Fuchsine

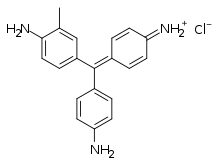

Fuchsine (sometimes spelled fuchsin) or rosaniline hydrochloride is a magenta dye with chemical formula C20H19N3·HCl.[1][2] There are other similar chemical formulations of products sold as fuchsine, and several dozen other synonyms of this molecule.[1]

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-[(4-Aminophenyl)-(4-imino-1-cyclohexa-2,5-dienylidene)methyl]aniline hydrochloride | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) |

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.010.173 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID |

|||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C20H19N3·HCl | |||

| Molar mass | 337.86 g/mol (hydrochloride) | ||

| Appearance | Dark green powder | ||

| Melting point | 200 °C (392 °F; 473 K) | ||

| 2650 mg/L (25 °C (77 °F)) | |||

| log P | 2.920 | ||

| Vapor pressure | 7.49×10−10 mmHg (25 °C) | ||

Henry's law constant (kH) |

2.28×10−15 atm⋅m3/mole (25 °C) | ||

Atmospheric OH rate constant |

4.75×10−10 cm3/molecule⋅sec (25 °C) | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Main hazards | Ingestion, inhalation, skin and eye contact, combustible at high temperature, slightly explosive around open flames and sparks. | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

| Infobox references | |||

It becomes magenta when dissolved in water; as a solid, it forms dark green crystals. As well as dying textiles, fuchsine is used to stain bacteria and sometimes as a disinfectant. In the literature of biological stains the name of this dye is frequently misspelled, with omission of the terminal -e, which indicates an amine.[3] American and English dictionaries (Webster's, Oxford, Chambers, etc.) give the correct spelling, which is also used in the literature of industrial dyeing.[4] It is well established that production of fuchsine results in development of bladder cancers by production workers. Production of magenta is listed as a circumstance known to result in cancer.[5]

History

Fuchsine was first prepared by August Wilhelm von Hofmann from aniline and carbon tetrachloride in 1858.[6][7] François-Emmanuel Verguin discovered the substance independently of Hofmann the same year and patented it.[8] Fuchsine was named by its original manufacturer Renard frères et Franc,[9] is usually cited with one of two etymologies: from the color of the flowers of the plant genus Fuchsia,[10] named in honor of botanist Leonhart Fuchs, or as the German translation Fuchs of the French name Renard, which means fox.[11] An 1861 article in Répertoire de Pharmacie said that the name was chosen for both reasons.[12][13]

Acid fuchsine

Acid fuchsine is a mixture of homologues of basic fuchsine, modified by addition of sulfonic groups. While this yields twelve possible isomers, all of them are satisfactory despite slight differences in their properties.

Basic fuchsine

Basic fuchsine is a mixture of rosaniline, pararosaniline, new fuchsine and Magenta II.[14] Formulations usable for making of Schiff reagent must have high content of pararosanilin. The actual composition of basic fuchsine tends to somewhat vary by vendor and batch, making the batches differently suitable for different purposes.

In solution with phenol (also called carbolic acid) as an accentuator[15] it is called carbol fuchsin and is used for the Ziehl–Neelsen and other similar acid-fast staining of the mycobacteria which cause tuberculosis, leprosy etc.[16] Basic fuchsine is widely used in biology to stain the nucleus, and is also a component of Lactofuchsin, used for Lactofuchsin mounting.

Properties

The crystals pictured at the right are of basic fuchsine, also known as basic violet 14, basic red 9, pararosanaline or CI 42500. Their structure differs from the structure shown above by the absence of the methyl group on the upper ring, otherwise they are quite similar.

They are soft, with a hardness of less than 1, about the same as or less than talc. They possess a strong metallic lustre and a green yellow color. They leave dark greenish streaks on paper and when these are moistened with a solvent, the strong magenta colour appears.

Chemical structure

Fuchsine is an amine salt and has three amine groups, two primary amines and a secondary amine. If one of these is protonated to form ABCNH+, the positive charge is delocalized across the whole symmetrical molecule due to pi cloud electron movement.

The positive charge can be thought of as residing on the central carbon atom and all three "wings" becoming identical aromatic rings terminated by a primary amine group. Other resonance structures can be conceived, where the positive charge "moves" from one amine group to the next, or one third of the positive charge resides on each amine group. The ability of fuchsine to be protonated by a stronger acid gives it its basic property. The positive charge is neutralized by the negative charge on the chloride ion. The positive "basic fuchsinium ions" and negative chloride ions stack to form the salt "crystals" depicted above.

See also

- New fuchsine and Acid fuchsine are related dyes

- Fuchsine is a component in the Schiff test

- Fuchsine is now often used in the Gram stain procedure in microbiology.

- Basic Fuchsine is a component in the Lactofuchsin mount

References

- "Basic chemical data". Discovery Series online database, Developmental Therapeutics Program, U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved on 2007-10-08.

- Goyal, S.K. "Use of rosaniline hydrochloride dye for atmospheric SO2 determination and method sensitivity analysis". Journal of Environmental Monitoring, 3, 666–670, doi:10.1039/b106209n. Retrieved on 2007-10-08.

- Baker JR (1958) Principles of Biological Microtechnique. London: Methuen.

- Hunger K (2003) Industrial Dyes. Chemistry, Properties, Applications. Weinheim: wiley-VHC.

- Participants Lyon, 5–12 February 2008 (2010). "MAGENTA AND MAGENTA PRODUCTION" (PDF). IARC MONOGRAPHS ON THE EVALUATION OF CARCINOGENIC RISKS TO HUMANS. 99. International Agency for Research on Cancer, World Health Organization: 297 to 324. Retrieved January 12, 2013.

Magenta production is carcinogenic to humans (Group 1).

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - von Hofmann, August Wilhelm (1859). "Einwirkung des Chlorkohlenstoffs auf Anilin. Cyantriphenyldiamin". Journal für Praktische Chemie. 77: 190. doi:10.1002/prac.18590770130.

- von Hofmann, August Wilhelm (1858). "Action of Bichloride of Carbon on Aniline". Philosophical Magazine: 131–142.

- Dr Quesneville (1865). Le Moniteur Scientifique : Journal des Sciences pures et appliquees [The Scientific Monitor: Journal of Pure and Applied Sciences] (in French). Paris, France. pp. 42–46.

- Béchamp, M. A. (January–June 1860.) "Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des sciences. 1860. (T. 50)." French Academy of Sciences, Mallet-Bachelier: Paris, tome 50, page 861. Retrieved on 2007-09-25.

- (2004.) "Fuchsin" The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, Houghton Mifflin Company, via dictionary.com. Retrieved on 2007-09-20

- "Fuchsine." Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine (Website.) ARTFL Project: 1913 Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary. Retrieved on 2007-09-25

- Chevreul, M. E. (July 1860). "Note sur les étoffes de soie teintes avec la fuchsine, et réflexions sur le commerce des étoffes de couleur." Répertoire de Pharmacie, tome XVII, p. 62. Retrieved on 2007-09-25.

- Belt, H. V. D.; Hornix, Willem J.; Bud, Robert; Van Den Belt, Henk (1992). "Why Monopoly Failed: The Rise and Fall of Société La Fuchsine". The British Journal for the History of Science. 25 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1017/S0007087400045325. JSTOR 4027004.

- Horobin RW & Kiernan JA 20002. Conn's Biological Stains, 10th ed. Oxford: BIOS, p. 184–191

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2012-06-28.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Clark G 1973 Staining Procedures Used by the Biological Stain Commission, 3rd ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, pp. 252–254