Sabratha

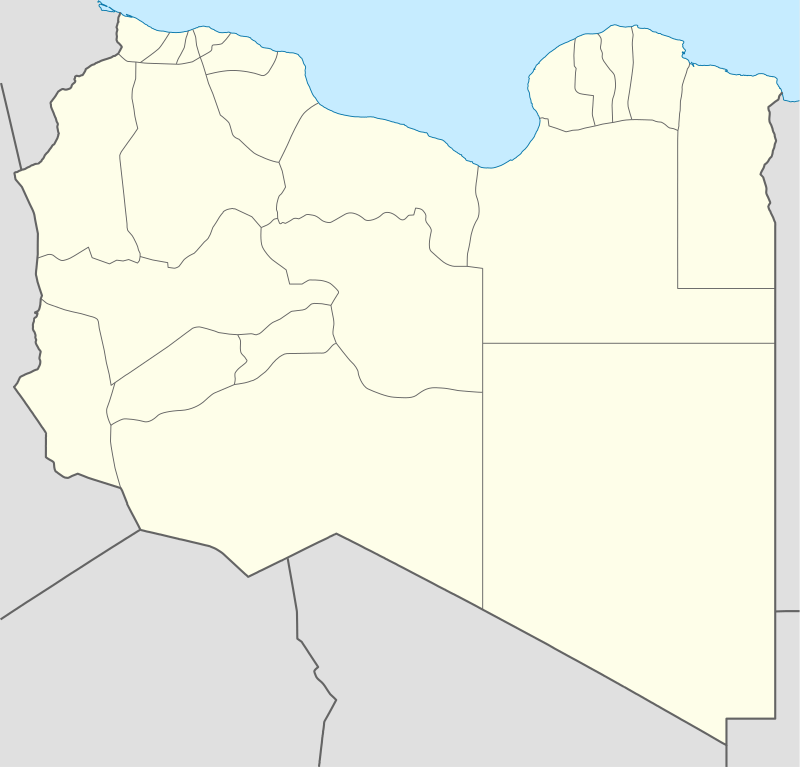

Sabratha, Sabratah or Siburata (Arabic: صبراتة), in the Zawiya District[2] of Libya, was the westernmost of the ancient "three cities" of Roman Tripolis, alongside Oea and Lepcis Magna. From 2001 to 2007 it was the capital of the former Sabratha wa Sorman District. It lies on the Mediterranean coast about 70 km (43 mi) west of modern Tripoli.[3] The extant archaeological site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.

Sabratha صبراتة | |

|---|---|

Town | |

| Sabratha or Subrata | |

Theater of Sabratha | |

Sabratha Location in Libya | |

| Coordinates: 32°47′32″N 12°29′3″E | |

| Country | Libya |

| Region | Tripolitania |

| District | Zawiya |

| Elevation | 30 ft (10 m) |

| Population (2004)[1] | |

| • Total | 102,038 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Website | sabratha.gov.ly |

| Official name | Archaeological Site of Sabratha |

| Includes | Theater at Sabratha |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iii) |

| Reference | 184 |

| Inscription | 1982 (6th session) |

| Endangered | 2016–... |

Ancient Sabratha

Sabratha's port was established, perhaps about 500 BCE, as the Phoenician trading-post of Tsabratan (Punic: 𐤑𐤁𐤓𐤕𐤍, ṣbrtn, or 𐤑𐤁𐤓𐤕𐤏𐤍, ṣbrtʿn).[4][5] This seems to have been a Berber name,[6] suggesting a preëxisting native settlement. The port served as a Phoenician outlet for the products of the African hinterland. Greeks called it also Abrotonon (Ancient Greek: Ἀβρότονον).[7][8][9] After the demise of Phoenicia, Sabratha fell under the sphere of influence of Carthage.

Following the Punic Wars, Sabratha became part of the short-lived Numidian kingdom of Massinissa before this was annexed to the Roman Republic as the province of Africa Nova in the 1st century BC. It was subsequently romanized and rebuilt in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. The Emperor Septimius Severus was born nearby in Leptis Magna, and Sabratha reached its monumental peak during the rule of the Severans, when it nearly doubled in size. The city was badly damaged by earthquakes during the 4th century, particularly the quake of 365. It fell under control of the Vandal kingdom in the 5th century, with large parts of the city being abandoned. It enjoyed a small revival under Byzantine rule, when multiple churches and a defensive wall (although only enclosing a small portion of the city) were erected. The town was site of a bishopric.[10] Within a hundred years of the Muslim invasion of the Maghreb, trade had shifted to other ports and Sabratha dwindled to a village.

Archaeological site

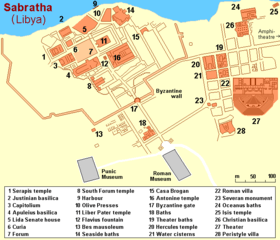

Sabratha has been the place of several excavation campaings from 1921 onwards, mainly by Italian archaeologists. It was also excavated by a British team directed by Kathleen Kenyon and John Ward-Perkins between 1948 and 1951.[11] Besides its Theater at Sabratha that retains its three-storey architectural backdrop, Sabratha has temples dedicated to Liber Pater, Serapis and Isis. There is a Christian basilica of the time of Justinian and also remnants of some of the mosaic floors that enriched elite dwellings of Roman North Africa (for example, at the Villa Sileen, near Khoms). However, these are most clearly preserved in the colored patterns of the seaward (or Forum) baths, directly overlooking the shore, and in the black and white floors of the theater baths.

There is an adjacent museum containing some treasures from Sabratha, but others can be seen in the national museum in Tripoli.

In 1943, during the Second World War, archaeologist Max Mallowan, husband of novelist Agatha Christie, was based at Sabratha as an assistant to the Senior Civil Affairs Officer of the Western Province of Tripolitania. His main task was to oversee the allocation of grain rations, but it was, in the words of Christie's biographer, a "glorious attachment", during which Mallowan lived in an Italian villa with a patio overlooking the sea and dined on fresh tunny fish and olives.[12]

Erosion and weathering damage [ April 2016 report ]

According to an April, 2016 report, due to soft soil composition and the nature of the coast of Sabratha, which is mostly made up of soft rock and sand, the Ruins of Sabratha are undergoing dangerous periods of coastal erosion. The public baths, olive press building and 'harbor' can be observed as being most damaged as the buildings have crumbled due to storms and unsettled seas. As the most common building material in Sabratah, calcarenite, is highly susceptible to physical, chemical and biological weathering (particularly marine spray), the long-term conservation of the monuments is endangered.[13] Rising sea levels can also compromise the integrity of the site.[14]

This erosion of the coast of Ancient Sabratha can be seen yearly with significant differences in beach layout and recent crumbled buildings. Breakwaters set in the vicinity of the harbor and olive press are inadequate and too small to efficiently protect the Ancient City of Sabratha.

Modern Sabratha

The city is home to Sabratha University. Wefaq Sabratha is the football club, playing at Sabratha Stadium.

Climate

Sabratha has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh).

| Climate data for Sabratha | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.7 (74.7) |

25.9 (78.6) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.1 (89.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

24.9 (76.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

7.9 (46.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

13.1 (55.6) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.0 (66.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

21.1 (70.0) |

20.3 (68.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.1 (46.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 45 (1.8) |

26 (1.0) |

17 (0.7) |

11 (0.4) |

4 (0.2) |

1 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

8 (0.3) |

23 (0.9) |

33 (1.3) |

51 (2.0) |

219 (8.6) |

| Source: Climate-data.org | |||||||||||||

Images

Panorama

Panoramic image of a part of the archaeological site

Panoramic image of a part of the archaeological site- Panoramic image of the theater of the archaeological site

WWII Aerial photo of theater

WWII Aerial photo of theater

Archaeological site

- Theater in Sabratha city 2nd century CE

- Theater

View of the Sabratha theater

View of the Sabratha theater- Marble facing on the wall of theater

- One of many ways inside of theater

- Inside ways of theater

- Ruins of theater

- Theater

- Theater

- One the few entries to theater

- Theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- Bas-Relief (on bottom of stage), theater

- High relief, theater

- High relief, theater

- Theater

- Plinth and capital of columns, theater

- Capital of column, theater

- Theater

- Theater

- Stairs to the stage, theater

- Theater

- The gate, theater

- Architrave and capital, theater

- Back side of theater

- The gate decor element, theater

- Nymphaeum

- Nymphaeum

- Seaside therms

- Latrines

- Latrines

- Сouncil chamber

- Curia 4 CE

- Mosaic in the Peristyle house

- Mosaic in the Peristyle house

- Peristyle house

- Peristyle house

- Seawards bath mosaic

- Inscription in front of the Capitolium, 2nd century BCE

- Basilica of Apuleus, Byzantine baptistery

- Basilica of Apuleus, Pylone

- Fontain of Flavius Tullus at the Antonine Temple

- Podium at the Antonine Temple

- Antonine Temple

- Podium at the Antonine Temple

.jpg) Mausoleum of Bes, 2nd century BCE

Mausoleum of Bes, 2nd century BCE

Museum

- Torso of the Emperor Vespasian, or his son Titus. 1st century Museum courtyard

- Mosaic. Museum

- Mosaic. Museum

- Mosaic. Museum

- Mosaic from theater baths. Museum."Salvom Lavisse" - "Washing it's well!"

- Mosaic. Museum

- Mosaic. Museum

- Head. Museum

- Marble figure of a satyr. From the Forum. Museum

- Bust of Jupiter. From the Temple of Jupiter. Museum

- Bust of Goddess Concordia from the Temple of Jupiter. Museum

- Marble candelabrum showing Orpheus and the animals. From Theatre Baths 3rd century Museum

- Head. Museum

- Decor element of Insula (house). Museum

- Mosaic. Museum

- Basilica of Justinian reconstructed in the Site Museum

References

Citations

- Wolfram Alpha

- شعبيات الجماهيرية العظمى – Sha'biyat of Great Jamahiriya, accessed 20 July 2009, in Arabic

- Agence France-Presse (January 31, 2017). "Libyan coastguard intercepts 700 migrants". The Nation. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017.

“The coastguard intercepted 700 migrants on board two wooden boats on Friday three nautical miles from the town of Sabratha,” some 70 kilometres (40 miles) west of Tripoli, coastguard spokesman General Ayoub Qassem told AFP.

- Ghaki (2015), p. 67.

- Head & al. (1911).

- Septimus Severus page 2

- Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, §A9.7

- Strabo, Geography, §17.3.18

- Pseudo Scylax, Periplous, §110

- Francois Decret, Early Christianity in North Africa(James Clarke & Co, 2011) p83

- Kenrick, Philip M. (2009). Tripolitania. Society for Libyan Studies (London, England). London: Society for Libyan Studies. ISBN 978-1-900971-08-9. OCLC 320789516.

- Janet Morgan (1984) Agatha Christie: a Biography

- El-Shahat, Adam; Minas, Haithem; Khomiara, Sadek (March 2014). "Weathering of Calcarenite Monuments at Roman and Byzantine Archaeological Sites at Sabratha, Northwestern Libya: A Pilot Study". African Archaeological Review. 31 (1): 45–58. doi:10.1007/s10437-014-9153-8. ISSN 0263-0338.

- Reimann, Lena; Vafeidis, Athanasios T.; Brown, Sally; Hinkel, Jochen; Tol, Richard S. J. (2018-10-16). "Mediterranean UNESCO World Heritage at risk from coastal flooding and erosion due to sea-level rise". Nature Communications. 9 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06645-9. ISSN 2041-1723.

Bibliography

- Ghaki, Mansour (2015), "Toponymie et Onomastique Libyques: L'Apport de l'Écriture Punique/Néopunique" (PDF), La Lingua nella Vita e la Vita della Lingua: Itinerari e Percorsi degli Studi Berberi, Studi Africanistici: Quaderni di Studi Berberi e Libico-Berberi, No. 4, Naples: Unior, pp. 65–71, ISBN 978-88-6719-125-3, ISSN 2283-5636. (in French)

- Head, Barclay; et al. (1911), "Syrtica", Historia Numorum (2nd ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press, p. 875.

- Rodríguez López, María Isabel (2017). "The Relief Decorations of the Ancient Roman Theater: The Case of Sabratha". Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 42 (1–2): 17–31. ISSN 1522-7464.

Further reading

- Kenrick, Philip (1986) Excavations at Sabratha 1948-1951 Malet Street: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, ISBN 090776407X

- Matthews, Kenneth D. (1957) Cities in the Sand, Leptis Magna and Sabratha in Roman Africa University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, OCLC 414295

- Reynolds, Joyce M, et al. Inscriptions of Roman Tripolitania, first edition 1952 British School at Rome/second ed. 2009 King's College London.

- Ward, Philip (1970) Sabratha: A Guide for Visitors Oleander Press, Cambridge, UK, ISBN 0-902675-05-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sabratha. |

- UNESCO archaeological site of Sabratha

- Complete photo coverage of the archeological site

- Sabratha, image from the BSR Library and Archive digital collections. Ward-Perkins photographic collection

- LookLex article

- IRT chapter on history and epigraphy of Sabratha

- Pleiades Gazetteer entry on ancient Abrotonum/Sabratha