza City. Several businessmen then came into the area, inflating property values. Many miners and businessmen looking for inexpensive land set up a tent city north of Bonanza City and called it "Rockpile".[3] When the mines in nearby Pioche were closed in November 1875, many of the miners and business owners who had worked there came into the area of "Rockpile" in what is known as the "Pioche Silver Stampede",[28] and the name of the settlement was changed to Silver Reef. As construction of the St. George LDS Temple ended in mid-1877, labor opportunities for the workers became available in Silver Reef. Pine Valley Mills and Mount Trumbull in the Arizona Strip supplied most of the lumber used to construct the buildings. During its first year, Silver Reef did not have a smelter; as a result, the silver ore mined in Silver Reef was taken to Pioche and Salt Lake City for smelting.[26]

Immediately following the initial silver rush, a town site was platted and the town was built. The first permanent business building established in Silver Reef was a store at the intersection of the roads from the Buckeye, White, and East reefs.[29] By 1878, the town's business district consisted of a hotel, boarding houses, nine stores, six saloons, five restaurants, a bank, two dance halls, a newspaper called The Silver Echo (which later became the Silver Reef Miner),[30] and eight dry goods stores. Two cemeteries, one Catholic and one Protestant, were located south of Silver Reef's business district.[25] Most of the businesses in Silver Reef were situated along a mile-long Main Street.[31] The mining district consisted of 37 mines and five stamp mills: the Christy, Stormont, Leeds, Buckeye and Barbee & Walker mills.[6][32] Although it was surrounded by settlements with large Mormon populations, the town never had a Mormon meeting house. A Catholic church was the only church located within the town.[33] After the First Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869, many of the Chinese workers who had been hired to build it were out of work. Some returned to China, but others remained in Utah. A group of 250 of these workers set up a Chinatown in a level area just south of Silver Reef.[4] Silver Reef's Chinatown had a Chinese mayor and several businesses.[25] By 1879, Silver Reef's population had reached 2,000, and the town also had a horse race track, a brewery, and a brass band.[34] Shooting matches among members of the Silver Reef Rifle Club and sometimes residents of nearby towns took place on the horse race track.[35]

Although most of the residents of Silver Reef were not Mormon, they had good relations with residents of the nearby Mormon settlements.[36] A lot of the cotton and other agricultural items produced in the area were transported by wagon to Silver Reef. Many of the town's buildings were constructed by Mormon labor workers. Reverend Lawrence Scanlan was invited to say Mass in the St. George Tabernacle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints before the Catholic church in Silver Reef was constructed.[37] To assist Scanlan, the Mormon choir learned Latin chants.[25] When politics were involved, however, these good relations were forgotten. Most Mormons were members of the People's Party, and most people in Silver Reef were members of the Liberal Party. As Silver Reef grew, the townspeople wanted to change the county seat of Washington County from St. George to Silver Reef. This alarmed the members of the People's Party, the main figures in the territorial legislature. The legislature moved the county line eastward in 1882; this maintained the People's Party majority in Washington County by transferring such Mormon farming communities as Grafton, Rockville, and Springdale from Kane County to Washington County.[25]

Although it had good relations with other towns, Silver Reef had the usual labor disputes between mining camp wage laborers and mine owners.[38] After a major dispute with the Stormont Mining Company,[39] the Silver Reef Miners Union was formed to support wages.[40][41] Gambling, prostitution, and shootouts were also commonplace.[29] One shootout involved Town Marshal Johnny Diamond and mine guard Jack Truby. Tensions between Diamond and Truby temporarily shut down the Kinner mine. Truby was hired by Colonel Enos Wall, foreman and owner of the Kinner, to guard the mine until told otherwise. Diamond went to the Kinner mine to serve the closure warrant, but Truby refused to allow Diamond into the mine, and forced Diamond to leave the property immediately.[42]

The gunfight started during court proceedings in the back room of a saloon. Diamond and Truby argued about Truby wearing his hat inside, and continued the argument outside. When Diamond asked for Truby's gun, Truby shot at Diamond, Diamond returned fire, and both men died. An inquest on both men, held in the saloon, found that the bodies each contained bullet wounds from the .41 caliber revolvers that were used, and powder burns caused by the proximity of the shootout.[42][43] Truby also had .45 caliber bullet wounds in his back, indicating that somebody else had shot him during the shootout.[44]

Another shootout occurred between Henry Clark and Sykes Griffen on December 1, 1878, at Cassidy's Silver Reef Saloon. Although it is not known exactly what happened, it is believed that Griffen, a faro dealer at the saloon, and Clark, a regular patron, had previously argued over gambling matters. The shooting began when Griffen argued with Clark about a bet they had made. After arguing for several minutes, Griffen pulled a pistol on Clark and shot him. Several witnesses said that Clark pulled a pistol on Griffen and shot him, while other witnesses said that after Clark was shot, other patrons in the saloon, including Clark's father, beat and shot Griffen.[45]

Another instance of murder occurred on October 3, 1880, when Thomas Forrest stabbed Michael Carbis. Carbis, the foreman of the California mine, had fired Forrest the day before on account of his violent nature.[46] The murder occurred near the Buckeye boarding house. Forrest initially had a pistol, but he put it away and drew a knife instead when he got within a few feet of Carbis. Carbis died soon after the stab wound was inflicted.[47] Silver Reef's residents were angered by the murder and soon lynch threats were delivered. Forrest, who had been arrested soon after the murder had been committed, was transferred to the jail in St. George for his own safety. Prior to the moving of Forrest, a lynch mob gathered and followed the sheriff's escort to the St. George jail. Once there, they overpowered the sheriff, took Forrest out of his cell, and tried to hang him on a telegraph pole. When the pole broke, they took him to a cottonwood tree and hanged him there.[46] The residents of St. George were shocked at the sight of Forrest's hanging, and one man was reputed to have said, "I have observed that tree growing there for the last 25 years. This is the first time I have ever seen it bearing fruit."[48]

Decline

On May 30, 1879, fire was discovered under a restaurant. Hundreds of Silver Reef's residents threw buckets of water from nearby Leeds Creek on the fire and put wet blankets on the adjacent business buildings, but the fire spread to the Harrison House Hotel, one of the town's most prominent buildings. The fire destroyed several other businesses along Main Street before it was finally extinguished. The Salt Lake Tribune reported that Silver Reef had been "Chicagoed", and that a state of panic was felt even after the fire had been extinguished.[49][50]

Silver Reef's residents rebuilt the businesses that had been destroyed, but the town soon began to decline. In 1881, the Stormont Mining Company and the Barbee & Walker Mining Company had to decrease wages from $4 per day to $3.50 per day in all of their mines except the Savage mine (a Stormont property). In response to the decrease in wages, the Silver Reef Miners Union was formed. In February 1881, union members began talking about striking the mines, and as word of this potential strike spread, the Stormont Mining Company discharged those of its miners who were part of the Miners Union. In response, the discharged union members escorted the company's superintendent, Washington Allen, out of Silver Reef. Allen immediately went to the Second District Court in Beaver and filed a lawsuit against the union members.[51] Before they went to court, the union members held a meeting and decided to shut down the Savage mine. Led by Matthew O'Loughlin, the president of the Silver Reef Miners Union, they walked through Silver Reef in rows of two, and, upon arriving at the Savage mine, O'Loughlin and nine other men went into the hoisting works and ordered the engineer on duty to shut down the pumps that kept water from the water table out of the mine. After the pumps were shut down, the group of ten went into the Savage mine and ordered everyone out.[39]

A few days later, the sheriff of St. George, accompanied by a posse of 30 men,[51] arrested 25 members of the Miners Union,[25] including Matthew O'Loughlin.[39] As Silver Reef's jail was too small to hold all 25 prisoners, most of them were jailed in the Rice Building. The Rice Building could not hold all of the prisoners, so a line was drawn around the building, and anyone who crossed the line was threatened with shooting. The Miners Union members were transferred to Beaver, where they were tried for riot, conspiracy, and false imprisonment. Thirteen of the members were sentenced to imprisonment; three were bailed out, while ten were sent to the Utah Territorial Penitentiary. Matthew O'Loughlin was sentenced to twenty days in prison and was charged a $75 fine.[51]

A few years after the strike, the world's silver market dropped, causing the foreclosure of many of the mines. To compensate for the drop in prices, the mines' stockholders reduced the wages of the miners.[52] Instead of striking again, the miners accepted this. In addition, the miners inadvertently dug below the water table, and the mine shafts began filling with water faster than it could be pumped out.[52] By 1884, most of the mines were idle or closed; the last was officially closed in 1891,[4] although lessees of the mines continued to operate them past that year.[14] Many merchants went bankrupt and left town. The Silver Reef mines produced about $8 million worth of silver ore.[24][26] Between 1891 and 1901, another $250,000 worth was mined.[25] Several people attempted to restart mining operations in 1898, 1909, 1916, and 1950, but none of these attempts were successful.[3][53] After Silver Reef's mines were closed, many of the buildings were purchased for their lumber and building stone. One buyer dismantled the building he bought and discovered $10,000 in gold coins. News of the find spread quickly, and most of the buildings in Silver Reef were demolished in hopes of discovering more gold, but none was found.[25]

The Silver Reef Consolidated Mining Company was organized in 1916 by Alex Colbath, who owned most of the area's mines.[54] In 1928, American Smelting and Refining Company purchased its mines, and in 1929 they sank a three-compartment shaft on the White Reef. This new mine was connected with the flooded Savage mine, and the water was pumped out. Minimal work was done after that, however, as there was not enough ore to keep the operation profitable during the Great Depression.[8] Ownership of the mines was then passed back to Alex Colbath, but in 1948 the Western Gold and Uranium Corporation purchased the claims from Colbath,[55] and in 1951 they mined the sandstone for uranium oxide deposits. The first shipment of uranium oxide came from the Ann's Pride mine,[8] and in total, 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) of uranium oxide was shipped out of the region. The claims were bought in 1979 by the 5M Corporation, but the company did not operate in Silver Reef for long.[56]

Tourism and popular culture

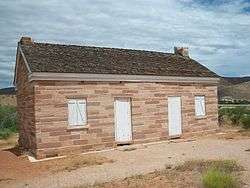

Following the closure of the district's mines, the Wells Fargo office was used as a residence by Alex and Mayme Colbath until the 1950s.[57] It was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 11, 1971,[58] and currently serves as an art gallery and a museum. The Rice Building burned down, and was rebuilt in 1991. The Cosmopolitan Restaurant was reconstructed to appear as it did in the 19th century, and it served European cuisine until it was closed in 2010.[59][60] There are many remnants of houses and other buildings, and there are also markers indicating where some buildings once stood, such as the Elk Horn Saloon. Some of the area has been preserved for its history.

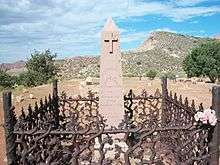

Behind the Wells Fargo office is a powder house which, as of 2011, contains models of the town, the town's major mills, and its Catholic church.[61] The Catholic and Protestant cemeteries were restored by the Leeds Lion's Club in 1998 and can be visited.[62][63] Several other original buildings remain, including the Clancy Market, McCormick Store, the two-story Harrison House Hotel,[64] and some of the mining buildings. Main Street, once a mile long, is now only a few hundred yards long and is surrounded by private homes.[55]

Besides exploring the ghost town, visitors can explore the red rock country surrounding Silver Reef. Backpacking, camping, fishing, mountain biking, birdwatching, and hunting are among the activities available.[65][66] Visitors to Red Cliffs Recreation Area, located south of Silver Reef, can picnic in a designated area with cottonwood trees. A half-mile hiking trail leads to the Red Cliffs Anasazi Site, the remains of an Anasazi habitation. The 6-mile (9.7 km) Red Reef Trail leads to the Cottonwood Wilderness Study Area. Dinosaur footprints that date back to the early Jurassic period can be found in the area,[9] and the Orson Adams House in nearby Harrisburg allows visitors to study the pioneer history of Washington County.[22]

Silver Reef has appeared in American films since the late 1960s. The area was scouted by corporate executives from Twentieth-Century Fox for use in the 1969 film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and served as a backdrop in the 1979 film The Electric Horseman.[67] Silver Reef was featured in the 1998 documentary Treasure House: The Utah Mining Story.[68]

References

- USGS, Silver Reef.

- Federal Writers' Project 1945, p. 301.

- Anderson 1994, p. 498.

- Massey & Wilson 2006, pp. 43–44.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 53.

- Powell 2003, p. 281.

- Bugden 1993, pp. 19–20.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 193–194.

- US BLM, Red Cliffs Recreation Area.

- Wilderness.net, Pine Valley Mountains Wilderness.

- Weather Channel, Leeds, Utah.

- Moffat 1996, p. 310.

- U.S. Census Bureau.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 159–191.

- Beal 1987, p. 1.

- Murbarger 1950, p. 6.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 194–198.

- Marriott 1996, pp. 27–38.

- Marriott 1996, pp. 39–43.

- Hurst, Utah History Encyclopedia.

- Marriott 1996, pp. 12–15.

- Washington County Historical Society, Orson Adams Home.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 27–34.

- Poll 1989, p. 222.

- Carr 1972, pp. 138–142.

- Alder & Brooks 1996, pp. 168–172.

- Barbee 1875.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 39.

- DeJauregui 1988, pp. 142–144.

- Morton 1906, p. 337.

- Beal 1987, p. 5.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 81–86.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 87–90.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 112.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 141.

- Patterson 1998, p. 3.

- Richardson 1992, p. 267.

- Clements 2003, p. 104.

- Utah Supreme Court 1884, p. 145.

- Wyman 1979, p. 157.

- Enyeart 2009, pp. 43–50.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 135.

- Beckstead 1991.

- Beal 1987, p. 9.

- Washington County Historical Society, Saloon Shootout Leaves Two Dead.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 133–134.

- Deseret News, October 6, 1880.

- Florin 1971, p. 392.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, p. 123.

- Salt Lake Tribune, June 4, 1879.

- Proctor & Shirts 1991, pp. 151–154.

- Huff & Wharton 1997, p. 106.

- Scholl, Camoin & Roylance 1982, pp. 644–645.

- Beal 1987, p. 17.

- Beal 1987, p. 19.

- Ege 2005, p. 34.

- Murbarger 1950, p. 5.

- Washington County Historical Society, Wells Fargo.

- Dammeron Valley Landowners Association, Leeds; Silver Reef Utah.

- Google maps, Cosmopolitan Restaurant.

- Washington County Historical Society, Silver Reef Museum.

- Beal 1987, pp. 20–22.

- Washington County Historical Society, Silver Reef Cemeteries.

- Speck 2000.

- Bromka 1999, pp. 354–358.

- McIvor 1998, pp. 263–265.

- D'Arc 2010, pp. 102–110.

- Treasure House: The Utah Mining Story 1998.

- Works cited

- Alder, Douglas D.; Brooks, Karl F. (1996). A history of Washington County: from isolation to destination. Utah centennial county history series. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah State Historical Society. ISBN 0-913738-13-1. OCLC 35394589.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anderson, Bart C. (1994). Utah History Encyclopedia. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-425-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beal, Wilma (1987). My Story of Silver Reef. St. George, Utah: Heritage Press. OCLC 33478865.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckstead, James (1991). Cowboying: A Tough Job In A Hard Land. University of Utah publications in the American West, v. 27. Salt Lake City, Utah: University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-378-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bromka, Gregg (1999). Mountain Biking Utah. Helena, Montana: Falcon. ISBN 978-1-56044-824-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bugden, Miriam (1993). Geologic Resources of Washington County, Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Geological Survey. ISBN 1-55791-353-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carr, Stephen (1972). The Historical Guide to Utah's Ghost Towns. Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics. ISBN 978-0-914740-30-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clements, Eric L. (2003). After the Boom in Tombstone and Jerome, Arizona. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 0-87417-571-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood Came to Town: The History of Moviemaking in Utah (1st ed.). Layton, UT: Gibbs Smith. ISBN 1-4236-0587-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeJauregui, Ruth E. (1988). Ghost Towns. New York, New York: Bison Books Corp. ISBN 0-517-65844-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ege, Carl L. (2005). Selected Mining Districts of Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Geological Survey. ISBN 1-55791-726-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enyeart, John P. (2009). The Quest for "Just and Pure Law": Rocky Mountain Workers and American Social Democracy, 1870–1924. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. pp. 43–50. ISBN 978-0-8047-4986-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Federal Writers' Project (1945). Utah: A Guide to the State. New York: Hastings House. OCLC 479998451.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Florin, Lambert (1971). Ghost Towns of the West. New York: Promontory Press. ISBN 0883940132.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Huff, Paula; Wharton, Tom (1997). Hiking Utah's Summits. Helena, MT: Falcon Publishing. ISBN 1-56044-588-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marriott, Alice (1996). Indians of the Four Corners: The Anasazi and Their Pueblo Descendants. New York: Crowell Publishings. ISBN 0-941270-91-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Massey, Peter; Wilson, Jeanne (2006). Backcountry Adventures Utah. Spokane, Washington: Adler Publishing. ISBN 1-930193-27-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McIvor, D. E. (1998). Birding Utah. Guilford, CT: Pequot. ISBN 1-56044-615-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moffat, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-3033-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morton, J. Sterling (1906). Illustrated History of Nebraska, Volume 2. Lincoln, NE: Jacob North & Company. OCLC 11455764.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Patterson, Richard M. (1998). Butch Cassidy: A Biography. Omaha, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8756-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Poll, Richard D. (1989). Utah's History. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. ISBN 0-87421-142-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Powell, Allan Kent (2003). The Utah Guide (3rd ed.). Golden, CO: Fulcrum. ISBN 1-55591-114-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Proctor, Paul Dean; Shirts, Morris A. (1991). Silver, Sinners and Saints: A History of Old Silver Reef, Utah. Gainesville, Florida: Paulmar, Inc. ISBN 0-9625042-1-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Richardson, Frank D. (1992). Rowley Family Histories. Fruit Height, Utah: Story Work Publishers. ISBN 0-9748137-4-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scholl, Barry; Camoin, François André; Roylance, Ward J. (1982). Utah: A Guide to the State. Salt Lake City, Utah: Utah Arts Council. ISBN 0-87905-836-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Utah Supreme Court (1884). "People v. O'Loughlin". Reports of cases decided in the Supreme Court of the state of Utah, Volume 3. San Francisco: A. L. Bancroft. pp. 133–151. OCLC 291093069.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wyman, Mark (1979). Hard Rock Epic: Western Miners and the Industrial Revolution, 1860–1910. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06803-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Online references

- Ames, Ed (narrator), Groberg, Lee (producer) (1998). Treasure House: The Utah Mining Story (Television production). Salt Lake City, Utah: BWE Video. ISBN 1-57742-228-7. OCLC 39738744. Archived from the original on 2011-09-11. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- Barbee, William T. (December 19, 1875). "Southern Utah". Utah Digital Newspapers. Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 2011-09-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bureau of Land Management (03-04-2011). "Red Cliffs Recreation Area". blm.gov. US Department of the Interior. Archived from the original on 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2011-08-22. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Cold Blooded Murder". Deseret News. October 6, 1880. Retrieved 2012-06-24.

- Dammeron Valley Landowners Association. "Leeds — Silver Reef Utah". mydvla.org/dvla/. Dammeron Valley Landowners Association. Archived from the original on 2011-08-22. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- Google. "Cosmopolitan Restaurant". maps.Google.com. Google. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- Hurst, Winston. "Anasazi". Utah History Encyclopedia. Utah History to Go. Retrieved 2011-08-30.

- Jay (June 4, 1879). "Silver Reef Fire". The Salt Lake Tribune. Retrieved 2011-08-19.

- Murbarger, Nell (1950). "Buckboard Days at Silver Reef". The Desert Magazine. Palm Desert, California: Desert Press. 13 (5): 4–9. ISSN 0011-9237. OCLC 228665202. Retrieved 2011-08-25.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Silver Reef". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2011-09-17.

- Speck, Gary B. (February 1, 2000). "Silver Reef, Utah". Ancestry.com. Ghost Town USA. Retrieved 2011-02-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- U.S. Census Bureau. "Decennials — Census of Population and Housing". census.gov. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2006-02-08. Retrieved 2011-08-25.

- Washington County Historical Society. "Orson B. Adams Home". wchsutah.org. Washington County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2011-09-02. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- Washington County Historical Society (1997). "Saloon Shootout Leaves Two Dead" (PDF). wchsutah.org. Washington County Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- Washington County Historical Society. "Wells Fargo Express Office". wchsutah.org. Washington County Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- Washington County Historical Society. "Silver Reef Museum". wchsutah.org. Washington County Historical Society. Retrieved 2011-08-31.

- Washington County Historical Society. "Silver Reef Catholic Cemetery in Silver Reef, Utah". wchsutah.org. Washington County Historical Society. Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- Weather Channel. "Monthly Averages for Leeds, Utah (Silver Reef)". Weather.com. The Weather Channel. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

- Wilderness.net. "Pine Valley Mountain Wilderness". Wilderness.net. Retrieved 2011-09-12.

Further reading

- Eckman, Anne (2002). History of Washington County. Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers. OCLC 52206962.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mariger, Marietta (1952). Saga of Three Towns, Harrisburg, Leeds, Silver Reef. Panguitch, Utah: Garfield County News. OCLC 228784421.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stucki, Alfred (1966). A historical study of Silver Reef : Southern Utah Mining Town. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University. Dept. of History Brigham Young University. OCLC 289770565.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Florin, Lambert (1971). Ghost Towns of the West. Superior Publishing Company and Promontory Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Silver Reef, Utah. |

- Silver Reef at Washington County Historical Society

- Silver Reef at GhostTownGallery.com

- Silver Reef at GhostTowns.com

- Silver Reef at LegendsofAmerica.com

- Historical Silver Reef, Utah!