Xaidulla

Xaidulla[4], also spelled Shahidullah and Shahidula, also Saitula from Mandarin Chinese, is a town in Pishan County in the southwestern part of Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China. It is strategically located on the upper Karakash River, just to the north of the Karakoram Pass on the old caravan route between the Tarim Basin and Ladakh. It lies next to the Chinese National Highway G219 between Kashgar and Tibet, 25 km east of Mazar and 115 km west of Dahongliutan.

Xaidulla 赛图拉 • شەيدۇللا • Шаһидулла Shahidulla | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Etymology: witness or martyr of Allah[1][2] | |

| Nickname(s): Sanshili Yingfang | |

Xaidulla | |

| Coordinates: 36.352°N 78.026°E | |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Region | Xinjiang |

| Prefecture | Hotan |

| County | Pishan/Guma |

| Elevation | 3,646 m (11,962 ft) |

| Xaidulla | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 賽圖拉 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 赛图拉 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 三十里營房 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 三十里营房 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||

| Uyghur | شەيدۇللا | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The modern town is located next to the People's Liberation Army barracks named Sanshili Yingfang[5] or Sanshili Barracks[6] (lit. '30 li barracks'). It is so named because the barracks is 30 "Chinese miles" upstream from the site of the historical border outpost.[2] This name is a more common name used by motorists along the G219 highway.[5]

Etymology

The Uyghur name Shahidulla simply means "witness of Allah"[1] or "martyr of Allah"[2] depending on the interpretation of the heteronym "shahid".

During the 1800s, the place was a sepulcher or shrine for a person known as Shahid Ullah Khajeh[7][8] or Shahidulla Khoja.[9] He was said to be a Khoja from Yarkand who was killed by "his Khitay pursuers" during the 1700s Qing conquest of Xinjiang. His real name was lost. At the time local Kirghiz nomads venerated the shrine and Muslim travelers would pray for blessing on their journey.[9]

Geography and caravan trade

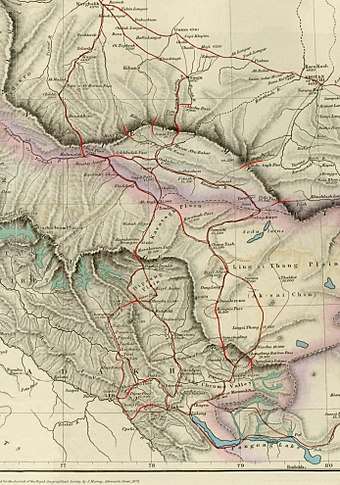

Shahidulla is situated between the Kunlun mountains and the Karakoram range, "close to the southern foot of the former".[10] It is at the western bend of the Karakash River, which originates in the Aksai Chin plains, flows northeast and makes a sharp bend to the west at the foot of the Kunlun range. After making another bend near Shahidulla, it flows northeast again, cutting through the Kunlun mountains towards Khotan. The traditional site of Shahidulla is located northwest of the modern town, about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) downstream.

Caravaners talk about a "southern branch" of the Kunlun range at the foot of which the Karakash flows, and a "northern branch" (also called the "Kilian range") which has various passes (from the west to east, Yangi, Kilik, Kilian, Sanju, Hindu-tagh and Ilchi passes). The Kilian and Sanju passes are the most often mentioned, which lead to Kashgar. To the south of Shahidulla, the trade route passed through Suget Pass and, after crossing the Yarkand River at Ak-tagh, through the Karakoram Pass into Ladakh. An alternative route to Ladakh from Shahidulla (called the "Chang Chenmo route") went along the Karakash river till reaching the Aksai Chin plains and then to Ladakh via the Chang Chenmo valley. The Chang Chenmo route was only feasible for large traders. The Aksai Chin being desolate and barren, they had to carry fodder for the pack animals along with their cargo.

The entire area between the Karakoram range and the Kunlun mountains is mostly uninhabited and has very little vegetation, except for the river valleys of Yarkand and Karakash. In these valleys, during the summer months, cultivation was possible. Kanjutis from Hunza used to cultivate in the Yarkand valley (called "Raskam" plots) and the Kirghiz from Turkestan used to cultivate in the area of Shahidullah. Shahidullah is described as a "seasonal township" in the sources, but it was little more than a campground in the 19th century.[11]

Kulbhushan Warikoo states that, of the two trade routes between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, one in the west through Chitral and the Pamirs, and the other in the east through Shahidulla and Ladakh, the eastern route was more favoured by the traders as it was relatively safe from robberies and political turmoil:

_and_environs_1_-_French_Army_map.jpg)

Such was the safety of this route that in the event of unfavourable weather or death of ponies, traders would march to a safe place leaving behind their goods which were fetched after the climate became favourable or substitute transport became available.[12]

The absence of turmoil was not a given. In fact, the traders applied pressure on the rulers to avoid conflict. The Ladakhi rulers especially heeded such warnings, dependent as they were on trade for their prosperity.[13]

History

There is legendary and documentary evidence that indicates that Indians from Taxila and the Chinese were among the first settlers of Khotan. In the first century BC, Kashmir and Khotan on the two sides of the Karakoram range formed a joint kingdom, which was ruled by either Scythian or Turki (Elighur) chiefs. Towards the end of the first century AD, the kingdom broke up into two parts: Khotan being annexed by the Chinese and Kashmir by Kanishka.[14]

Early records

Some modern scholars believe the Kingdom of Zihe (Chinese: 子合; Wade–Giles: Tzu-ho)[15] in Chinese historical records was situated at Shahidulla.[16][17] This is not universally attested.[18][19]

Edouard Chavannes tentatively identified Zihe as Kargilik,[20] and several later authors have followed this identification. However, Aurel Stein made a strong case that it was, instead, located to the south of Kargilik: "Both the distance indicated and the situation in a confined valley point to one or another of the submontane oases south of Karghalik as the Tzŭ-ho capital here referred to."[21] Of these "submontane oases south of Karghalik," Xaidulla was the most important, being at a key junction of several roads, leading south to Leh in Ladakh, west to Tashkurgan valley and Wakhan, and north to Yarkand and Khotan.

Part of the reason for the confusion in identifying these early kingdoms is the conflation of Zihe with the Kingdom of Xiye (Chinese: 西夜; Wade–Giles: Hsi-yeh) in the historical records themselves.[22][23] Xiye can be identified as town of Kargilik with relatively high confidence.[24] According to the Book of Han, both Xiye and Zihe were ruled by the king of Zihe,[25][22] but the Book of the Later Han indicates the former has an error: “The Hanshu wrongly stated that Xiye [Karghalik] and Zihe formed one kingdom. Each now has its own king.”[23] The other reason is that Stein had made an incorrect estimation of the Han li as being approximately one-fifth of a mile (about 322 metres)[26] instead of the now generally accepted 415.8 metres (1,364 ft).[27] Additionally, both accounts give exactly the same population figures for the conflated kingdoms. The population figures for Zihe in the Book of the Later Han[15] were simply copied from the figures for Xiye in the Book of Han.[22] Book of Han figures probably originally referred to the combined population of both small kingdoms.

16th century

In late 15th century, Mirza Abu Bakr Dughlat from the Dughlat tribe founded an independent kingdom for himself from the fragmentation of Moghulistan. The kingdom encompassed Hotan and Kashgar. However, he was deposed in the 1510s by Sultan Said Khan who founded the Yarkand Khanate. While attempting to flee to Ladakh, Abu Bakr was intercepted and killed. His tomb is located about 30 kilometres (20 miles) north of modern day town of Xaidulla.[28]

Although this region clearly must have remained a welcome stop-over for caravans on the important branch route from the Tarim Basin to Ladakh and India, there are few, if any, further written records of it until the British merchant, Robert Shaw, reached it.[29]

19th century

The Dogra ruler, Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, acting under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire in Lahore, conquered Ladakh in 1834.[30] The primary driver in the conquest was the control the trade that passed through Ladakh. The Dogra general Zorawar Singh Kahluria immediately wanted to invade the Chinese Turkestan. Alarmed by this development, the British put pressure on him via Lahore to desist.[31] However, all the area up to Shahidulla was taken control of by the Dogras, as the Chinese Turkestan then viewed the Kunlun mountains as its southern border.[32] In 1846, the Sikhs gave up Raja Gulab Singh and his domains to the British, who then established him as the Maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir under their suzerainty. Thus began a long tug-of-war between the Dogras and British regarding the control over Shahidulla and in fact the entire tract lying between the Karakoram range and the Kunlun mountains.[33]

The British were inclined to view the Karakoram range as the natural boundary of the Indian subcontinent as it defined a water-parting line, south of which waters flowed into the Indus River and the Arabian Sea and north of which the waters flowed into the Tarim Basin. However, the Turkestanis viewed the northern branch of the Kunlun mountains (sometimes called the "Kilian range") as their frontier. This left the tract between the two as a no man's land. Since there was very little vegetation and almost no habitation in this area, there was no urgent need to control it. However, regular trade caravans passed through the area between Ladakh and Kashgar, which were open to robber raids. Securing trade was of high import to the new regime in Jammu and Kashmir.[30][34]

Robert Barkley Shaw, a British merchant resident in Kangra, India, visited Xaidulla in 1868 on his trip to Yarkand, via Leh, Ladakh and the Nubra Valley, over the Karakoram Pass. He was held in detention there for a time in a small fort made of sun-dried bricks on a shingly plain near the Karakash River which, at that time, was under the control of the Governor of Yarkand on behalf of the ruler of Kashgaria, Yaqub Beg.[35] Shaw says there was no village at all: "it is merely a camping-ground on the regular old route between Ladâk and Yârkand, and the first place where I should strike that route. Four years ago [i.e. in 1864], while the troubles were still going on in Toorkistân, the Maharaja of Cashmeer sent a few soldiers and workmen across the Karakoram ranges (his real boundary) and built a small fort at Shahidoolla. This fort his troops occupied during two summers; but last year, when matters became settled; and the whole country united under the King of Yarkand, these troops were withdrawn."[36]

Robert Shaw's nephew, Francis Younghusband, visited Xaidulla in 1889 and reported: "At Shahidula there was the remains of an old fort, but otherwise there were no permanent habitations. And the valley, though affording that rough pasturage upon which the hardy sheep and goats, camels and ponies of the Kirghiz find sustenance, was to the ordinary eye very barren in appearance, and the surrounding mountains of no special grandeur. It was a desolate, unattractive spot."[37]

He also reported that it was over 12,000 ft (3,658 m) in altitude and that nothing was grown there. All grain had to be imported from the villages of Turkestan, a six days' march over a pass 17,000 ft (5,182 m) high. It was also some 180 miles (290 km) to the nearest village in Ladakh over three passes averaging over 18,000 ft (5,486 m).[38]

20th and 21st centuries

By the early 20th century, the whole region was under Chinese control and considered part of Xinjiang Province,[39] and has remained so ever since. Xaidulla is well to the north of any territories claimed by either India or Pakistan, while the Sanju and Kilian passes are further to the north of Xaidulla. A major Chinese road runs from Yecheng in the Tarim Basin, south through Xaidulla, and across the Aksai Chin region controlled by China, but claimed by India, and into northwestern Tibet.[40]

In May 2010, Xaidulla was made a town.[41]

Administrative divisions

The town includes one village, formerly part of Kangkir Kyrgyz Township:[42][43]

- Serikeke'er (色日克克尔村)

Transportation

Footnotes

- Campbell, Mike. "User-submitted name Shahidullah". Behind the Name. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

Shahidulla, Shahidula, Shahid Allah means "witness of Allah", from Arabic شَهِيد (šahīd) "witness" and الله (Allah).

- "1950年解放军到达昆仑山,国军兄弟说:等了四年,可算来人了" [In 1950 the PLA arrived in Kunlun Mountain, the brothers in KMT Army said: we waited four years (to be relieved), you finally arrived.]. sohu.com. 20 April 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

这里曾经是一个哨所,全名叫塞图拉哨所,营房在海拔3700米的三十里营房,赛图拉这个古老哨所遗址指向牌是由南疆军区前指和和田军分区前指共同所立,距三十里营房十五公里。...赛图拉是维语,汉语意思是殉教者们。

- Northern Ngari in Detail: Activities, Lonely Planet, retrieved 12 September 2018.

- Collins World Atlas Illustrated Edition (3rd ed.). HarperCollins. 2007. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-00-723168-3 – via Internet Archive.

Xaidulla

- "Dring the silk road on China national highway 219 for tour from Xinjiang to Tibet". China Silk Road Tours. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

Day 8: Ali – Bangongcuo Lake – Sanshili Yingfang

- PLA Daily (2006-03-06). "PLA medical station on highest elevation opens". Chinese Embassy in India. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- William Moorcroft; George Trebeck (1841). Horace Hayman Wilson (ed.). Travels in the Himalayan provinces of Hindustan: and the Panjab, in Ladakh and Kashmir, in Peshawar, Kabul, Kunduz, and Bokhara. J. Murray. p. 375.

The former rises in the mountains of Khoten, and runs from east to west for twenty-four kos to Shahid Ullah Khajeh, and then north for twelve kos, where it receives the Toghri su, or straight water, which rises in the Karlik Dawan, or ice mountains.

- Mir Izzet Ullah (1843). "Travels beyond the Himalaya". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 7 (2): 299. JSTOR 25207596.

Near Kirghiz thicket is a pass, by which a road runs in a north-easterly direction to the sepulchre of Shahid Ullah Khajeh, one day's march: one night's journey from hence is a mine of Yeshm.

- Henry Walter Bellew (1875). Kashmir and Kashghar: A Narrative of the Journey of the Embassy to Kashghar in 1873-74. Trübner. p. 185.

Shahidulla Khoja, which gives its name to the locality, is a sacred shrine on the top of a bluff ... upon the grave of some fugitive Khoja from Yarkand, who was killed here by his Khitay pursuers at the time the Chinese conquered the country, a century or so ago. ... his memory is venerated by the Kirghiz nomads of the locality ... Musalman travellers passing this way toil up the slope to repeat a blessing over his tomb, and invoke the nameless martyr's intercession for God's protection on their onward journey.

- Mehra, An "agreed" frontier 1992, p. 62.

- Phanjoubam, The Northeast Question 2015, pp. 12–14.

- Warikoo, Trade relations between Central Asia and Kashmir Himalayas 1996, paragraph 2.

- Rizvi, The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries 1994, pp. 28–29.

- Sastri, K. A. Nilakanta (1967), Age of the Nandas and Mauryas, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 220–221, ISBN 978-81-208-0466-1; Mirsky, Jeannette (1998), Sir Aurel Stein: Archaeological Explorer, University of Chicago Press, p. 83, ISBN 978-0-226-53177-9

- Fan Ye. [Kingdom of Zihe]. Book of the Later Han (in Chinese). 88 – via Wikisource.

- John E. Hill (July 2003). "Section 6 – The Kingdom of Zihe 子合 (modern Shahidulla)". Notes to The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu (2nd ed.). Washington University. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Ulrich Theobald (Oct 16, 2011). "Pishan 皮山 and the states in the Pamir Range". ChinaKnowledge.de. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

During the Later Han period the state fell apart in Xiye proper and the state of Zihe 子合 (modern name Shahidullah).

- Rong, Xinjiang (Feb 2007). "阚氏高昌王国与柔然、西域的关系" [Relations of the Gaochang Kingdom under the Kan Family with the Rouran Qaghanate and the Western Regions during the Second Half of the 5th Century] (PDF). Historical Research (in Chinese). ISSN 0459-1909. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

子合国在西域南道, 今和田与塔什库尔干之间的叶城县治哈尔噶里克 (Karghalik)

- 中国古代史 (in Chinese). 中国人民大学书报资料社. 1982. p. 54.

子合的位置应即今日帕米尔高原的小帕米尔东部,塔克敦巴什帕米尔南部地区,东延直至喇斯库穆及密尔岱西南山区一带。

- Les pays d’Occident d’après le Heou Han chou.” Édouard Chavannes. T’oung pao 8 (1907), p. 175, n. 1.

- Stein, Serindia (1921), Vol. I, pp. 86-87

- [Kingdom of Xiye]. Book of Han (in Chinese). 096上 – via Wikisource.

西夜國,王號子合王 ... 而子合土地出玉石。

- Fan Ye. [Kingdom of Xiye]. Book of the Later Han (in Chinese). 88 – via Wikisource.

《汉書》中误云西夜、子合是一國,今各自有王。

- John E. Hill (July 2003). "Section 5 – The Kingdom of Xiye 西夜 (modern Karghalik or Yecheng)". Notes to The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu (2nd ed.). Washington University. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

the directions given in the Hanshu and the population figures given in the Hou Hanshu make it almost certain that it represents modern Karghalik, as Aurel Stein first pointed out

- Hulsewé & Loewe (1979), p. 100

- Stein, Serindia (1921), Vol. I, pp. 86-87

- “Han Measures.” A.F.P. Hulsewé. T’oung Pao, Second Series, Vol. 49, Livr. 3 (1961), p. 467.

- Bellew, Henry Walter (1875). The history of Káshgharia. p. 62.

[Sa'id] took possession of the city at end of Rajab 920H ... Ababakar fled before them from Khutan to Caranghotagh. ... fled towards Tibt. ... He was intercepted, seized, and killed by a party of his many pursuers in the Caracash valley, where a mean tomb on the river bank, two stages from Shahidulla Khoja, now marks the site of his grave.

- Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand, and Kashgar. Robert Shaw. London, John Murray. Reprint, Hong Kong, Oxford University Press, 1984.

- Rizvi, The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (1994), pp. 37–38.

- Datta, Chaman Lal (1984), General Zorawar Singh, His Life and Achievements in Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet, Deep & Deep Publications, p. 63

- Mehra, An "agreed" frontier (1992), p. 57: "Shahidulla was occupied by the Dogras almost from the time they conquered Ladakh."

- Mehra, An "agreed" frontier (1992): "In his detailed memorandum, Younghusband recalled it was always accepted that the frontier extended up to the Muztagh mountains and the Karakoram pass, the only unsettled question being as to whether it should include Shahidulla."

- Fisher, Rose & Huttenback, Himalayan Battleground (1963), pp. 64–65.

- Shaw (1871), pp. 100-

- Shaw (1871), p. 107

- Younghusband (1924), p. 108

- Younghusband (1896), pp. 223-224

- Stanton (1908), Map. No. 19 - Sinkiang

- National Geographic Atlas of China (2008), p. 28.

- 皮山县历史沿革 [Pishan County Historical Development] (in Chinese). XZQH.org. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

2010年5月,自治区政府批准设立赛图拉镇。

- 2009年皮山县行政区划 [2009 Pishan County Administrative Divisions] (in Chinese). XZQH.org. 6 January 2011. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

653223212 康克尔柯尔克孜族乡 {...} 653223212203 220 色日克克尔村

- 2018年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:赛图拉镇 [2018 Statistical Area Numbers and Rural-Urban Area Numbers: Xaidulla Town] (in Chinese). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2018. Retrieved 16 January 2020.

统计用区划代码 城乡分类代码 名称 653223102200 121 色日克克尔村委会

References

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Rose, Leo E.; Huttenback, Robert A. (1963), Himalayan Battleground: Sino-Indian Rivalry in Ladakh, Praeger – via Questia

- Hill, John E. (2015), Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE Volumes I and II., Charleston, SC.: CreateSpace, ISBN 978-1500696702, and. For a downloadable early draft of this book see the Silk Road Seattle website hosted by the University of Washington at: https://depts.washington.edu/silkroad/texts/texts.html

- Hulsewé, A.F.P.; Loewe, M. A. N. (1979), China in Central Asia: The Early Stage: 125 B.C.-A.D. 23, Leiden: E.J. Brill, ISBN 90-04-05884-2

- Mehra, Parshotam (1992), An "agreed" frontier: Ladakh and India's northernmost borders, 1846-1947, Oxford University Press

- National Geographic Atlas of China (2008). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-1-4262-0136-3.

- Phanjoubam, Pradip (2015), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and frontiers, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-34003-4

- Rizvi, Janet (2016). "The trans-Karakoram trade in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries". The Indian Economic & Social History Review. 31 (1): 27–64. doi:10.1177/001946469403100102. ISSN 0019-4646.

- Shaw, Robert (1984) [first published by John Murray in 1871], Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-583830-0

- Stanton, Edward (1908), Atlas of the Chinese Empire. (Prepared for the China Inland Mission), London: Morgan & Scott Ltd.

- Stein, M. Aurel (1921), Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols., London, Oxford, Clarendon Press. Reprint, Motilal Banarsidass, 1980. London; Delhi. File downloadable from:

- Warikoo, K. (1996), "Trade relations between Central Asia and Kashmir Himalayas during the Dogra period (1846-1947)", Cahiers d'Asia Centrale

- Younghusband, Francis (1977) [1924], Wonders of the Himalayas, Chandigarh: Abhishek Publications

- Younghusband, Francis (2005) [first published by John Murray in 1896], The Heart of a Continent, Elbiron Classics, ISBN 1-4212-6551-6, (pbk); (hardcover)