Sengoku period

The Sengoku period (戦国時代, Sengoku Jidai, "Age of Warring States") is a period in Japanese history of near-constant civil war, social upheaval, and political intrigue from 1467 to 1615.

| History of Japan |

|---|

Battle of Kawanakajima (1561). |

The Sengoku period was initiated by the Ōnin War in 1467 which collapsed the feudal system of Japan under the Ashikaga Shogunate. Various samurai warlords and clans fought for control over Japan in the power vacuum, while the Ikkō-ikki emerged to fight against samurai rule. The arrival of Europeans in 1543 introduced the arquebus into Japanese warfare, and Japan ended its status as a tributary state of China in 1549. Oda Nobunaga dissolved the Ashikaga Shogunate in 1573 and launched a war of political unification by force, including the Ishiyama Hongan-ji War, until his death in the Honnō-ji Incident in 1582. Nobunaga's successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi completed his campaign to unify Japan and consolidated his rule with numerous influential reforms. Hideyoshi launched the Japanese invasions of Korea in 1592, but their eventual failure damaged his prestige before his death in 1598. Tokugawa Ieyasu displaced Hideyoshi's young son and successor Toyotomi Hideyori at the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and re-established the feudal system under the Tokugawa Shogunate. The Sengoku period ended when Toyotomi loyalists were defeated at the Siege of Osaka in 1615.[1][2]

The Sengoku period was named by Japanese historians after the otherwise unrelated Warring States period of China.[3] Modern Japan recognizes Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu as the three "Great Unifiers" for their restoration of central government in the country.

Summary

During this period, although the Emperor of Japan was officially the ruler of his nation and every lord swore loyalty to him, he was largely a marginalized, ceremonial, and religious figure who delegated power to the shōgun, a noble who was roughly equivalent to a general. In the years preceding this era, the shogunate gradually lost influence and control over the daimyōs (local lords). Although the Ashikaga shogunate had retained the structure of the Kamakura shogunate and instituted a warrior government based on the same social economic rights and obligations established by the Hōjō with the Jōei Code in 1232, it failed to win the loyalty of many daimyō, especially those whose domains were far from the capital, Kyoto. Many of these lords began to fight uncontrollably with each other for control over land and influence over the shogunate. As trade with Ming China grew, the economy developed, and the use of money became widespread as markets and commercial cities appeared. Combined with developments in agriculture and small-scale trading, this led to the desire for greater local autonomy throughout all levels of the social hierarchy. As early as the beginning of the 15th century, the suffering caused by earthquakes and famines often served to trigger armed uprisings by farmers weary of debt and taxes.

The Ōnin War (1467–1477), a conflict rooted in economic distress and brought on by a dispute over shogunal succession, is generally regarded as the onset of the Sengoku period. The "eastern" army of the Hosokawa family and its allies clashed with the "western" army of the Yamana. Fighting in and around Kyoto lasted for nearly 11 years, leaving the city almost completely destroyed. The conflict in Kyoto then spread to outlying provinces.[1][4]

The period culminated with a series of three warlords, Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who gradually unified Japan. After Tokugawa Ieyasu's final victory at the siege of Osaka in 1615, Japan settled down into over two-hundred years of peace under the Tokugawa shogunate.

Timeline

The Ōnin War in 1467 is usually considered the starting point of the Sengoku period. There are several events which could be considered the end of it: Nobunaga's entry to Kyoto (1568)[5] or abolition of the Muromachi shogunate (1573),[6] the Siege of Odawara (1590), the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), the establishment of the Tokugawa Shogunate (1603), or the Siege of Osaka (1615).

| Time | Event |

|---|---|

| 1467 | Beginning of Ōnin War |

| 1477 | End of Ōnin War |

| 1488 | The Kaga Rebellion |

| 1493 | Hosokawa Masamoto succeeds in the Coup of Meio |

| Hōjō Sōun seizes Izu Province | |

| 1507 | Beginning of Ryo Hosokawa War (the succession dispute in the Hosokawa family) |

| 1520 | Hosokawa Takakuni defeats Hosokawa Sumimoto |

| 1523 | China suspends all trade relations with Japan due to the conflict |

| 1531 | Hosokawa Harumoto defeats Hosokawa Takakuni |

| 1535 | Battle of Idano The forces of the Matsudaira defeat the rebel Masatoyo |

| 1543 | The Portuguese land on Tanegashima, becoming the first Europeans to arrive in Japan, and introduce the arquebus into Japanese warfare |

| 1549 | Miyoshi Nagayoshi betrays Hosokawa Harumoto |

| Japan officially ends its recognition of China's regional hegemony and cancel any further tribute missions | |

| 1551 | Tainei-ji incident: Sue Harukata betrays Ōuchi Yoshitaka, taking control of western Honshu |

| 1554 | The tripartite pact among Takeda, Hōjō and Imagawa is signed |

| 1555 | Battle of Itsukushima: Mōri Motonari defeats Sue Harukata and goes on to supplant the Ōuchi as the foremost daimyo of western Honshu |

| 1560 | Battle of Okehazama: The outnumbered Oda Nobunaga defeats and kills Imagawa Yoshimoto in a surprise attack |

| 1568 | Oda Nobunaga marches toward Kyoto forcing Matsunaga Danjo Hisahide to relinquish control of the city |

| 1570 | Beginning of Ishiyama Hongan-ji War |

| 1571 | Nagasaki is established as trade port for Portuguese merchants, with authorization of daimyo Õmura Sumitada |

| 1573 | The end of Ashikaga shogunate |

| 1575 | Battle of Nagashino: Oda Nobunaga decisively defeats the Takeda cavalry with innovative arquebus tactics |

| 1577 | Siege of Shigisan: Oda Nobunaga defeats Matsunaga Danjo Hisahide |

| 1580 | End of Ishiyama Hongan-ji War |

| 1582 | Akechi Mitsuhide assassinates Oda Nobunaga (Honnō-ji Incident); Hashiba Hideyoshi defeats Akechi at the Battle of Yamazaki |

| 1585 | Hashiba Hideyoshi is granted title of Kampaku, establishing his predominant authority; he is granted the surname Toyotomi a year after. |

| 1590 | Siege of Odawara: Toyotomi Hideyoshi defeats the Hōjō clan, unifying Japan under his rule |

| 1592 | First invasion of Korea |

| 1597 | Second invasion of Korea |

| 1598 | Toyotomi Hideyoshi dies |

| 1600 | Battle of Sekigahara: The Eastern Army under Tokugawa Ieyasu defeats the Western Army of Toyotomi loyalists |

| 1603 | The establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate |

| 1614 | Catholicism is officially banned and all missionaries are ordered to leave the country |

| 1615 | Siege of Osaka: The last of the Toyotomi opposition to the Tokugawa shogunate is stamped out |

Gekokujō

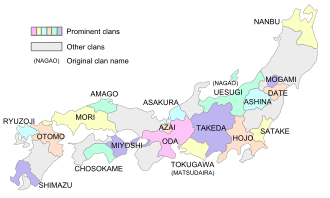

The upheaval resulted in the further weakening of central authority, and throughout Japan, regional lords, called daimyōs, rose to fill the vacuum. In the course of this power shift, well-established clans such as the Takeda and the Imagawa, who had ruled under the authority of both the Kamakura and Muromachi bakufu, were able to expand their spheres of influence. There were many, however, whose positions eroded and were eventually usurped by more capable underlings. This phenomenon of social meritocracy, in which capable subordinates rejected the status quo and forcefully overthrew an emancipated aristocracy, became known as gekokujō (下克上), which means "low conquers high".[1]

One of the earliest instances of this was Hōjō Sōun, who rose from relatively humble origins and eventually seized power in Izu Province in 1493. Building on the accomplishments of Sōun, the Hōjō clan remained a major power in the Kantō region until its subjugation by Toyotomi Hideyoshi late in the Sengoku period. Other notable examples include the supplanting of the Hosokawa clan by the Miyoshi, the Toki by the Saitō, and the Shiba clan by the Oda clan, which was in turn replaced by its underling, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a son of a peasant with no family name.

Well-organized religious groups also gained political power at this time by uniting farmers in resistance and rebellion against the rule of the daimyōs. The monks of the Buddhist True Pure Land sect formed numerous Ikkō-ikki, the most successful of which, in Kaga Province, remained independent for nearly 100 years.

Unification

After nearly a century of political instability and warfare, Japan was on the verge of unification by Oda Nobunaga, who had emerged from obscurity in the province of Owari (present-day Aichi Prefecture) to dominate central Japan. In 1582, Oda was assassinated by one of his generals, Akechi Mitsuhide, and allowed Toyotomi Hideyoshi the opportunity to establish himself as Oda's successor after rising through the ranks from ashigaru (footsoldier) to become one of Oda's most trusted generals. Toyotomi eventually consolidated his control over the remaining daimyōs but ruled as Kampaku (Imperial Regent) as his common birth excluded him from the title of Sei-i Taishōgun. During his short reign as Kampaku, Toyotomi attempted two invasions of Korea. The first attempt, spanning from 1592 to 1596, was initially successful but suffered setbacks from the Joseon Navy and ended in a stalemate. The second attempt began in 1597 but was less successful as the Koreans, especially their navy, led by Admiral Yi Sun-Sin, were prepared from their first encounter. In 1598, Toyotomi called for retreat from Korea prior to his death.

Without leaving a capable successor, the country was once again thrust into political turmoil, and Tokugawa Ieyasu took advantage of the opportunity.[2]

On his deathbed, Toyotomi appointed a group of the most powerful lords in Japan—Tokugawa, Maeda Toshiie, Ukita Hideie, Uesugi Kagekatsu, and Mōri Terumoto—to govern as the Council of Five Regents until his infant son, Hideyori, came of age. An uneasy peace lasted until the death of Maeda in 1599. Thereafter a number of high-ranking figures, notably Ishida Mitsunari, accused Tokugawa of disloyalty to the Toyotomi regime.

This precipitated a crisis that led to the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, during which Tokugawa and his allies, who controlled the east of the country, defeated the anti-Tokugawa forces, which had control of the west. Generally regarded as the last major conflict of the Sengoku period, Tokugawa's victory at Sekigahara effectively marked the end of the Toyotomi regime, the last remnants of which were finally destroyed in the Siege of Osaka in 1615.

Notable people

Three unifiers of Japan

The contrasting personalities of the three leaders who contributed the most to Japan's final unification—Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa—are encapsulated in a series of three well known senryū:

- Nakanu nara, koroshite shimae, hototogisu (If the cuckoo does not sing, kill it.)

- Nakanu nara, nakasete miyō, hototogisu (If the cuckoo does not sing, coax it.)

- Nakanu nara, naku made matō, hototogisu (If the cuckoo does not sing, wait for it.)

Oda, known for his ruthlessness, is the subject of the first; Toyotomi, known for his resourcefulness, is the subject of the second; and Tokugawa, known for his perseverance, is the subject of the third verse.

See also

- History of Japan

- List of daimyōs from the Sengoku period

- List of Japanese battles

- Horses in East Asian warfare

- Warring States period – a similar period in Chinese history

- Crisis of the Third Century – a similar period in Roman history

- Zemene Mesafint – a similar period in Ethiopian history from the early 18th century until the reign of Tewodros II in the mid–19th century

- Kabukimono

Notes

- "Sengoku period". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "誕". Kokushi Daijiten (in Japanese). Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 683276033. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Sansom, George B. 2005. A History of Japan: 1334–1615. Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Publishing.

- "Ōnin War". Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Shogakukan. 2012. OCLC 56431036. Archived from the original on 2007-08-25. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- Mypaedia 1996.

- Hōfu-shi Rekishi Yōgo-shū.

References

- "Sengoku Jidai". Hōfu-shi Rekishi Yōgo-shū (in Japanese). Hōfu Web Rekishi-kan.

- Hane, Mikiso (1992). Modern Japan: A Historical Survey. Westview Press.

- Chaplin, Danny (2018). Sengoku Jidai. Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu: Three Unifiers of Japan. CreateSpace Independent Publishing. ISBN 978-1983450204.

- Hall, John Whitney (May 1961). "Foundations of The Modern Japanese Daimyo". The Journal of Asian Studies. Association for Asian Studies. 20 (3): 317–329. doi:10.2307/2050818. JSTOR 2050818.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674003349/ISBN 9780674003347. OCLC 44090600.

- Lorimer, Michael James (2008). Sengokujidai: Autonomy, Division and Unity in Later Medieval Japan. London: Olympia Publishers. ISBN 978-1-905513-45-1.

- "Sengoku Jidai". Mypaedia (in Japanese). Hitachi. 1996.

External links

- Sengoku Period - Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Samurai Archives Japanese History page

- (in Japanese) Sengoku Expo: Japanese Design, Culture in the Age of Civil Wars held in Gifu Prefecture, 2000–2001

- (in Japanese) List of the Sengoku Daimyos

| Preceded by Nanboku-chō period (1334–1392) (of Muromachi Period) |

History of Japan Sengoku period 1467–1573 (of Muromachi Period) |

Succeeded by Azuchi–Momoyama period 1573–1603 |