South Tyrol

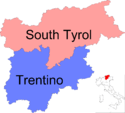

South Tyrol is an autonomous province in northern Italy, one of the two that make up the autonomous region of Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.[4] Its official trilingual denomination is Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol in German, Provincia autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige in Italian and Provinzia autonoma de Bulsan – Südtirol in Ladin, reflecting the three main language groups to which its population belongs. The province is the northernmost of Italy, the second largest, with an area of 7,400 square kilometres (2,857 sq mi) and has a total population of 531,178 inhabitants as of 2019. Its capital and largest city is Bolzano (German: Bozen; Ladin: Balsan or Bulsan).

Autonomous Province Bolzano – South Tyrol Autonome Provinz Bozen – Südtirol Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano – Alto Adige Provinzia Autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan – Südtirol | |

|---|---|

Autonomous province | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Map highlighting the location of the province of South Tyrol in Italy (in red) | |

| Country | |

| Region | Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol |

| Capital(s) | Bolzano |

| Comuni | 116 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Arno Kompatscher (SVP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,399.97 km2 (2,857.14 sq mi) |

| Population (1 January 2019) | |

| • Total | 531,178 |

| • Density | 72/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 39XXX |

| Telephone prefix | 0471, 0472, 0473, 0474 |

| Vehicle registration | BZ |

| GDP (nominal) | €24.9 billion (2018)[1] |

| GDP per capita | €46,900 (2018)[2] |

| ISTAT | 021 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.888[3] very high |

| Website | www |

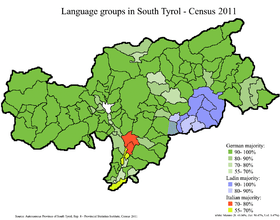

According to 2014 data based on the 2011 census, 62.3% of the population speaks German as first language (Standard German in the written form and an Austro-Bavarian dialect in the spoken form); 23.4% of the population speaks Italian, mainly in and around the two largest cities (Bolzano and Merano); 4.1% speaks Ladin, a Rhaeto-Romance language; 10.2% of the population (mainly recent immigrants) speaks another language natively.

The province is granted a considerable level of self-government, consisting of a large range of exclusive legislative and executive powers and a fiscal regime that allows it to retain 90% of revenue, while remaining a net contributor to the national budget.[5] As of 2016, South Tyrol is the wealthiest province in Italy and among the wealthiest in the European Union.

In the wider context of the European Union, the province is one of the three members of the Euroregion of Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino, which corresponds almost exactly to the historical region of Tyrol.[6] The other members are Tyrol state in Austria, to the north and east, and the Italian Autonomous province of Trento to the south.

Name

_The_Valleys_of_TIROL.jpg)

South Tyrol (occasionally South Tirol) is the term most commonly used in English for the province,[7] and its usage reflects that it was created from a portion of the southern part of the historic County of Tyrol, a former state of the Holy Roman Empire and crown land of the Austrian Empire of the Habsburgs. German and Ladin speakers usually refer to the area as Südtirol; the Italian equivalent Sudtirolo (sometimes parsed Sud Tirolo[8]) is becoming increasingly common.[9]

Alto Adige (literally translated in English: "Upper Adige"), one of the Italian names for the province, is also used in English.[10] The term had been the name of political subdivisions along the Adige River in the time of Napoleon Bonaparte,[11][12] who created the Department of Alto Adige, part of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy. It was reused as the Italian name of the current province after its post-World War I creation, and was a symbol of the subsequent forced Italianization of South Tyrol.[13]

The official name of the province today in German is Autonome Provinz Bozen — Südtirol. German speakers usually refer to it not as a Provinz, but as a Land (like the Länder of Germany and Austria).[14] Provincial institutions are referred to using the prefix Landes-, such as Landesregierung (state government) and Landeshauptmann (governor).[15] The official name in Italian is Provincia autonoma di Bolzano — Alto Adige, in Ladin Provinzia autonoma de Balsan/Bulsan — Südtirol.

History

Annexation by Italy

South Tyrol as an administrative entity originated during the First World War. The Allies promised the area to Italy in the Treaty of London of 1915 as an incentive to enter the war on their side. Until 1918 it was part of the Austro-Hungarian princely County of Tyrol, but this almost completely German-speaking territory was occupied by Italy at the end of the war in November 1918 and was annexed to the Kingdom of Italy in 1919. The province as it exists today was created in 1926 after an administrative reorganization of the Kingdom of Italy, and was incorporated together with the province of Trento into the newly created region of Venezia Tridentina ("Trentine Venetia").

With the rise of Italian Fascism, the new regime made efforts to bring forward the Italianization of South Tyrol. The German language was banished from public service, German teaching was officially forbidden, and German newspapers were censored (with the exception of the fascistic Alpenzeitung). The regime also favored immigration from other Italian regions.

The subsequent alliance between Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini declared that South Tyrol would not follow the destiny of Austria, which had been annexed to the Third Reich. Instead the dictators agreed that the German-speaking population be transferred to German-ruled territory or dispersed around Italy, but the outbreak of the Second World War prevented them from fully carrying out their intention. Every single citizen had the free choice to give up his German cultural identity and stay in fascist Italy, or to leave his homeland and move to Nazi Germany to retain this cultural identity. The result was that in these difficult times of fascism, the individual South Tyrolean families were divided and separated.

In 1943, when the Italian government signed an armistice with the Allies, the region was occupied by Germany, which reorganised it as the Operation Zone of the Alpine Foothills and put it under the administration of Gauleiter Franz Hofer. The region was de facto annexed to the German Reich (with the addition of the province of Belluno) until the end of the war. This status ended along with the Nazi regime, and Italian rule was restored in 1945.

Gruber-De Gasperi Agreement

After the war the Allies decided that the province would remain a part of Italy, under the condition that the German-speaking population be granted a significant level of self-government. Italy and Austria negotiated an agreement in 1946, recognizing the rights of the German minority. Alcide De Gasperi, Italy's prime minister, a native of Trentino, wanted to extend the autonomy to his fellow citizens. This led to the creation of the region called Trentino-Alto Adige/Tiroler Etschland. The Gruber-De Gasperi Agreement of September 1946 was signed by the Italian and Austrian Foreign Ministers, creating the autonomous region of Trentino-South Tyrol, consisting of the autonomous provinces of Trentino and South Tyrol. German and Italian were both made official languages, and German-language education was permitted once more. Still Italians were the majority in the combined region.

This, together with the arrival of new Italian-speaking immigrants, led to strong dissatisfaction among South Tyroleans, which culminated in terrorist acts perpetrated by the Befreiungsausschuss Südtirol (BAS — Committee for the Liberation of South Tyrol). In a first phase, only public edifices and fascist monuments were targeted. The second phase was bloodier, costing 21 lives (15 members of Italian security forces, two civilians, and four terrorists).

Südtirolfrage

The South Tyrolean question (Südtirolfrage) became an international issue. As the implementation of the post-war agreement was not seen as satisfactory by the Austrian government, it became a cause of significant friction with Italy and was taken up by the United Nations in 1960. A fresh round of negotiations took place in 1961 but proved unsuccessful, partly because of the campaign of terrorism.

The issue was resolved in 1971, when a new Austro-Italian treaty was signed and ratified. It stipulated that disputes in South Tyrol would be submitted for settlement to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, that the province would receive greater autonomy within Italy, and that Austria would not interfere in South Tyrol's internal affairs. The new agreement proved broadly satisfactory to the parties involved, and the separatist tensions soon eased.

The new autonomous status, granted from 1972 onwards, has resulted in a considerable level of self-government,[16] also due to the large financial resources of South Tyrol, retaining almost 90% of all levied taxes.[17]

Autonomy

In 1992, Italy and Austria officially ended their dispute over the autonomy issue on the basis of the agreement of 1972.[18]

The extensive self-government[16] provided by the current institutional framework has been advanced as a model for settling interethnic disputes and for the successful protection of linguistic minorities.[19] This is among the reasons why the Ladin municipalities of Cortina d'Ampezzo/Anpezo, Livinallongo del Col di Lana/Fodom and Colle Santa Lucia/Col have asked in a referendum to be detached from Veneto and reannexed to the province, from which they were separated under the fascist government.[20]

Euroregion

In 1996, the Euroregion Tyrol-South Tyrol-Trentino was formed between the Austrian state of Tyrol and the Italian provinces of South Tyrol and Trentino. The boundaries of the association correspond to the old County of Tyrol. The aim is to promote regional peace, understanding and cooperation in many areas. The region's assemblies meet together as one on various occasions, and have set up a common liaison office with the European Union in Brussels.

Geography

.png)

South Tyrol is located at the northernmost point in Italy. The province is bordered by Austria to the east and north, specifically by the Austrian federal-states Tyrol and Salzburg, and by the Swiss canton of Graubünden to the west. The Italian provinces of Belluno, Trentino, and Sondrio border to the southeast, south, and southwest, respectively.

The landscape itself is mostly cultivated with different types of shrubs and forests and is highly mountainous.

Entirely located in the Alps, the province's landscape is dominated by mountains. The highest peak is the Ortler (3,905 m) in the far west, which is also the highest peak in the Eastern Alps outside the Bernina Range. Even more famous are the craggy peaks of the Dolomites in the eastern part of the region.

The following mountain groups are (partially) in South Tyrol. All but the Sarntal Alps are on the border with Austria, Switzerland, or other Italian provinces. The ranges are clockwise from the west and for each the highest peak is given that is within the province or on its border.

| Name | Highest peak (German/Italian) | metres | feet |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ortler Alps | Ortler/Ortles | 3,905 | 12,811 |

| Sesvenna Range | Muntpitschen/Monpiccio | 3,162 | 10,374 |

| Ötztal Alps | Weißkugel/Palla Bianca | 3,746 | 12,291 |

| Stubai Alps | Wilder Freiger/Cima Libera | 3,426 | 11,241 |

| Sarntal Alps | Hirzer/Punta Cervina | 2,781 | 9,124 |

| Zillertal Alps | Hochfeiler/Gran Pilastro | 3,510 | 11,515 |

| Hohe Tauern | Dreiherrnspitze/Picco dei Tre Signori | 3,499 | 11,480 |

| Eastern Dolomites | Dreischusterspitze/Punta Tre Scarperi | 3,152 | 10,341 |

| Western Dolomites | Langkofel/Sassolungo | 3,181 | 10,436 |

Located between the mountains are many valleys, where the majority of the population lives.

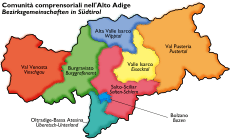

Administrative divisions

The province is divided into eight districts (German: Bezirksgemeinschaften, Italian: comunità comprensoriali), one of them being the chief city of Bolzano. Each district is headed by a president and two bodies called the district committee and the district council. The districts are responsible for resolving intermunicipal disputes and providing roads, schools, and social services such as retirement homes.

The province is further divided into 116 Gemeinden or comuni.[21]

Districts

| District (German/Italian) | Capital (German/Italian) | Area | Inhabitants[21] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bozen/Bolzano | Bozen/Bolzano | 52 km² | 107,436 |

| Burggrafenamt/Burgraviato | Meran/Merano | 1,101 km² | 97,315 |

| Pustertal/Val Pusteria | Bruneck/Brunico | 2,071 km² | 79,086 |

| Überetsch-Unterland/Oltradige-Bassa Atesina | Neumarkt/Egna | 424 km² | 71,435 |

| Eisacktal/Valle Isarco | Brixen/Bressanone | 624 km² | 49,840 |

| Salten-Schlern/Salto-Sciliar | Bozen/Bolzano | 1,037 km² | 48,020 |

| Vinschgau/Val Venosta | Schlanders/Silandro | 1,442 km² | 35,000 |

| Wipptal/Alta Valle Isarco | Sterzing/Vipiteno | 650 km² | 18,220 |

Largest municipalities

| German name | Italian name | Ladin name | Inhabitants[21] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bozen | Bolzano | Balsan, Bulsan | 107,724 |

| Meran | Merano | Maran | 40,926 |

| Brixen | Bressanone | Persenon, Porsenù | 22,423 |

| Leifers | Laives | 18,097 | |

| Bruneck | Brunico | Bornech, Burnech | 16,636 |

| Eppan an der Weinstraße | Appiano sulla Strada del Vino | 14,990 | |

| Lana | Lana | 12,468 | |

| Kaltern an der Weinstraße | Caldaro sulla Strada del Vino | 7,512 | |

| Ritten | Renon | 7,507 | |

| Sarntal | Sarentino | 6,863 | |

| Kastelruth | Castelrotto | Ciastel | 6,456 |

| Sterzing | Vipiteno | 6,306 | |

| Schlanders | Silandro | 6,014 | |

| Ahrntal | Valle Aurina | 5,876 | |

| Naturns | Naturno | 5,440 | |

| Sand in Taufers | Campo Tures | 5,230 | |

| Latsch | Laces | 5,145 | |

| Klausen | Chiusa | Tluses, Tlüses | 5,134 |

| Mals | Malles | 5,050 | |

| Neumarkt | Egna | 4,926 | |

| Algund | Lagundo | 4,782 | |

| St.Ulrich | Ortisei | Urtijëi | 4,606 |

| Ratschings | Racines | 4,331 | |

| Terlan | Terlano | 4,132 |

Climate

Climatically, South Tyrol may be divided into five distinct groups:

The Adige valley area, with cold winters (24-h averages in January of about 0 °C) and warm summers (24-h averages in July of about 23 °C), usually classified as Humid subtropical climate — Cfa. It has the driest and sunniest climate of the province. The main city in this area is Bolzano.

The midlands, between 300 and 900 metres, with cold winters (24-h averages in January between −3 °C and 1 °C) and mild summers (24-h averages in July between 15 °C and 21 °C); This is a typical Oceanic climate, classified as Cfb. It is usually wetter than the subtropical climate, and very snowy during the winters. During the spring and autumn, there is a large foggy season, but fog may occur even on summer mornings. Main towns in this area are Meran, Bruneck, Sterzing, and Brixen. Near the lakes in higher lands (between 1000 and 1400 meters) the humidity may make the climate in these regions milder during winter, but also cooler in summer, then, a Subpolar oceanic climate, Cfc, may occur.

The alpine valleys between 900 and 1400 metres, with a typically Humid continental climate — Dfb, covering the largest part of the province. The winters are usually very cold (24-h averages in January between −8 °C and −3 °C), and the summers, mild with averages between 14 and 19 °C. It is a very snowy climate; snow may occur from early October to April or even May. Main municipalities in this area are Urtijëi, Badia, Sexten, Toblach, Stilfs, Vöran, and Mühlwald.

The alpine valleys between 1400 and 1700 metres, with a Subarctic climate — Dfc, with harsh winters (24-h averages in January between −9 °C and −5 °C) and cool, short, rainy and foggy summers (24-h averages in July of about 12 °C). These areas usually have five months below the freezing point, and snow sometimes occurs even during the summer, in September. This climate is the wettest of the province, with large rainfalls during the summer, heavy snowfalls during spring and fall. The winter is usually a little drier, marked by freezing and dry weeks, although not sufficiently dry to be classified as a Dwc climate. Main municipalities in this area are Corvara, Sëlva, Santa Cristina Gherdëina.

The highlands above 1700 meters, with an alpine tundra climate, ET, which becomes an Ice Cap Climate, EF, above 3000 meters. The winters are cold, but sometimes not as cold as the higher valleys' winters. In January, most of the areas at 2000 meters have an average temperature of about −5 °C, while in the valleys at about 1600 meters, the mean temperature may be as low as −8 or −9 °C. The higher lands, above 3000 meters are usually extremely cold, with averages of about −14 °C during the coldest month, January.

Politics

.png)

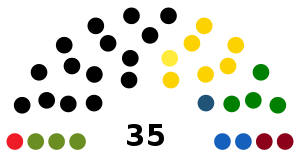

The local government system is based upon the provisions of the Italian Constitution and the Autonomy Statute of the Region Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol.[22] The 1972 second Statute of Autonomy for Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol devolved most legislative and executive competences from the regional level to the provincial level, creating de facto two separate regions.

The considerable legislative power of the province is vested in an assembly, the Landtag of South Tyrol (German: Südtiroler Landtag; Italian: Consiglio della Provincia Autonoma di Bolzano; Ladin: Cunsëi dla Provinzia Autonoma de Bulsan). The legislative powers of the assembly are defined by the second Statute of Autonomy.

The executive powers are attributed to the government (German: Landesregierung; Italian: Giunta Provinciale) headed by the Landeshauptmann Arno Kompatscher.[23] He belongs to the South Tyrolean People's Party, which has been governing with a parliamentary majority since 1948. South Tyrol is characterized by long sitting presidents, having only had two presidents between 1960 and 2014 (Silvius Magnago 1960–1989, Luis Durnwalder 1989–2014).

A fiscal regime allows the province to retain a large part of most levied taxes, in order to execute and administer its competences. Nevertheless, South Tyrol remains a net contributor to the Italian national budget.[24]

Last provincial elections

| ||||||

| Parties | Votes | % | Seats | +/− | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| South Tyrolean People's Party | 119,108 | 41.9 | 15 | −2 | ||

| Team Köllensperger | 43,315 | 15.2 | 6 | +6 | ||

| League | 31,510 | 11.1 | 4 | +4 | ||

| Greens | 19,391 | 6.8 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| Die Freiheitlichen | 17,620 | 6.2 | 2 | −4 | ||

| South Tyrolean Freedom | 16,927 | 6.0 | 2 | −1 | ||

| Democratic Party | 10,806 | 3.8 | 1 | −1 | ||

| Five Star Movement | 6,670 | 2.4 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Alto Adige in the Heart – Brothers of Italy | 4,883 | 1.7 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Citizens' Union | 3,664 | 1.3 | 0 | −1 | ||

| Us South Tyrol | 3,428 | 1.2 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Forza Alto Adige | 2,825 | 1.0 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| CasaPound Italy | 2,451 | 0.9 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| United Left | 1,753 | 0.6 | 0 | ±0 | ||

| Total | 284,351 | 100.0 | 35 | ±0 | ||

| Source: Province of Bolzano | ||||||

List of Governors

| Governors of South Tyrol | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

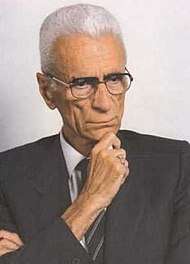

| Governor | Portrait | Party | Term | Legislature | |

|

SVP | 1948–1952 | I Legislature | ||

| 1952–1955 | II Legislature | ||||

|

SVP | 1955–1956 | |||

| 1956–1960 | III Legislature | ||||

|

SVP | 1960–1964 | IV Legislature | ||

| 1964–1968 | V Legislature | ||||

| 1968–1973 | VI Legislature | ||||

| 1973–1978 | VII Legislature | ||||

| 1978–1983 | VIII Legislature | ||||

| 1983–1988 | IX Legislature | ||||

| 1988–1989 | X Legislature | ||||

|

SVP | 1989–1993 | |||

| 1993–1998 | XI Legislature | ||||

| 1998–2003 | XII Legislature | ||||

| 2003–2008 | XIII Legislature | ||||

| 2008–2013 | XIV Legislature | ||||

| 2013–2014 | XV Legislature | ||||

|

SVP | 2014–2018 | |||

| 2018–present | XVI Legislature | ||||

Secessionist movement

Given the region's historical and cultural association with neighboring Austria, calls for the secession of South Tyrol and its reunification with Austria do surface from time to time among German- and Ladin-speakers, although falling short of an absolute majority in the province when considering also the Italian-speaking population, the majority does support a separation.[25] Among the political parties that support South Tyrol's reunification into Austria are South Tyrolean Freedom, Die Freiheitlichen and Citizens' Union for South Tyrol.[26]

Economy

In 2016 South Tyrol had a GDP per capita of €42,600, making it the richest province in Italy and one of the richest in the European Union.[27]

The unemployment level in 2007 was roughly 2.4% (2.0% for men and 3.0% for women). Residents are employed in a variety of sectors, from agriculture — the province is a large producer of apples, and its South Tyrol wine are also renowned — to industry to services, especially tourism. Spas located on the Italian Alps have become a favorite for tourists seeking wellness.[28]

South Tyrol is home to numerous mechanical engineering companies, some of which are the global market leaders in their sectors: the Leitner Group that specializes in cable cars and wind energy, TechnoAlpin AG, which is the global market leader in snow-making technology and the snow groomer company Prinoth.

Transport

The region is, together with northern and eastern Tyrol, an important transit point between southern Germany and Northern Italy. Freights by road and rail pass through here. One of the most important highways is the A22, also called the Autostrada del Brennero. It connects to the Brenner Autobahn in Austria.

The vehicle registration plate of South Tyrol is the two-letter provincial code Bz for the capital city, Bolzano. Along with the autonomous Trentino (Tn) and Aosta Valley (Ao), South Tyrol is allowed to surmount its license plates with its coat of arms.

Rail transport goes over the Brenner Pass. The Brenner Railway is a major line connecting the Austrian and Italian railways from Innsbruck and Verona climbing the Wipptal, passing over the Brenner Pass and descending down the Eisack Valley to Bolzano and then down the Adige Valley from Bolzano to Rovereto and to Verona. The line is part of the Line 1 of Trans-European Transport Networks (TEN-T).

Other railways are the Pustertalbahn, Ritten Railway and Vinschgaubahn. Due to the steep slopes of the mountains, a number of funiculars exist, such as the Gardena Ronda Express funicular and Mendel Funicular.

The Brenner Base Tunnel is under construction and scheduled to be completed by 2025. With a planned length of 55 km, this tunnel will increase freight train average speed to 120 km/h and reduce transit time by over an hour.[29]

Larger cities used to have their own tramway system, such as the Meran Tramway and Bolzano Tramway. These were replaced after the Second World War with buses. Many other cities and municipalities have their own bus system or are connected with each other by it.

The Bolzano Airport is the only airport serving the region.

Demographics

Languages

- Further information: Linguistic and demographic history of South Tyrol

| Languages of South Tyrol. Majorities per municipality in 2011: | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | |

| Source | astat info 6/2012, 38, Volkszählung 2011/Censimento della popolazione 2011, p. 6-7 |

German and Italian are both official languages of South Tyrol. In some eastern municipalities Ladin is the third official language. A majority of the inhabitants of contemporary South Tyrol speak native Austro-Bavarian dialects of the German language. Standard German plays a dominant role in education and media.

Every citizen has the right to use their own mother tongue, even at court. Schools are separated for each language group.

All traffic signs are officially bi- or trilingual. Most Italian toponyms are translations performed by Italian nationalist Ettore Tolomei, the author of the Prontuario dei nomi locali dell'Alto Adige.[30]

In order to reach a fair allocation of jobs in public service a system called ethnic proportion (Italian: proporzionale etnica, German: ethnischer Proporz) has been established. Every ten years, when the general census of population takes place, each citizen has to declare to which linguistic group they belong or want to be aggregated to. According to the results they decide how many people of which group are going to be employed in public service.

At the time of the annexation of the southern part of Tyrol by Italy in 1919, the overwhelming majority of the population spoke German and identified with the Austrian or German nationality: In 1910, according to the last population census before World War I, the German-speaking population numbered 224,000, the Ladin 9,000 and the Italian 7,000.[31] As a result of the Italianization of South Tyrol about 23% of the population are Italian-speakers (they were 33%, 138,000 of 414,000 inhabitants in the 1971 census) according to the census of 2011. 103 out of 116 comuni have a majority of German native speakers — with Martell reaching 100% — eight have a Ladin-speaking majority, and five a majority of Italian speakers. The Italian-speaking population lives mainly around the provincial capital Bolzano, where they are the majority (73.8% of the inhabitants), and partially a result of Benito Mussolini's policy of Italianisation after he took power in 1922, when he encouraged immigration from the rest of Italy.[32] The other four comuni where the Italian-speaking population is the majority are Laives, Salorno, Bronzolo and Vadena. The eight comuni with Ladin majorities are: La Val, Badia, Corvara, Mareo, San Martin de Tor, Santa Cristina Gherdëina, Sëlva, Urtijëi.

The linguistic breakdown according to ASTAT 2014 (based on the census of 2011):[33]

| Language | Number | % |

|---|---|---|

| German | 314,604 | 62.3% |

| Italian | 118,120 | 23.4% |

| Ladin | 20,548 | 4.1% |

| Other | 51,371 | 10.2% |

| Total | 504,643 | 100% |

Religion

South Tyrol is predominantly Roman Catholic: 96.1% of resident population in the area of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Bolzano-Brixen (its territory corresponds with that of the province of South Tyrol) in 2015.[34] There is a Lutheran community in Merano (founded 1861) and another one in Bolzano (founded 1889). Since the Middle Ages the Jewish presence has been documented in South Tyrol. In 1901 the Synagogue of Merano was built. As of 2015, South Tyrol was home to about 14,000 Muslims.[35]

Culture

Education

Architecture

The region features a large number of castles and churches. Many of the castles and Ansitze were built by the local nobility and the Habsburg rulers. See List of castles in South Tyrol.

Museums

Among the major museums of South Tyrol are:

- the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology, which has the mummy of Ötzi the Iceman

- the Museion, Museum of modern and contemporary art of Bolzano

- the Messner Mountain Museum of Reinhold Messner

Media

German-language TV channels in South Tyrol:

Music

The Bozner Bergsteigerlied and the Andreas-Hofer-Lied are considered to be the unofficial anthems of South Tyrol.[36]

The folk musical group Kastelruther Spatzen from Kastelruth and the rock band Frei.Wild from Brixen have received high recognition in the German-speaking part of the world.

Award-winning electronic music producer Giorgio Moroder was born and raised in South Tyrol in a mixed Italian, German and Ladin-speaking environment.

Sports

South Tyroleans have been successful at winter sports and they regularly form a large part of Italy's contingent at the Winter Olympics. Famed mountain climber Reinhold Messner, the first climber to climb Mount Everest without the use of oxygen tanks, was born and raised in the region. Other successful South Tyroleans include luger Armin Zöggeler, figure skater Carolina Kostner, skier Isolde Kostner, luge and bobsleigh medallist Gerda Weissensteiner and tennis player Andreas Seppi. HC Interspar Bolzano-Bozen Foxes are one of Italy's most successful ice hockey teams, while the most important football club in South Tyrol is F.C. Südtirol, which is currently (2018) playing in Serie C (third highest league in Italy).

The province is famous worldwide for its mountain climbing opportunities, while in winter it is home to a number of popular ski resorts including Val Gardena, Alta Badia and Alpe di Siusi.

References

- "Eurostat – Tables, Graphs and Maps Interface (TGM) table". European Commission. 12 August 2011. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 31% to 626% of the EU average in 2017" (Press release). ec. europa.eu. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi. globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Statuto speciale per il Trentino-Alto Adige .

- Provincia Autonmia di Alto Adige, official site)

- Cortina d'Ampezzo, Livinallongo/Buchenstein and Colle Santa Lucia, formerly parts of Tyrol, now belong to the region of Veneto.

- Cf. for instance Antony E. Alcock, The History of the South Tyrol Question, London: Michael Joseph, 1970; Rolf Steininger, South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, 2003.

- Bondi, Sandro (25 January 2011), Lettera del ministro per i beni culturali Bondi al presidente del consiglio Durnwalder (Letter) (in Italian), Rome: Il Ministro per i Beni e le Attività Culturali, retrieved 4 June 2011

- Cole, John (2003), "The Last Become First: The Rise of Ultimogeniture in Contemporary South Tyrol", in Grandits, Hannes; Heady, Patrick (eds.), Distinct Inheritances: Property, Family and Community in a Changing Europe, Münster: Lit Verlag, p. 263, ISBN 3-8258-6961-X

- Cfr. for instance this article from britishcouncil.org

- Cisalpine Republic (1798). Raccolta delle leggi, proclami, ordini ed avvisi, Vol 5 (in Italian). Milan: Luigi Viladini. p. 184.

- Frederick C. Schneid (2002). Napoleon's Italian campaigns 1805–1815. Milan: Praeger Publishers. p. 99. ISBN 9780275968755.

- Steininger, Rolf (2003), South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, p. 21, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- Heiss, Hans (2003), "Von der Provinz zum Land. Südtirols Zweite Autonomie", in Solderer, Gottfried (ed.), Das 20. Jahrhundert in Südtirol. 1980 – 2000, V, Bozen/Bolzano: Raetia, p. 50, ISBN 978-88-7283-204-2

- Website of the Province

- Danspeckgruber, Wolfgang F. (2002). The Self-Determination of Peoples: Community, Nation, and State in an Interdependent World. Lynne Rienner Publishers. p. 193. ISBN 1555877931.

- Anthony Alcock. "The South Tyrol Autonomy. A Short Introduction" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Rolf Steininger: "South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century", Transaction Publishers, 2003, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4, pp.2

- "Tbilisi's S.Ossetia Diplomatic Offensive Gains Momentum". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- "Referendum Cortina, trionfo dei "sì" superato il quorum nei tre Comuni". La Repubblica. Rome. 29 October 2007. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- "South Tyrol in figures" (PDF). Provincial Statistics Institute (ASTAT). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- "Special Statute for Trentino-Alto Adige" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- Mayr, Walter (25 August 2010). "The South Tyrol Success Story: Italy's German-Speaking Province Escapes the Crisis". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Durnwalder's party, the South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP), ...has ruled the province with an absolute or relative majority since 1948.

- "Dati Regionali 2012 shock: Residuo Fiscale (saldo attivo per 95 miliardi al Nord)". 27 May 2013. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- "South Tyrol heading to unofficial independence referendum in autumn". 7 March 2013. Nationalia.info. Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- "Website of South Tylorean Freedom". Retrieved 28 March 2014.

- Regional GDP in the European Union, 2016

- Rysman, Laura (4 February 2019). "Italian Alpine Spas, Where Sports Are an Afterthought". NYT.

- "The Brenner Base Tunnel". Brenner Basistunnel BBT SE. Archived from the original on 2 February 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2014.

- Steininger, Rolf (2003), South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century, New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers, pp. 21–46, ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- Oscar Benvenuto (ed.): "South Tyrol in Figures 2008", Provincial Statistics Institute of the Autonomous Province of South Tyrol, Bozen/Bolzano 2007, p. 19, Table 11

- Steininger, Rolf (2003). South Tyrol, A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-7658-0800-5.

- "Statistisches Jahrbuch für Südtirol 2014 / Annuario statistico della Provincia di Bolzano 2014" (PDF). Table 3.18, page 118. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Catholic Hierarchy. Archdiocese Bolzano-Brixen, table "statistics"

- Parteli, Elisabeth (15 January 2015). "Verdächtig religiös (German)". ff – Südtiroler Wochenmagazin, Nr. 4. pp. 36–47. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Rainer Seberich (1979). "Singen unter dem Faschismus: Ein Untersuchungsbericht zur politischen und kulturellen Bedeutung der Volksliedpflege". Der Schlern, 50,4, 1976, pp. 209–218, here p. 212.

Bibliography

- (in German) Gottfried Solderer (ed) (1999–2004). Das 20. Jahrhundert in Südtirol. 6 Vol., Bozen: Raetia Verlag. ISBN 978-88-7283-137-3

- Antony E. Alcock (2003). The History of the South Tyrol Question. London: Michael Joseph. 535 pp.

- Rolf Steininger (2003). South Tyrol: A Minority Conflict of the Twentieth Century. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7658-0800-4

- Georg Grote (2012). The South Tyrol Question 1866–2010. From National Rage to Regional State. Oxford: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-336-1

- Georg Grote, Hannes Obermair (2017). A Land on the Threshold. South Tyrolean Transformations, 1915–2015. Oxford/Bern/New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-0343-2240-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to South Tyrol. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for South Tyrol. |

- Official website for the Civic Network of South Tyrol, the Autonomous Province of Bolzano/Bozen

- Special Statute for Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol

- Tourist information about South Tyrol

- The most accurate digital map of South Tyrol

.jpg)