Siege of the International Legations

The Siege of the International Legations occurred in 1900 in Peking, the capital of the Qing Empire, during the Boxer Rebellion. Menaced by the Boxers, an anti-Christian, anti-foreign peasant movement, 900 soldiers, marines, and civilians, largely from Europe, Japan, and the United States, and about 2,800 Chinese Christians took refuge in the Peking Legation Quarter. The Qing government took the side of the Boxers. The foreigners and Chinese Christians in the Legation Quarter survived a 55-day siege by the Qing Army and Boxers. The siege was broken by an international military force which marched from the coast of China, defeated the Qing army, and occupied Peking (now known as Beijing). The siege was called by the New York Sun "the most exciting episode ever known to civilization."[1]

Legation Quarter

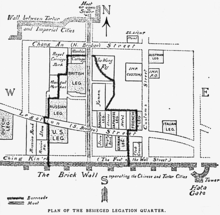

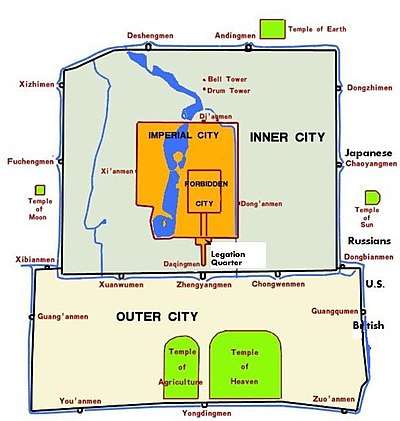

The Legation Quarter was approximately 2 mi (3.2 km) long and 1 mi (1.6 km) wide. It was located in the area of the city designated by the Qing government for foreign legations. In 1900, there were 11 legations located in the quarter as well as a number of foreign businesses and banks. Ethnic Chinese-occupied houses and businesses were also scattered about the quarter. The 12 or so Christian missionary organizations in Beijing were not located in the Legation Quarter, but rather dispersed around the city. In total, there were about 500 citizens of Western countries and Japan residing in the city. The northern end of the Legation quarter was near the Imperial City where the Empress Dowager Cixi resided. The southern end was bounded by the massive Tartar Wall which ringed the entire city of Beijing.[2] The eastern and western ends were major streets.

Rising tensions

By 1900 the great powers had been chipping away at Chinese sovereignty for 60 years. They had forced China to allow the import of opium, which caused widespread addiction; defeated China in several wars; asserted a right to promote Christianity; and imposed unequal treaties under which foreigners and foreign companies in China were accorded special privileges and immunities from Chinese law. Thus the Qing or Manchu dynasty that had ruled China for more than two centuries was crumbling, and Chinese culture was under religious and secular assault by a powerful alien culture.[3]

Boxer movement

Authorities differ as to the origin of the Boxers, but they became prominent in Shantung (Shandong) in 1898 and spread northward toward Beijing. They were an indigenous peasant movement, related to the secret societies that had flourished in China for centuries—and which, on occasion, had threatened Chinese central governments. The Boxers were named—probably by American missionary Arthur H. Smith—for their acrobatic rituals which included martial arts, twirling swords, prayers and incantations.[4] Similar to other anti-Western millenarianism movements around the world, such as the Ghost Dance in the US, the Boxers believed that with the proper ritual they would become invulnerable to Western bullets. The religious and magical practices of the Boxers had "as a paramount goal the affording of protection and emotional security in the face of a future... that was fraught with danger and risk."[5] The Boxers had no central organization but appear to have been organized on the village level. They were anti-foreign and anti-missionary. Their slogan was "Support the Qing! Destroy the Foreigner!".[6] Initially feared as a possible threat by the Chinese government, they slowly gained the support of influential politicians in Beijing, who saw the Boxers as a movement that could be used to eliminate foreign influence in China.

Boxers attack Christians

In early 1900 the Boxer movement spread rapidly north from Shandong into the countryside near Beijing. Boxers burned Christian churches, killed Chinese Christians and intimidated Chinese officials who stood in their way. Two missionaries, Protestant William Scott Ament and Catholic Bishop Favier, reported to the diplomatic ministers (Ambassadors) about the growing threat.[7][8] American Minister Edwin H. Conger cabled Washington, "The whole country is swarming with hungry, discontented, hopeless idlers." Requesting a warship to be stationed offshore of Tianjin, the nearest port to Beijing, he reported, "Situation becoming serious."[9] On May 30, the diplomats, led by British Minister Claude Maxwell MacDonald, requested that foreign soldiers come to Beijing to defend the legations and the citizens of their countries. The Chinese government reluctantly acquiesced, and the next day more than 400 soldiers from eight countries disembarked from warships and traveled by train to Beijing from Tianjin. They set up defensive perimeters around their respective missions.[10][11]

On June 5 the railroad line to Tianjin was cut by Boxers in the countryside and Beijing was isolated. On June 13 a Japanese diplomat, Sugiyama Akira, was murdered by soldiers of Gen. Dong Fuxiang and that same day the first Boxer, dressed in his finery, was seen in the Legation Quarter. The German Minister, Clemens von Ketteler, and German soldiers captured a Boxer boy and inexplicably executed him.[12] In response, that afternoon thousands of Boxers burst into the walled city of Beijing and burned most of the Christian churches and cathedrals in the city, killing many Chinese Christians and several Catholic priests. The Chinese Christians were accused of collaborating with the foreigners.[13] American and British missionaries and their converts had taken refuge in the Methodist Mission and an attack there was repulsed by American Marines. Soldiers at the British embassy and German legations shot and killed several Boxers.[14]

Dilemma of the Chinese Government

In mid-June the Chinese government was still indecisive about the Boxers. Some officials—Ronglu, for example—counseled the Empress Dowager that the Boxers were "rabble" who would be easily defeated by foreign soldiers.[15] On the other side of the question were anti-foreign officials who advised cooperation with the Boxers. "The Court appears to be in a dilemma," said Sir Robert Hart. "If the Boxers are not suppressed, the Legations threaten to take action—if the attempt to suppress them is made, this intensely patriotic organization will be converted into an anti-dynastic movement."[16] The event that irrevocably pushed the Chinese government to the side of the Boxers was the attack by foreign warships on the Dagu forts on June 17. The attack was made to try to maintain communications with Tianjin and aid an army under the command of Adm. Edward Seymour in its attempt to march to Beijing during the Seymour Expedition and reinforce the Legations.[17]

On June 19 the Empress Dowager sent a diplomatic note to each of the legations in Beijing informing them of the attack on Dagu and ordering all foreigners to depart Beijing for Tianjin within 24 hours. Otherwise, said the note, "China will find it a difficult matter to give complete protection."[18] Upon receipt of the note, the diplomats convened and agreed it would be suicidal to leave the Legation Quarter and travel to the coast in an unfriendly countryside. The next morning, June 20, Baron von Ketteler, the German Minister, proposed to take up the matter with the Zongli Yamen, the Chinese Foreign Ministry, but he was murdered by a Manchu officer, Capt. En Hai of the Hushenying, while en route to the meeting.[19] With this, the Ministers informed all their citizens in Beijing to take refuge in the Legation Quarter.[20] Thus began the 55-day siege.[21]

Besieged

The British, American, French, German, Japanese, and Russian military guards each took responsibility for the defense of their respective legations. The Austrians and Italians abandoned their isolated legations. The Austrians joined the French and the Italians collaborated with the Japanese. The Japanese and Italian force established defense lines in the Fu – a large mansion and park where most of the estimated 2,812 Chinese Christians taking refuge were housed. The American and German Marines held positions on the Tartar Wall behind their legations. The 409 guards had the job of defending a line that snaked through 2,176 yd (1,990 m) of urban terrain.[22] The great majority of foreign civilians took refuge in the British Embassy, the largest and most defensible of the diplomatic legations. A census of civilians counted 473 people: 245 men, 149 women, and 79 children. About 150 of the men volunteered to participate, to a greater or lesser extent, in the defense. The civilians included at least 19 nationalities of which British and Americans were the most numerous. Large numbers of Chinese Christians were conscripted for labor, especially for building barricades.[23]

The British Minister Claude MacDonald was selected as the commander of the defense and Herbert G. Squiers, an American diplomat, became his chief of staff. The guards of the different countries, however, operated semi-independently and MacDonald could only suggest, not order, coordinated action.[24] The guards were not well armed. Only the American Marines had sufficient ammunition. The defenders had three machine guns. The Italians had a small cannon. Fortunately, an old cannon barrel and ammunition was found in the Legation Quarter and from it a serviceable artillery piece was constructed that the Americans called "Betsy" and others called "the International".[25]

The foreigners ransacked the Legation Quarter for food and other supplies. Food and water were adequate, although the foreigners without private food stocks subsisted on a steady diet of horsemeat and musty rice. However, the Chinese Christians, especially the Catholics, had a much harder time of it and by the end of the siege were starving. The Protestant missionaries took care of their converts, but the Chinese Catholics were mostly neglected.[26] Medical supplies were scarce but a sizeable number of doctors and nurses, mostly missionaries, were present.[27]

American missionaries took over management of most necessities for life in the Legation Quarter, including food, water, sanitation, and health. MacDonald’s most important appointment was Methodist Missionary Frank Gamewell as chief of the Fortifications Committee. Gamewell and his crew of "fighting parsons" were universally acclaimed for their defensive works surrounding the British Legation.[28]

About three miles distant from the Legation Quarter a similar siege took place at the Beitang or North Cathedral of the Roman Catholic Church. Thirty-three priests and nuns, 43 French and Italian soldiers, and more than 3,000 Chinese Christians held off the Chinese army and Boxers. There was no communication during the siege between the Beitang and the Legation Quarter.

Chinese attacks and resolve

For several days after June 20—the official beginning of the siege—neither the foreigners inside the Legation Quarter nor the Chinese soldiers outside it had any coherent plan for defense or attack. The number of Chinese soldiers ringing the legations is uncertain, but certainly numbered in the thousands. On the west were the Gansu Muslim soldiers of Dong Fuxiang[29] and on the east were units of the Peking Field Army. The overall commander of the Chinese forces was Ronglu—who was anti-Boxer and disapproved of the siege.[30] Chinese policy equivocated between belligerence and conciliation during the 55-day siege. Several attempts by Ronglu to effect a cease-fire failed because of suspicions and misunderstandings on both sides.[31]

The Chinese first attempted to extinguish the foreigners in the Legation Quarter by fire. For several days at the beginning of the siege they set fires in the buildings around the British Legation. On June 23, most of the buildings of the Hanlin Academy, the national library of China, and its books, many irreplaceable, burned. Both sides blamed the other for its destruction.[32] The Chinese Army then turned its attention to the Fu, the refuge for most of the Chinese Christians, and the domain of Lt. Col. Goro Shiba, the most admired military officer in the siege. Shiba, with his small group of Japanese soldiers, mounted a skillful defense against the Chinese who advanced behind walls built ever-closer to the Japanese, gradually threatening to surround them in a vise-like grip. British soldiers were often detailed to reinforce the Japanese during attacks and all admired Shiba's work.[33] The most desperate fighting took place near the French Legation, where 78 French and Austrians and 17 volunteers were under assault in convoluted urban terrain, in which the front lines were only 50 ft (15 m) from each other. The French also feared that Chinese sappers were digging tunnels for mines beneath their positions.[34]

The Germans and the Americans occupied perhaps the most crucial of all defensive positions: the Tartar Wall. Holding the top of the 45 ft (14 m) tall and 40 ft (12 m) wide Wall was vital. If it fell to the Chinese, they would have an unobstructed field of fire into the Legation Quarter. The German barricades faced east on top of the wall and 400 yd (370 m) west were the west-facing American positions. The Chinese advanced toward both positions by building barricades ever-closer. It was a claustrophobic existence for the soldiers on the wall. "The men all feel they are in a trap," said the American commander, Capt. John T. Myers, "and simply await the hour of execution."[35] Added to the daily advances of the Chinese were the nightly serenades of rifle and artillery fire and firecrackers designed to keep the foreigners awake and alert. "From June 20 to July 17 we had nightly attacks," said a missionary woman. American Minister Conger said "that some of them, for furious firing, exceeded anything he experienced in the American Civil War."[36] The hard-pressed Legation guards saw their numbers diminish daily with casualties.

The Chinese were divided on the prosecution of the siege. The anti-Boxer faction, headed by Rong Lu, and the anti-foreign faction, headed by Prince Duan, squabbled at the Chinese court. Cixi, the Dowager Empress, vacillated between the two. She declared a truce for negotiations on June 25, but it endured only a few hours. She declared a cease-fire on July 17 which lasted for most of the remainder of the siege. As a sign of good will, she sent food and supplies to the foreigners.[37] The disagreements among the Chinese occasionally resulted in altercations and violence between Boxers and soldiers and between different units of the Imperial army.[38]

Fight on the Wall

The most critical threat to the survival of the foreigners came in early July. On June 30 the Chinese forced the Germans off the Tartar Wall, leaving the American Marines alone in its defense. At the same time a Chinese barricade advanced to within a few feet of the American positions and it became clear that the Americans had to abandon the wall or force the Chinese to retreat. At 2:00 am on July 3 the foreigners launched an assault against the Chinese barricade on the wall with 26 British, 15 Russian and 15 Americans under the command of American Capt. John T. Myers. As hoped, the attack caught the Chinese sleeping; about 20 of them were killed and the survivors expelled from the barricades. Two American Marines were killed and Capt. Myers was wounded and spent the rest of the siege in the hospital.[39] The capture of Chinese positions on the Wall was hailed as the "pivot of our destiny" by one of the besieged. The Chinese did not attempt to regain or advance their positions on the Tartar Wall for the remainder of the siege.[40]

Darkest days and a truce

Sir Claude MacDonald said July 13 was the "most harassing day" of the siege.[41] The Japanese and Italians in the Fu were driven back to their last defense line. While the Fu was under heavy attack the Chinese detonated a mine beneath the French Legation, destroying most of it, killing two soldiers and pushing the French and Austrians out of most of the French Legation. Frank Gamewell began digging bombproof shelters as a last refuge for the besieged. The end seemed near.[42]

The next day, however, a conciliatory message was received from the Chinese, which raised hopes—dashed again on July 16 when the most capable British officer was killed and journalist George Ernest Morrison was wounded.[43] However, American Minister Conger carried on a communication with the Chinese government and on July 17 firing died down on both sides and an armistice began.[44]

It was just in time; more than one-third of the legation guards were dead or wounded. The motivation on the Chinese side was probably the realization that an allied force of 20,000 men had landed in China and retribution for the Boxers and the siege was at hand.

Relief of the Legations

On July 28 the foreigners in the Legation Quarter received their first message from the outside world in more than a month. A Chinese boy—a student of the missionary William Scott Ament—sneaked into the Legation Quarter with the news that a rescue army of the Eight-Nation Alliance was in Tianjin 100 mi (160 km) away and would advance shortly to Beijing. The news was hardly reassuring, as the besieged had been expecting an earlier rescue.[45] The Chinese government also passed along inquiries about the welfare of the besieged from their governments. A British soldier suggested that an appropriate reply would be, "Not massacred yet."[46]

After many relatively quiet days, the night of August 13, with the rescue army just 5 mi (8.0 km) outside the gates of Beijing, may have been the most difficult of the siege.[47] The Chinese broke the truce with an artillery barrage of the British Legation and heavy fire in the Fu. However, the Chinese confined themselves to firing from a distance rather than mounting an assault until, at 2:00 am on August 14, the defenders heard from the east the sound of a machine gun, a sign that the rescue army was on the way. At 5:00 am came the sound of artillery outside the walls of Beijing.[48]

Five national contingents advanced on the walls of Beijing on August 14: British, American, Japanese, Russian and French. Each had a gate in the Wall for its objective. The Japanese and Russians were delayed at their gates by Chinese resistance. The small French contingent got lost. The Americans scaled the walls rather than attempting to force their way through a fortified gate. However, it was the British who won the race to relieve the siege of the legations. They entered the city through an unguarded gate and proceeded with virtually no opposition.[49] At 3:00 pm the British passed through a drainage ditch—the "water gate"—under the Tartar Wall. Sikh and Rajput soldiers from India and their British officers had the honor of being the first to enter the Legation Quarter.[50] The Chinese armies ringing the legation quarter melted away. A short time later the British commander, Gen. Alfred Gaselee, entered and was greeted by Sir Claude MacDonald dressed in "immaculate tennis flannels" and a crowd of cheering ladies in party dresses.[51] The American troops, under Gen. Adna Chaffee, arrived at 5:00 pm.[52] The commanding Muslim general, Ma Fulu, and four cousins of his were killed in action against the foreign forces. After the battle was over, the Chinese Muslim forces guarded the Empress Dowager Cixi when she fled to Xi'an with the entire Imperial Court; general Ma Fuxiang assisted in guarding Cixi.[53]

Casualties

The foreigners were united in declaring the miraculous nature of their survival. "I seek in vain some military reason for the failure of the Chinese to exterminate the foreigners," said an American military officer.[54] Missionary Arthur Smith summed up the Chinese military performance. "Upon unnumbered occasions, had they been ready to make a sacrifice of a few hundred lives, they could have extinguished the defence [of the Legation Quarter] in an hour." However, the equivocation on the part of the Chinese to use their military assets decisively against the Legation Quarter does not deny the fact that soldiers on both sides fought and died in large numbers. The foreign soldiers defending the Legation Quarter suffered heavy casualties. Of the 409 soldiers, 55 were killed and 135 wounded, a casualty rate of 46.5%. In addition, 13 civilians were killed and 24 wounded, mostly men who participated in the defence.[55]

A small Japanese force of one officer and 24 sailors commanded by Col. Shiba distinguished itself defending the Fu and the Chinese Christians there. It suffered greater than 100% casualties. This was possible because many of the Japanese troops were wounded, entered into the casualty lists, then returned to the line of battle only to be wounded once more and again entered in the casualty lists. The French force of 57 men also suffered more than 100% casualties.[56]

Chinese military casualties are not known, nor were deaths among the Chinese Christians in the Legation Quarter recorded.

Propaganda

During the siege Sheng Xuanhuai and other provincial officials suggested the Qing court give Li Hongzhang full diplomatic power to negotiate with foreign powers. Li Hongzhang telegraphed back to Sheng Xuanhuai on June 25, describing the war declaration a "false edict" (luanming). Later, the "Southeast Mutual Protection" was reached by provincial officials as a consensus not to follow Empress Cixi’s declaration of war.[57] Li Hongzhang also totally refused to listen to orders from the government for more troops when they were needed to fight against the foreigners, which he had available, derailing the Chinese war effort.[58]

Li Hongzhang used the siege as a political weapon against his rivals in Beijing, since he controlled the Chinese telegraph service; he exaggerated and lied, claiming that Chinese forces committed atrocities and murder upon the foreigners and exterminated all of them. This information was sent to the Western world. He aimed to infuriate the Europeans against the Chinese forces in Beijing, and succeeded in spreading massive amounts of false information to the West. This false information spread by Li played a part in the massive atrocities which the foreigners later committed upon the Chinese in Beijing.[59][60] For refusing to obey the Chinese government's orders and not sending his own troops to help the Chinese army at all during the Boxer Rebellion, Li Hongzhang was praised by the Westerners.[61] For his role in the Siege of the International Legations, he is criticized by the PRC official history[62], which has only recently begun to allow different interpretations through popular media such as TV series aired by the official CCTV.[63][64][65]

Aftermath

The Empress Dowager and her court fled Beijing on August 15. She remained in exile in Shanxi province until 1902, when she was permitted by the foreign armies occupying Beijing to return to reoccupy the throne.[66] For China, the Boxer Rebellion was a disaster but turned out, ironically, about so well as could be expected. China remained together as a single country, while prior to the Boxer Rebellion it seemed likely to be divided by the colonial powers. The Chinese government supported the Boxers, who otherwise might have turned anti-Qing and hastened the extinction of the dynasty, but was unsuccessful in killing the foreigners in the Legations. Had the Chinese succeeded, retribution from the Western nations and Japan might have been more severe. Ronglu later took credit for saving the besieged: “I was able to avert the crowning misfortune which would have resulted from the killing of the Foreign Ministers”. Ronglu was being disingenuous, as his forces came very close to breaking the ability of the besieged to resist.[31]

The Boxer movement disintegrated during the siege. Some Boxers were incorporated into the army but, probably, most returned to their homes in the countryside where they became targets for punitive expeditions by the foreign military forces occupying Beijing after the siege.[67]

The military occupation of Beijing and much of northern China became an orgy of looting and violence in which foreign soldiers, diplomats, missionaries, and journalists participated.[68] Reports of the behaviour of the foreigners in Beijing caused widespread criticism in Western countries, including from Mark Twain. While the rescue of the besieged foreigners in the Legation Quarter was seen as a proof of the superiority of Western civilization, the sordid aftermath of the siege may have contributed to many people in the United States and Europe reëvaluating the morality of forcing Western culture and religion on the Chinese.[69]

See also

- Qing Dynasty Royal Decree on events leading to the signing of Boxer Protocol

References

Citations

- Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009, pp. 1, 83–5

- Thompson, 29–39.

- Thompson, pp. 7–8.

- O’Connor, Richard. The Spirit Soldiers: A Historical Narrative of the Boxer Rebellion. New York: Putnams, 1973, p. 20.

- Cohen, Paul (2007), Bickers, Robert; Tiedemann, RG (eds.), The Boxers, China, and the World, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, pp. 183, 192.

- Cohen, Paul A. History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York: Columbia U Press, 1997.

- Porter, Henry D. William Scott Ament: Missionary of the American Board to China. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1911, pp. 175–9.

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1900, p. 130

- Foreign Relations of the United States, 1900, Washington: GPO, pp. 122, 130.

- Morrison, Dr. George E. "The Siege of the Peking Legations" The Living Age, Nov 17, 24 and Dec 1, 8, and 15, 1900, p.475.

- Thompson, 42.

- Weale, B. L. (Bertram Lenox Simpson), Indiscreet Letters from Peking. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1907, pp. 50–1.

- Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military. WW Norton & Company. p. 70. ISBN 0-393-04085-2. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

provocations by foreigners.

- Morrison, p. 270

- Der Ling, Princess. Two Years in the Forbidden City. New York: Moffat, Yard, 1911, p.. 161

- Seagrave, Sterling. Dragon Lady: the Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China. New York: Vantage, 1992, p. 318

- Fleming, Peter. The Siege at Peking. New York: Harper, 1959, pp. 80–83

- Davids, Jules, ed. American Diplomatic and State Papers: The United States and China: Boxer Uprising. Series 3, Vol. 5, Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1981, p. 83

- Franciszek Przetacznik (1983). Protection of officials of foreign states according to international law. BRILL. p. 229. ISBN 90-247-2721-9. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Smith, Arthur H. China in Convulsion. 2 Vols. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1901, pp. 243–255

- "Imperial Decree on Day Nineteen of May (lunar calendar)". En.wikisource.org. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Ingram, James H., M.D. "The Defense of the Legations in Peking I". The Independent. Dec 13, 1900, p. 2979-2984., Ingram, James H., M.D. "The Defense of the Legations in Peking II". The Independent. Dec 20, 1900, p. 2035-40.

- Thompson, 83–85, 88–89

- Fleming, p. 118

- Allen, Rev. Roland The Siege of the Peking Legations. London: Smith, Elder, 1901, 187

- Allen, 256; Fenn, Rev. Courtnay Hughes, "The American Marines in the Siege of Peking". The Independent. Dec 6, 2000. pp. 2919–2920

- Ransome, Jessie. The Story of the Siege Hospital. London: SPCK, 1901.

- Weale, 142–143; Smith, 743–747

- Michael Dillon (December 16, 2013). China's Muslim Hui Community: Migration, Settlement and Sects. Routledge. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-1-136-80933-0.

- Fleming, pp. 127, 226–8.

- Fleming, pp. 228–9

- Smith, Boxer Rebellion, 1900, Historik Orders, pp. 282–3, retrieved September 30, 2010.

- Weale, 126

- Weale, 130

- Myers, pp. 542–50.

- Mateer, Ada Haven. Siege Days: Personal Experiences of American Women and Children during the Peking Siege. Chicago: Fleming H. Revell, 1903, p. 216

- Benjamin R. Beede (1994). The War of 1898, and U.S. Interventions, 1898–1934: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 50. ISBN 0-8240-5624-8. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Frank Moore Colby; Harry Thurston Peck; Edward Lathrop Engle (1901). The International Year Book: A ompendium of the world's progress during the year 1898–1902. Dodd, Mead & company. p. 207. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Oliphant, Nigel, A Diary of the Siege of the Legations in Peking. London: Longman, Greens, 1901, pp 78–80

- Martin, W.A.P. The Siege in Peking. New York:Fleming H. Revell, 1900, p. 83

- Fleming, 157

- Allen, 204; "The Fortification of Peking during the Siege". The Gospel in all Lands. Feb 1902, 83

- Thompson, Peter and Macklin, Robert The Man who Died Twice: The Life and Adventures of Morrison of Peking. Crow’s Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2005, pp 190–191

- Conger, Sarah Pike, Letters from China. Chicago: A.C McClurg, 1910, p. 135

- Morrison, p. 645

- Miner, Luella, "A Prison in Peking: The Diary of an American Woman during the Siege". The Outlook, Nov. 10, 17, 24, 1900, p. 735

- Lynch, George. "Vae Victis! The Allies in Peking after the Siege". The Independent. Nov 8, 1900, pp. 130–3.

- Allen, 276

- Fleming, 208

- Thompson, 174–182

- Fleming, 203

- Conger, 161

- Jonathan Neaman Lipman (2004). Familiar Strangers: A history of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 169. ISBN 0-295-97644-6. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- Annual Reports of the War Department, 1901, p. 456.

- Myers, 552, with minor corrections

- Fleming, pp. 143–144.

- Zhou, Yongming (June 2005). Historicizing Online Politics: Telegraphy, the Internet, and Political Participation in China. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 75. ISBN 0804751285.

- Marina Warner (1974). The Dragon Empress: Life and Times of Tz'u-hsi, 1835–1908, Empress Dowager of China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Cardinal. p. 138. ISBN 0-351-18657-3. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

moored unmolested in the Chinese port; friendly exchanes took place for a few weeks; in Peking, the court, breathing war, was hampered by its generals, and by Li hung-chang in particular, who simply did not obey and send the reinforcements Tz'u-hsi ordered to the troublespot

- Robert B. Edgerton (1997). Warriors of the Rising Sun: A History of the Japanese Military. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 86. ISBN 0-393-04085-2. Retrieved November 28, 2010.

li hung-chang ownership of the chinese telegraph.

- https://otik.uk.zcu.cz/bitstream/handle/11025/17656/Kocvar.pdf?sequence=1 p. 146

- Herbert Henry Gowen (1917). An Outline History of China (New and Revised ed.). BOSTON: Sherman, French & company. p. 325. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

But for the strong stand taken by some of the Viceroys, notably Chang Chih-tung, Yuan Shih-kai, Liu K'un-i, Tuan Fang and Li Hung-chang, the bloodshed would doubtless have been a thousandfold worse. Happily there were men in China at this crisis who were prepared to take the consequences of disobeying the Dowager

- Archived May 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "历史的当代性阐释——评《走向共和》中的李鸿章形象". Cnki.com. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "李鸿章的新闻观". Cnki.com. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "李鸿章是中国近代"背黑锅"冠军". Cnki.com. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Preston, Diana. The Boxer Rebellion. New York: Berkley Books, 1999

- Thompson, pp. 198–199

- Thompson, 194–204

- Thompson, 194–204.

Sources

- Allen, Rev. Roland The Siege of the Peking Legations. London: Smith, Elder, 1901

- Annual Reports of the War Department, 1901 Washington: Government Printing Office, 1901

- Bickers, Robert and Tiedemann, R.G., The Boxers, China, and the World. Lanham, MD; Rowman and Littlefield, 2007

- Chester M. Biggs (2003). The United States marines in North China, 1894–1942. McFarland. p. 25. ISBN 0-7864-1488-X. Retrieved June 28, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Boot, Max (2003). The savage wars of peace: small wars and the rise of American power. Da Capo Press. p. 428. ISBN 0-465-00721-X. Retrieved June 28, 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cohen, Paul A. History in Three Keys: The Boxers as Event, Experience, and Myth. New York: Columbia U Press, 1997

- Conger, Sarah Pike, Letters from China. Chicago: A.C McClurg, 1910

- Davids, Jules, ed. American Diplomatic and State Papers: The United States and China: Boxer Uprising. Series 3, Vol. 5, Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources, 1981

- Der Ling, Princess. Two Years in the Forbidden City. New York: Moffat, Yard, 1911

- Fenn, Rev. Courtnay Hughes, "The American Marines in the Siege of Peking". The Independent. Dec 6, 2000

- Fleming, Peter. The Siege at Peking. New York: Harper, 1959

- Foreign Relations of the United States, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900

- Ingram, James H., M.D. "The Defense of the Legations in Peking I". The Independent. Dec 13, 1900, p. 2979-2984.

- Ingram, James H., M.D. "The Defense of the Legations in Peking II". The Independent. Dec 20, 1900, p. 2035-40.

- Lynch, George. "Vae Victis! The Allies in Peking after the Siege". The Independent. Nov 8, 1900

- Martin, W.A.P. The Siege in Peking. New York:Fleming H. Revell, 1900

- Mateer, Ada Haven. Siege Days: Personal Experiences of American Women and Children during the Peking Siege. Chicago: Fleming H. Revell, 1903

- Miner, Luella, "A Prison in Peking: The Diary of an American Woman during the Siege". The Outlook, Nov. 10, 17, 24, 1900

- Morrison, Dr. George E. "The Siege of the Peking Legations" The Living Age, Nov 17, 24 and Dec 1, 8, and 15, 1900*

- Myers, Capt. John T. "Military Operations and Defenses of the Siege of Peking". Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute September, 1902

- O'Connor, Richard. The Spirit Soldiers: A Historical Narrative of the Boxer Rebellion. New York: Putnams, 1973

- Oliphant, Nigel, A Diary of the Siege of the Legations in Peking. London: Longman, Greens, 1901

- Porter, Henry D. William Scott Ament: Missionary of the American Board to China. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1911

- Preston, Diana. The Boxer Rebellion. New York: Berkley Books, 1999

- Ransome, Jessie. The Story of the Siege Hospital. London: SPCK, 1901

- Seagrave, Sterling. Dragon Lady: the Life and Legend of the Last Empress of China. New York: Vantage, 1992

- Smith, Arthur H. China in Convulsion. 2 Vols. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1901

- "The Fortification of Peking during the Siege". The Gospel in all Lands. Feb 1902

- Thompson, Larry Clinton. William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion: Heroism, Hubris, and the Ideal Missionary. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009.

- Thompson, Peter and Macklin, Robert The Man who Died Twice: The Life and Adventures of Morrison of Peking. Crow’s Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin, 2005

- Weale, B. L. (Bertram Lenox Simpson), Indiscreet Letters from Peking. New York: Dodd, Mead, 1907