Scale (anatomy)

In most biological nomenclature, a scale (Greek λεπίς lepis, Latin squama) is a small rigid plate that grows out of an animal's skin to provide protection. In lepidopteran (butterfly and moth) species, scales are plates on the surface of the insect wing, and provide coloration. Scales are quite common and have evolved multiple times through convergent evolution, with varying structure and function.

.jpg)

Scales are generally classified as part of an organism's integumentary system. There are various types of scales according to shape and to class of animal.

Fish scales

Fish scales are dermally derived, specifically in the mesoderm. This fact distinguishes them from reptile scales paleontologically. Genetically, the same genes involved in tooth and hair development in mammals are also involved in scale development.[1]

Cosmoid scales

True cosmoid scales can only be found on the Sarcopterygians. The inner layer of the scale is made of lamellar bone. On top of this lies a layer of spongy or vascular bone and then a layer of dentine-like material called cosmine. The upper surface is keratin. The coelacanth has modified cosmoid scales that lack cosmine and are thinner than true cosmoid scales.

Ganoid scales

Ganoid scales can be found on gars (family Lepisosteidae), bichirs, and reedfishes (family Polypteridae). Ganoid scales are similar to cosmoid scales, but a layer of ganoin lies over the cosmine layer and under the enamel. Ganoin scales are diamond shaped, shiny, and hard. Within the ganoin are guanine compounds, iridescent derivatives of guanine found in a DNA molecule.[2] The iridescent property of these chemicals provide the ganoin its shine.

Placoid scales

Placoid scales are found on cartilaginous fish including sharks. These scales, also called denticles, are similar in structure to teeth, and have one median spine and two lateral spines.

Leptoid scales

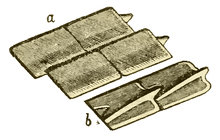

Leptoid scales are found on higher-order bony fish. As they grow they add concentric layers. They are arranged so as to overlap in a head-to-tail direction, like roof tiles, allowing a smoother flow of water over the body and therefore reducing drag.[3] They come in two forms:

Reptilian scales

Reptile scale types include: cycloid, granular (which appear bumpy), and keeled (which have a center ridge). Scales usually vary in size, the stouter, larger scales cover parts that are often exposed to physical stress (usually the feet, tail and head), while scales are small around the joints for flexibility. Most snakes have extra broad scales on the belly, each scale covering the belly from side to side.

The scales of all reptiles have an epidermal component (what one sees on the surface), but many reptiles, such as crocodilians and turtles, have osteoderms underlying the epidermal scale. Such scales are more properly termed scutes. Snakes, tuataras and many lizards lack osteoderms. All reptilian scales have a dermal papilla underlying the epidermal part, and it is there that the osteoderms, if present, would be formed.

Avian scales

Birds' scales are found mainly on the toes and metatarsus, but may be found further up on the ankle in some birds. The scales and scutes of birds were thought to be homologous to those of reptiles,[4] but are now agreed to have evolved independently, being degenerate feathers.[5][6]

Mammalian scales

An example of a scaled mammal is the pangolin. Its scales are made of keratin and are used for protection, similar to an armadillo's armor. They have been convergently evolved, being unrelated to mammals' distant reptile-like ancestors, except that they use a similar gene.

On the other hand, the musky rat-kangaroo has scales on its feet and tail.[7] The precise nature of its purported scales has not been studied in detail, but they appear to be structurally different from pangolin scales.

Anomalures also have scales on their tail undersides.[8]

Foot pad epidermal tissues in most mammal species have been compared to the scales of other vertebrates. They are likely derived from cornification processes or stunted fur much like avian reticulae are derived from stunted feathers.[9]

Arthropod scales

Butterflies and moths - the order Lepidoptera (Greek "scale-winged") - have membranous wings covered in delicate, powdery scales, which are modified setae. Each scale consists of a series of tiny stacked platelets of organic material, and butterflies tend to have the scales broad and flattened, while moths tend to have the scales narrower and more hair like. Scales are usually pigmented, but some types of scales are metallic, or iridescent, without pigments; because the thickness of the platelets is on the same order as the wavelength of visible light the plates lead to structural coloration and iridescence through the physical phenomenon described as thin-film optics. The most common color produced in this fashion is blue, such as in the Morpho butterflies. Other colors can be seen on the sunset moth.

See also

- Scale (insect anatomy)

- Armour (anatomy)

- Psoriasis: a long-lasting autoimmune disease characterized by patches of thin pieces of hard skin like scale.

References

- Sharpe PT (September 2001). "Fish scale development: Hair today, teeth and scales yesterday?". Current Biology. 11 (18): R751–2. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00438-9. PMID 11566120.

- Levy-Lior A, Pokroy B, Levavi-Sivan B, Leiserowitz L, Weiner S, Addadi L (2008). "Biogenic guanine crystals from the skin of fish may be designed to enhance light reflectance". Crystal Growth and Design. 8 (2). pp. 507–511. doi:10.1021/cg0704753.

- Ballard B, Cheek R (2 July 2016). Exotic Animal Medicine for the Veterinary Technician. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-92421-1.

- Lucas AM (1972). Avian Anatomy - integument. East Lansing, Michigan, USA: USDA Avian Anatomy Project, Michigan State University. pp. 67, 344, 394–601.

- Zheng X, Zhou Z, Wang X, Zhang F, Zhang X, Wang Y, Wei G, Wang S, Xu X (March 2013). "Hind wings in Basal birds and the evolution of leg feathers". Science. 339 (6125): 1309–12. Bibcode:2013Sci...339.1309Z. doi:10.1126/science.1228753. PMID 23493711.

- Sawyer RH, Knapp LW (August 2003). "Avian skin development and the evolutionary origin of feathers". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 298 (1): 57–72. doi:10.1002/jez.b.26. PMID 12949769.

- "Musky Rat Kangaroo". Rainforest-Australia.com. Archived from the original on 2013-10-30. Retrieved 2014-03-08.

- Fleming T, Macdonald D, eds. (1984). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 632. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- Spearman RI (1973). The integument: a textbook of skin biology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20048-6.

Further reading

- Kardong KV (1998). Vertebrates: Comparative Anatomy, Function, Evolution (second ed.). USA: McGraw-Hill. p. 747. ISBN 978-0-697-28654-3.