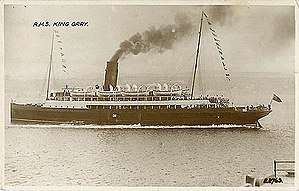

SS King Orry (1913)

TSS (RMS) King Orry (III) – the third ship in the history of the Company to bear the name – was a passenger steamer which served with the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company, until she was sunk during the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940.

RMS King Orry | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | King Orry |

| Owner: | 1913–1940: Isle of Man Steam Packet Company |

| Operator: | 1913–1940: Isle of Man Steam Packet Company. |

| Port of registry: | Douglas, Isle of Man |

| Builder: | Cammell Laird |

| Cost: | £96,000 |

| Yard number: | 789[1] |

| Launched: | 11 March 1913 |

| In service: | 1913 |

| Out of service: | 1940 |

| Identification: |

|

| Fate: | Sunk at Dunkirk 30 May 1940. |

| Status: | War Grave LAT:51°07'N LON:002°21'E.[3] |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Passenger Steamer |

| Tonnage: | 1,877 gross register tons (GRT) |

| Length: | 313 feet (95 m) |

| Beam: | 43 feet (13 m) |

| Depth: | 16 ft 11 in (5.16 m) |

| Ice class: | N/A |

| Installed power: | 9,400 shp (7,000 kW) |

| Propulsion: | Marine geared turbines developing 9,400 shp (7,000 kW) |

| Speed: | 21 knots (39 km/h) |

| Capacity: | 1,600 passengers |

| Crew: | 59 |

Construction and dimensions

King Orry was a ship, built by Cammell Laird at Birkenhead who also supplied her engines and boilers, at a cost of £96,000. She had a registered tonnage of 1,600 GRT; length 313 ft (95.4 m); a beam of 43 ft (13.1 m); depth 16'11" and with a design speed of 21 knots. King Orry had accommodation for 1,600 passengers, and a crew of 51.

King Orry was launched from Cammell Laird's Birkenhead shipyard on 11 March 1913.[4]

Service life

King Orry was the last ship built for the Steam Packet before the outbreak of the First World War, and represented another move forward in the marine engineering design of the Steam Packet steamers, for she was the first of the Company's ships to be built with geared turbines. This gave her a low propeller speed while keeping a high turbine speed. Her twin screws were driven by two single-reduction geared turbine engines developing 9,400 i.h.p.

King Orry entered service in 1913, making her maiden voyage on the Liverpool to Douglas route on 8 July that year, taking 3 hours 101⁄2 minutes to make the journey at an average speed of 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph).[5]

On Friday 17 July 1914, King Orry ran aground near Maughold, Isle of Man.[6] Under the command of Capt. Bridson, the King Orry had taken the place of the Ben-my-Chree (which had gone to Ardrossan) on the Douglas – Liverpool service, departing at 16:00hrs.[6] After coaling at Liverpool it was the Master’s intention to make passage direct to Ardrossan in order to bring holidaymakers to Douglas.[6] As she neared the Isle of Man, the King Orry ran into a bank of fog, which obscured the coast with the added complication that the Foghorn at Maughold Head Lighthouse could not be heard.[6] Whilst trying to re-set her course, the King Orry ran aground at Cornah (Cornaa, current spelling), on the north-east coast of the Isle of Man, approximately one mile south of Maughold Head.[6] News of the King Orry's plight was passed by wireless message to the Company’s Headquarters at Douglas by the Mona’s Queen,[6] which shortly passed near the scene inbound to Douglas from Ardrossan, and the Peel Castle and the Fenella were despatched to aid the King Orry.[6]

However two hours after grounding, the King Orry refloated on the rising tide, and then made her way to Douglas under her own power.[6] She was inspected by the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company’s Senior Marine Superintendent, who found only slight damage had been sustained, with only one or two plates being strained.[6] The following morning, King Orry sailed for Cammell Laird's dry dock at Birkenhead, for repairs to be undertaken, returning to service a week later.[6]

At the time of the grounding there were no passengers on board.[6]

She had only begun to establish herself within the Company's fleet, when she was requisitioned by the Admiralty at the outbreak of war in 1914.

First World War

King Orry saw service in both World Wars. She was fitted out as an Armed Boarding Vessel by Cammell Laird's in late November 1914, being fitted with an armament of two 4 inch (102 mm) guns.[7] She then made passage for Scapa Flow. There she spent her time on patrol, tending to the crews of stricken ships, challenging suspects, and putting prize crews aboard where appropriate.

On one occasion she sent men aboard a large vessel laden with 10,000 tons of wheat for Germany, and her prize crew took the vessel into Kirkwall. Then, diverted to patrol down the fringe of the German minefield off the Heligoland Bight, she challenged and boarded six ships in one day, and put a prize crew aboard an oil tanker which she then directed to the East Coast of England.

On 23 September 1915, King Orry collided with the destroyer Christopher, damaging the destroyer.[8]

In early June 1916, in response to intelligence that there would be a breakout by the German Merchant raider Möwe (and possibly also the German light cruiser Niobe), King Orry and the cruiser Donegal, both patrolling between Shetland and Norway, were ordered to support the armed merchant cruisers of the 10th Cruiser Squadron to intercept the German raider. While the 10th Cruiser Squadron were to patrol between Scotland and Iceland, King Orry and Donegal were to patrol near Muckle Flugga. No signs of the German ships were found by any of the patrols.[9]

After the Battle of Jutland, the Royal Navy was ordered to undergo intensive gunnery practice, and the King Orry turned to the business of target towing. She was well suited to this field of work, and was able to move the largest target at more than 12 knots. She even accompanied the Grand Fleet on exercises and acted as a 'repeating ship', that is, she transmitted the flagship signals to the battle squadron in line astern.

From 15 July 1916, King Orry and the Armed Boarding Vessel Dundee were disguised as merchant vessels, substantially changed in appearance, and sent to patrol off Norway, tasked with intercepting ships carrying contraband down the Scandinavian approach. On 17 July, King Orry seized the Norwegian steamer SS Britannic, carrying a cargo of magnetic iron ore from Kerkeness to Rotterdam, off Utvaer and sent her to Kirkwall under an armed guard.[10][11] Through fair weather and foul, but more usually foul in those northern waters, the King Orry stayed on station, suffering much storm damage, until she was ordered to Liverpool for repairs. She reached what had been once her regular port of call, but not before a shore battery at New Brighton had put shots across her bow when she failed to give a satisfactory answer to questioning signals.

She continued this record for the rest of the War.

When the German Empire's High Seas Fleet surrendered in the Firth of Forth on 21 November 1918, she was the sole representative of the British mercantile marine at the capitulation ceremony.

Admiral Beatty awarded her the place of honour in the middle of the centre line. So a small Manx steamer took station, surrounded by the victorious British Grand Fleet. It was symbolic of the work and sacrifice of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company ships during the First World War.

Inter-war period

After the Great War, the King Orry returned to the Steam Packet Company and resumed her service operating to the numerous ports then served by the Company.

King Orry′s most startling mishap in peacetime was her stranding near the Rock Lighthouse, New Brighton, while entering the Mersey on 19 August 1921. Over 1,300 people aboard her were rescued. She was refloated later that day.[12]

She was extensively overhauled in 1934, and then converted from coal to oil burning in 1939, when King Orry found herself once again at war.

Second World War

The King Orry carried some armament as an ABV (Armed Boarding Vessel). She was under the command of Cdr. J. Elliott RNR and was sent to Dunkirk as the plight of the British Expeditionary Force became stark. On her first visit to the stricken port, she succeeded in getting into the harbour where she embarked 1,131 soldiers. The ship cast off and made for Dover in the early hours of 27 May. Shore batteries off Calais opened up on her, hitting the ship at least twice, inflicting some damage, and there were casualties aboard. However, she was able to continue to Dover, where she docked just before noon.[13]

King Orry returned to Dunkirk in the late afternoon of 29 May. On passage, she survived a dive bombing attack, and made for the East Pier. A second and heavier attack was then made on her. Her steering gear was put out of action and all bridge instruments and woodwork were shattered. Even then, after colliding with the pier, the King Orry was still able to secure alongside. More attacks followed.

When darkness fell it was possible to see where she had been holed and to make temporary repairs. But in this condition it was apparent she was a danger to shipping that was already in enough danger. There was a risk she may founder in the approach channel to the harbour, but none-the-less after midnight she was ordered to leave and her commander succeeded in getting the badly damaged vessel clear of the harbour entrance.

Soon however, she began to list heavily to starboard. Her engine room started to flood and she was abandoned. Shortly after 02:00hrs, 30 May 1940, she sank. Other ships in the crowded and turbulent waters closed in and survivors, including the four Manx engineers, were picked up.

One of these little ships was the 'BYSTANDER' which prior to the beginning of WW2 was the tender to W.L.Stevenson's J-Class racing yacht 'Valsheda'. Captained by Lt. Cmdr. RNVR H. Miller, 99 souls: crew and evacuees from the bombed and sunk Isle of Man Steam Packet ferry KING ORRY, and soldiers from the shore were rescued. Her cook, Jesse Elton from Poole, who single-handedly swam to rescue 25 from KING ORRY eventually received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal from the King at Buckingham Palace.

The position of the wreck of King Orry is given as LAT:51°07'N LON:002°21'E.[14]

Operation Dynamo, whilst widely regarded as the Steam Packet's "finest hour", also saw its blackest day. Three vessels were lost from the fleet on 29 May; Mona's Queen, Fenella and King Orry.[15][16]

References

Notes

- http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?150

- Ships of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Company (Fred Henry) p. 66

- http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?150#150

- "Industrial and Trade Notes: Mersey and Manchester Ship Canal". The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect. Vol. 35. April 1913. p. 356.

- "The Fleets of the Mail Lines: The Isle of Man Steam Packet Company". The Marine Engineer and Naval Architect. Vol. 36. August 1913. p. 2.

- The Isle of Man Examiner. Saturday, 25 July 1914

- Dittmar and Colledge 1972, p. 123.

- Jellicoe 1919 p. 247.

- Naval Staff Monograph No. 33 1927, pp. 39–40.

- Jellicoe 1919 pp. 434–435.

- Naval Staff Monograph No. 33 1927, p. 74.

- "Wreck escapes by ladder". The Times (42804). London. 20 August 1921. col F, p. 8.

- Winser 1999, pp. 15, 90.

- http://www.wrecksite.eu/wreck.aspx?150#150

- "About Us". Steam Packet Co. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Isle of Man Weekly Times. 8 June 1940. Missing or empty

|title=(help) (article lists some crew names and photographs)

Bibliography

- Chappell, Connery (1980). Island Lifeline: History of the Isle of Man Steam Packet Co. Ltd, 1830-90. Prescot, Merseyside: T. Stephenson and Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-901314-20-X.

- Dittmar, F.J.; Colledge, J.J. (1972). British Warships 1914–1919. Shepperton, UK: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0380-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Handscombe, David (2006). King Orry 1913–1940. Ramsey, Isle of Man: Ferry Publications. ISBN 1871947812.

- Jellicoe, John (1919). The Grand Fleet 1914–16: Its Creation, Development and Work. London: Cassell and Company. OCLC 859842281.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Monograph No. 33: Home Waters Part VII: From June 1916 to November 1916 (PDF). Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). XVII. Naval Staff, Training and Staff Duties Division. 1927.

- Osborne, Richard; Spong, Harry & Grover, Tom (2007). Armed Merchant Cruisers 1878–1945. Windsor, UK: World Warship Society. ISBN 978-0-9543310-8-5.

- Winser, John de S. (1999). B.E.F. Ships before, at and after Dunkirk. Gravesend, UK: World Ship Society. ISBN 0-905617-91-6.

External links

![]()