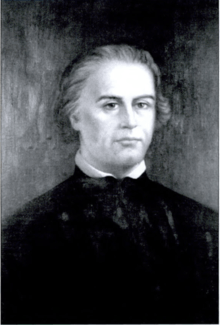

Robert Plunkett

Robert Plunkett (1752 – January 15, 1815) was an English Catholic priest and Jesuit missionary to the United States who became the first president of Georgetown College. Born in England, he was educated at the Colleges of St Omer and Bruges, as well as at the English College at Douai. There, he entered the Society of Jesus in 1769, but left four years later, just before learning of the papal order suppressing the Society. Therefore, he was ordained a secular priest at the English College, and became the chaplain to a monastery of English Benedictine nuns in exile in Brussels.

Robert Plunkett | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st President of Georgetown College | |

| In office 1791–1793 | |

| Succeeded by | Robert Molyneux |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1752 England |

| Died | January 15, 1815 (aged 62–63) St. Mary's County, Maryland, United States |

| Resting place | Georgetown Visitation Monastery |

| Alma mater | |

Plunkett petitioned to be sent to the United States as a missionary in 1789. Shortly after his arrival in 1790, Bishop John Carroll persuaded him to become the president of the newly established Georgetown College. Plunkett oversaw construction of the college's first building, the appointment of the first professor, and admission of the first student, William Gaston. However, he was more interested in pastoral work than education, and resigned the office two years later. Plunkett spent the remainder of his life ministering in rural Maryland, though continued to remain involved in the college's affairs.

Early life

Robert Plunkett was born in 1752,[1] in England.[2] He was educated at the Colleges of St Omer and Bruges from 1763 to 1768,[3] before attending the English College at Douai. He entered the Society of Jesus in 1769, but left the order on August 21, 1773, after the promulgation of a papal brief suppressing the Jesuits worldwide, but before news of this brief reached him in the Low Countries. Therefore, he continued his studies at Douai as a secular seminarian, and was ordained a priest there.[4] After his ordination, Plunkett became the chaplain to the Monastery of Our Lady of the Assumption in Brussels, in the Austrian Netherlands,[5] which housed a community of Benedictine nuns who had been exiled from England.[6]

On April 20, 1789, Plunkett formally requested permission from the Vicar Apostolic of the London District to go to the United States as a missionary. As a result of the Jesuits' fourth vow concerning missionary work, the permission of the Holy See was required as well, and Plunkett's request was forwarded to the Sacred Congregation de Propaganda Fide. The prefect of the congregation, Cardinal Leonardo Antonelli, approved the request and informed John Carroll, the Prefect Apostolic of the United States, who had been recruiting Jesuits in Europe to run the newly established Georgetown College in Maryland.[5]

On May 1, 1790,[7] Plunkett set sail for America from Texel, aboard a ship called The Brothers,[8] along with Charles Neale, a group of four Discalced Carmelite sisters from Hoogstraten who were going to found a convent in the United States.[9] The cost of his voyage, £50 (equivalent to £6,000 in 2019[10]), was defrayed by the Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland.[11][lower-alpha 1] The journey was prolonged because the captain had taken aboard goods to be delivered to Santa Cruz de Tenerife in the Canary Islands.[8] Plunkett frequently went ashore while the ship was in port in Santa Cruz.[13] He laid to rest the concerns of the local ecclesiastical authorities, who learned of a rumor that the Carmelite sisters were nuns fleeing their monastery with the aid of the two priests.[14][lower-alpha 2] The vessel arrived in New York City on July 2, 1790. Plunkett then departed Neale and the Carmelites and continued his journey to Maryland by land.[15] His first assignment was at the Jesuit plantation in White Marsh, Maryland.[1]

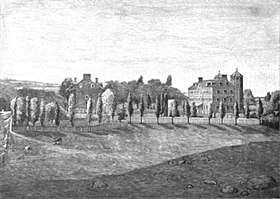

Georgetown College

Though Bishop Carroll was aware Plunkett had traveled to the United States seeking of pastoral, rather than educational work, he persuaded the reluctant Plunkett to become the first president of Georgetown College. Carroll concluded that the few other former Jesuits in the United States either could not be removed from important ministries or were not suited to teaching.[1] He had initially sought to name a distinguished English ex-Jesuit as the head of the college, such as Charles Plowden or Robert Molyneux, but they were unwilling to assume the position.[16]

Construction of the college was nearly completed in late 1791.[16] A French Sulpician seminarian, Jean-Edouard de Mondésir, became the first professor at the college in October of that year, while still learning English from Plunkett.[17] As funds for the school were meager, Carroll preferred seminarians or Jesuit scholastics over full-time professors, as he was able to pay them only 75 Maryland pounds plus room and board, substantially below the average £150-200 salary for professors in the country.[17]

The first student, William Gaston, arrived at Georgetown from New Bern, North Carolina in early 1791, to find the college not yet open. He returned again in November, and lived at the City Tavern, as the college building was not complete. Eventually, Gaston began classes on January 2, 1792, along with Charles Philemon Wederstrandt, from the Eastern Shore of Maryland. During Plunkett's term, the number of students rose steadily, totaling 40 by July 1792, and hailing from as far away as New York City and the West Indies.[18] As a result of Carroll's letters to Catholic families across the country, Georgetown had a significantly more geographically diverse student body than other American colleges at the time.[19] To accommodate this increase, the college building was extended by 130 feet (40 m) and a third story was added.[18] Plunkett oversaw the division of the school into three parts: elementary, preparatory, and college.[19]

Plunkett increasingly preferred the plantation life of the former Jesuits in rural Maryland, and became dissatisfied with administering the college.[20] In December 1792, he submitted his resignation to Carroll, but agreed to remain until a replacement could be found. In June 1793, Carroll named Molyneux to succeed Plunkett as president.[20]

Later missionary years

Following the end of his tenure at Georgetown, Plunkett took up missionary work. Though living in Georgetown, he traveled regularly on horseback throughout Montgomery County, Maryland, where he was given charge of the congregations in Rock Creek, Rockville, Seneca, Barnesville, and Holland's River.[2] He was later stationed in Prince George's County, Maryland,[21] including for a time as pastor of the church in Bladensburg.[22] He was also in charge of Queen's Chapel,[11] a Catholic chapel built on the Queen family estate in Prince George's County.[23]

Despite his preference for rural ministry, Plunkett continued to remain involved in Georgetown College's affairs.[2] When the school was at a deficit of funds for the completion of the Old North Building in 1797, Plunkett donated a sum to aid its opening.[24] He was also named as one of five original members of Georgetown's board of directors, upon its creation in 1797;[25] he would remain a director until 1808.[26] These directors took measures to reduce the influence of the Sulpicians at the college, one of whom, Louis William Valentine Dubourg, became president of the school.[27]

Plunkett died on January 15, 1815, at Notley Hall in St. Mary's County, Maryland,[21] near the settlement of Chaptico.[28] He was interred in the crypt of the Georgetown Visitation Monastery.[21]

Notes

- The Corporation of Roman Catholic Clergymen of Maryland was created in 1792 in response to the suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1773 by Pope Clement XIV. Its purpose was to preserve the property of the former Jesuits with the hope that the Society would one day be restored and the property returned under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Jesuit superior in America.[12]

- The Spanish Inquisition was still ongoing at this time,[13] and the Canary Islands were possessions of the Spanish Empire.[14]

References

Citations

- Curran 1993, p. 32

- Warner 1994, p. 85

- Mattingly 2012, p. 153

- Hennesey 1990, p. 1

- Guilday 1922, p. 460

- Cichy 2017, p. 283

- Currier 1890, p. 62

- Currier 1890, p. 61

- Currier 1890, p. 60

- Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- Devitt 1909, p. 29

- Curran 2012, pp. 14–16

- Currier 1890, p. 64

- Currier 1890, p. 63

- Currier 1890, p. 66

- Curran 1993, p. 31

- Curran 1993, p. 33

- Curran 1993, p. 34

- O'Neill & Williams 2003, p. 16

- Curran 1993, p. 44

- Devitt 1905, p. 226

- Calvert 1991, p. 100

- Malesky, Robert (July 6, 2014). "Brookland Roads: Just where was Queen's Chapel?". Bygone Brookland. Archived from the original on March 9, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Curran 1993, p. 46

- Warner 1994, p. 27

- Curran 1993, p. 402

- Curran 1993, p. 51

- Bauer, King & Strickland 2013, p. 1

Sources

- Bauer, Skylar A.; King, Julia A.; Strickland, Scott M. (2013). Archaeological Investigations at Notley Hall, Near Chaptico, Maryland (PDF) (Report). St. Mary's City, Maryland: St. Mary's College of Maryland. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Calvert, Rosalie Stier (1991). Callcott, Margaret Law (ed.). Mistress of Riversdale: The Plantation Letters of Rosalie Stier Calvert. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-4093-7. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cichy, Andrew (2017). "Chapter 10: Parlour, Court and Cloister: Musical Culture in English Convents during the Seventeenth Century". In Bowden, Caroline; Kelly, James E. (eds.). The English Convents in Exile, 1600–1800: Communities, Culture and Identity. Catholic Christendom, 1300–1700. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-03402-5. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curran, Robert Emmett (1993). The Bicentennial History of Georgetown University: From Academy to University, 1789–1889. 1. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 978-0-87840-485-8. Archived from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curran, Robert Emmett (2012). "Ambrose Maréchal, the Jesuits, and the Demise of Ecclesial Republicanism in Maryland, 1818–1838". Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 13–158. ISBN 978-0-8132-1967-7. Archived from the original on September 9, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Currier, Charles Warren (1890). Carmel in America: A Centennial History of the Discalced Carmelites in the United States. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co. Retrieved January 25, 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Devitt, Edward I. (September 1905). "The Suppression and Restoration of the Society in Maryland" (PDF). Woodstock Letters. XXXIV (2): 203–235. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 21, 2020. Retrieved March 21, 2020 – via Jesuit Archives.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Devitt, Edward I. (1909). "Georgetown College in the Early Days". Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 12: 21–37. JSTOR 40066991.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guilday, Peter (1922). The Life and Times of John Carroll. New York: The Encyclopedia Press. OCLC 503430666. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hennesey, James (1990). "Neither the Bourbons nor the Revolution: Georgetown's Jesuit Founders". In Morris, Michèle R. (ed.). Images of America in Revolutionary France. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. pp. 1–12. ISBN 978-0-87840-497-1. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mattingly, Paul H. (Summer 2012). "A Maryland Jesuit in Eighteenth-Century Europe" (PDF). Maryland Historical Magazine. 107 (2): 141–154.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Neill, Paul R.; Williams, Paul K. (2003). Georgetown University. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-1509-0. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Warner, William W. (1994). At Peace with All Their Neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the National Capital, 1787–1860. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. ISBN 0-87840-557-7. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2020 – via Google Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

| Academic offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New office | 1st President of Georgetown College 1791–1793 |

Succeeded by Robert Molyneux |