Sandy Amorós

Edmundo "Sandy" Amorós Isasi (January 30, 1930 – June 27, 1992) was a Cuban left fielder in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers and Detroit Tigers. Amorós was born in Havana. He both batted and threw left-handed, and was listed as 5 feet 7 inches (1.70 m) tall and 170 pounds (77 kg). Dodgers scout Al Campanis signed him in 1951, struck by the small man's speed. Sandy played for the New York Cubans of the Negro Leagues in 1950.[1]

| Sandy Amorós | |||

|---|---|---|---|

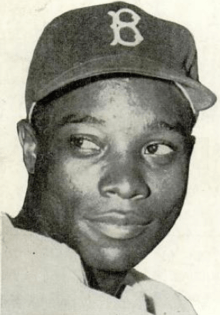

Amorós in 1954 | |||

| Left fielder | |||

| Born: January 30, 1930 Havana, Cuba | |||

| Died: June 27, 1992 (aged 62) Miami, Florida | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| August 22, 1952, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 2, 1960, for the Detroit Tigers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .255 | ||

| Home runs | 43 | ||

| Runs batted in | 180 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's baseball | ||

| Representing | ||

| Central American and Caribbean Games | ||

| 1950 Guatemala City | Team | |

Career

Amorós, nicknamed for his resemblance to boxing champ Sandy Saddler, had a brief but hugely underrated period of his Major League career. From 1954–57, his value to the Brooklyn Dodgers as a hitter was remarkable. This was not understood at the time partly because Amorós was overshadowed by Dodgers outfield stars like Duke Snider, partly because of Amorós's skin color, personality and nation of origin. But mostly he was underrated because the concept of On Base Percentage (OBP) was not yet a part of player evaluations. Amorós's batting averages were mediocre but, because he drew a large number of walks, his on base percentages between 1954 and 1957 were .353, .347, .385 and .399.

The defining moment of Amorós' career with the Brooklyn Dodgers was one of the memorable events in World Series history. It was the sixth inning of the decisive Game 7 of the 1955 World Series. The Dodgers had never won a World Series and were now trying to hold a 2–0 lead against their perennial rivals, the New York Yankees. The left-handed Amorós came into the game that inning as a defensive replacement, as the right-handed throwing Jim Gilliam moved from left field to second base in place of Don Zimmer. The first two batters in the inning reached base and Yogi Berra came to the plate. Berra, notorious for swinging at pitches outside the strike zone, hit an opposite-field shot toward the left field corner that looked to be a sure double, as the Brooklyn outfield had just shifted to the right. Amorós seemingly came out of nowhere, extended his gloved right hand to catch the ball and immediately skidded to a halt to avoid crashing into the fence near Yankee Stadium's 301 distance marker in the left field corner. He then threw to the relay man, shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who in turn threw to first baseman Gil Hodges, doubling Gil McDougald off first; Hank Bauer grounded out to end the inning.

Life in Cuba and the United States

Amorós' last season in the majors was 1960, after which he fell on hard times, largely because he came into conflict with Fidel Castro by refusing to take the manager's job at Castro's request for the Cuban National Team. He lost a $30,000 ranch he had owned for a number of years.

As author Roberto González Echevarría notes in his book The Pride of Havana (1999), "For many players, the collapse of the Cuban League had tragic consequences. The diaspora began. Amorós, for instance, returned to Cuba to find his property confiscated by the new Socialist government of Fidel Castro. Sandy could no longer leave Cuba for many years, during which time he became increasingly dependent on others for his needs. When he eventually was given permission to leave, the Dodgers put him on their roster for the few days he needed for his pension."

It was 1967 when Castro finally allowed Amorós to leave for the United States. After the Dodgers act of kindness of always looking out for those players considered part of the Dodger family, it became ironic Amorós would then move to Elton Avenue in the South Bronx not too far from Yankee Stadium where he made that famous catch in the 1955 World Series. Later that year, his wife divorced him.

Sandy lost touch with everyone in the Cuban community, especially all those individuals he thought were his friends. As a result of moving to the South Bronx, Sandy was immediately embraced by the local Puerto Rican community. There he became active in supporting Herman Badillo a politician who had been a borough president, United States Representative, and candidate for Mayor of New York City. He was the first Puerto Rican to be elected to these posts and be a mayoral candidate in the continental United States. A few years later, Sandy wanted something else. So in 1977, he moved to Central Florida to live with his best friend, Victor Germain from Puerto Rico, who lived in the South Bronx and later moved to Tampa in search of a better quality of life for he and his family.

Sandy lived comfortably in Clair-Mel City, a section of Tampa, with the Germain family for many years attending functions in his honor as the man who made it possible for Brooklyn to win its only World Series title.

After receiving an increase in his pension from Major League Baseball Sandy moved out on his own where he eventually developed an alcohol problem which later led to ill health (diabetes) and a life of poverty. He lost his best friend in 1986, then lost part of his left leg in 1987 to circulatory problems and gangrene where, at that time, old teammates and then the Baseball Assistance Program (BAT) gave him a helping hand.

Five years later, at the age of 62, Sandy died from pneumonia, in Miami, Florida.

He had been scheduled to travel to Brooklyn for a day in his honor and an appearance with Yogi Berra at a baseball-card show.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Sandy Amorós at Find a Grave