Savoy Theatre

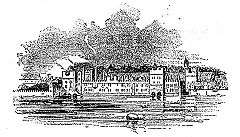

The Savoy Theatre is a West End theatre in the Strand in the City of Westminster, London, England. The theatre opened on 10 October 1881 and was built by Richard D'Oyly Carte on the site of the old Savoy Palace as a showcase for the popular series of comic operas of Gilbert and Sullivan, which became known as the Savoy operas as a result.

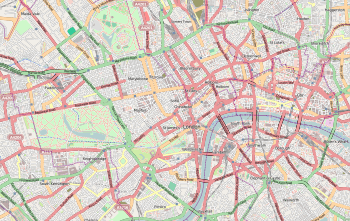

Original façade of the Savoy Theatre, 1881 | |

Savoy Theatre Location within Central London | |

| Address | Savoy Court, Strand London, WC2 |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.5101°N 0.1209°W |

| Public transit | |

| Owner | Ambassador Theatre Group |

| Operator | Ambassador Theatre Group |

| Type | West End theatre |

| Capacity | c. 1,150 on 3 levels |

| Construction | |

| Opened | 10 October 1881 |

| Rebuilt |

|

| Architect | C. J. Phipps |

| Website | |

| www | |

The theatre was the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity. For many years, the Savoy Theatre was the home of the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company, which continued to be run by the Carte family for over a century. Richard's son Rupert D'Oyly Carte rebuilt and modernised the theatre in 1929, and it was rebuilt again in 1993 following a fire. It is a Grade II* listed building.

In addition to The Mikado and other famous Gilbert and Sullivan premières, the theatre has hosted such premières as the first public performance in England of Oscar Wilde's Salome (1931) and Noël Coward's Blithe Spirit (1941). In recent years it has presented opera, Shakespeare and other non-musical plays, and musicals.

History of the site

The House of Savoy was the ruling family of Savoy descended from Humbert I, Count of Sabaudia (or "Maurienne"), who became count in 1032. The name Sabaudia evolved into "Savoy" (or "Savoie"). Count Peter (or Piers or Piero) of Savoy (d. 1268) was the maternal uncle of Eleanor of Provence, queen-consort of Henry III of England, and came with her to London.[1]

King Henry made Peter Earl of Richmond and, in 1246, gave him the land between The Strand and the Thames where Peter built the Savoy Palace in 1263. On Peter's death, the Savoy was given to Edmund, 1st Earl of Lancaster, by his mother, Queen Eleanor. Edmund's great-granddaughter, Blanche, inherited the site. Her husband, John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, built a magnificent palace that was burned down by Wat Tyler's followers in the Peasants' Revolt of 1381. King Richard II was still a child, and his uncle John of Gaunt was the power behind the throne and so a main target of the rebels.[1]

In about 1505 Henry VII planned a great hospital for "pouer, nedie people", leaving money and instructions for it in his will. The hospital was built in the palace ruins and was licensed in 1512. Drawings show that it was a magnificent building, with a dormitory, dining hall and three chapels. Henry VII's hospital lasted for two centuries but suffered from poor management. The sixteenth-century historian John Stow noted that the hospital was being misused by "loiterers, vagabonds and strumpets". In 1702 the hospital was dissolved, and the hospital buildings were used for other purposes. Part of the old palace was used for a military prison in the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth century, the old hospital buildings were demolished and new buildings erected.[1]

In 1864 a fire burned everything except the stone walls and the Savoy Chapel, and the property sat empty until Richard D'Oyly Carte bought it in 1880 to build the Savoy Theatre specifically for the production of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas that he was producing.[2] The new theatre was built speedily, and accounts noted that it "was situated on a site which, though rich in historical associations, was also rich in the olfactory sense, Mr Rimmel's scent factory being close by as was Burgess's Noted Fish-Sauce Shop."[3]

Richard D'Oyly Carte's theatre

Carte bought the freehold of the site, then known as "Beaufort Buildings", early in 1880 for £11,000, but had begun planning his theatre several years before. In 1877 he engaged Walter Emden, an architect whose work includes the Garrick and the Duke of York's theatres.[4] Before completing the site purchase, city officials had assured Carte that they would open a new street on the south side of the plot, provided he paid half the cost. He paid his half in March 1880, but the officials caused lengthy delays. Carte told The Times, "I am struggling in the meshes of red tape".[5] He finally received the necessary agreement in June. At the same time he ran into another obstacle: Emden suddenly revised his estimate of building costs upward from £12,000 to £18,000. Carte dismissed Emden, who successfully sued for £1,790 for services to date and £3,000 for wrongful dismissal.[4]

Design of the theatre was given to C. J. Phipps. The builders were Patman and Fotheringham. Plans were drawn up and executed with speed and efficiency. Nonetheless, the advertised opening date had to be put back several times while the innovative electrical work was completed.[4] The Savoy finally opened on 10 October 1881.[6] Carte had at one time intended to call it the Beaufort Theatre,[7] but he announced in a letter to The Daily Telegraph in 1881, "On the Savoy Manor there was formerly a theatre. I have used the ancient name as an appropriate title for the present one."[4] The exterior of the building was made from red brick and Portland stone.[8] The interior decoration, by Collinson and Locke, was "in the manner of the Italian Renaissance", with white, pale yellow and gold predominating, including a gold satin curtain (instead of the usual printed act-drop), red boxes and dark blue seats.[9] There were none of the cherubs, deities and mythical creatures familiar from the décor of rival theatres. Carte wanted nothing that would appear too garish or gaudy to his target, middle-class audience.[8]

On the opening night Phipps took curtain calls along with Gilbert, Sullivan and Carte.[4] The Times commented, "A perfect view of the stage can be had from every seat in the house."[9] Exits on all four sides of the theatre were provided, and fireproof materials were used to ensure maximum safety.[9] There were three tiers with four levels: stalls and pit, balcony, circle, and amphitheatre and gallery at the top. The total seating capacity was 1,292.[10] The proscenium arch was 30 feet (9.1 m) high by 30 feet (9.1 m) wide, and the stage was 27 feet (8.2 m) deep from the proscenium to the back wall.[11] The theatre originally had its main entrance on the Embankment. The parcel on which it was built is steep, stretching from the Strand down to the Embankment along Beaufort Street. After Carte built the Savoy Hotel in 1889, the theatre entrance was moved to its present location at the hotel's courtyard off the Strand.[12]

.jpg)

The Savoy was a state-of-the-art theatre and the first public building in the world to be lit entirely by electricity.[9][13] In 1881, Sir Joseph Swan, inventor of the incandescent light bulb, supplied about 1,200 Swan incandescent lamps, and the lights were powered by a 120-horsepower (89 kW) generator on open land near the theatre.[9][14] Carte explained why he had introduced electric light: "The greatest drawbacks to the enjoyment of the theatrical performances are, undoubtedly, the foul air and heat which pervade all theatres. As everyone knows, each gas-burner consumes as much oxygen as many people, and causes great heat beside. The incandescent lamps consume no oxygen, and cause no perceptible heat."[15] The first generator proved too small to power the whole building, and though the entire front-of-house was electrically lit, the stage was lit by gas until 28 December 1881. At that performance, Carte stepped onstage and broke a glowing lightbulb before the audience to demonstrate the safety of the new technology. The Times described the electric lighting as superior, visually, to gaslight.[16] Gaslights were installed as a backup, but they rarely had to be used.[4] The Times concluded that the theatre "is admirably adapted for its purpose, its acoustic qualities are excellent, and all reasonable demands of comfort and taste are complied with."[17] Carte and his manager, George Edwardes (later famous as manager of the Gaiety Theatre), introduced several innovations including numbered seating, free programme booklets, good quality whisky in the bars, the "queue" system for the pit and gallery (an American idea) and a policy of no tipping for cloakroom or other services.[3][18] Daily expenses at the theatre were about half the possible takings from ticket sales.[13][19]

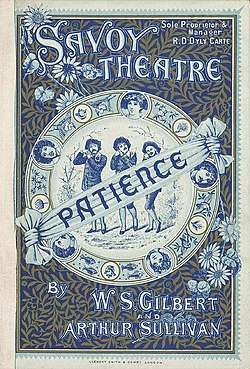

The work that opened the new theatre was Gilbert and Sullivan's comic opera Patience, which had been running since April 1881 at the smaller Opera Comique.[3] The last eight of Gilbert and Sullivan's comic operas were premièred at the Savoy: Iolanthe (1882), Princess Ida (1884), The Mikado (1885), Ruddigore (1887), The Yeomen of the Guard (1888) The Gondoliers (1889), Utopia, Limited (1893), and The Grand Duke (1896), and the term Savoy opera has come to be associated with all their joint works. After the end of the Gilbert and Sullivan partnership, Carte, and later his widow, Helen (and her manager from 1901 to 1903, William Greet), staged other comic operas at the theatre by Arthur Sullivan and others, notably Ivan Caryll, Sydney Grundy, Basil Hood and Edward German.[20] The Savoy Operas of the 1890s, however, were far less successful than those of the Gilbert and Sullivan heyday. After Carte's production of The Chieftain ended in March 1895, the Theatre briefly hosted the Carl Rosa Opera Company and then closed until late 1895, when Carte resumed productions at the theatre. Sullivan died in 1900, and Richard D'Oyly Carte died in 1901.[21]

The Savoy Theatre closed in 1903, and was reopened under the management of John Leigh and Edward Laurillard from February 1904 (beginning with a musical, The Love Birds) to December 1906.[7] The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company returned to the Savoy for repertory seasons between 1906 and 1909, in which year C. H. Workman took over the management of the theatre. He produced, among other works, Gilbert's final opera, with music by German, Fallen Fairies in 1909–10, which ran for only 51 performances.[22] He also produced Two Merry Monarchs and Orpheus and Eurydice in 1910, the latter of which starred Marie Brema and Viola Tree in the title roles.[23] The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company did not play in the theatre from 1909 until 1929,[24] instead touring throughout Britain and playing London seasons in other theatres; other works held the stage of the Savoy. George Augustus Richardson managed the theatre from November 1911 to February 1915.[7] The Mikado's record as the Savoy's longest-running production was broken by the comedy Paddy the Next Best Thing by Gertrude Page, which played for 867 performances from April 1920.[25]

Rupert D'Oyly Carte's theatre

In 1915 Richard D'Oyly Carte's son, Rupert D'Oyly Carte, took over management of the theatre.[7] After serving in the navy in World War I, Carte decided to bring the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company back to London in first-rate style. He began to mount seasons of updated and refreshed Gilbert and Sullivan productions at first at the Prince's Theatre in 1919.[3] J. B. Fagan's adaptation of Treasure Island first played in December 1922 at the Savoy Theatre with Arthur Bourchier as Long John Silver.[26] It was so popular that it was revived every Christmas until the outbreak of World War II.[27]

On 3 June 1929 Carte closed the Savoy Theatre, and the interior was completely rebuilt to designs by Frank A. Tugwell with elaborate décor by Basil Ionides. The ceiling was painted to resemble an April sky; the walls, translucent gold on silver; the rows of stalls were all richly upholstered in different colours, and the curtain repeated the tones of the seating. Ionides said that he took the colour scheme from a bed of zinnias in Hyde Park.[3] The entire floor space had been replanned: the old cloakrooms and bar at the back of the theatre were relocated to the side, and instead of 18 boxes there was now only one. The new auditorium had two tiers leaving three levels: stalls, dress, and upper circle. The capacity of the old house, originally 1,292, had been reduced to 986 by 1912,[28] and the new theatre restored the capacity almost completely, with 1,200 seats.[29] The new stage was 29.3 feet wide, by 29.5 feet deep.[7]

The theatre reopened on 21 October 1929 with a new production of The Gondoliers designed by Charles Ricketts and conducted by Malcolm Sargent.[30] In the only box sat Lady Gilbert, the librettist's widow.[3] There were Gilbert and Sullivan seasons at the Savoy Theatre in 1929–30, 1932–33, 1951, 1954, 1961–62, 1975, 2000, 2001, 2002 and 2003. Other famous works presented at the Savoy included the première of Noël Coward's Blithe Spirit (1941, which ran 1,997 consecutive performances, setting a new record for non-musical theatre runs), Robert Morley in The Man Who Came to Dinner, and several comedies by William Douglas-Home starring, among others, Ralph Richardson, Peggy Ashcroft, and John Mills. The long-delayed first public performance in England of Oscar Wilde's Salome played at the theatre in 1931.[31]

After Rupert D'Oyly Carte died in 1948 his daughter, Bridget D'Oyly Carte, succeeded to the D'Oyly Carte Opera Company and became a director and later president of the Savoy Hotel group, which controlled the theatre. Management of the theatre was assumed in 1948 by Sir Hugh Wontner, chairman of the Savoy hotel group.[7] The theatre was designated a Grade II* listed building in 1973.[32] The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company closed in 1982, and Dame Bridget died childless in 1985, bringing the family line to an end. Wontner continued as chairman of the theatre until his death in 1992.[33]

1990 fire and restored theatre

While the theatre was being renovated in February 1990, a fire gutted the building, except for the stage and backstage areas. A proposal to build a new theatre in late 20th-century style was overruled by the Savoy's insurers and by English Heritage, the government body with oversight of listed buildings. It was decided to restore the building as faithfully as possible to the 1929 designs.[34] Tugwell's and Ionides's working designs had been preserved, allowing accurate restoration of the theatre under the direction of the architect Sir William Whitfield, Sir Hugh Wontner and the theatre's manager, Kevin Chapple.[35] It reopened on 19 July 1993, with a royal gala that included a specially commissioned ballet, Savoy Suite, by Wayne Sleep to a score based on Sullivan's music.[36] The present theatre has a capacity of 1,158. During the renovation, an extra storey was added above the theatre that includes a health club for the hotel and a swimming pool above the stage. The reopened theatre was the venue for the World Chess Championship in 1993, won by Garry Kasparov.[37]

In 1993 Noël Coward's Relative Values, played at the theatre, having premièred there in 1951, an original run of 477 performances.[38] Tom Stoppard's Travesties, with Antony Sher was next, and in 1994 the musical She Loves Me played, with Ruthie Henshall and John Gordon Sinclair. These were followed by Terry Johnson's Dead Funny; Alan Ayckbourn's Communicating Doors (which transferred to the theatre in 1996), with Angela Thorne; J. B. Priestley's When We Are Married, with Dawn French, Alison Steadman, and Leo McKern; and Ben Travers' Plunder, with Griff Rhys Jones and Kevin McNally. In 1997 a group led by Sir Stephen Waley-Cohen was given management of the theatre by The Savoy Group. Productions that followed included Simon Callow in The Importance of Being Oscar; Pet Shop Boys in concert; Ian Richardson in Pinero's The Magistrate; Edward Fox in A Letter of Resignation; the Royal Shakespeare Company's production of Richard III, with Robert Lindsay; and Coward's Hay Fever, with Geraldine McEwan in 1999.

In 2000 the briefly reconstituted D'Oyly Carte Opera Company produced H.M.S. Pinafore at the theatre. Donald Sutherland then starred in Enigmatic Variations, followed by a second D'Oyly Carte season, playing The Pirates of Penzance.[39] In 2002, a season of Return to the Forbidden Planet was followed by the D'Oyly Carte productions of Iolanthe, The Yeomen of the Guard and The Mikado, and then a revival of Yasmina Reza's Life x 3. In 2003, the company revived Pinafore, followed by Bea Arthur at The Savoy, John Steinbeck's Of Mice and Men, Peter Pan and Pirates. These were followed by The Marriage of Figaro and The Barber of Seville performed by The Savoy Opera Company in 2004. Next were seasons of Lorna Luft starring in Songs My Mother Taught Me and the new salsa musical Murderous Instincts. Coward's Blithe Spirit was revived in 2004–05.[39]

The Savoy Hotel group, including the theatre, was sold in 2004 to Quinlan Private which, in turn, sold the theatre in 2005 to the Ambassador Theatre Group (ATG) and the Tulbart Group (selling the Savoy Hotel to Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal).[40][41] Productions since then have been mostly revivals and transfers of modern musicals; major productions have included The Rat Pack: Live from Las Vegas and a new musical theatre version of Porgy and Bess, directed by Trevor Nunn (both in 2006), Fiddler on the Roof (2007–08),[42] Carousel (2008–09),[43] Legally Blonde (2010–12),[44] Let It Be (2013–14),[45] Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (2014–15),[46] Gypsy (2015),[47] Funny Girl (2016),[48] Dreamgirls (2016–19)[49] and 9 to 5: The Musical (2019–May 2020).[50]

In December 2013, ATG acquired sole ownership of the Savoy.[51]

Notes

- "The Savoy", British History Online, University of London, retrieved 15 April 2015

- Ainger, p. 193

- Bettany, unnumbered page (there are no page numbers in the book)

- "100 Electrifying Years", The Savoyard, Volume XX no. 2, D'Oyly Carte Opera Trust, September 1981, pp. 4–6

- Carte, Richard D'Oyly. "Building Difficulties", The Times, 22 May 1880, p. 6

- Rollins and Witts, p. 8

- Howard, p. 214

- Oost, p. 59

- "The Savoy Theatre", The Times, 3 October 1881

- 18 private boxes (72 seats); 150 stalls, 250 pit, 160 balcony, 160 circle, and 500 (maximum) amphitheatre and gallery. "The Savoy Theatre", The Times, 3 October 1881

- Who's Who in the Theatre, 1912, p. 297. Chapple, p. 11, and Howard, p. 214, give the dimensions as 60 feet wide by 52 feet deep, but those measurements included the wing space and the scene dock at the rear.

- Goodman, p. 27

- Burgess, Michael. "Richard D'Oyly Carte", The Savoyard, January 1975, pp. 7–11

- Henderson, Tony. "Tale of tragedy behind the triumphs of Joseph Swan", The Journal, 28 September 2011, accessed 11 December 2016

- Baily, p. 215

- "Savoy Theatre", The Times, 28 December 1881, p. 4

- "The Savoy Theatre", The Times, 11 October 1881

- Wilson and Lloyd, p. 29

- Dark and Grey, p. 85

- Rollins and Witts, pp. 16–19

- Wilson and Lloyd, p. 52

- Rollins and Witts, p. 22

- Wearing, vol. 1, p. 24

- Rollins and Witts, pp. 22–154.

- Gaye, p. 1536

- "London Life – a commentary" The West Australian 31 January 1923, p. 10

- Chapman, p. 32

- Who's Who in the Theatre, 1912, p. 297. The seating plan in that edition shows only 8 boxes instead of the original 18, and reduced numbers of seats in the Dress (156) and Upper Circle (127) (as they were by then named).

- "Reopening of the Savoy", The Times, 21 October 1929.

- Rupert D'Oyly Carte's 1929–30 Season at the G&S Archive

- Ellis, Samantha. "Salomé, Savoy Theatre, October 1931", 26 March 2003, accessed 22 February 2013

- Historic England. "Grade II* (1236724)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- The Times, obituary of Hugh Wontner, 27 November 1992

- Young, John. "Royal gala marks rebirth of D'Oyly Carte's theatre". The Times, 20 July 1993, p. 6

- Kevin Chapple obituary, The Stage, 8 January 2008, accessed 30 November 2011

- Church, Michael. "An object all sublime", The Observer, 30 May 1993, p. 55 (subscription required)

- Keene, Raymond and Ian Murray. "Kasparov clinches world title after Short accepts draw", The Times, 20 October 1993, p. 10

- Gaye, p. 1537

- Information from the Ambassador Theatre Group's website

- Walsh, Dominic. "Savoy Group changes name after deal", The Times, 25 January 2005

- Bawden, Tom. "Curtain rises on new Savoy Theatre owner", The Times, 13 October 2005; Wolf, Tom. "Savoy Theater (sic) sold to Ambassador", 13 October 2005, accessed 7 July 2013

- Fiddler on the Roof, This is Theatre, accessed 15 April 2015

- "Carousel Posts Closing Notices at Savoy, 20 Jun". WhatsOnStage, 9 June 2009. Retrieved on 28 December 2010

- "Legally Blonde Ends West End Run Tonight", BroadwayWorld.com, 7 April 2012

- O'Boyle, Claire. "Let It Be top of your list", The Sunday Mirror, 24 February 2013

- Maxwell, Dominic. "Comic vitality and saucy staging make up for lack of oomph", The Times, 3 April 2014

- "Gypsy's five star return to London's West End", BBC News, 16 April 2015

- "Victoria Wood remembered at Funny Girl opening", BBC News, 21 April 2016

- "Lion King helped Dreamgirls transfer to West End", BBC News, 15 December 2016

- "Dolly Parton’s 9 to 5 The Musical is coming to the West End", Official London Theatre, 18 September 2018

- Shenton, Mark. "U.K.'s Ambassador Theatre Group Acquires Complete Ownership of West End's Savoy and Playhouse Theatres" Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Playbill.com, 3 December 2013

References

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Allen, Reginald (1975). The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan (centennial ed.). London: Chappell. ISBN 978-0-903443-10-4.

- Baily, Leslie (1956). The Gilbert and Sullivan Book (fourth ed.). London: Cassell. OCLC 21934871.

- Bettany, Clemence (1975). D'Oyly Carte Centenary 1875–1975. London: D'Oyly Carte Opera Trust. OCLC 3511414.

- Chapman, Don (2009). Oxford Playhouse: High and Low Drama in a University City. Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 978-1-902806-86-0.

- Chapple, Kevin; Jane Thorne (1993). Reflected Light: The Story of the Savoy Theatre. London: Dewynters. OCLC 80573775.

- Dark, Sidney; Rowland Grey (1923). W. S. Gilbert: His Life and Letters. London: Methuen. OCLC 3389751.

- Earl, John; Michael Sell (2000). Guide to British Theatres 1750–1950. London: Theatres Trust. ISBN 978-0-7136-5688-6.

- Gaye, Freda (1967). Who's Who in the Theatre (fourteenth ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 5997224.

- Goodman, Andrew (1988). Gilbert and Sullivan's London. Tunbridge Wells and New York: Spellmount (UK) and Hippocrene (US). ISBN 978-0-87052-441-7.

- Howard, Diana (1970). London Theatres and Music Halls 1850–1950. Old Woking: Library Association and Gresham Press. ISBN 978-0-85365-471-1.

- Oost, Regina (2009). Gilbert and Sullivan: Class and the Savoy Tradition, 1875–1896. Farnham, UK and Burlington, US: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6412-3.

- Parker, John (1912). Who's Who in the Theatre (first ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman and Sons. OCLC 320573141.

- Rollins, Cyril; R John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419.

- Wearing, J P. The London Stage, 1910–1919: A Calendar of Players and Plays. New Jersey: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-1596-4.

- Wilson, Robin; Frederic Lloyd (1984). Gilbert & Sullivan – The D'Oyly Carte Years. London York: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-78505-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Savoy Theatre, London. |