Romanian Campaign (1916)

After a series of quick tactical victories on the numerically overpowered Austro-Hungarian forces in Transylvania, in the autumn of 1916, the Romanian Army suffered a series of devastating defeats, which forced the Romanian military and administration to withdraw to Western Moldavia, allowing the Central Powers to occupy two thirds of the national territory, including the state capital, Bucharest.

| The Participation of Romania in the Campaign of 1916 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Romanian Campaign of World War I | |||||||

Falkenhayn's cavalry entering Bucharest on 6 December 1916 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

1916:[1]:p. 254 1917:[3] |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

The main causes of the Romanian Army’s defeat by the numerically inferior German and Austro-Hungarian forces in the campaign of 1916 were the major political interferences in the act of military supervision, the incompetence, the imposture and the cowardice of a significant part of the military echelon of conduct, as well as the lack of an adequate training and troops’ equipment for that specific type of war.

The offensive in Transylvania

In the night of 27 August 1916, three Romanian armies started the attack by crossing the Southern Carpathians and entering Transylvania. The first attacks were paved with success, forcing the Austro-Hungarians to retreat. While the Romanian army was advancing in Transylvania at 9 p.m., the Romanian ambassador in Vienna, count Edgar Mavrocordat, presented Romania’s declaration of war at the secretariat of the Austria-Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. During that day, many Romanians with Austria-Hungarian citizenship were arrested in Bucharest. Among these were Ioan Slavici and Ioan Bălan.

By mid-September the Germans transferred four divisions on the front of Transylvania and stopped the Romanian advance. The Russians moved three divisions in order to help Romanians, but these troops were not equipped properly.

General Esposito affirmed that the Romanian army leaders made some strategic and operational mistakes:

From a military point of view, the Romanian strategy had been the worst. By choosing Transylvania as a primary objective, the Romanian army totally ignored the Bulgarian army behind it. When the offensive through the mountains failed, the High Romanian Commandment refused to save the forces on the front in order to allow the creation of a moving supply, with which the later threat of Falkenhayn would rejected. Romanians never amassed its forces appropriate in order to obtain the concentration of the fight power.[6]

Battle of Turtucaia

The first counterattack of the Central Powers was organized by General August von Mackensen, who coordinated a multinational army consisting of Bulgarian, German and Turkish troops. The northward attack was initiated by Bulgaria on 1 September. The attack was directed from the positions on the Danube to Constanța. Bulgarian troops, including the German-Bulgarian Detachment,[7] surrounded and stormed the fortress of Turtucaia. The Battle of Turtucaia ended with the capitulation of the Romanian garrison on September 6. Simultaneously with the assault, the Bulgarian Third Army with the 75th Turkish regiment[8], defeated a Romanian-Russian force including the First Serbian Volunteer Division at the Battle of Bazargic, despite the almost double superiority of the Entente.[9]

Flămânda Offensive

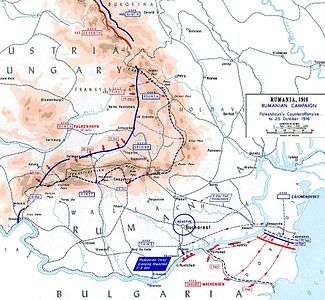

On 15 September, the Romanian Council of War decided to suspend the offensive in Transylvania and to concentrate instead on the destruction of the Mackensen groups of armies. The plan, known as Flămânda Offensive, consisted in an attack on the Central Powers forces through a flank and back shot, after the crossing of Danube at Flămânda, while, on the main front line, the Romanian-Russian troops had to launch an offensive from Cobadin towards Kurtbunar. On 1 October, two Romanian divisions forced the course of the Danube at Flămânda and created a large bridgehead of 14 kilometers and 4 kilometers in depth. On the same day, the Romanian-Russian division initiated an offensive on the frontline of Dobruja which recorded limited success. The failed attempt to break the German-Bulgarian front in Dobruja, combined with the violent storm during the night of October 1/October 2, which damaged the pontoon bridge over Danube, determined Averescu to cancel the whole operation. The consequences of this failure were big for the rest of the campaign.

The defense of the passes

The command of the Austrian-Hungarian troops in Transylvania was assigned to Erich von Falkenhayn, who was fired from the position of Chief of General Staff after the failure at the Battle of Verdun, the opening of the Allied offensive on the Somme, the Brusilov Offensive and the entry of Romania into the war. He initiated his own offensive on 1 September. The first attack was directed against the Romanian 1st Army near the city of Hațeg. The attack stopped the advance of the Romanians. After eight days, two divisions of German mountain infantry almost managed to disperse the Romanian marching columns near Sibiu. The Romanian troops had to retreat towards the mountains, and the Germans managed to occupy Turnu Roșu Pass. On 4 October, the Romanian 2nd Army attacked the German forces at Brașov, but it was repulsed. The 4th Army that operated in the north of the country retreated when the 1st Austro-Hungarian Army exerted a moderate pressure on it. Therefore, by 25 October, the Romanian Army retreated to the initial lines before the offensive.

"Deutsches Alpenkorps

26.-29.9.1916"

The forces under the command of Falkenhayn executed a certain number of attack tests in the passes of Carpathians in order to test the weak points of the defense. On 10 November, after a few weeks of concentration of their best troops, the elite unit Alpenkorps, Germans attacked in front of the Vulcan Pass, so that they pushed back the Romanian defenders into the mountains. On 26 November, fighting took to the hills. In the mountains, the snowfall started and soon the military operations stopped. The German 9th Army advanced in other sectors of the battle front, attacking all of the passes of the Southern Carpathians, Romanians being forced to retreat constantly, whenever their lines of supply became more and more stretched.

The retreat

The operations in Dobruja

On 1 September 1916, the Bulgarian 3rd Army passed the Bulgarian-Romanian border and advanced into Dobruja.

The Russian General Andrei Mederdovici Zaioncikovski together with its troops arrived immediately in order to strengthen the allied Romanian-Russian front in an attempt to stop the army of Mackensen before it would conquer the Bucharest–Constanța railway. Heavy fighting followed with intense attacks and counterattacks until 21 September.

In Dobruja, General Mackensen launched a new offensive on 19 October. After a month of cautious preparations, the mixed troops under his command managed to defeat the Romanian and Russian troops. The Allies were forced to retreat from Constanța to the Danube Delta. The Russian Army was not only demoralized, but also left without supplies. Mackensen chose to transfer secretly half of his army near Svishtov, preparing to cross the Danube in force.

The defense of Bucharest

On 23 November, the best trained troops under the command of Mackensen crossed the Danube, leaving from two locations near Svishtov. The German attack took the Romanians by surprise, the front getting closer to Bucharest. The attack of Mackensen threatened to cut in two the Romanian front, and the new Chief of General Staff, the newly promoted General Constantin Prezan, tried to organize a desperate counterattack. The plan was very audacious since it used the entire reserve of the Romanian Army. Yet it needed the cooperation of the Russians for success in order to stop the offensive of Mackensen, while the Romanian Army would have had to attack exactly at the junction between Mackensen's and Falkenhayn's forces. The Russian Army did not agree with the plan and refused to cooperate.

On 1 December, the Romanian army attacked anyway. Mackensen managed to transfer forces to Falkenhayn’s front of attack. After the containment of the Romanian offensive, Germans counterattacked at every point possible.

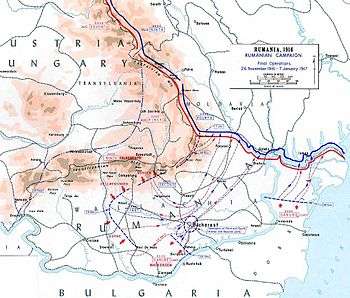

The stabilisation of the battlefront in Moldavia

The Government and the Romanian royal court retreated to Iași. On 6 December, Bucharest was occupied by the German cavalry. Only the bad weather and roads saved a good part of the Romanian Army from surrounding or destruction. Nevertheless, over 150,000 Romanian soldiers had been captured.

Russians were forced to send massive re-enforcements on the Romanian front to avoid a German invasion into the south of Russia. After many low-intensity engagements, the German Army stopped their advance by mid January 1917. The Romanian Army continued to fight, although the most part of its territory was under foreign occupation.

The losses of the Romanian army were estimated at 300–400,000 soldiers, dead, wounded, missing or prisoners.[10] The cumulated losses of the Germans, Austrians, Bulgarians, and Turks were estimated to approximately 60,000 individuals.

The victorious campaign strengthened very much the morale of the German troops and its generals Falkenhayn and Mackensen.[6] In many cases, the victories were attained by German divisions, with Bulgarian assistance in the south. Germans proved themselves superior at every chapter: supplying, equipment, training and the capacity of the leaders. Among the young officers from the elite troops Alpenkorps who fought on the Romanian front was the future Field Marshal Erwin Rommel.

Footnotes

- William C. King, King's Complete History of the World War: 1914-1918, History Associates, Springfield, Massachusetts, 1922

- (in Romanian) România în războiul mondial 1916-1919, Documente, Anexe, Volumul 1, Monitorul Oficial și Imprimeriile Statului, București, 1934, p. 58 Cifrele efectivelor militare mobilizate de România prezintă mici deosebiri în diferitele lucrări de referință.

- The Romanian Front - 1917, access date 12 August 2014

- (in Bulgarian) Министерство на войната, Щаб на войската, Българската армия в Световната война 1915 - 1918, Vol. VIII, Държавна печатница, Sofia, 1939

- WWI Casualty and Death Tables, access date la 12 august 2014

- Esposito, Atlas of American Wars, vol 2

- Glenn E. Torrey,"The Battle of Turtucaia (Tutrakan) (2–6 September 1916): Romania's Grief, Bulgaria's Glory"

- General Stefan Toshev 1921 “The activity of the 3rd Army in Dobrudja in 1916”, p.68; Действията на III армия в Добруджа 1916, стр. 68

- Симеонов, Радослав, Величка Михайлова и Донка Василева. Добричката епопея. Историко-библиографски справочник, Добрич 2006

- (in Romanian) istorie-edu.ro

Further reading

- (in Romanian) Abrudeanu, Ion Rusu, România si războiul mondial: contributiuni la studiul istoriei războiului nostru, Editura SOCEC & Co., București, 1921

- (in Romanian) Ardeleanu, Eftimie; Oșca, Alexandru; Preda Dumitru, Istoria Statului Major General Român, Editura Militară, București, 1994

- (in Romanian) Averescu, Alexandru, Notițe zilnice din războiu (1916-1918), Editura Grai și Suflet - Cultura Națională, București

- (in Romanian) Bărbulescu, Mihai; Deletant, Dennis; Hitchins, Keith; Papacostea, Șerban; Teodor, Pompiliu, Istoria României, Editura Enciclopedică, București, 1998

- (in Romanian) Buzatu, Gheorghe; Dobrinescu, Valeriu Florin; Dumitrescu, Horia, România și primul război mondial, Editura Empro, București, 1998

- (in Romanian) Chiriță, Mihai; Moșneagu, Marian; Florea, Petrișor; Duță, Cornel, Statul Major General în arhitectura organismului militar românesc: 1859-2009, Editura Centrului Tehnic-Editorial al Armatei, București, 2009

- (in Romanian) Ciobanu, Nicolae; Zodian, Vladimir; Mara, Dorin; Șperlea, Florin; Mâță, Cezar; Zodian, Ecaterina, Enciclopedia Primului Război Mondial, Editura Teora, București, f.a.

- (in Romanian) Falkenhayn, Erich von, Campania Armatei a 9-a împotriva românilor și a rușilor, Atelierele Grafice Socec & Co S.A., București, 1937

- (in Romanian) Hitchins, Keith, România 1866-1947, Editura Humanitas, București, 2013

- (in Romanian) Kirițescu, Constantin, Istoria războiului pentru întregirea României, Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică, București, 1989

- (in Romanian) Oroian, Teofil; Nicolescu Gheorghe; Dumitrescu, Valeriu-Florin; Oșca Alexandru; Nicolescu, Andrei, Șefii Statului Major General Român (1859 – 2000), Fundația „General Ștefan Gușă”, Editura Europa Nova, București, 2001

- (in Romanian) Scurtu, Ioan; Alexandrescu, Ion; Bulei, Ion; Mamina, Ion, Enciclopedia de istorie a Romaniei, Editura Meronia, Bucuresti, 2001

- ***(in Romanian), România în războiul mondial 1916-1919, Documente, Anexe, Volumul 1, Monitorul Oficial și Imprimeriile Statului, București, 1934

- ***(in Romanian), Marele Cartier General al Armatei României. Documente 1916 – 1920, Editura Machiavelli, București, 1996

- ***(in Romanian), Istoria militară a poporului român, vol. V, Editura Militară, București, 1989

- ***(in Romanian), România în anii primului Război Mondial, Editura Militară, București, 1987

- ***(in Romanian), România în primul război mondial, Editura Militară, 1979