Grafton, Utah

Grafton is a ghost town, just south of Zion National Park in Washington County, Utah, United States. Said to be the most photographed ghost town in the West, it has been featured as a location in several films, including 1929's In Old Arizona—the first talkie filmed outdoors—and the classic Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid.[2] The nearest inhabited town is Rockville.

Grafton | |

|---|---|

The schoolhouse at Grafton. Built in 1886, it was also used as a church and public meeting place. | |

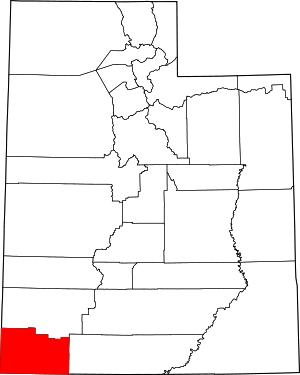

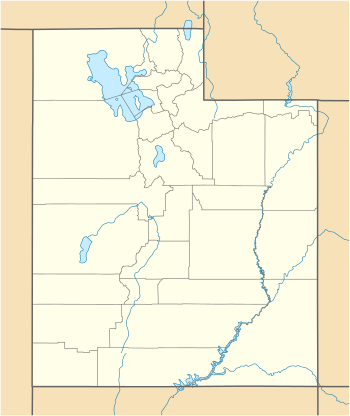

Grafton Location of Grafton in Utah  Grafton Grafton (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 37°10′02″N 113°04′48″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Utah |

| County | Washington |

| Established | 1859 |

| Abandoned | 1921 |

| Named for | Grafton, Massachusetts |

| Elevation | 3,665 ft (1,117 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 1437570[1] |

.jpg)

History

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1870 | 38 | — | |

| 1880 | 71 | 86.8% | |

| 1890 | 104 | 46.5% | |

| 1900 | 98 | −5.8% | |

| 1910 | 106 | 8.2% | |

| 1920 | 46 | −56.6% | |

| 1930 | 23 | −50.0% | |

The site was first settled in December 1859 as part of a southern Utah cotton-growing project ordered by Brigham Young (see Utah's Dixie). A group from Virgin led by Nathan Tenney established a new settlement they called Wheeler. Wheeler didn't last long; it was largely destroyed on the night of January 8, 1862 by a weeks-long flood of the Virgin River, part of the Great Flood of 1862.[3] The rebuilt town, about a mile upriver, was named New Grafton, after Grafton, Massachusetts.[2]

The town grew quickly in its first few years. There were some 28 families by 1864, each farming about an acre (0.4 hectare) of land.[4] The community also dug irrigation canals and planted orchards, some of which still exist. Grafton was briefly the county seat of Kane County, from January 1866 to January 12, 1867,[5] but changes to county boundaries in 1882 placed it in Washington County.[6]

Flooding was not the only major problem. One particular challenge to farming was the large amounts of silt in Grafton's section of the Virgin River. Residents had to dredge out clogged irrigation ditches at least weekly, much more often than in most other settlements. Grafton was also relatively isolated from neighboring towns, being the only community in the area located on the south bank of the river. In 1866, when the outbreak of the Black Hawk War caused widespread fear of Indian attacks, the town was completely evacuated to Rockville.[4]

Continued severe flooding discouraged resettlement, and most of the population moved permanently to more accessible locations on the other side of the river. By 1890 only four families remained. The end of the town is usually traced to 1921, when the local branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was discontinued.[7] The last residents left Grafton in 1944.

A United Press news item dated May 23, 1946, stated that the town was purchased by movie producer Harry Sherman as a film location site. He bought it from William Russell, 80, a descendant of the co-founder, and one the town's three current inhabitants.[8]

Restoration

In June 1997, the Grafton Heritage Partnership was organized to protect, preserve, and restore the Grafton Townsite. With cooperation from former Grafton residents, the Utah State Historical Society, the BLM, the Utah Division of State History, and others, the old church, Russell Home, Louisa Foster Home, the Berry fence in the cemetery, and John Wood home were restored, with new windows, doors, roofing and other structural enhancements to represent the period in which they were built. In addition, 150 acres (61 ha) of farmland were purchased, on which agricultural operations are performed to enhance the farming appearance. The site is under 24-hour surveillance. The partnership is currently looking for a live-in caretaker to oversee the preservation of the townsite.[9]

See also

- Duncan's Retreat, Utah, a nearby ghost town

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Grafton

- Thompson, George A. (November 1982). Some Dreams Die: Utah's Ghost Towns and Lost Treasures. Salt Lake City, Utah: Dream Garden Press. pp. 28–29. ISBN 0-942688-01-5.

- Reid, H. Lorenzo (1964). Dixie of the Desert. Zion National Park: Zion Natural History Association. pp. 107–108. ASIN B000Q7IG9Y.

- Carr, Stephen L. (1986) [June 1972]. The Historical Guide to Utah Ghost Towns (3rd ed.). Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics. pp. 133–134. ISBN 0-914740-30-X.

- Bradley, Martha Sonntag (January 1999). A History of Kane County (PDF). Utah Centennial County History Series. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society. p. 59. ISBN 0-913738-40-9. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- Bradley, p.100.

- Alder, Douglas D.; Brooks, Karl F. (1996). A History of Washington County: From Isolation to Destination (PDF). Utah Centennial County History Series. Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society. p. 81. ISBN 0-913738-13-1. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- United Press, "Utah Town Purchased As Film Location Site", The San Bernardino Daily Sun, San Bernardino, California, Friday 24 May 1946, Volume 52, page 2.

- "Grafton Heritage Partnership". Grafton Heritage Partnership. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

Further reading

- Askar, Jamshid (24 October 2009). "Remembering Grafton". Church News. pp. 8–10. Retrieved November 20, 2009.

- Platt, Lyman and Karen (1998). Grafton, Ghost Town on the Rio Virgin. St. George, Utah: The Grafton Heritage Partnership.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grafton, Utah. |

- Grafton Heritage Organization

- Grafton, Washington County, Utah at the Washington County UTGenWeb site

- Grafton, Utah on GhostTownGallery.com