Satellaview

The Satellaview[lower-alpha 1] is a satellite modem peripheral produced by Nintendo for the Super Famicom in 1995. Containing 1 megabit of ROM space and an additional 512 kB of RAM, Satellaview allowed players to download games, magazines and other forms of content through satellite broadcasts provided by Japanese company St.GIGA. To use Satellaview, players had to purchase a special broadcast satellite (BS) tuner directly from St.GIGA or rent one for a six-month fee, and to pay monthly maintenance fees to both St.GIGA and Nintendo. It was attached to the bottom of the Super Famicom via the system's expansion port. It featured heavy support from third-party developers, including Squaresoft, Taito, Konami, Capcom and Seta.

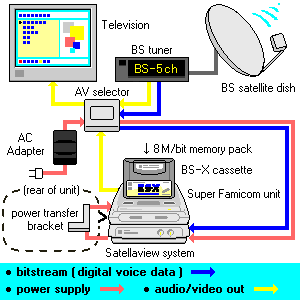

A Satellaview device connected to a Super Famicom. | |

| Developer | Nintendo R&D2 and St. GIGA |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Nintendo |

| Type | Video game console peripheral |

| Generation | Fourth generation |

| Release date |

|

| Discontinued |

|

| Media | ROM cartridge, Flash memory |

| Storage | Game Pak, 8M Memory Pak |

Satellaview was the result of a collaboration between Nintendo and St.GIGA, the latter being known in Japan for its "Tide of Sound" nature sound music. By 1994, St.GIGA was struggling financially due to the Japanese Recession affecting the demand for its music; Nintendo initiated a "rescue" plan by purchasing a stake in the company. Satellaview was produced by Nintendo Research & Development 2, the same team that designed the Super Famicom itself, and was made to cater towards a more adult-oriented market. By 1998, Nintendo's relationship with St.GIGA was beginning to collapse due to the company refusing to go forward with a debt-management plan and failing to secure a government broadcasting license. Nintendo withdrew support for Satellaview in March 1999, with St.GIGA continuing to supply content until June 30, 2000, when it was ultimately discontinued.

The rise of technologically-superior consoles such as the Sega Saturn and PlayStation and its high cost made consumers reluctant to purchase Satellaview, especially due to it only being sold via mail order, or through specific electronic store chains. Despite this, St.GIGA reported seeing over 100,000 subscribers by March 1997. Retrospectively, Satellaview has been praised by critics for its technological accomplishments and the overall quality of its games, particularly those from the Legend of Zelda series. In recent years, it has gained a strong cult following due to much of its content being deemed lost, with video game preservation groups being formed to dump and preserve its games and other services online.

History

Founded in early 1990, St.GIGA was a satellite radio subsidiary of the Japanese satellite television company WOWOW, Inc, based out of Akasaka, Tokyo.[1] Credited as the world's first digital satellite radio station,[2] it was maintained by Hiroshi Yokoi and best known for its "Tide of Sound" broadcasts, which were high-quality digital recordings of nature sounds accompanied by a spoken word narrator known as the "Voice".[3] The company was initially a success, and is recognized for its innovative concept and nonstandard methodology. It later began releasing albums featuring its own music as well as foreign music such as Hearts of Space and various compositions by Deep Forest, as well as various pieces of merchandise such as program guides and "sound calendars".[4] By 1994, St.GIGA was struggling financially due to the Japanese Recession affecting the demand for ambient music, and made consumers reluctant to invest in satellite antennas and tuners.[2][5] Nintendo purchased a 19.5% stake in St.GIGA in May, as a way to "rescue" the company and help to successfully restructure it.[1][2]

Satellaview began development shortly after the acquisition, reportedly in production alongside the Virtual Boy and Nintendo 64.[6] While Nintendo was producing the console, St.GIGA revamped its broadcasting schedule to include a new programming block, the "Super Famicom Hour", which provided gameplay tips and news for upcoming Nintendo games on Super Famicom.[2] St.GIGA would provide the necessary satellite and broadcasting services, as well as host many of its older music and Tide of Sound broadcasts, while Nintendo and other third-party developers would create games and other content for the peripheral.[2] Nintendo stressed to video game publications that much of Satellaview's content, namely broadcasts by St.GIGA themselves, were aimed primarily for adults, with video games constituting only a small portion of airtime.[6]

Nintendo officially announced Satellaview on December 21, 1994, set to be released at a retail price of ¥14,000, or US$150.[7] Several third-party developers, such as Capcom, Taito, Konami, Seta and Squaresoft, announced plans to produce games for the peripheral following its unveiling.[7] The peripheral itself was designed by Nintendo Research & Development 2, the same team that designed the Super Famicom.[8] Despite the company being in a slump due to falling Super Famicom game sales and the Virtual Boy's failure, Nintendo remained confident that Satellaview would be successful and would help calm any supposed "fears" by consumers that the company was on the way out; company president Hiroshi Yamauchi expected to sell roughly 2 million Satellaviews each year.[2][6] Pre-orders were made available beginning February 25, 1995.[2] Broadcasting services for Satellaview launched on April 1, though the peripheral itself was not released until April 24.[9] It was only sold via mail order, instead of being released into stores.[6] Satellaview was never released in North America, which some publications cited as being due to expensive costs of satellite broadcasting, and due to a supposed lack of appeal to American consumers.[10] When the service first launched, St.GIGA had a number of issues regarding broadcasting video games and video game-related services through the Satellaview service, such as legal issues with other companies and technical restraints of the time.[11] In June 1996, Nintendo announced that they would partner with Microsoft to release a service similar to Satellaview for Windows operating systems, which would combine St.GIGA's broadcasting services with dial-up Internet; this was never launched.[12] By March 1997, St.GIGA reported that Satellaview had 116,378 active players.[13]

By the summer of 1998, Nintendo's relationship with St.GIGA began to deteriorate. St.GIGA refused to go forward with a debt-management plan created by Nintendo to reduce the firm's capital, despite being ¥8.8 billion in debt, and had also failed to apply for a government digital satellite broadcasting license under a set deadline.[14] This led to Nintendo halting all production of new games and content for the peripheral beginning March 1999, and had also scrapped plans to continue providing content and services via a new BS-4 satellite.[1][14] Despite this, St.GIGA continued to supply content for Satellaview, broadcasting reruns of older content and making the service strictly for video games.[5] Ultimately, Satellaview was discontinued on June 30, 2000, due to a severe lack of support from other companies and a dwindling player base, dropping by nearly 60% from its peak in 1997 to about 46,000 active subscribers.[1] A year after it was discontinued, St.GIGA declared bankruptcy and merged itself with Japanese media company WireBee, Inc.[15]

Technical specifications

A Satellaview device attaches to the bottom of a Super Famicom, in a manner similar to the 64DD or the Sega CD. It does not require the use of the original Super Famicom power adapter, as it transfers power to the Super Famicom through a power transfer bracket placed at the back of the console.[6] The peripheral itself contains 1 MB of ROM space and 512 kB of RAM to increase memory performance of the Super Famicom.[6] A Satellaview device is packaged with a custom four-way AC adapter and AV selector, which are used to connect the console to a BS tuner that is required to operate it.[6] 8 MB memory packs were used to save game and broadcast information, inserted into the top of a special application cartridge.[16] These memory packs can be rewritten with new content, and can also be used in conjunction with other certain Super Famicom games, such as RPG Maker 2.[16] In order to use Satellaview, a user had to purchase a custom BS tuner from St.GIGA themselves, and pay monthly fees to both St.GIGA and Nintendo;[16] players could also rent a BS tuner for a six-month period at ¥5,400.[17] A satellite dish was also required.[6]

The application cartridge of Satellaview, titled BS-X: Sore wa Namae o Nusumareta Machi no Monogatari (commonly translated as BS-X: The Town Whose Name Was Stolen), serves as both an interactive menu system and its own game.[16] It was inserted into the Super Famicom's cartridge port, and is required to use the peripheral.[10] The game features an EarthBound-esque hub world, featuring different buildings that represented each of Satellaview's different services and entertainment venues.[16] Players can create a custom avatar, purchase items found in stores scattered across the map, and play short minigames, as well as read announcements made by St.GIGA and Nintendo and participate in contests.[10][16] The BS-X cartridge also helps increase the Super Famicom's hardware performance with extra on-board RAM.[16]

Games and services

A total of 114 games were released for Satellaview; some of these consist of remakes or alterations of older Family Computer and Super Famicom games, while others were created specifically for the service.[10] Nintendo produced several Satellaview games based on its popular franchises, including Kirby, F-Zero, Fire Emblem, The Legend of Zelda and Super Mario Bros.[5] Nintendo also contributed several original games, such as Sutte Hakkun.[18] EarthBound creator Shigesato Itoi designed a fishing game called Itoi Shigesato no Bass Tsuri No. 1.[10] The previously-unreleased Special Tee Shot, later reworked into Kirby's Dream Course, was also released for the service.[19] Noteworthy third-party titles include Squaresoft's Radical Dreamers and Treasure Conflix, Pack-In-Video's Harvest Moon, Chunsoft's Shiren the Wanderer, Jaleco's Super Earth Defense Force, and ASCII's Derby Stallion '96.[5] Some games were labeled as "Soundlink games", titles that featured live voice-acting from various radio personalities and commentators.[20] Unlike other games for Satellaview, SoundLink games could only be played during their specific broadcast time.[20] Nintendo often held tournaments for certain games, such as Wario's Woods, that allowed players to compete against others in a chance to win prizes.[5]

Alongside games, Satellaview subscribers could also access many other different services. Magazines were made available for free, ranging from video game publications like Famitsu and Nintendo Power to general Japanese publications focusing on news, music or interviews with celebrities.[21][22] There were also Soundlink magazines that had commentary often provided by popular Japanese personalities, such as Bakushō Mondai and All Night Nippon.[5] Subscribers were also given access to broadcasts provided by St.GIGA themselves, such as its "Tide of Sound" nature ambiance and other forms of music.[21] A special newsletter by both St.GIGA and Nintendo was also provided, which featured updates on the service such as contest and info on upcoming events.[21]

Reception and legacy

Despite having amassed a larger playerbase, and being widely-successful for St.GIGA, Nintendo viewed Satellaview as a commercial failure.[5] The rise of technologically-superior consoles such as Sega Saturn and PlayStation, as well as Nintendo's own Nintendo 64, made consumers reluctant to purchase Satellaview, especially due to it being sold only through mail order delivery, or specific electronic stores.[5]

Retrospective feedback on Satellaview has been positive. Retro Gamer magazine applauded the peripheral for its technological achievements, providing an early form of online gaming decades before the advent of services such as Xbox Live.[10] Retro Gamer also commended its selection of games for their overall quality, citing the BS Legend of Zelda games as the definitive set of titles for the peripheral.[10] Nintendo World Report liked the service for being "unique", one that will likely never be replicated on modern video game consoles, as well as its selection of games and services available for it.[16] Shack News listed it among Nintendo's most innovative products for its technological accomplishments and for being one of the first attempts at bringing video games online.[23] Kill Screen labeled Satellaview as "perhaps one of the most crucial early experiments in combining games with storytelling", specifically being impressed towards the console's Soundlink games and usage of voice acting.[24] At the same time, they also expressed disappointment towards this, due to the entirety of the Soundlink content being lost due to it being performed within real time.[24] Video Game Chronicle called it "an impressive and ingenious idea for the time, and an innovation that we see to a lesser degree now in terms of interactive television and episodic game installments from modern studios."[20]

In 1999, Nintendo released a spiritual successor to Satellaview for Nintendo 64, called the 64DD.[10] Originally announced in 1995, a year prior to the launch of the console itself,[25] the 64DD had many similar features to Satellaview, such as being able to view a special newsletter from Nintendo, and download data from the online network service Randnet.[26] The 64DD also allowed other users to chat with each other, and be able to play games online through private servers.[27] Nintendo attempted to have St.GIGA transition from Satellaview to the 64DD, however, when they refused, Nintendo instead partnered with Japanese media company Recruit to form Randnet.[5] The 64DD was a commercial failure with only around 15,000 units sold, making it Nintendo's worst-selling console of all time.[28]

Satellaview has gained a large cult following in the late 2000s; due to most of its content being lost after the service was closed, many video game preservationists and Nintendo fans have begun searching for memory packs that might still contain game data on them in order to dump and preserve them online.[29] Several dedicated fans have also created custom private servers that work with the official BS-X application cartridge, as well as translating certain games such as those from the Legend of Zelda series.[30][31] Publications have also raised concerns over Satellaview in retrospective years, due to much of its content — specifically audio from Soundlink games and Satellaview digital newsletters — being permanently lost due to these being broadcast in real time.[10][20][24][32]

Notes

References

- "BSラジオ放送のセント・ギガ、民事再生法申請". Nikkei News Media. Nikkei, Inc. Archived from the original on 26 July 2001. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- McClure, Steve. "Japan's St. Giga to Broadcast Nintendo Games". Billboard-Hollywood Media Group. Billboard. pp. 78–84. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Toop, David & Réveillon, Arnaud. Ocean of Sound: ambient music, mondes imaginaires et voix de l'éther. Editions Kargo. Pp. 164-5. 2000. ISBN 2-84162-048-4

- "セント・ギガ ギャラリー". St.GIGA. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Kemps, Heidi (9 September 2015). "Nintendo's Forgotten Console". Vice. Vice Media. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Nintendo aims high with "Satellaview"" (5). Imagine Publishing. Next Generation. May 1995. pp. 18–19. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Special K (1 March 1995). "Japan News Network" (Volume 3, Issue 3). International Data Group. GamePro. pp. 114–115. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Mago, Zdenko (April 5, 2018). "The "Father" Of the Nintendo Entertainment SystemIn Slovakia for The First Time - Interview With Masayuki Uemura" (PDF). Acta Ludogica. 1: 52–54.

Due to the growing demand for development, he was in charge of the management of the Research & Development 2 Division in which they worked on the development of several hardware devices such as games for colour televisions, Nintendo Family Computer (Famicom), Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), Super Nintendo Entertainment System or BS-X Satellaview.

- "Virtual Boy: Nintendo names the day" (8). Imagine Publishing. Next Generation. August 1995. p. 18. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Obscura Machinia #5 - Satellaview" (87). United Kingdom: Future Publishing. Retro Gamer. March 2011. pp. 82–83. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "ファミ通エクスプレス 任天堂が衛星放送事業に参入 ゲームライフの未来が変わる" (Vol. 9, No. 8). ASCII Corporation. Famitsu. 26 February 1993. p. 9.

- Hiroe (26 June 1996). "衛星データ放送と パソコン・インターネットを統合". PC Watch. Impress Group. Archived from the original on 15 May 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "セント・ギガの歴史". St.GIGA. Archived from the original on 11 March 2010. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- "Nintendo Drops Satellite Plan, Video-Game Company Halts Plan To Deliver Games Directly To Homes". CNN. WarnerMedia. 21 August 1998. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "St.GIGA,民事再生手続きが終了,ディジタルBS放送専業で再出発". Nikkei News Media. Nikkei, Inc. 10 June 2002. Archived from the original on 19 June 2002. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Bivens, Danny (27 October 2011). "Satellaview - Nintendo's Expansion Ports". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "セント・ギガ ギャラリー ● デコーダー". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 20 February 2009.

- Lopes, Gonçalo (12 November 2017). "Super Famicom Exclusive Sutte Hakkun Gets Translated Into English". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Lopes, Gonçalo (17 June 2019). "A Forgotten (And Kirby-Free) HAL SNES Title Has Been Preserved For The Ages". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Vincent, Brittany (15 May 2019). "What Becomes Of Unplayable Games?". Video Game Chronicle. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- 懐かしスーパーファミコン パーフェクトガイド. QBQ, Inc. 21 September 2016. pp. 114–115. ISBN 9784866400082. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Knezevic, Kevin (13 May 2017). "New Super Nintendo Game Coming Out In Japan". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Shack Staff (29 July 2016). "Shack Ten: Nintendo's Most Innovative Products". Shack News. Archived from the original on 3 November 2016. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Campana, Andrew (26 September 2016). "The Neglected History Of Videogames For The Blind". Kill Screen. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Nintendo's Lincoln Speaks Out on the Ultra 64!". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 78. Sendai Publishing. January 1996. pp. 74–75.

- "Inside Randnet". IGN. 27 August 1999. Archived from the original on January 5, 2002. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- Schneider, Peer (February 9, 2001). "Everything About the 64DD". IGN. Retrieved June 12, 2014.

- Miyamoto, Shigeru; Itoi, Shigesato (December 1997). "A friendly discussion between the "Big 2" (translated text)". The 64 Dream: 91. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- Wawro, Alex (8 November 2016). "Preservationists find and acquire rare Kirby Satellaview games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 29 April 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Lopes, Gonçalo (7 July 2016). "Japan-Exclusive Satellaview Zelda Game Gets Translated And Dubbed Into English". Nintendo Life. Archived from the original on 15 June 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Alexandra, Heather (18 October 2016). "Fans Translate Rare Japanese Zelda Game, Now Everyone Can Play It". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- Linneman, John (26 January 2020). "Cooly Skunk: how a lost Super NES game was miraculously recovered via satellite download". Eurogamer. Gamer Network. Retrieved 29 January 2020.