Boxers (group)

The Boxers, also known by various other names in both Chinese and English (see Names), was a Chinese secret society known for having triggered the Boxer Rebellion from 1899 to 1901. It became a massive movement, counting anywhere between 50,000 and 100,000 members. Though the group originally supported the downfall of the Qing leadership of China for being "westernized", the group would later support the ruling Empress Dowager to try and eliminate groups the Boxers opposed, including Christians, Europeans, Caucasians, Japanese, "Western" Chinese, and others who were determined to be detrimental to their efforts, at certain points including other secret societies. The group was all but destroyed by the end of the Boxer Rebellion, with most of its leadership and structure eliminated, though some of its former members continued their actions in various other groups across China.

| Boxers | |

|---|---|

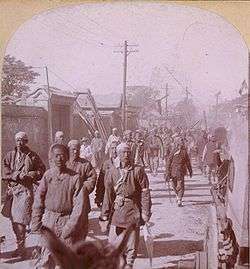

Captured Boxer soldiers during the Boxer Rebellion in Tianjin (1901) | |

| Active | mid-1880s (restructured 1899)–September 1901 |

| Country | |

| Allegiance | |

| Size | 50,000–100,000 |

| Motto(s) | "Kill the foreigners! Slaughter the followers of the foreign devils!"[1] |

| Equipment | Spears, halberds |

| Engagements | Boxer Rebellion |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders | Cao Futian Zhang Decheng |

Names

In the English speaking world, the society is mainly known as the Boxers, due to its members' practice of Chinese martial arts, at the time called "Chinese boxing".[2][3] Though the group had existed since the mid-1880s in China, it was first reported officially as the National Righteousness Group (Chinese: 義民会; pinyin: Yìmínhuì; Wade–Giles: I-Min Hui) in an 1899 Qing report intent on solving disturbances in the Shandong and Zhili Provinces.[4] This is later clarified in a follow-up report to have been a mistake, and that the actual name is in fact the League of Harmony and Justice (Chinese: 義和團; pinyin: Yìhétuán; Wade–Giles: I-Ho T'uan). During 1898, the group was known as the Plum Blossom Fists (Chinese: 梅花拳; pinyin: Méihuāquán; Wade–Giles: Mei-Hua Ch'üan), though this name would not be used into 1899 and after however.[5] In more recent English publications, the name of the group from 1899, Fists of Harmony and Justice (Chinese: 義和拳; pinyin: Yìhéquán; Wade–Giles: I-Ho Ch'üan) or the Society of Righteous Harmonious Fists[6] tends to be used over the yìhétuán based name. The group is also sometimes known in English by any one of its Chinese names, with more recent publications tending to use Pinyin, and older publications using Wade–Giles or other systems.[7]

Origins

During the rule of the Qing dynasty within China, there was often significant influence and force from non-state secret societies, such as the Big Swords Society or the White Lotus Society. These groups often took advantage, through armed members, of the lack of imperial order in many areas of China, along with rampant corruption that enabled the societies to function even in well-controlled areas.

Yi-he boxing, as it was later practised by the Fists of Harmony and Justice, long predated the movement. In 1779, the Qing government already investigated rumours according to which a man named Yang practised this martial arts style in Guan County, Shandong, though state authorities were unable to confirm this at the time.[8]

Though the Boxer movement would originate in Shandong and Hebei intent on lessening governmental influence throughout China by means of violence, the group would quickly include its directive to attempt to eliminate all foreign influence also, which was considered at the time to have already penetrated the imperial government. The group at this time was deeply associated with other secret societies in their efforts to eliminate Christians, as can be seen in the 4 July 1896 with attacks on German missionaries in the regions of Western Shandong that later were controlled by the Boxers.[5]

The Boxer movement first began in these areas in the mid-1880s as various group with similar aims, led by local influences such as Zhang Decheng in Hebei, and Zhu Hongdeng in Shandong, both leading small but devoted groups directly under their personal control. These small groups served as local enforcers of the Boxers' efforts to control the populace, to curtail the influence of both the Qing government and that of foreigners, particularly Christians.

During 1898, the previously separate Boxer groups in Shandong and Hebei would fall under much more direct leadership, with the establishment of structure into the group in the form of ranks. This would also involve the renaming of the group into the "Plum Blossom Fists". However, the name-change was not used past 1898, with the name "Fists of Harmony and Justice" used instead.[5]

On 23 May 1898, an investigation was made by the Guangxu Emperor into disturbances in the Shandong-Zhili border region by a supposed "National Righteousness Group", with the possibility of 10,000 Boxer soldiers being under group command in this region. A representative of the monarchy, Zhang Rumei, would be sent along with an army to put down any unrest in the region. The result of the meeting was not negative, with Zhang reporting that there was no trouble in the region, along with more accurate reports on the group's smaller numbers.

The movement was composed of illiterate people. First and foremost peasants, to which were added idle youth, ruined artisans, and laid off workers.[9] Some Boxer recruits were disbanded imperial soldiers and local militiamen.[10]

Conflict

In March 1898, the Boxers started to agitate the population in the streets with the slogan "Uphold the Qing, destroy foreigners!". Their main leader was Cao FuTian.[2] Other leaders in Zhili Province were Liu Chengxiang, and Zhang Decheng.

After a battle with the Imperial troops in October 1899, the Boxers focused mainly on missionaries and Christian activities, as they were considered "tainting the purity of the Chinese culture". The Qing government was divided towards how to react to the Boxer's activities. The conservative element of the court was in favour of them. Prince Duan, a fervent supporter of their cause, arranged a meeting between Cao and Empress Dowager Ci Xi.[11] At the meeting, the crown prince even wore a Boxer uniform to show support.[12]

At the beginning of June 1900, about 450 men of the Eight-Nation Alliance arrived in Beijing to protect the foreign legations under siege by the Boxers and Imperial Army, in what was the Siege of the International Legations. The Boxers were at their peak, now supported by some elements of the Imperial Army. They changed their slogan to "Support the Qing, destroy foreigners!".[13]

The Boxers multiplied their murderous actions against foreigners and Chinese Christians. In Beijing, the Boxers were officially placed under command of members of the Court, such as Prince Duan. During the Rebellion, the Boxers, fighting troops of the Eight-Nation Alliance with close combat weapons or even their own hands, were decimated. After the conflict, The Empress Dowager Ci Xi ordered the repression of the remaining Boxers, in an attempt to calm the foreign nations.[14]

In popular culture

The Boxer Rebellion is portrayed in the film 55 Days at Peking, by Nicholas Ray (1963).

The Boxers are portrayed in Boxers and Saints, a comic series by Gene Luen Yang. The main character of Boxers, Lee Bao, becomes a leader of the Boxer Rebellion.

See also

- Boxer Rebellion

- Red Turban Rebellion

- Taiping Heavenly Kingdom

- Red Lanterns (Boxer Uprising)

Notes and references

- "Sunday 25 March 1900". TimesMachine. timesmachine.NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- "Australian War Memorial". Archived from the original on 2011-02-18. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- MacKerras, Colin (2008). China in Transformation, 1900–1949. Pearson Longman. ISBN 9781405840583.

- Muramatsu, Yuzi (April 1953). "The "boxers" in 1898–1899, the origin of the "I-Ho-Chuan" (義和拳) uprising, 1900". The Annals of the Hitotsubashi Academy. 3 (2): 236–261. JSTOR 43751277.

- Purcell, Victor (2010-06-03). The Boxer Uprising: A Background Study. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521148122.

- "Boxer Rebellion". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-02-29.

- "Google Ngram Viewer". books.google.com. Retrieved 2019-01-18.

- Esherick, Joseph W. (1987). The origins of the Boxer Uprising. Berkeley, California; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press. p. 141.

- "Le mouvement des boxeurs en chine (1898-1900)". you-feng.com. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- "China, Japan, and the Ryukyu Islands". history-geography. Retrieved 2017-12-03. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - "Chinese monarchs – Zaiyi (26 August 1856 – 24 November 1922) was a Manchu prince and statesman of the late Qing Dynasty". www.nouahsark.com. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- Lucia. "China's Confession: Episode 4". www.chinasoul.org. Archived from the original on 2017-08-31. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- "Significance, Combatants, Definition, & Facts". Boxer Rebellion. Retrieved 2017-12-02. Unknown parameter

|encyclopedia=ignored (help) - "La révolte des Boxeurs, un autre son de cloche". tao-yin.com. Archived from the original on 2011-08-31. Retrieved 2017-12-02.