John Smith (President of Rhode Island)

John Smith (died 1663) was an early colonial settler and President of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He lived in Boston, but was later an inhabitant of Warwick in the Rhode Island colony where he was a merchant, stonemason, and served as assistant. In 1649 he was selected to be President of the colony, then consisting of four towns. In 1652 he was once again chosen President, but the two towns on Rhode Island (Newport and Portsmouth) had been pulled out of the joint colony, so he only presided over the towns of Providence and Warwick. An important piece of legislation enacted during this second term in 1652 abolished the slavery of African Americans, the first such law in North America.

John Smith | |

|---|---|

| 3rd President of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations | |

| In office 1649–1650 | |

| Preceded by | Jeremy Clarke |

| Succeeded by | Nicholas Easton |

| 6th President of Providence and Warwick | |

| In office 1652–1653 | |

| Preceded by | Samuel Gorton |

| Succeeded by | Gregory Dexter |

| Personal details | |

| Died | July 1663 Warwick, Rhode Island |

| Spouse(s) | Ann |

| Occupation | Stonemason, merchant, assistant, president, commissioner |

Early career

John Smith is first positively seen in the public record in June 1648 when he is listed as an inhabitant of Warwick in the Rhode Island colony.[1] While the historian Thomas W. Bicknell echoes James Savage in stating that Smith sailed from England in 1631 or 1632, first settling in Salem in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, evidence that the John Smith of Salem is the same as the President John Smith of Warwick is lacking, and recent research does not show a definitive connection.[2][3] However, the subject did reside in Boston before coming to Warwick as stated in a 1649 letter written by Roger Williams to Massachusetts Bay magistrate John Winthrop.[1] Smith was a shopkeeper or merchant, a stonemason, and an assistant from Warwick in 1648. The same year he was also the head of a "General Court of Trial" for the town of Warwick which apparently was active when the primary court was out of session.[2] In May 1649 he was chosen to be the President of the four-town colony, and served in this capacity for one year.[1]

Three years later, after William Coddington pulled the towns of Newport and Portsmouth from the union with Providence and Warwick, Smith was once again selected as the President, but this time only presiding over the latter two towns.[1] During this second term as president a landmark piece of legislation against negro slavery was passed in 1652, the first legislation covering the matter of general human servitude enacted on the North American continent.[4] The law stated, "let it be ordered, that no blacke mankind or white being forced by covenant bond, or otherwise, to serve any man or his assighnes longer than ten yeares, or untill they come to bee twentie four yeares of age, if they bee taken in under fourteen, from the time of their cominge within the liberties of this Colonie. And at the end of terme of ten yeares to sett them free, as the manner is with the English servants..."[4] The legislation was amended in 1676, adding that no Indian shall be a slave.[4]

Another piece of legislation during Smith's tenure concerned speaking evil of the magistrates and for uttering libellous and slanderous words; such outspokenness had come into common use, and was becoming a problem for colonial leaders.[4] Twice when Smith was elected as President, he declined the position, and this prompted the General Assembly to order that "if a President elected shall refuse to serve in that Generall office, that then he shall pay a fine of ten pounds."[5]

Later life

After having served as the presiding officer of the colony, Smith appears on a list of freeman of Warwick in 1655, and the same year was ordered to "cast up what damage is due to the Indians, and place every man's share according to his proportion and gather it up...."[1] If anyone refused to pay his share, then he would be served with a warrant from the town Deputy.[1]

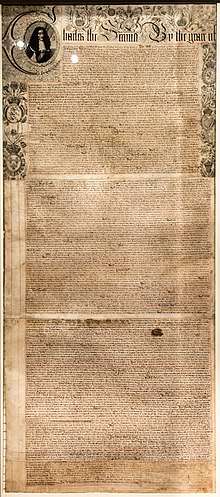

In late 1657, the subject John Smith brought an action of debt against another John Smith, a mason, living in Warwick. From 1658 to 1663 Smith was a commissioner from Warwick, serving in this capacity until his death. He was named as one of the ten Assistants in the Royal Charter of 1663, which would become the basis for Rhode Island's government for nearly two centuries. The inventory of Smith's estate was presented on 11 August 1663, suggesting that he had died a few weeks prior to that time. The inventory shows a fairly ample estate, valued at more than 600 pounds.[1] Being a stonemason, Smith had built a stone house in Warwick as his dwelling place, called "The Old Stone Castle."[6] When the Indians burned Warwick in 1663, this was the only house that survived. The house came into the possession of the Greene family, and was eventually demolished in 1779.[6]

Family

Smith married Ann Collins whose maiden name is not known, and by her Collins husband she had two children, Ann and Elizur.[1] Smith had no known children.[1]

See also

References

- Austin 1887, p. 184.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 996.

- Anderson 1995, pp. 1693-1694.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 997.

- Bicknell 1920, pp. 997–998.

- Bicknell 1920, p. 998.

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620–1633. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-120-9. OCLC 42469253.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Austin, John Osborne (1887). Genealogical Dictionary of Rhode Island. Albany, New York: J. Munsell's Sons. ISBN 978-0-8063-0006-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bicknell, Thomas Williams (1920). The History of the State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Vol.3. New York: The American Historical Society. pp. 996–998.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)