Saqqara

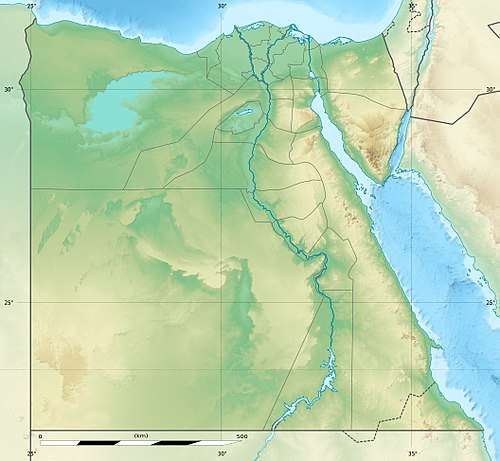

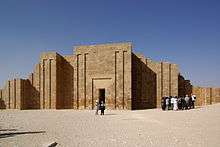

Saqqara (Arabic: سقارة, Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [sɑʔˈʔɑːɾɑ]), also spelled Sakkara or Saccara in English /səˈkɑːrə/, is a vast, ancient burial ground in Egypt, serving as the necropolis for the Ancient Egyptian capital, Memphis.[1] Saqqara features numerous pyramids, including the world-famous Step pyramid of Djoser, sometimes referred to as the Step Tomb due to its rectangular base, as well as a number of mastabas (Arabic word meaning 'bench'). Located some 30 km (19 mi) south of modern-day Cairo, Saqqara covers an area of around 7 by 1.5 km (4.35 by 0.93 mi).

سقارة | |

The stepped Pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara | |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Location | Giza Governorate, Egypt |

|---|---|

| Region | Lower Egypt |

| Coordinates | 29°52′16″N 31°12′59″E |

| Type | Necropolis |

| History | |

| Periods | Early Dynastic Period to Middle Ages |

| Site notes | |

| Part of | "Pyramid fields from Giza to Dahshur" part of Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur |

| Includes |

|

| Criteria | Cultural: (i), (iii), (vi) |

| Reference | 86-002 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd session) |

| Area | 16,203.36 ha (62.5615 sq mi) |

At Saqqara, the oldest complete stone building complex known in history was built: Djoser's step pyramid, built during the Third Dynasty. Another 16 Egyptian kings built pyramids at Saqqara, which are now in various states of preservation or dilapidation. High officials added private funeral monuments to this necropolis during the entire pharaonic period. It remained an important complex for non-royal burials and cult ceremonies for more than 3,000 years, well into Ptolemaic and Roman times.

North of the area known as Saqqara lies Abusir, and south lies Dahshur. The area running from Giza to Dahshur has been used as a necropolis by the inhabitants of Memphis at different times, and it was designated as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1979.[2] Some scholars believe that the name Saqqara is not derived from the ancient Egyptian funerary deity, Sokar, but supposedly, from a local Berber Tribe called Beni Saqqar.[3]

History

Early Dynastic

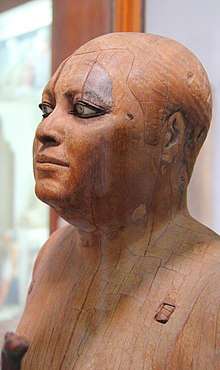

The earliest burials of nobles can be traced back to the First Dynasty, at the northern side of the Saqqara plateau. During this time, the royal burial ground was at Abydos. The first royal burials at Saqqara, comprising underground galleries, date to the Second Dynasty. The last Second Dynasty king, Khasekhemwy, was buried in his tomb at Abydos, but also built a funerary monument at Saqqara consisting of a large rectangular enclosure, known as Gisr el-Mudir. It probably inspired the monumental enclosure wall around the Step Pyramid complex. Djoser's funerary complex, built by the royal architect Imhotep, further comprises a large number of dummy buildings and a secondary mastaba (the so-called 'Southern Tomb'). French architect and Egyptologist Jean-Philippe Lauer spent the greater part of his life excavating and restoring Djoser's funerary complex.

Early Dynastic monuments

- tomb of king Hotepsekhemwy or Raneb

- tomb of king Nynetjer

- Buried Pyramid, funerary complex of king Sekhemkhet

- Gisr el-Mudir, funerary complex of king Khasekhemwy

- Step Pyramid, funerary complex of king Djoser

Old Kingdom

Nearly all Fourth Dynasty kings chose a different location for their pyramids. During the second half of the Old Kingdom, under the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties, Saqqara was again the royal burial ground. The Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pyramids are not built wholly of massive stone blocks, but instead with a core consisting of rubble. Consequently, they are less well preserved than the world-famous pyramids built by the Fourth Dynasty kings at Giza. Unas, the last ruler of the Fifth Dynasty, was the first king to adorn the chambers in his pyramid with Pyramid Texts. During the Old Kingdom, it was customary for courtiers to be buried in mastaba tombs close to the pyramid of their king. Thus, clusters of private tombs were formed in Saqqara around the pyramid complexes of Unas and Teti.

Old Kingdom monuments

- Mastabat al-Fir'aun, tomb of king Shepseskaf (Dynasty Four)

- Pyramid of Userkaf of the Fifth Dynasty

- Pyramid of Djedkare Isesi

- Pyramid of king Menkauhor

- Mastaba of Ti

- Mastaba of the Two Brothers (Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum)

- Pyramid of Unas

- Mastaba of Ptahhotep

- Pyramid of Teti (Dynasty Six)

- Mastaba of Mereruka

- Mastaba of Kagemni

- Mastaba of Akhethetep

- Pyramid of Pepi I

- Pyramid of Merenre

- Pyramid complex of king Pepi II Neferkare

- Tomb of Perneb (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York)

Middle Kingdom

From the Middle Kingdom onward, Memphis was no longer the capital of the country, and kings built their funerary complexes elsewhere. Few private monuments from this period have been found at Saqqara.

Second Intermediate Period monuments

New Kingdom

During the New Kingdom Memphis was an important administrative and military centre, being the capital after the Amaran Period. From the Eighteenth Dynasty onward many high officials built tombs at Saqqara. While still a general, Horemheb built a large tomb here, although he later was buried as pharaoh in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes. Other important tombs belong to the vizier Aperel, the vizier Neferrenpet, the artist Thutmose, and the wet-nurse of Tutankhamun, Maia.

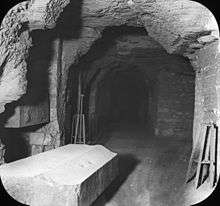

Many monuments from earlier periods were still standing, but dilapidated by this period. Prince Khaemweset, son of Pharaoh Ramesses II, made repairs to buildings at Saqqara. Among other things, he restored the Pyramid of Unas and added an inscription to its south face to commemorate the restoration. He enlarged the Serapeum, the burial site of the mummified Apis bulls, and was later buried in the catacombs. The Serapeum, containing one undisturbed interment of an Apis bull and the tomb of Khaemweset, were rediscovered by the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette in 1851.

New Kingdom monuments

- Several clusters of tombs of high officials, among which the tombs of Horemheb and of Maya and Merit. Reliefs and statues from these two tombs are on display in the National Museum of Antiquities at Leiden, the Netherlands, and in the British Museum, London.

After the New Kingdom

During the periods after the New Kingdom, when several cities in the Delta served as capital of Egypt, Saqqara remained in use as a burial ground for nobles. Moreover, the area became an important destination for pilgrims to a number of cult centres. Activities sprang up around the Serapeum, and extensive underground galleries were cut into the rock as burial sites for large numbers of mummified ibises, baboons, cats, dogs, and falcons.

Monuments of the Late Period, the Graeco-Roman and later periods

- Several shaft tombs of officials of the Late Period

- Serapeum (the larger part dating to the Ptolemaeic Period)

- The so-called 'Philosophers circle', a monument to important Greek thinkers and poets, consisting of statues of Hesiod, Homer, Pindar, Plato, and others (Ptolemaeic)

- Several Coptic monasteries, among which the Monastery of Apa Jeremias (Byzantine and Early Islamic Periods)

Site looting during 2011 protests

Saqqara and the surrounding areas of Abusir and Dahshur suffered damage by looters during the 2011 Egyptian protests. Store rooms were broken into, but the monuments were mostly unharmed.[4][5]

Recent Discoveries

During routine excavations in 2011 at the dog catacomb in Saqqara necropolis, an excavation team led by Salima Ikram, and an international team of researchers led by Paul Nicholson of Cardiff University, uncovered almost eight million animal mummies at the burial site next to the sacred temple of Anubis. It is thought that the mummified animals, mostly dogs, were intended to pass on the prayers of their owners to their deities.[6]

"You don't get 8 million mummies without having puppy farms," she says. "And some of these dogs were killed deliberately so that they could be offered. So for us, that seems really heartless. But for the Egyptians, they felt that the dogs were going straight up to join the eternal pack with Anubis. And so they were going off to a better thing" said Salima Ikram.[7][8]

In July 2018, German-Egyptian researchers’ team head by Dr. Ramadan Badry Hussein and University of Tübingen reported the discovery of an extremely rare gilded burial mask which probably dates from Saite-Persian period in a partly damaged wooden coffin. The last time a similar mask was found, was in 1939.[9] The eyes were covered with obsidian, calcite, and black hued gemstone possibly onyx. “The finding of this mask could be called a sensation. Very few masks of precious metal have been preserved to the present day, because the tombs of most Ancient Egyptian dignitaries were looted in ancient times.” said Hussein.[10][11] In November, 2018, seven ancient Egyptian tombs were located at the ancient necropolis of Saqqara by an Egyptian archaeological mission, with a collection of scarab and cat mummies, dating back to the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.[12] According to the former minister Khaled el-Enany, three of the tombs were used for cats some dating back more than 6,000 years, while one of four other sarcophagi revealed at the site was unsealed. Within the remains of cat mummies were unearthed gilded and 100 wooden statues of cats and one in bronze dedicated to the cat goddess named Bastet. In addition, funerary items dating back to the 12th Dynasty were found besides the skeletal remains of cats.[13][14][15][16]

In mid-December 2018 the Egyptian government announced the discovery at Saqqara of a previously unknown 4,400-year-old tomb, containing paintings and more than fifty sculptures. It belongs to Wahtye, a high-ranking priest who served under King Neferirkare Kakai during the Fifth Dynasty.[17] The tomb also contains five shafts that may lead to a sarcophagus below.[18]

On April 13, 2019, an expedition led by Department Member of Czech Institute of Egyptology Mohamed Megahed discovered a 4,000-year-old tomb near Egypt's Saqqara Necropolis. Archaeologists confirmed that the tomb belonged to an influential person named 'Khuwy' who lived in Egypt during the 5th dynasty.[19][20][21][22]

“The L-shaped Khuwy tomb starts with a small corridor heading downwards into an antechamber and from there a larger chamber with painted reliefs depicting the tomb owner seated at an offerings table” reported the head of the excavation team Mohamed Megahed.[20]

According to CNN, it is surprising that there are some paintings that maintained their brightness over a long time in the tomb mainly made of white limestone bricks. Another interesting fact is that the tomb had a tunnel entrance generally typical for pyramids.[20]

Archaeologists say that there might be a connection between Khuwy and Pharaoh because the mausoleum was found near the pyramid of Egyptian Pharaoh Djedkare Isesi, who ruled during that time.[19][21][20][22]

In June 2019, several hundred cache of mummies dating 2,000 years back were found by a team of Polish archaeologists led by Dr. Kamil Kuraszkiewicz. Investigations were carried for almost two decades in the area near Djoser Pyramid, the oldest pyramid in the world. Archaeologists revealed the graves of noblemen from the period of the 6th dynasty, dating to the 24th-21st century BC and 500 graves of indigent people dating approximately to the 6th century BC - 1st century AD. The scientists identified that most of the bodies were poorly preserved and all organic materials, as well as, the wooden caskets decayed.[23][24][25]

Most of the mummies we discovered last season were very modest, they were only subjected to basic embalming treatments, wrapped in bandages and placed directly in pits dug in the sand

— Dr. Kamil Kuraszkiewicz.

References

- Fernandez, I., J. Becker, S. Gillies. "Places: 796289136 (Saqqarah)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 22, 2013.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Memphis and its Necropolis – the Pyramid Fields from Giza to Dahshur — UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- Graindorge, Catherine, "Sokar". In Redford, Donald B., (ed) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, vol. III, pp. 305–307

- "Egyptological Looting Database 2011".

- "Saqqara.nl".

- "Eight million dog mummies found in Saqqara".

- "Millions Of Mummified Dogs Found In Ancient Egyptian Catacombs". NPR.org. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- June 2015, Laura Geggel 18. "8 Million Dog Mummies Found in 'God of Death' Mass Grave". livescience.com. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Archaeologists Have Uncovered a Place Where The Ancient Egyptians Mummifed Their Dead, Science Alert, 16 July 2018

- "Researchers discover gilded mummy mask". HeritageDaily - Archaeology News. 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- M, Dattatreya; al (2018-07-16). "The Mummy With The Silver Gilded Mask - Discovered In Saqqara, Egypt". Realm of History. Retrieved 2020-05-10.

- "Ancient Egyptian tombs yield rare find of mummified scarab beetles". Reuters. 11 November 2018.

- "Dozens of Mummified Cats Found in 6,000-yr-old Egyptian Tombs". The Vintage News. 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- "Dozens of cat mummies found in 6,000-year-old tombs in Egypt". The Guardian.

- "Dozens of mummified cats, beetles unearthed in 6,000-year-old Egyptian tombs". Business Recorder. 2018-11-12. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- newscabal (2018-11-11). "Dozens of cat mummies found in 6,000-year-old tombs in Egypt". NEWSCABAL. Retrieved 2019-09-19.

- Brice-Saddler, Michael, Look inside a ‘one of a kind,' 4,400-year-old tomb discovered in Egypt, The Washington Post, December 16, 2018

- Owen Jarus (December 15, 2018). "4,400-Year-Old Tomb of 'Divine Inspector' with Hidden Shafts Discovered in Egypt". Live Science. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

Wahtye was a high-ranking priest who carried the title of divine inspector, said Mostafa Waziri, the general secretary of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities who led the Egyptian team that discovered the tomb... Several other discoveries have been made this year at Saqqara. They include a 3,300-year-old tomb of a high general, a burial ground containing a 2,500-year-old mummy wearing a silver face mask gilded with gold and a tomb complex that has more over 100 cat statues.

- "Newly Discovered 4,000-Year Old Egyptian Tomb Stuns Archaeologists". Geek.com. 2019-04-15. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Guy, Jack (2019-04-15). "Colorful tomb puzzles Egypt archaeologists". CNN Travel. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- Earl, Jennifer (2019-04-15). "Discovery of Egyptian dignitary's 4,000-year-old colorful tomb stuns archaeologists". Fox News. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- "Egypt: Vivid 4,300-year-old tomb belonging to Fifth Dynasty senior official unveiled". Sky News. Retrieved 2019-04-23.

- S.A, Telewizja Polska. "Polish archeologists uncover Egyptian mummies". polandin.com. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "Dozens of mummies discovered by Polish archaeologists next to the world`s oldest pyramid". Science in Poland. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

- "Dozens of mummies dating back 2,000 years found next to world's oldest pyramid". www.thefirstnews.com. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Saqqara. |