Sawney Bean

Alexander "Sawney" Bean was said to be the head of a 45-member clan in Scotland in the 16th century that murdered and cannibalized over 1000 people in the span of 25 years. According to legend, Bean and his clan members would eventually be caught by a search party sent by King James VI and be executed for their heinous crimes.

Sawney Bean | |

|---|---|

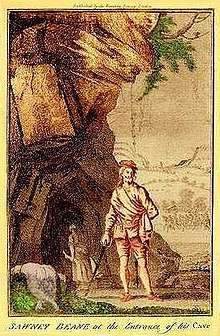

Sawney Bean at the Entrance of His Cave. Note the woman in the background carrying two disembodied legs and the dead body nearby. | |

| Born | Alexander Bean |

| Other names | Sawney |

| Spouse(s) | Agnes "Black" Douglas |

| Children | 29 |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

| Details | |

| Victims | 5,593 |

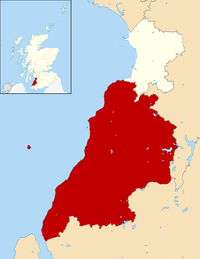

| Country | Scotland |

The story appeared in The Newgate Calendar, a crime catalogue of Newgate Prison in London. The legend lacks sufficient evidence to be deemed as factual by historians, and there is debate as to why the legend would have been fictionalized. Nevertheless, the myth of "Sawney" Bean has passed into local folklore and has become part of the Edinburgh tourism circuit.

Legend

According to The Newgate Calendar, a tabloid publication from the 18th and 19th centuries, Alexander Bean was born in East Lothian during the 16th century.[1] His father was a ditch-digger and hedge-trimmer and Bean tried to take up the family trade, but quickly realized that he was not fit for this work.

He left home with a vicious woman named "Black" Agnes Douglas, who apparently shared his inclinations and was accused of being a witch. After some robbing and the cannibalization of one of their victims, the couple ended up at a coastal cave in Bennane Head between Girvan and Ballantrae. The cave was 200 yards deep, and the entrance was blocked by water during high tide, so the couple were able to live there undiscovered for some 25 years.

Sawney and Agnes produced eight sons, six daughters, 18 grandsons and 14 granddaughters. Various grandchildren were products of incest between their children.

Lacking the inclination for regular labour, the Bean clan thrived by laying careful ambushes at night to rob and murder individuals or small groups. The clan brought the bodies back to their cave where the corpses were dismembered and eaten. They pickled the leftovers in barrels. The clan discarded body parts, which would sometimes wash up on nearby beaches. This strategy was used to help conceal their crimes and lead villagers to believe that it was animals who were attacking travelers.

The body parts and disappearances did not go unnoticed by the local villagers, but the Bean clan stayed in their cave by day and took their victims at night. The Bean clan was so secretive that the villagers were unaware of the murderers living nearby.

As local people began to take notice of the disappearances more significantly, several organized searches were launched to find the culprits. One search took note of the cave but the men refused to believe anything human could live in it. Frustrated and in a frenetic quest for justice, the townspeople lynched several innocents, but the disappearances continued. Suspicion often fell on local innkeepers since they were the last known to have seen many of the missing people alive.

One fateful night, the Bean clan ambushed a married couple riding from a fayre on one horse, but the man was skilled in combat, thus he deftly held off the clan with sword and pistol. The Bean clan fatally mauled the wife when she fell to the ground in the conflict. Before they could take the resilient husband, a large group of fayre-goers appeared on the trail and the Beans fled. The fayre-goers took the survivor to the local magistrate, whom they informed of this experience.

With the Beans' existence finally revealed, it was not long before the King (perhaps James VI of Scotland in tales linked to the 16th century, though it is less clear who this could be in other tales from the 15th century) heard of the atrocities and decided to lead a search with a team of 400 men and several bloodhounds. They soon found the Bean clan's previously overlooked cave in Bennane Head thanks to the bloodhounds. Upon entering the cave by torchlight, the searchers found the Bean clan surrounded by human remains with some body parts hanging from the wall, barrels filled with limbs, and piles of stolen heirlooms and jewellery.

There were two versions on what happened next:

- The most common of the two is that the Bean clan was captured alive where they gave up without a fight. They were taken in chains to the Tolbooth Jail in Edinburgh, then transferred to Leith or Glasgow where they were promptly executed without trial as people saw them as subhuman and unfit for one. Sawney and his fellow men had their genitalia cut off and thrown into the fires, their hands and feet severed, and were allowed to bleed to death, with Sawney shouting his dying words: "It isn't over, it will never be over." After watching the men die, Agnes, her fellow women, and the children were tied to stakes and burned alive. These execution practices recall, in essence if not in detail, the punishments of hanging, drawing, and quartering decreed for men convicted of treason. In contrast, women convicted of the same were burned.

- There was another claim that the search party placed gunpowder at the entrance of their cave, where the Sawney Bean Clan faced the fate of suffocation.

The town of Girvan, located near the macabre scene of murder and debauchery, has another legend about the Bean clan. There are claims that one of Bean's daughters eventually left the clan and settled in Girvan where she planted a Dule tree that became known as "The Hairy Tree." After her family's capture and exposure, the daughter's identity was revealed by angry locals who hanged her from the bough of the Hairy Tree.

Sources and veracity

According to The Scotsman, there is a debate over the validity of the Sawney Bean tale. Some people believe that Sawney Bean was a real person, while others think he was just a mythical figure. Dorothy L. Sayers offered a gruesome account of the Sawney Bean tale in her anthology Great Short Stories of Detection, Mystery and Horror (Gollancz, 1928. The book was a best-seller in Britain, reprinted seven times in the next five years.)[2] A 2005 article by Sean Thomas[3] notes that historical documents, such as newspapers and diaries during the era in which Sawney Bean was supposedly active, make no mention of ongoing disappearances of hundreds of people. Additionally, Thomas notes inconsistencies in the stories but speculates that kernels of truth might have inspired the legend:

... from broadsheet to broadsheet, the precise dating of Sawney Bean's reign of anthropophagic terror varies wildly: sometimes the atrocities occurred during the reign of James VI [ca. early 1600s], whilst other versions claim the Beans lived centuries before. Viewed in this light, it is arguable that the Bean story may have a basis of truth but the precise dating of events has become obscured over the years. Perhaps the dating of the murders was brought forward by the editors and writer of the broadsheets, so as to make the story appear more relevant to the readership ... To add to the intrigue, we do know that cannibalism was not unknown in mediaeval Scotland and that Galloway was in mediaeval times a very lawless place; perhaps nothing on the scale of the Bean legend took place, but every story grows and is embroidered over time.

The Sawney Bean legend closely resembles the story of Christie-Cleek, which is attested much earlier in the early 15th century. Christine-Cleek is a mythical Scottish cannibal who lived during a famine in the mid-fourteenth century.

The legend of Sawney Bean first appeared in the British chapbooks (rumour magazines of the day). Today, many argue that the story was a political propaganda tool to denigrate the Scots after the Jacobite rebellions. Thomas disagrees, noting:

If the Sawney Bean story is to be read as deliberately anti-Scottish, how do we explain the equal emphasis on English criminals in the same publications? Wouldn't such an approach rather blunt the point? (See also "Sawney" for this theory).

Another cannibal story from Scotland, even more redolent of the Sawney Bean tale than the Christie-Cleek story, can be found in the 1696 work of Nathaniel Crouch, a compiler and popular history writer who published under the pseudonym "Richard Burton." In this tale, the following happened in 1459, the year before James II of Scotland's death:[4]

..about which time a certain thief who lived privately in a den, with his wife and children, were all burned alive, they having made it their practice for many years to kill young people and eat them; one girl only of a year old was saved, and brought up at Dundee, who at twelve years of age being found guilty of the same horrid crime, was condemned to the same punishment, and when the people followed her in great multitudes to execution, wondering at her unnatural villainy, she turned toward them, and with a cruel countenance said, "What do you thus rail at me, as if I had done such an heinous act, contrary to the nature of man? I tell you that if you did but know how pleasant the taste of man's flesh was, none of you all would forbear to eat it;" and thus with an impenitent and stubborn mind she suffered deserved death.

Hector Boece notes that the infant daughter of a Scot brigand, who was executed with his family for cannibalism, though raised by foster parents, developed the cannibal appetite at 12, and was put to death for it. This was summarised by George M. Gould and Walter Pyle in Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine.[5]

Popular culture

- Wes Craven used Sawney Bean as the inspiration for his film The Hills Have Eyes.[6]

- Sawney Bean is used as direct inspiration for the name of two titans in the manga and anime series Attack on Titan written by Hajime Isayama.

- The legend's influence can also be seen in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre.[7]

- In the Image comics series Hack/Slash, the main character Vlad (a.k.a. "The Meatman Killer") is eventually revealed to be a descendant of Sawney Bean.

References

- "Sawney Beane". Archived from the original on 2010-06-10.

- http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?1066965

- Thomas, Sean (April 2005). "In Search of Sawney Bean". Fortean Times. Archived from the original on May 19, 2008. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- Stace, Machell (1813). The History of the Kingdom of Scotland. p. 135.

- Gould, George M.; Pyle, Walter L. (1896). Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: W.B. Saunders. p. 409. OCLC 07028696. Retrieved 14 November 2016.

- Maddrey, Joseph (2004). Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-7864-1860-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/scotland/history/sawney_bean.shtml The Grisly Deeds of Alexander Bean The BBC

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sawney Beane. |