Retignano

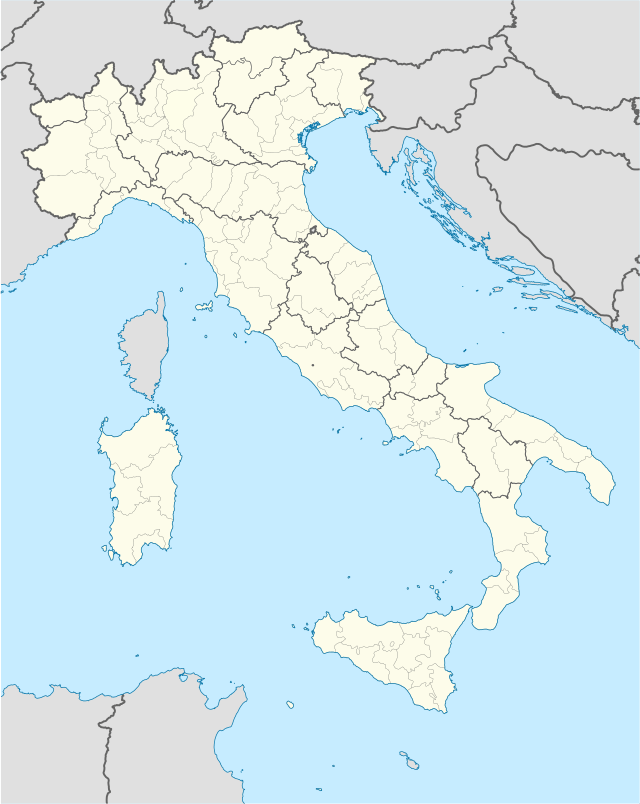

Retignano is a village of about 400 inhabitants, located on a hill in the historical Versilia, a northern area of the Italian region of Tuscany, in the municipality of Stazzema, about 430 meters above sea level. The inhabitants are called Retignanesi.

Retignano Retinius | |

|---|---|

The village in summer 2015 | |

Retignano Location of Retignano in Italy | |

| Coordinates: 44°0′18″N 10°16′23″E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Tuscany |

| Province | Lucca (LU) |

| Comune | Stazzema |

| Elevation | 430 m (1,410 ft) |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 381 |

| Demonym(s) | Retignanesi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 55040 |

| Dialing code | 0584 |

| Patron saint | St. Peter |

| Saint day | June 29 |

| Website | Official website |

At first it was a small settlement belonging to the Liguri Apuani, a small community coming from northern Europe. It then fell into the Roman Empire in the year 177 BCE, becoming one of the most flourishing and developed Roman settlements in the area, on the Apuan Alps. It was mainly used as a hideout, in the event of an imminent attack from the sea, since it was a known stronghold of sighting of the enemies coming from the sea and strategic point of supply of timber, various extractive materials and marble. After a period of independence in the guise of “little municipality”, which lasted several centuries, in 1776 the Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo subtracted this title from the village, subjecting it to the dominion of Lucca, whose province Retignano is now part of. Retignano returned to prosper in the second half of the nineteenth century thanks to the opening of the marble quarries, mining sites of the prized "bardiglio fiorito", appreciated especially by the English, the same financiers of the project. In the period between the two world wars, the village experienced rapid depopulation, caused by emigration to large cities or to foreign countries, particularly North America or Argentina. Besieged by the Germans and exploited for its enviable position, it was then "reconquered" by the American soldiers who placed one of their main bases during the advancement phase at the Gothic Line.

History

First settlements: the Roman conquest

In the first centuries AD, because of the raids made by barbarian peoples, several forts were built in the current area of Retignano, many of which are still visible, although not easily accessible. The fort called "Pineta" still has loopholes and is open to the public, while others (especially those of the "roso" and the "casino") have been converted into marginette (small huts with a religious engraving or image, used to rest for a while and/or to pray) or metati, that is chestnut processing houses to get flour and other types of food.

The origins of the village date back to the twenty years between 560 and 580 AD,[1] in the late Roman age, in which the militias of Rome fought against the Ligurian Apuans, a population of the Apuan Alps. It is believed, in fact, that even then there was a small group of huts surrounded by many fields, some of which were shared with other nearby settlements of Terrinca and Levigliani, where they have found traces of this population.[2] Furthermore, Retignano shared with Levigliani a sort of necropolis, digged in the mountains.[2]

For many centuries the Ligurian Apuans had to battle against the Romans to keep their possessions in Versilia. Most of the times they suffered heavy defeats because they were not so "on the edge" in weapons. However, historians believe that not all of them were deported in southern Italy during the period from 177 to 155 BC, probably because Rome was more interested in restraining these nomads away from the coast and the valley of Magra river, since they were a property of the Romans and the Apuans were just deemed as a threat to safety of the port of Luni and its trading importance.[3] For this reason, in 560 AD, some of the Ligurian Apuans still lived in Versilia and founded tiny villages still nowadays inhabited or still visible.

The Ligurian-Apuans, or simply Apuans, were a population divided into various tribes, called Nomens (names) by Roman historians; one of them settled between the mountains of Mont'Alto, a very large area, surrounded by natural boundaries (such as woods and streams) and full of resources, including medicinal plants and wildlife. Here the Apuan lived a semi-nomadic life and exploiting the area of Retignano as a settlement from spring until early winter. In more sheltered areas and clearings like "Gordici" and "Valimoni", places of Retignano located in the woods, about 700 meters above the sea level, there were the remais of smaller settlements called by the Apuans luki (turned in Latin into loci, plural of locus which stands for "place"). In case of war, they always had a safe-conduct to a fortified summit from which they could see the horizon, being able to warn in time their compatriots of the arrival of the enemy. For Retignano, this summit coincides with the top of the mountain Castello ("castle"), whose etimology probably is to relate with this habit. From there you can see the entire valley and the coast of Versilia; on clear days, even a glimpse of the Tuscan archipelago can be caught. The gaps left by Roman historiography do not allow us to identify the tribes that populated Retignano. It is believed that they were the Vasates, inhabitants of Basati, a place in front of Retignano.[4]

After the defeat in the 6th century AD, the Ligurian Apuans were deported or, at least, expelled from Versilia. Their dominions in Retignano, Levigliani and Seravezza were divided firstly into colonies (coloniae in Latin), with Luni as the main center for Seravezza and Querceta, while Lucca for the mountain areas of Stazzema and Pietrasanta. The colonies were then divided into villages, which were built on hills easily accessible. Each of them became a Roman camp and took its name from its founder or governor.[1] The current name of Retignano comes, therefore, from the time of Roman rule.[5][6]

Some research on a document dated (31 August 855 AD) trace the name to Retinio, who was given the Roman district of the country which became Ratiniana, Ratignano, San Pietro di Retignano and finally Retignano (sometimes misspelled Ritignano).[1][2][5] The reference to the patron dates back to 700 AD, when Christianity became more widespread throughout the peninsula and Retignano too. The village, which was under the control of Roma, took its same patron (St. Peter, whose celebration day is on June, 29). On July 1, 932 A.D., the village, called Ratignano as evidenced by certain records of the Archbishop of Lucca, was donated by the Lombard king Lothair to Lucca.[2][7] On September 2, 954 AD, the country was already important and shortly thereafter became a comunello (a small municipality). At the time, its economy was largely based on agriculture and livestocks.

From the 11th century to the 17th century

The first area to be inhabited, after the period of the Apuan Ligurians, was a gather of huts beneath fields and waters, now called "Caldaia" in Italian (boiler in English) along with "la Corte" (the Court), so named because it used to be the primary seat of the first Comunello ("municipality") of Retignano and surrounding towards the end of 1100.

An essay on the history and the political configuration of Versilia and Tuscany in general, confirms that the mountain that overlooks Retignano, known as il Castello (the Castle) was once an ancient fortress useful for sighting enemies approaching and served as a division between the religious dominions of Luni and Lucca.

The Comunello of Retignano included, in addition to the village itself, the territories of Ruosina, "Argentiera" and Gallena, plus a series of settlements beyond the river, that people today call "dal fiume inna'" (in the local dialect it means "beyond the river"), to emphasize that they do not have a real name since for ages they were undere the rule of Retignano.

Guido from Vallecchia, in his Memoriales of 1264, tells us that in the village, already owned by the Nobles of Versilia in the thirteenth century, they grew wheat, barley, millet and chestnuts. In the statute of the Republic of Lucca, in 1308, it was determined that Retignano (note the name change) had to offer, on the day of the Holy Cross, a candle of four pounds. This offer, of little value, marked Retignano as a village of poor importance in Versilia's economy, since local comunelli tended to care only about themselves. Other records show that in 1401 in Retignano were active five masons and five weavers, while the majority of the inhabitants was devoted to agricultural crops.

1700

The Eighteenth century began with lots of new opportunities and a new-found economic prosperity that allowed the comunello to keep ruling for a while. In 1712 the popular council's representatives was composed of 50 people and it can be considered as the first real democratic administration. At that time, there were active four masons, six weavers, two insiders mills, a polishing and those who worked in carpentry and sawmills water. You can realize that the local government was led by a small elite, few workers who were pulling forward the local enonomy, while the main needs of the village and surroundings were a prerogative of the peasants.[2][7]

In 1720 they developed a profitable production of silkworms, as the cocoons from Retignano were considered the best ones in Versilia. In that year Retignano consisted of 94 houses with 436 inhabitants, representing 88 families. That's a bit unusual, according to the census of 1750, where instead we record only 42 families for a total of 212 inhabitants living in 46 houses. This discrepancy of data suggests that the previous records were related to all the villages and not only to Retignano.

At the beginning of the 1760s, we have the first signs of the impending "closure" of those little municipality, such as those of Retignano and Levigliani, whose prosperity lasted until June 17, 1776, when the Grand Duke of Tuscany Pietro Leopoldo eliminated the comunelli and the government seat shifted from Retignano to Ruosina. At first, things couldn't get worse, as Ruosina wasn't ready for such a duty. That's why the municipality was then attributed only to Stazzema, still nowadays.[2][5][7]

1800

In 1820 a group of French and British entrepreneurs visited the Versilia, in Tuscany. While the French Boumond family settled in Riomagno, Seravezza, the Englishman James Beresford (in the archives often marked as Belessforte) and his partner Gybrin preferred Retignano. With the help of the inhabitants, in the summer of 1820 they found in the Canaletta ("little channel") cave a fine marble available only in the mountains of Retignano, an unusual mix of different types of local marble ("variegated", bice and flourished bardiglio).[2][7] They decided to start up a mining session and immediately sent to Britain by sea several blocks of marble, presumably in London, where some monuments are made of Versilian marble, such as Marble Arch. The sample sent to the salesmen in England was immediately appreciated by the British, who decided to start a business with Retignano. In 1821 the two entrepreneurs, Beresford and Grybrin, with local support, founded a company and they rented from Francesco Guglielmi, for nine years and with the fee of 6,000 crowns, a quarry (named Messette) whence the marble was sent to the United Kingdom. The inhabitants of Retignano were particularly active in contributing to the recovery of the marble industry in Versilia, reopening quarries also in the locality of Mount Gabro, Ajola, Gordici and Messette, all of those part of the quarries complex in Montalto, Retignano (see the section below). In 1845 the retignanesi argued that the British entrepreneur William Walton harmed the lands used for grazing and the collection of firewood and chestnuts. They opposed to him in order to leave the monopoly t Beresford and his fellows. When Italy finally got unified in 1861, the villagers were engaged in large part in the excavations and the economy became mostly linked to marble, with a gradual reduction of half of the cultivation of chestnuts and a reduction in land used to grow olive trees, potatoes and tomatoes.[2][7]

Twentieth century

During the years of the Great War (1915-1918 for Italy), but especially during the Second World War, many residents of Retignano chose to find their luck abroad, thus dispersing their origins in foreign countries. The main source of inspiration was the American continent, whereas many travelled to the United States. This phenomenon of emigration also concerned the whole Italy, at a time when, close to the Reconstruction, people wanted to improve their living conditions. Many retignanesi sought work in the cities and the phenomenon caused a significant decrease of the number of inhabitants.

In the village there are two main associations which bring together the citizenship: the centennial Retignano Mercy, founded in 1908, and the local "CRS", a bar-friends association.

1944

In the summer of 1944, at the height of World War II, Nazi tyranny was also extended to the inland Versilia, including the village of Retignano and its surroundings, exploited for its strategic position from which you can observe the whole valley and the Tyrrhenian Sea horizon. In addition, the whole area was part of the Gothic Line, used by the Nazi soldiers to rule over the whole central Italy. In late July 1944, Nazis spread an order for Retignano inhabitants displacement. The aim was to expel the residents from their homes and flush the partisans who took refuge in the woods, as well as facilitate the passage of the Gothic Line, and then proceed with the bombardment of the mountain.

From Bettina Federigi's diaries you can even imagine what was it like to be in such a dramatic situation.

Saturday, July, 29th 1944

Yesterday, at almost 6 pm, the Germans spread sheets reporting displacement order for the inhabitants. Time: until the first of August 1944. [...] All the people I know run away carrying with them only few things; the Germans start shooting with their gun machines [...], they already blasted two houses [...] How many people riversed in the streets, somebody's crying, somebody's screaming, calling, asking for a help. The German Command headquarter, where they issued the displacement sheet, was plenty of people and their stuff. Many cannot manage to avoid the queue and demand for their safety pass.— Bettina Federigi, an extract from her journal published in Versilia Linea Gotica, an historical research written by Fabrizio Federigi.

Shortly before the evacuation, the nearby villages of Sant'Anna and Farnocchia suffered attacks from the German soldiers arrived few hours before, soon rejected by the local Resistance partisans. In late July, moreover, much of Farnocchia houses had been set on fire. The inhabitants of Retignano, intimidated by the enemy threats and horrors that were consumed in the area, gathered that evening in the main church, to pray to the Santissima Annunziata, considered like a patron along with Saint Peter. The pastor at the time, Don Marco Giannetti from Azzano, wrote an invocation to the Virgin Mary to beg her to save the inhabitants and spare other villages from ravage:

« O Maria, a Te che tutto puoi, affidiamo la protezione di questo paese.

Salvalo, o Maria, nel periodo burrascoso che attraversiamo. 1º agosto 1944 »

« Oh Mary, you can do everything, we rely on you for this village protection.

Defend it, oh Mary, in this blusterous time we're facing. August, 1st, 1944 »

While the retignanesi were preparing to leave their homes, according to the stories told by the elders, unexpectedly there came a countermand that annulled the previous evacuation order. As a sign of gratitude, the inhabitants of Retignano made offerings to the Virgin Mary, since then considered the protector of the village. The testimony of these facts lies in a carta gloriae kept in the sacristy of the church. Until a few years ago, on the 1° of August, the sacred image of the Virgin Mary was exposed and worshiped in remembrance of that event.

The town's main square, now known as Piazza della Signoria, was dedicated to Father Marcello Verona of Discalced Carmelites, a native of Retignano killed in Massa in September 1944 by the Nazi forces.

From Retignano eventually you could see the streams of smoke behind the mountains, index of the massacre happened in Sant'Anna and surroundings on 12 August 1944.

After the World Wars

Third Millennium Retignano

Geography

The maximum altitude is approximately 913 meters above sea level, on the tips of Montalto, where there are the remains of an ancient quarry of Ruby Red, a precious and very rare marble present only in a few areas, and places of extraction of bardiglio (a type of marble too).

It enjoys a mild climate thanks to the opening on the sea, although there are heavy snowfalls in winter (2009 and 2012 years are remembered by the inhabitants for the amount of about 30 cm of snow), and, thanks to its location on hills, from Retignano you can see the valley of Stazzema almost completely. You can also see Mount Pania, Corchia, Matanna, Mount Nona, Mount Procinto and all the adjoining mountains. For this reason it was the seat of local people forts which warned the villagers of the imminent dangerous attacks from the enemies on the coast.

Climate (1960-1990)

According to the weather data from 1961 to 1990, Retignano has a warm climate throughout the year, with the lowest temperature of 6.6 °C in January and a peak of about 22.5 °C in July, which is the hottest month of the year. The hottest month ever was July 2005 and recently July 2015 scored high temperatures.

Rainfall is more significant during autumn and the second part of winter, while in summer it reaches a minimum level. Recently, due to global warming, the total amount of rainy days in Retignano has increased.

The church

Some sources date the construction of the Saint Peter's Church in Retignano prior to the eighth century AD. Initially it was a small building with a facade facing the valley. On the left side was an entrance, later walled up, which today can still see some traces. During the 1200 and was extended toward the west. From 1525 to 1530 was enlarged at the rear with the addition of an apse and circular single-light windows. In 1581 the roof, damaged, was repaired and the occasion was seized for restoring the rectory, the floor and the Tomb of the parish priests (1588).

Shortly before the unification of Italy 1861, the church of San Pietro was further 'modernized' by so doing they disappeared in a short time the last elements of considerable historical interest of the side facades. For lack of funds was not even possible to create a design architect Andreotti of Pietrasanta. In 1902 was restored and the vestry were added in the 1950s of the marble staircases and transferred some registers upstairs.

At the beginning of the 3rd millennium, the weather has damaged the single-light windows and interior walls.

The furniture and historical relics

Among the objects of a certain value stands stoup goblet dating from the sixteenth century and attributed to the school Stagio Stagi of Pietrasanta. It was made about a hundred years before the processional cross made entirely of silver.

The Baptistery of Vincent Tedeschi by Seravezza, the baptismal font Sarzanese of John and Rose on the facade are all works dating from around 1562–1563.

Two tabernacles, located in the side altars in the seventeenth century, were designed and built in 1480 by Lawrence Stagi and his pupils, who ultimarono work in early 1500.

Above the tabernacle of the right was a small painting on canvas, dedicated to the Annunciation, and produced by Tommasi in 1734. In 1964 he was crowned with a crown of gold for the narrow escape from war. In 2009 the painting was stolen.

Inside the sacristy are preserved as registers of marriages and baptisms for the dead, some of which date back to the late fifteenth century.

The cemetery

In 1840 was started the project to build a cemetery. The upper floor was added in 1930 and adorned with special chapels and tombs. Fifty years later it was developed an upper floor of the cemetery.

In the initial period of construction, the project for the construction of the cemetery underwent several changes, especially due to the recent victims of epidemics. In the latter case, the entrance to the cemetery is still visible on a plaque which speaks of the epidemic of cholera that struck the country in 1857 and had some cases even in the years to follow, causing serious havoc among the inhabitants. Although the plaque has been partially damaged by weather and half of it has fallen into disrepair due to a failure of the surrounding land, the inscription is still legible.

When this district was invaded by the disease cholera, from September 5 to 15 October 45 corpses were buried in this land which then, as intended by that time all the burial of the dead, was conveniently enclosed by walls in 1857 and reduced to a regular graveyard, being the master Joseph Graziani the only performer of that work. peace to the souls of those who rest here, is the thought of death in the minds of those who still breathe the air of life....

Monument to the Fallen

To the left of the main entrance of the cemetery, there is an area dedicated to the fallen during the great wars of the twentieth century that marked deeply the country. The area consists of a commemorative walkway to the main monument, while around it stand of trees to symbolize the lives of the men started to fight and never returned. The monument, built in the decades to follow, he also wants to be a constant reminder of the atrocities of war, and a warning that similar events do not happen again. On the main facade has been engraved with a dove, symbol of peace, within whose wings are the words of comfort and an invitation to the brotherhood between peoples.

The bell

The bell attached to the church dedicated to St. Peter's was built over the 17 years from 1599 in 1616. The bells that were included (still existing and working), date back to 1510 and another one in 1570–1571, although both were consecrated only in 1843.

On November 26, 1961, a third bell was added, blessed with Bishop Hugh Camozzo, the then Archbishop of Pisa. To follow the Centenarian Celebration for the Unity of Italy, in 1964 Camozzo opened the cabinet, the bells that still syncs.

Marble quarries

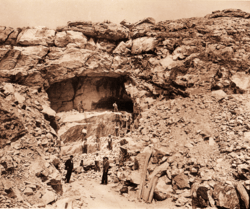

.jpg)

The upper Versilia is characterized by several marble extraction sites. In particular, the gather of quarries located in Retignano, on the mount named Montalto (in English "high mountain"), ar quite well-known. In 1788, following the local decision to "liberalize mining" and with fundings from the Elisian Bank of Elisa Bonaparte Baciocchi, several Italian and foreign entrepreneurs chose to invest in Versilia and aimed to buy lands in the former comunelli of Retignano and Volegno, carrying out the first marble extraction in Versilia during the Industrial Revolution. Among the most important entrepreneurs interested in the quarries of Retignano there are: Sancholle, Beresford and especially Henraux.

Montalto quarries became operative from the biennium 1818-1820, when it was possible to extract and then work a precious kind of marble very appreciated abroad and know, in Italian, as "bardiglio fiorito". The production was remarkable thanks to the high demand for this marble and its quality. However, the miners were forced to work in adverse conditions due to the inaccessible location of the quarries and the difficulty of transporting marble heavy blocks from the quarry site to the collection centers and laboratories, down the valley. Although the production of marble lasted for more than a century and a half, the difficulties were not negligible and, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the quarries risked closure.

During the Second World War and the subsequent Nazi occupation of the municipality of Stazzema, Retignano quarries suspended their mining activities. The greatest entrepreneurs, after World War II, entrusted the quarries to the communities of local quarrymen, preferring to invest in other more profitable sites. In the 1960s, the previous system for extraction (named lizzatura) was abandoned and the marble quarries in Retignano were not given a proper equipment nor roads for vehicles used for the loading/unloading of the material. For this reason, during the Seventies those quarries got abandoned.

Today the caves are freely accessible to everyone and can be reached via the paths in the woods linking the villages or Retignano and Volegno. As already noted, the quarries today are not in business but are rich in almost all medicinal plants typical of the Mediterranean are found in abundance thyme, asparagus, camugero, grape seed and other plants still.

Demographic figures

| Year | Inhabitants |

|---|---|

| 1551 | 213 |

| 1745 | 386 |

| 1835 | 455 |

| 1840 | 519 |

| 1843 | 536 |

| 1845 | 559 |

| 1928 | 800 |

| 1964 | 550 |

| 2000 | less than 400 |

| 2014 | about 350[9] |

As you can see, the number of the inhabitants had rapidly decreased in the last 40 years due to the economical boom in the 1960s, which made most of the people move to the nearby cities, or because of the two worldwide conflicts, which caused a high number of deaths. Also, many Retignano inhabitants moved to the United States or managed to reach South America, especially Argentina.

Third Millennium Retignano

In the village there are two associations that meet citizenship: the centennial of Retignano Mercy, founded in 1908, and C.R.S. (which stands for Circolo Ricreativo Sportivo and can be translated in Sports Recreational Club), founded as C.R. Operaio (C.R. Worker). In 2001 following the merger with Polisportiva Retignano took its current name, its own representative in the football league is a militant FIGC third category, after a season in the second. In all, the country team has won as many as nine tournaments, earning nine stars on the coat (a cat in the foreground on a white-blue).

Local people organize regular village events of a certain social, religious and tourist importance, such as festivals on the occasion of Saint Peter's celebrating day, processions, illuminations of Jesus' Dead, which always attract hundreds of people, small exhibitions, dancing in the streets. The country is home to the Alta Versilia Football Tournament, a challenge involving long formations of the countries of Stazzemese to win the 'Trophy Barsottini', a special cup in honour of a great male player died a long time ago.

On June 29 each year (the feast of the saint patron of the country), the Sagra del Tordello (Tordello Feast) festival begins, usually lasting three or four days. The event is sometimes repeated in mid-July and attracts many people, especially for the quiet, relaxing atmosphere of the mountains at night.

Since 1953 there has been a weather station in the village, which provides statistics for the entire municipality of Stazzema. Even if that meteorological station is not advanced, it keeps providing data to servers just like it has just been installed.

In 2006 an older school building was turned into a restaurant and nearby into the headquarters of CERAFRI, which is a center for the monitoring of the hydrological risk of Versilia arose after the needs that emerged as a result of flood in 1996.

In 2009 the theft of the famous shrine of the Immaculate Conception framework has caused great distress in the country, even the dismay of the priest. During the rule of the Germans in World War II in Versilia, the villagers had turned to that framework Retignano was spared from destruction and displacement. After some hours, some still-unknown soldiers brought the news about the countermand.

In 2013 summer, Retignano held the 1st Trofeo San Pietro, which consists in a competitive race and in a non-competitive one, with special tracks for children. The paths were spread all over the village with different difficulties depending on the type of race choice.

From Retignano it is possible to hike to Mont'Alto and access the "Scalette" (Ladders).

Holy celebration of "Dead Christ"

In Versilia, on the occasion of Good Friday and only every three years, they hold a special ceremony that draws several hundreds of people: the procession of "Dead Christ". Although you do not have very precise dating of the origins of this religious event, due to the poor condition of the parish archives, it is believed that in cities like Forte dei Marmi and Camaiore since the seventeenth century it performed a similar function, after some priests, who met in a council during Holy Week, decided to improve the representation of the passion of Christ.

Enjoying some success and arousing interest in the populations settled in the mountains, this kind of procession was also welcomed by the community of villages like Retignano and Terrinca. Unfortunately, the documents about the beginnings of this celebration are pretty much damaged and no longer readable; sometimes the sources are inaccessible or not available without a special permission. In order to solve the problem, Lorenzo Vannoni, one of the inhabitants of Retignano, asked the elders to talk about the celebrations, sharing their knowledge about it.[10]

Between the 18th and 19th centuries, the retignanesi and people from Terrica gave away to a long series of processions in memory of Jesus, which take place in conjunction with the celebrations in Seravezza. These three villages initially had their own celebrations organised at the same time, then over time people tended to be less involved and therefore, maybe because it was also a more democratic decision, they decide to alternate: each village would have the possibility of organizing the procession only every three years. They were built many Pietà (statues about Mary and Jesus), or works depicting Jesus in various ways.

On Good Friday, Retignano recreates kind of the atmosphere of Jesus's age. During the afternoon, people light glasses containing short candles, along with electrical bulbs spread all over the village to highlight the buildings and the way to the church, where the procession begins and ends. The bell tower is also illuminated by more colorful lights, sometimes even decorated. The whole mountains are sometimes illuminated too.

People walk slowly up and down the hill of Retignano, following the illuminated path. Someone carries the statue of Jesus, while readers quote some Biblic extracts or make the attendants reflect on some topics. The Gospel and the musicians accompany the whole thing, while everyone is asked to hold a candle in their hands.[10]

Trivia

- In 1640 Pope Paul V granted special indulgences to those who recited the fifteen items in the church of the Rosary.

- The church was consecrated in the distant December 29, although the year is not yet clear.

- December 21, 1959 the church of St. Peter's Rectory was elevated to 'Priory' by order of the Archbishop of Pisa.

- The current mayor of Stazzema, Maurizio Verona, comes from Retignano.

See also

- Volegno

- Sant'Anna di Stazzema

- Chapel of Our Lady's Assumption into Heaven

References

- "Retignano". web.tiscali.it. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- "Comitato di Lucca". Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- Lanfranco Sanna. "I LIGURI APUANI storiografia, archeologia, antropologia e linguistica" (PDF). Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Lorenzo Marcuccetti (2007). "I Liguri Apuani: una confederazione di popoli". Abitare la memoria. Turismo in Alta Versilia. Lucca. pp. 39–43.

- Some historical information of the village are written in a shor research made by a priest in the Sixties. Every inhabitant has a copy of that research.

- Ivano Salmoiraghi. "Il borgo di Retignano, Stazzema". www.inversilia.org. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- Ranieri Barbacciani Fedeli e Antonio Cavagna Sangiuliani di Gualdana (1845). Saggio storico, politico, agrario e commerciale dell'antica e moderna Versilia. Retrieved June 24, 2015.

- This figures are written on local records and were published by a Retignano priest in the Sixties

- Supposed to be

- Lorenzo. "La Processione di Gesù Morto". www.retignano.altervista.org. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- This article is a translation of the Italian article with the same name.

Further reading

- Repetti, Emanuele (1843). Dizionario geografico fisico storico della Toscana (in Italian).

- Repetti, Emanuele (1841). Dizionario geografico fisico storico della Toscana contenante la descrizione di tutti i luoghi del granducato, ducato di Lucca, Garfagnana e Lunigiana (in Italian). Coi tipi di A. Tofani.

- Barbacciani Fedeli, Ranieri (1845). Saggio storico dell'antica e moderna Versilia. Tip. Fabris.

- L. Gierut (2001). Monumenti e lapidi in Versilia in memoria dei Caduti di tutte le guerre. Lucca: Associazione Nazionale Famiglie Caduti e Dispersi in guerra.

- A. Forni (1975). Saggio storico dell'antica e moderna Versilia (modern reprint). Bologna. p. 340.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Retignano. |

- (in Italian) Official website

- (in Italian) Torneo Alta Versilia 2015

- (in Italian) Marble quarries, Retignano, Henraux

- (in Italian) Retignano marble quarries

- (in Italian) Dead Jesus holy celebration