Siege of Orléans

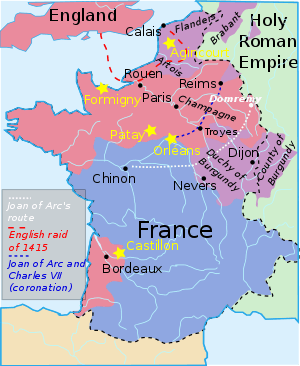

The Siege of Orléans (12 October 1428 – 8 May 1429) was the watershed of the Hundred Years' War between France and England. It was the French royal army's first major military victory to follow the crushing defeat at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, and also the first while Joan of Arc was with the army.[lower-alpha 2] The siege took place at the pinnacle of English power during the later stages of the war. The city held strategic and symbolic significance to both sides of the conflict. The consensus among contemporaries was that the English regent, John of Lancaster, would have succeeded in realizing his brother the English king Henry V's dream of conquering all of France if Orléans fell. For half a year the English and their French allies appeared to be winning but the siege collapsed nine days after Joan's arrival.

| Siege of Orléans | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

Joan of Arc at the Siege of Orléans by Jules Eugène Lenepveu, painted 1886–1890 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

5,000[1][2] • c. 3,263–3,800 English[3] • 1,500 Burgundians[3][lower-alpha 1] |

6,400 soldiers 3,000 armed citizens[1][2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| more than 4,000[1] | 2,000[1] | ||||||

Background

Hundred Years' War

The siege of Orléans occurred during the Hundred Years' War, contested between the ruling houses of France and England for supremacy over France. The conflict had begun in 1337 when England's King Edward III decided to press his claim to the French throne, a claim based on his being the son of Isabella of France and thus of the contested French royal line.

Following a decisive victory at Agincourt in 1415, the English gained the upper hand in the conflict, occupying much of northern France.[4] Under the Treaty of Troyes of 1420, England's Henry V became regent of France. By this treaty, Henry married Catherine, the daughter of the current French king, Charles VI, and would then succeed to the French throne upon Charles's death. The Dauphin of France (title given to the French heir apparent), Charles, the son of the French king, was then disinherited.[5]

Geography

Orléans is located on the Loire River in north-central France. During the time of this siege it was the northernmost city that remained loyal to the Valois French crown. The English and their Burgundian allies controlled the rest of northern France, including Paris. Orléans's position on a major river made it the last obstacle to a campaign into central France. England already controlled France's southwestern coast.

Armagnac party

As the capital of the duchy of Orléans, this city held symbolic significance in early 15th century politics. The dukes of Orléans were at the head of a political faction known as the Armagnacs, who rejected the Treaty of Troyes and supported the claims of the disinherited and banished Dauphin Charles to the French throne. This faction had been in existence for two generations. Its leader, the Duke of Orléans, also in line for the throne, was one of the very few combatants from Agincourt who remained a prisoner of the English fourteen years after the battle.

Under the customs of chivalry, a city that surrendered to an invading army without a struggle was entitled to lenient treatment from its new ruler. A city that resisted could expect a harsh occupation. Mass executions were not unknown in this type of situation. By late medieval reasoning, the city of Orléans had escalated the conflict and forced the use of violence upon the English, so a conquering lord would be just in exacting vengeance upon its citizens. The city's association with the Armagnac party made it unlikely to be spared if it fell.

Preparations

State of the conflict

After the brief fallout over Hainaut in 1425–26, English and Burgundian arms renewed their alliance and offensive on the Dauphin's France in 1427.[6] The Orléanais region southwest of Paris was of key importance, not only for controlling the Loire river, but also to smoothly connect the English area of operations in the west and the Burgundian area of operations in the east. French arms had been largely ineffective before the Anglo-Burgundian onslaught until the siege of Montargis in late 1427, when they managed to successfully force it to be lifted. The relief of Montargis, the first effective French action in years, emboldened sporadic uprisings in the thinly-garrisoned English-occupied region of Maine to the west, threatening to undo recent English gains.[7]

However, the French failed to capitalize on the aftermath of Montargis, in large part because the French court was embroiled in an internal power struggle between the constable Arthur de Richemont and the chamberlain Georges de la Trémoille, a new favourite of the Dauphin Charles.[8] Of the French military leaders, John, the "Bastard of Orléans" (later called "Dunois"), La Hire and Jean de Xaintrailles were partisans of La Trémoille, while Charles of Bourbon, Count of Clermont, the marshal Jean de Brosse and John Stewart of Darnley (head of the Scottish auxiliary forces), were lined up with the constable.[9][10] The inner French conflict had reached such a point that their partisans were fighting each other in the open field by mid-1428.[9]

The English availed themselves of French paralysis to raise fresh reinforcements in England in early 1428, raising a new force of 2,700 men (450 men-at-arms and 2,250 longbowmen), brought over by Thomas Montacute, 4th Earl of Salisbury,[8] who was regarded as the most effective English commander of the time.[11] These were bolstered by new levies raised in Normandy and Paris,[12] and joined by auxiliaries from Burgundy and vassal domains in Picardie and Champagne, to a total strength possibly as great as 10,000.

At the council of war in the spring of 1428, the English regent John, Duke of Bedford determined the direction of English arms would be towards the west, to stomp out the fires in the Maine and lay siege to Angers.[13] The city of Orléans was not originally on the menu – indeed, Bedford had secured a private deal with Dunois,[12] whose attentions were focused on the Richemont-La Trémoille conflict, then raging violently in the Berri. As Charles, Duke of Orléans was at the time in English captivity, it would have been contrary to the customs of knightly war to seize the possessions of a prisoner. Bedford agreed to leave Orléans alone, but, for some reason, changed his mind shortly after the arrival of English reinforcements under Salisbury in July 1428. In a memorandum written in later years, Bedford expressed that the siege of Orléans "was taken in hand, God knoweth by what advice",[14] suggesting it was probably Salisbury's idea, not his.[15]

Salisbury's approach

Between July and October, the Earl of Salisbury swept through the countryside southwest of Paris – recovering Nogent-le-Roi, Rambouillet and the area around Chartres.[13] Then, rather than continuing southwest to Angers, Salisbury turned abruptly southeast towards Orléans instead. Pressing towards the Loire, Salisbury seized Le Puiset and Janville (with some difficulty) in August. From there, rather than descending directly on Orléans from the north, Salisbury skipped over the city to seize the countryside west of it. He reached the Loire river at Meung-sur-Loire, which he promptly seized (a detachment of his men crossed the river then to plunder the abbey of Cléry).[13][16] He pressed a little downriver, in the direction of Blois, to take the bridge and castle of Beaugency.[13] Salisbury crossed the Loire at the point, and turned up to approach Orléans from the south. Salisbury arrived at Olivet, just one mile south of Orléans, on October 7.[12] In the meantime, an English detachment, under John de la Pole, had been sent to seize the regions upriver, east of Orléans: Jargeau fell on October 5,[13] Châteauneuf-sur-Loire immediately after, while further upriver, the Burgundians took Sully-sur-Loire.[12] Orléans was cut off and surrounded.

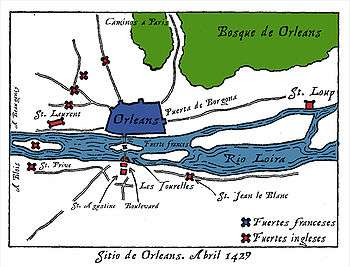

Manning the defenses of Orléans, John of Dunois had watched the tightening English noose and took care to prepare the city for siege. Dunois correctly anticipated that the English would aim for the bridge, nearly 1⁄4 mile (400 m) long, that led from the south shore of the Loire into the centre of the city of Orléans on the north shore. The bridge passed over the riverine island of St. Antoine, an optimal location for Salisbury to position English cannon within range of Orléans city centre.[12] At the southern end of the bridge was a turreted gatehouse, Les Tourelles, which stood in the river, connected by a drawbridge to the southern bank. Dunois rapidly erected a large earthwork bulwark (Boulevart) on the south shore itself, which he packed with the bulk of his troops, thus creating a large fortified complex to protect the bridge.[17] Just across from the Boulevart was an Augustinian friary, which could be used as a flanking firing position on any approach to the bridge, although it seems Dunois decided not to make use of it. On his orders, the southern suburbs of Orléans were evacuated and all structures leveled to prevent giving the English cover.[17]

Early stages of the siege

Assault on the Tourelles

.jpg)

The siege of Orléans formally began on 12 October 1428, and initiated with an artillery bombardment that began on 17 October. The English assaulted the Boulevart on 21 October, but the assaulters were held back by French missile fire, rope nets, scalding oil, hot coals and quicklime.[17][18] The English decided against a new frontal attack, and set about mining the bulwark. The French countermined, fired the pit props and fell back to the Tourelles on 23 October. But the Tourelles itself was taken by storm the next day, 24 October.[17] The departing French blew up some of the bridge arches to prevent a direct pursuit.

With the fall of the Tourelles, Orléans seemed doomed. But the timely arrival of the Marshal de Boussac with sizeable French reinforcements prevented the English from repairing and crossing the bridge and seizing Orléans right then.[17] The English suffered another setback two days later, when the Earl of Salisbury was struck in the face by debris kicked up in cannon fire while supervising the installation of the Tourelles. English operations were suspended while Salisbury was carried off to Meung to recover, but after lingering for about a week, he died of his injuries.[19][20]

The investment

The lull in English operations following Salisbury's injury and death gave the citizens of Orléans time to knock out the remaining arches of the bridge on their end, disabling the possibility of a quick repair and direct assault. The new siege commander appointed by Bedford in mid-November, William de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk resolved on surrounding the city and starving it into submission. He did not have enough men to invest the city with continuous trenchlines, so he set up a series of outworks, (bastides). Over the next few months, seven strongholds were set up on the north bank, and four on the south bank, with the small riverine isle of Charlemagne (west of Orléans) commanding the bridges connecting the two banks.[21]

In the winter, a Burgundian force numbering about 1,500 men arrived to support the English besiegers.

The establishment of the outworks was not without difficulty – the French garrison sallied out repeatedly to harass the builders, and systematically destroyed other buildings (notably, all the churches) in the suburbs to prevent them serving as shelter for the English during the winter months. By the Spring of 1429, the English outworks covered only the south and west of the city, with the northeast basically left open (nonetheless swarming with English patrols). Sizeable contingents of French men-at-arms could push aside the patrols and move in and out of the city, but the entry of any lighter-escorted provisions and supplies was firmly blocked, there and further afield.[21]

On the south bank, the English center was the bridge complex (composed of the Tourelles-Boulevart and the now-fortified Augustins). Guarding the approach to the bridge from the east was the bastille of St. Jean-le-Blanc, while to the west of the bridge complex was the bastille of Champ de St. Privé. St. Privé also guarded the bridge to the island of Charlemagne (which had another bastille). On the north bank of the Loire river, on the other side of Charlemagne bridge, was the bastille of St. Laurent, the largest English bulwark and the nerve center of English operations. Above that were a series of smaller outworks, in order: the bastille de la Croiz Boisse, the bastille des Douze Pierres (nicknamed "London"), the bastille de Pressoir Aps (nicknamed "Rouen") and, just north of the city, the bastille de St. Pouair (nicknamed "Paris"), all on top of the main roads.[22] Then came the great northeastern gap, although its back was mostly covered by thick forest of the Bois d'Orléans. Finally, some 2 km east of the city, on the north bank, there was the isolated bastille of St. Loup.

Orléans's position seemed gloomy. Although the French still held isolated citadels like Montargis to the northeast and Gien upriver,[23] any relief would have to come from Blois, to the southwest, exactly where the English had concentrated their forces. Provisions convoys had to follow dangerous circuitous routes swinging around to reach the city from the northeast. Few made it through, and the city soon began to feel the pinch. Should Orléans fall, it would effectively make the recovery of the northern half of France all but impossible, and prove fatal to the Dauphin Charles's bid for the crown. When the French Estates met at Chinon in September 1428, they pressed the Dauphin to make peace with Philip III of Burgundy "at any price".[24]

Battle of the Herrings

The threat to Orléans had prompted the partisans of Richemont and La Trémoille to make a quick temporary truce in October 1428. In early 1429, Charles de Bourbon, Count of Clermont assembled a French-Scottish force in Blois for the relief of Orléans.[25][26] Hearing of the dispatch of an English supply convoy from Paris, under the command of Sir John Fastolf for the English siege troops, Clermont decided to take a detour to intercept it. He was joined by a force from Orléans under John of Dunois, which had managed to slip past the English lines. The forces made junction at Janville and attacked the English convoy at Rouvray on 12 February, in an encounter known as the Battle of the Herrings, on account of the convoy being laden with a large supply of fish for the forthcoming Lenten season.[27][28]

The English, aware of their approach, formed a "laager" with the supply wagons, lining the circumference with bowmen. Clermont ordered the French to hold back, and let their cannon do the damage. But the Scottish regiments, led by John Stewart of Darnley, dissatisfied with the missile duel, decided to move in. The French lines hesitated, uncertain of whether to follow or remain back as ordered. Seeing the French immobilized or only timidly following, the English sensed an opportunity. The English cavalry burst out of the wagon fort, overwhelmed the isolated Scots, and threw back the hesitant French. Disorder and panic set in, and the French fell into retreat. Stewart of Darnley was killed, John of Dunois wounded. Fastolf brought the supplies in triumph to the English soldiers at Orléans three days later.[29]

The defeat at Rouvray was disastrous for French morale. Bickering and recriminations immediately followed as Clermont and Dunois blamed each other for the disaster, reopening the fissures between the Richemont and La Tremoille parties. Clermont, disgusted, quit the field and retired to his estates, refusing to participate further.[29] Once again, the Dauphin Charles was advised to sue for peace with Burgundy and should that fail, to consider abdicating and retiring to the Dauphiné, perhaps even going into exile in Scotland.[29]

Surrender proposal

In March, John of Dunois made an irresistible offer to Philip III of Burgundy, offering to turn Orléans over to him, to hold as a neutral territory on behalf of his captive half-brother Charles, Duke of Orléans.[30] A group of nobles and bourgeois from the city went to Philip to try to make him persuade the Duke of Bedford to lift the siege so that Orléans could surrender to Burgundy instead. The specific terms of the offer made are outlined in the letter by a contemporary merchant. Burgundy would be able to appoint the city's governors on behalf of the Duke of Orléans, half the city's taxes would go to the English, the other half would go for the ransom of the imprisoned duke, a contribution of 10,000 gold crowns was to be made to Bedford for war expenses, and the English would gain military access through Orléans, all in return for lifting the siege and handing the city to the Burgundians.[31]

The agreement would have given the English the chance to pass through Orléans and strike into Bourges, the administrative capital of the Dauphin, which had been the primary motivator for the siege itself. Burgundy hurried to Paris in early April to persuade the English regent John of Bedford to take the offer. But Bedford, certain Orléans was on the verge of falling, refused to surrender his prize. The disappointed Philip withdrew his Burgundian auxiliaries from the English siege in a huff.[32] The Burgundian contingent left on 17 April 1429,[33] which left the English with an extremely small army to prosecute the siege. The decision proved to be a lost opportunity, and a terrible mistake in the long run for the English.[34]

Joan's arrival at Orléans

It was on the very day of the Battle of the Herrings that a young French peasant girl, Joan of Arc, was meeting with Robert de Baudricourt,[35] the Dauphinois captain of Vaucouleurs,[36] trying to explain to the skeptical captain her divinely-ordained mission to rescue the Dauphin Charles and deliver him to his royal coronation at Reims. She had met and been rebuffed by Baudricourt twice before, but apparently this time he assented and arranged to escort her to the Dauphin's court in Chinon. According to the Chronique de la Pucelle, at this meeting with Baudricourt, Joan disclosed that the Dauphin's arms had suffered a great reversal near Orléans that day, and if she were not sent to him soon, there would be others.[37] Accordingly, when news of the defeat at Rouvray reached Vaucouleurs, Baudricourt became convinced of the girl's prescience and agreed to escort her. Whatever the truth of the story – and it is not accepted by all authorities – Joan left Vaucouleurs on February 23 for Chinon.

For years, vague prophecies had been circulating in France concerning an armored maiden who would rescue France. Many of these prophecies foretold that the armored maiden would come from the borders of Lorraine, where Domrémy, Joan's birthplace, is located.[lower-alpha 3] As a result, when word reached the besieged citizens of Orléans concerning Joan's journey to see the King, expectations and hopes were high.

Escorted by Baudricourt, Joan arrived in Chinon on March 6 1429, and met with the skeptical La Trémoille. On March 9, she finally met the Dauphin Charles, although it would be a few days more before she had a private meeting where the Dauphin was finally convinced of her "powers" (or at least, her usefulness).[38] Nonetheless, he insisted she first proceed to Poitiers to be examined by church authorities. With the clerical verdict that she posed no harm and could be safely taken on, Dauphin Charles finally accepted her services on March 22. She was provided with a suit of plate armor, a banner, a pageboy, and heralds.

Joan's first mission was to join a convoy assembling at Blois, under the command of Marshal Jean de La Brosse, Lord of Boussac bringing supplies to Orléans. It was from Blois that Joan dispatched her famous missives to the English siege commanders, calling herself "the Maiden" (La Pucelle), and ordering them, in the name of God, to "Begone, or I will make you go".[39]

The relief convoy, escorted by some 400–500 soldiers, finally left Blois on 27 or 28 April, in nearly religious processional array. Joan had insisted on approaching Orléans from the north (through the Beauce region), where English forces were concentrated, intent on fighting them immediately. But the commanders decided to take the convoy in a circuitous route around the south (through the Sologne region) without telling Joan, reaching the south bank of the Loire at Rully (near Chécy), some four miles east of the city. Orléans' commander, Jean de Dunois, came out to meet them across the river. Joan was indignant at the deception and ordered an immediate attack on St. Jean-le-Blanc, the nearest English bastille on the south bank. But Dunois, supported by the Marshals, protested and with some effort, finally prevailed on her to allow the city to be resupplied before any assaults on anything. The provisions convoy approached the landing of Port Saint-Loup, across the river from the English bastille of Saint-Loup on the north bank. While French skirmishers kept the English garrison of Saint-Loup contained, a fleet of boats from Orléans sailed down to the landing to pick up the supplies, Joan and 200 soldiers. One of Joan's reputed miracles was said to have taken place here: the wind which had brought the boats upriver suddenly reversed itself, allowing them to sail back to Orléans smoothly under the cover of darkness. Joan of Arc entered Orléans in triumph, on April 29, around 8:00 PM, to much rejoicing. The rest of the convoy returned to Blois.

Lifting the siege

Over the next couple of days, to boost morale, Joan paraded periodically around the streets of Orléans, distributing food to the people and salaries to the garrison. Joan of Arc also sent out messengers to the English bastions demanding their departure, which the English commanders greeted with jeers. Some even threatened to kill the messengers as "emissaries of a witch".

Joan participated in discussion of tactics with John of Dunois and the other French commanders. The Journal du siege d'Orléans, as quoted in Pernoud, reports several heated discussions over the next week concerning military tactics between Joan and Jean de Dunois, the Bastard of Orléans, who directed the city's defense.

Believing the garrison too small for any action, on May 1, Dunois left the city in the hands of La Hire and made his way personally to Blois to arrange for reinforcements. During this interlude, Joan went outside the city walls and surveyed all of the English fortifications personally, at one point exchanging words with William Glasdale himself.

On May 3, Dunois's reinforcement convoy left Blois to head for Orléans. At the same time, other troop convoys set out from Montargis and Gien in the direction of Orléans. Dunois's military convoy arrived via the Beauce district, on the north bank of the river, in the early morning of May 4, in full view of the English garrison at St. Laurent. The English declined to challenge the convoy's entry on account of its strength. Joan rode out to escort it in.

Assault on St. Loup

At noon that same day (May 4, 1429), apparently to secure the entry of more provisions convoys, which had taken the usual circuitous route via the east, Dunois launched an attack on the easterly English bastille of St. Loup together with the Montargis-Gien troops. Joan nearly missed out on it, having been napping when the assault began, but she hurried to join in.[40] The English garrison of 400 was heavily outnumbered by the 1,500 French attackers. Hoping to divert the French away, the English commander, Lord John Talbot, launched an attack from St. Pouair, on the northern end of Orléans, but it was held back by a French sortie. After a few hours, St. Loup fell, with some 140 English killed and 40 prisoners taken. Some of the English defenders of St. Loup were captured in the ruins of a nearby church, their lives spared at Joan's request. Hearing that St. Loup had fallen, Talbot retired the northern assault.

Assault on the Augustines

The next day, May 5, was Ascension Day, and Joan urged an attack on the largest English outwork, the bastille of St. Laurent to the west. But the French captains, knowing its strength and that their men needed rest, prevailed on her to allow them to honor the feast-day in peace. [41] Overnight, in a war council, it was decided that the best course of action was to clear the English bastions on the south bank, where the English were weakest.

The operation began in the early morning of May 6. The citizens of Orléans, inspired by Joan of Arc, raised urban militias on her behalf and showed up at the gates, much to the distress of the professional commanders. Nonetheless, Joan prevailed upon the professionals to allow the militia to join. The French crossed the river from Orléans on boats and barges and landed on the island of St. Aignan, crossing over to the south bank via a makeshift pontoon bridge, landing on the stretch between the bridge complex and the bastille of St. Jean-le-Blanc. That plan had been to cut off and take St. Jean-le-Blanc from the west, but the English garrison commander, William Glasdale, sensing the intent of the French operation, had already hurriedly destroyed the St. Jean-le-Blanc outwork and concentrated his troops in the central Boulevart-Tourelles-Augustines complex.

Before the French had properly disembarked on the south bank, Joan of Arc reportedly launched a precipitous attack on the strongpoint of the Boulevart. This nearly turned into a disaster, as the assault was exposed on the flanks to English fire from the Augustines. The assault broke off when there were cries that the English garrison of the bastille of St. Privé further west was rushing upriver to reinforce Glasdale and cut them off. Panic set in, and the French attackers retreated from the Boulevart back to the landing grounds, dragging Joan back with them. Seeing the "witch" on the run and the "spell" broken, Glasdale's garrison burst out to give chase, but according to legend, Joan turned around on them alone, raised her holy standard and cried out "Au Nom De Dieu" ("In the name of God"), which reportedly was sufficient to impress the English to halt their pursuit and return to the Boulevart.[42] The fleeing French troops turned around and rallied to her.

Watching the turn of events, Gilles de Rais persuaded Joan to immediately resume the assault, but to direct the French soldiers not on the Boulevart, but rather on the detached bastille of the Augustins. After heavy fighting that lasted the entire day, the Augustins was finally taken just before nightfall.

With the Augustins in French hands, Glasdale's garrison was blockaded in the Tourelles complex. That same night, what remained of the English garrison at St. Privé evacuated their outwork and went north of the river to join their comrades in St. Laurent. Glasdale was isolated, but he could count on a strong and well-ensconced English garrison of 700–800 troops.

Assault on the Tourelles

Joan had been wounded in the foot in the assault on the Augustins, and taken back to Orléans overnight to recover, and as a result did not participate in the evening war council. The next morning, May 7, she was asked to sit out the final assault on the Boulevart-Tourelles, but she refused and roused to join the French camp on the south bank, much to the joy of the people of Orléans.[43] The citizens raised more levies on her behalf and set about repairing the bridge with beams to enable a two-sided attack on the complex. Artillery was positioned on the island of Saint-Antoine.

The day was spent in a largely fruitless bombardment and attempts to undermine the foundations of the complex, by mining and burning barges. As evening was approaching, Jean de Dunois had decided to leave the final assault for the next day. Informed of the decision, Joan called for her horse and rode off for a period of quiet prayer, then returned to the camp, grabbed a ladder and launched the frontal assault on the Boulevart herself, reportedly calling out to her troops "Tout est vostre – et y entrez!" ("All is yours, – go in!").[44] The French soldiery rushed in after her, swarming up the ladders into the Boulevart. Joan was struck down early in the assault by a longbow arrow between the neck and left shoulder and was hurriedly taken away. Rumors of her death bolstered the English defenders and faltered French morale. But, according to eyewitnesses, she returned later during the evening and told the soldiers that a final assault would carry the fortress. Joan's confessor / chaplain, Jean Pasquerel, later stated that Joan herself had some type of premonition or foreknowledge of her wound, stating the day before the attack that "tomorrow blood will flow from my body above my breast."[45]

The French carried the day and forced the English out of the boulevart and back into the last redoubt of the Tourelles. But the drawbridge connecting them gave way, and Glasdale himself fell into the river and perished.[46] The French pressed on to storm the Tourelles itself, from both sides (the bridge now repaired). The Tourelles, half-burning, was finally taken in the evening.

English losses were heavy. Counting other actions on the day (notably the interception of reinforcements rushed to the defense), the English had suffered nearly a thousand killed, and 600 prisoners. 200 French prisoners were found in the complex and released.

End of the siege

With the Tourelles complex taken, the English had lost the south bank of the Loire. There was little point of continuing the siege, as Orléans could now be easily re-supplied indefinitely.

On the morning of May 8, the English troops on the north bank, under the command of the Earl of Suffolk and Lord John Talbot, demolished their outworks and assembled in battle array in the field near St. Laurent. The French army under Dunois lined up before them. They stood facing each other immobile for about an hour, before the English withdrew from the field and marched off to join other English units in Meung, Beaugency and Jargeau. Some of the French commanders urged an attack to destroy the English army then and there. Joan of Arc reportedly forbade it, on account of it being Sunday.[47]

Aftermath

The English did not consider themselves beaten. Although they had suffered a setback and tremendous losses at Orléans itself, the surrounding perimeter of the Orleanais region – Beaugency, Meung, Janville, Jargeau – was still in their hands. Indeed, it was possible for the English to reorganize and resume the siege of Orléans itself soon after, this time perhaps with more success, as the bridge was now repaired, and thus more susceptible to being taken by assault. Suffolk's priority that day (May 8) was to salvage what remained of English arms.

The French commanders realized as much, Joan less so. Leaving Orléans, she met the Dauphin Charles outside of Tours on May 13, to report her victory. She immediately called for a march northeast into Champagne, towards Reims, but the French commanders knew they had to first clear the English out of their dangerous positions on the Loire.

The Loire Campaign began a couple of weeks later, after a period of rest and reinforcement. Volunteers of men and supplies swelled the French army, eager to serve under Joan of Arc's banner. Even the ostracized constable Arthur de Richemont was eventually permitted to join the campaign. After a series of brief sieges and battles at Jargeau (June 12), Meung (June 15) and Beaugency (June 17), the Loire was back in French hands. An English reinforcement army rushing from Paris under John Talbot was defeated at the Battle of Patay shortly after (June 18), the first significant field victory for French arms in years. The English commanders, the Earl of Suffolk and Lord Talbot, were taken prisoner in this campaign. Only thereafter did the French feel safe enough to accede to Joan's request for a march on Reims.

After some preparation, the march on Reims began from Gien on June 29, the Dauphin Charles following Joan and the French army through the dangerous Burgundian-occupied territory of Champagne. Although Auxerre (July 1) closed its gates and refused them entry, Saint-Florentin (July 3) yielded, as did, after some resistance, Troyes (July 11) and Châlons-sur-Marne (July 15). They reached Reims the next day and the Dauphin Charles, with Joan at his side, was finally consecrated as King Charles VII of France on July 17, 1429.

Legacy

The city of Orléans commemorates the lifting of the siege with an annual festival, including both modern and medieval elements and a woman representing Joan of Arc in full armor atop a horse.[48] On May 8, Orléans simultaneously celebrates the lifting of the siege and V-E Day (Victory in Europe, the day that Nazi Germany surrendered to the Allies to end World War II in Europe.)

See also

- Medieval warfare

- The Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World

- Jean Poton de Xaintrailles

- Joan of Arc bibliography

Notes

- Burgundy withdrew its men on 17 April 1429 due to disagreements with its English allies, after which only the small English army remained to continue the siege.

- Joan earlier (5 May 1429) marched to the fortress of Saint Jean le Blanc. Finding it deserted, this became a bloodless victory. The next day, with the aid of only one captain she captured the fortress of Saint Augustins (Joan of Arc: Leadership).

- Domrémy was in the Duchy of Bar, right on the edge of the Duchy of Lorraine.

- Charpentier & Cuissard 1896, p. 410.

- Davis 2003, p. 76.

- Pollard 2005, p. 14.

- DeVries 1999, pp. 20–24.

- DeVries 1999, p. 26.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 374.

- Ramsay 1892, pp. 375–376.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 380.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 386.

- Beaucourt 1882, pp. 144–168.

- Jones 2000, p. 20.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 382.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 381.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 382 n. 2.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 398.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 257.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 383.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 261.

- Ramsay 1892, pp. 383–384.

- DeVries 1999, p. 61.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 384.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 265.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 387.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 386 n4.

- Ramsay 1892, pp. 385–386.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 266.

- DeVries 1999, pp. 65–66.

- "Battle of the Herrings". Xenophon Group. 1999-12-21. Archived from the original on 25 September 2017.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 386.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 269.

- Jones 2000, p. 24.

- Ramsay 1892, pp. 386–387.

- Pollard 2005, p. 15.

- Jones 2000, p. 26.

- DeVries 1999, pp. 67–68.

- DeVries 1999, p. 39.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 272. For contemporary testimonials of the meetings with Baudricourt given at Joan's trial, see Quicherat's Procès, vol. 1 p. 53, vol. 2 pp. 436, 456.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 390; Beaucourt 1882, pp. 204–09.

- For the letters, see Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 281

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 288.

- Ramsay 1892, p. 393. This is according to Cousinot's Pucelle (pp. 289–290). However, Jean Pasquerel (in Quicherat's Procès vol. 3, p. 107) differs, and seems to suggest the suspension for Ascension Day was originally Joan's idea.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, pp. 290–291; Ramsay 1892, p. 394.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, pp. 291–292.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 293.

- Quicherat's 1845 Procès, p. 109. Note that Cousinot's Pucelle (p. 293) separates the events, and reports that Joan was wounded in an earlier morning assault, and only after her recovery made the decision to initiate the afternoon assault.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 294.

- Cousinot's Pucelle, p. 296.

- Fêtes de Jeanne d'Arc (Festivals of Joan of Arc, Orleans) – May 8, 2016 Photos Orleans & son AgglO

References

- Beaucourt, G.F. (1882). Histoire de Charles VII, 2: Le Roi de Bourges 1422–1435 (PDF) (in French). Paris: Société Bibliographique. Archived.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Charpentier, Paul & Cuissard, Charles (1896). Journal du siège d'Orléans, 1428–1429. H. Herluison.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cousinot de Montreuil, G. (1864). M. Vallet de Viriville (ed.). Chronique de la Pucelle ou chronique de Cousinot. Paris: Delays. link

- Davis, P.K. (2003-06-26). Besieged: 100 great sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-521930-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- DeVries, K. (1999). Joan of Arc: a Military Leader (PDF). Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-1805-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, M.K. (2000). "'Gardez mon corps, sauvez ma terre' – Immunity from War and the Lands of a Captive Knight: The Siege of Orléans (1428–29) Revisited". In Mary-Jo Arn (ed.). Charles d'Orléans in England (1415–1440). D.S. Brewer. pp. 9–26. ISBN 978-0-85991-580-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pernoud, R. & Clin, Marie-Véronique (1998). Joan of Arc: her story. Translated and revised by Jeremy duQuesnay Adams, edited by Bonnie Wheeler. New York: St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 978-0-312-21442-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pollard, A.J. (2005-11-19). John Talbot and the War in France 1427–1453. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84415-247-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Quicherat, J. (1841). Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d'Arc dite La Pucelle. 1. Paris: Renouard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) link

- Quicherat, J. (1844). Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d'Arc dite La Pucelle. 2. Paris: Renouard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) link

- Quicherat, J. (1845). Procès de condamnation et de réhabilitation de Jeanne d'Arc dite La Pucelle. 3. Paris: Renouard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) link

- Ramsay, J.H. (1892). Lancaster and York: A century of English history (A.D. 1399–1485). 1. Oxford: Clarendon. Archived.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Cooper, Stephen (2010-09-20). The Real Falstaff: Sir John Fastolf and the Hundred Years' War. Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-123-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicolle, D. (2001-11-25). Orléans 1429: France turns the tide (PDF). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-232-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Siege of Orléans. |

- "Orleans, Siege of". eHistory. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2012.

- "Siege of Orléans". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Chapter on the Siege of Orleans

- Joan of Arc at Orleans description of the battle with numerous links to more detailed information

- St Joan of Arc and the Scots Connection the role of the Scots in the siege of Orleans

- The Siege of Orleans, BBC Radio 4 discussion with Anne Curry, Malcolm Vale & Matthew Bennett (In Our Time, May 24, 2007)