SMS Carola

SMS Carola was the lead ship of the Carola class of steam corvettes built for the German Kaiserliche Marine (Imperial Navy) in the 1880s. Intended for service in the German colonial empire, the ship was designed with a combination of steam and sail power for extended range, and was equipped with a battery of ten 15-centimeter (5.9 in) guns. Carola was laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin in 1879, launched in November 1880, and completed in September 1881.

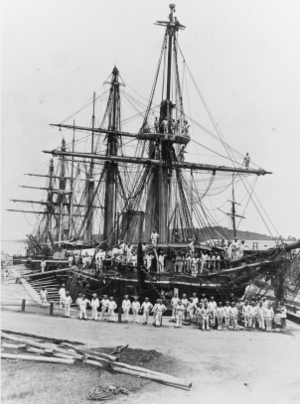

Carola and her sister ship Olga in Hong Kong in the 1880s | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Carola |

| Namesake: | Carola of Saxony |

| Builder: | AG Vulcan Stettin |

| Laid down: | 1879 |

| Launched: | 27 November 1880 |

| Commissioned: | 1 September 1881 |

| Decommissioned: | 10 January 1905 |

| Fate: | Broken up, 1906 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Carola-class corvette |

| Displacement: | Full load: 2,424 t (2,386 long tons) |

| Length: | 76.35 m (250 ft 6 in) |

| Beam: | 12.5 m (41 ft) |

| Draft: | 4.98 m (16 ft 4 in) |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | |

| Speed: | 13.7 knots (25.4 km/h; 15.8 mph) |

| Range: | 3,420 nautical miles (6,330 km; 3,940 mi) at 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph) |

| Crew: |

|

| Armament: |

|

Carola was sent abroad twice during her career, the first immediately after entering service in 1881 and lasting into 1883. She sailed to the central Pacific Ocean to protect German interests in Samoa and Melanesia and was the first German warship to reach what would become German Southwest Africa. Her second deployment came in 1886, and lasted into 1891; the tour saw Carola alternate between German East Africa and the central Pacific. During operations in the former from 1888 to 1890, she participated in anti-slave trade operations and helped suppress the Abushiri revolt.

After returning to Germany in 1891, Carola was converted into a gunnery training ship, as she was by then obsolete as a warship. She served in this capacity through the 1890s and early 1900s, before being decommissioned in 1905, sold the following year, and broken up for scrap.

Design

The six ships of the Carola class were ordered in the late 1870s to supplement Germany's fleet of cruising warships, which at that time relied on several ships that were twenty years old. Carola and her sister ships were intended to patrol Germany's colonial empire and safeguard German economic interests around the world.[1]

Carola was 76.35 meters (250 ft 6 in) long overall, with a beam of 12.5 m (41 ft) and a draft of 4.98 m (16 ft 4 in) forward. She displaced 2,424 metric tons (2,386 long tons) at full load. The ship's crew consisted of 10 officers and 246 enlisted men. She was powered by a single marine steam engine that drove one 2-bladed screw propeller, with steam provided by eight coal-fired fire-tube boilers, which gave her a top speed of 13.7 knots (25.4 km/h; 15.8 mph) at 2,367 metric horsepower (2,335 ihp). She had a cruising radius of 3,420 nautical miles (6,330 km; 3,940 mi) at a speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph). As built, Carola was equipped with a three-masted barque rig, but she had her rigging reduced in 1891.[2][3][4]

Carola was armed with a battery of ten 15 cm (5.9 in) 22-caliber (cal.) breech-loading guns and two 8.7 cm (3.4 in) 24-cal. guns. She also carried six 37 mm (1.5 in) Hotchkiss revolver cannons. The 15 cm guns were later reduced to six and then four guns, and the 8.7 cm guns were replaced with a pair of 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/35 guns, eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) SK L/30 guns, and two 5 cm (2 in) SK L/40 guns.[2][3]

Service history

Construction and first overseas deployment

Carola was laid down at the AG Vulcan shipyard in Stettin in late 1879 under the contract designation "E", denoting a new addition to the fleet.[5] She was launched on 27 November 1880,[2] and during the ceremony she was christened Carola in honor of Queen Carola of Saxony. After completing fitting-out work, Carola was commissioned on 1 September 1881 for sea trials, though these lasted just two weeks, as the ship was needed in the central Pacific Ocean to protect German interests in the region. Carola left Kiel on 18 October, bound for Australia; from there, she proceeded north to Apia in Samoa, where she relieved the gunboat Möwe on 15 April 1882. After arriving, Carola took the German consul in Samoa on a tour of the islands to meet with the Samoan chiefs Malietoa Laupepa and Tupua Tamasese Titimaea. She cruised to visit Tonga, New Zealand, and the Society Islands; in the latter archipelago, she helped suppress a fire in Papeete on the island of Tahiti.[5]

Carola returned to Apia, where she was joined by the gunboat Hyäne. The two vessels began a trip to the Bismarck Archipelago on 22 November. On the way, Carola independently visited Tuvalu and the Carteret Islands before rejoining Hyäne in Matupi Harbor. The ships proceeded to the Hermit Islands, where locals had murdered two Germans and nine native employees of a German company. Carola and Hyäne were ordered to punish those responsible for the killings. They sent landing parties ashore to track them down, but the murderers fled to another island. After an extensive search that involved destroying local farms and huts, the Germans captured two men who were involved in the killings; both were executed. The two ships returned to Matupi, and on 16 January 1883, Carola departed for Sydney, Australia, stopping in the Duke of York Islands on the way. She sailed to Buka Island to search for a French expedition that had gone missing, but she was unable to locate the explorers. She remained in Buka from 20 to 24 January in a previously unused harbor, which was named "Queen Carola Harbor" in honor of the ship's namesake.[6]

Carola thereafter returned to Sydney, where from 11 February to 19 March she was overhauled. She returned to Apia on 8 May, where she received orders to return to Germany. A week later, Hyäne arrived to relieve her, and Carola embarked the consul for a tour of Polynesia and Melanesia that concluded in Matupi in early August. She left the consul there and began the voyage home on 4 August. While in Cape Town, South Africa, Carola received the order to go to south western Africa, where merchant Adolf Lüderitz had recently acquired a strip of territory around Angra Pequena. She reached the bay there on 18 August, the first German warship to arrive in what became the colony of German South West Africa. Carola departed and arrived in Kiel on 1 November, where she was inspected by General Leo von Caprivi, the new Chief of the Kaiserliche Admiralität (Imperial Admiralty). The ship was then decommissioned.[7]

Second overseas deployment

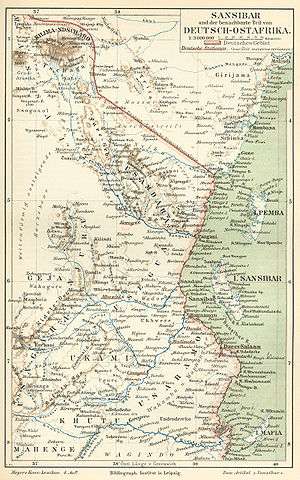

While out of service, Carola was equipped with a torpedo tube. She was recommissioned on 4 May 1886 for another deployment to the Pacific. She left on 17 May, transited the Suez Canal, and reached Singapore on 26 July. From there, she sailed to Hong Kong, where on 14 August she rendezvoused with the German overseas cruiser squadron, which consisted of her sister ship Olga and the corvette Bismarck, the flagship of Konteradmiral (KAdm—Rear Admiral) Eduard von Knorr. The three ships visited ports in Japan before departing East Asian waters for German East Africa; while en route, Carola had to stop in Singapore to repair her engines. She caught up with Bismarck and Olga in Zanzibar in late December. Germany had been granted a protectorate over Wituland, and Carola and Olga were tasked with surveying the coast. On 1 March 1887, the squadron received orders to return to the central Pacific, but before the ships could depart, they were temporarily redirected to Cape Town, where they were to await further orders, owing to a possibility of war with France. While they were waiting for the crisis to pass, Kapitän zur See (KzS—Captain at Sea) Karl Eduard Heusner arrived to replace Knorr, and Carola visited Angra Pequena again.[7]

On 15 April, Heusner arrived and the squadron was ordered to continue on their voyage to the Pacific on 7 May. They arrived in Sydney in early June, where they were overhauled between 9 June and 3 August. While there, men from Carola participated in a parade held for the celebration of British Queen Victoria's 40th year on the throne. After emerging from the Sydney dry dock, the three corvettes sailed to Samoa, where they were sent to punish Malietoa Laupepa for threatening German interests in the islands. Carola and Bismarck left Samoa for East Asia by way of the Bismarck Archipelago, where they visited several ports through May 1888. Heusner received the order to take his squadron back to East Africa; while in Singapore, Bismarck was ordered back to Germany, and her place as the squadron flagship was taken by Carola's sister Sophie. Carola was delayed in Singapore by engine troubles, which necessitated repairs that lasted until 26 June. The delay nevertheless allowed Olga time to rendezvous with the rest of the squadron while it waited for Carola to be ready for sea.[8]

In late-July, Carola went to Walvis Bay in German Southwest Africa, as rumors led the German government to believe a local revolt was planned. Nothing came in the colony, however, and Carola conducted a survey of the bay before returning to East Africa. While in Zanzibar in August, Heusner was recalled to Germany, and he was replaced by KAdm Karl August Deinhard aboard the corvette Leipzig, which took over the role of squadron flagship. The ships of the squadron were deployed to suppress the slave trade between central Africa, Zanzibar, and Arabia. On 6 November, Carola rejoined the squadron in Zanzibar before returning to operations in German East Africa. She bombarded rebels in Windi and sent marines ashore to attack them, and in the process captured a slave dhow with 78 slaves aboard, which she freed.[9] The crew from the dhow, which was not familiar with the black-painted German warship, thought it to be a British vessel, which were painted white. Believing that it posed no threat to them, they sailed close to Carola, allowing her to easily capture the slave ship.[10] In further operations around Bagamoyo, Carola's marines captured a pair of field guns used by rebel forces. Carola's marines took part in the occupation of Kunduchi on 27 March 1889, in a campaign led by Major Hermann Wissmann to suppress the Abushiri revolt.[9]

On 14 May, Carola left for Mahé in the Seychelles, as a significant number of her crew had contracted dysentery and needed time to rest and recover. Carola was back in East African waters on 11 June, when she took part in the search for three steam ships that had been sent to support Wissmann's forces. The ships were located in Kismayo on 15 June, and Carola escorted them to Zanzibar. She took part in the conquest of Pangani on 8 July and Tanga two days later. Carola went to Aden, where part of her crew were replaced. The ship's captain, Korvettenkapitän (Corvette Captain) Valette, served as the squadron commander from 13 August to 10 November, as he was the most senior officer in the area in the absence of Deinhard. Carola departed for Bombay on 10 November for an overhaul; she arrived back in Zanzibar on 17 February 1890. By this time, the cruiser squadron had been disbanded, and the new unprotected cruisers Schwalbe and Sperber had arrived in East Africa to strengthen German forces in the colony. Valette again served as the commander of naval operations on the ship's return.[9]

Carola returned to operations against rebels in East Africa, bombarding Kilwa Kisiwani on 28 March and sending troops ashore to capture the town between 1 and 4 May. She supported the capture of Lindi on 10 May. From 11 August to 17 September, she returned to Mahé for another rest period. On 9 October, she was present for the erecting of a monument to the soldiers killed in the fighting at Tanga. Toward the end of the year, Carola was recalled to Germany. She left Zanzibar on 20 January 1891 and was greeted by Kaiser Wilhelm II aboard the aviso Greif on arriving in Germany.[11]

Later career

Since she was by now obsolete as a warship, the Imperial Admiralty decided to convert Carola into a gunnery training ship as the older vessel Mars was no longer sufficient for the task, particularly because of the adoption of smokeless powder and quick-firing guns, which required more training than older-style guns. She was sent to the Kaiserliche Werft (Imperial Shipyard) in Danzig for the conversion. Her rigging was cut down and she was fitted with heavy military masts with fighting tops, her 15 cm guns were bolstered with shields to protect the crews, she received new 10.5 cm, 8.8 cm, and 5 cm guns, and the torpedo tube was removed. Carola returned to service in 1893 in her new role, initially operating in the Baltic Sea. She cruised either alone, with her tender Hay, an old gunboat, or with Mars, which was by then used to train artillery officers. She periodically also participated in maneuvers with the rest of the fleet.[4]

From 2 January 1894 to 15 March, Carola operated with a reduced crew. She had to go into dry dock in Kiel for repairs to her engines in September that year. She again had a reduced crew from 12 November 1894 to mid-February 1895, and again from 13 December 1895 to the end of February 1896. Carola and Mars served as target ships for the fleet in the North Sea in 1897, and she returned to gunnery training duties in 1898 and 1899. Her rudder was damaged in September 1899, necessitating repairs in Kiel. After an accident with Mars removed her from service in 1900, Carola had to take on her function as well as her own, though on 31 October, Olga returned to service as a gunnery training ship, reducing the burden on Carola. In 1902, Carola was overhauled at the Kaiserliche Werft in Wilhelmshaven. The following year, the naval artillery school was established in Sonderburg, and Carola was relocated there, operating in the waters off Alsen. The following year passed uneventfully, and on 10 January 1905, she was decommissioned and stricken from the naval register. She was sold the next year and broken up in Hamburg.[4]

Notes

- Sondhaus, pp. 116–117, 136–137.

- Gröner, p. 90.

- Gardiner, p. 252.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 173.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 170.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 170–171.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 171.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 171–172.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, p. 172.

- Lyne, p. 152.

- Hildebrand, Röhr, & Steinmetz, pp. 172–173.

References

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-133-5.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Hildebrand, Hans H.; Röhr, Albert & Steinmetz, Hans-Otto (1993). Die Deutschen Kriegsschiffe: Biographien: ein Spiegel der Marinegeschichte von 1815 bis zur Gegenwart (Band 2) [The German Warships: Biographies: A Reflection of Naval History from 1815 to the Present (Vol. 2)] (in German). Ratingen: Mundus Verlag. ISBN 9783782202107.

- Lyne, Robert Nunez (1905). Zanzibar in Contemporary Times: A Short History of the Southern East in the Nineteenth Century. London: Hurst and Blackett, Ltd.

- Sondhaus, Lawrence (1997). Preparing for Weltpolitik: German Sea Power Before the Tirpitz Era. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-745-7.