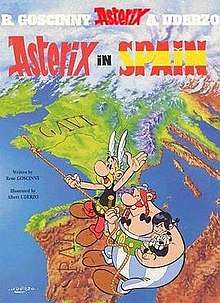

Asterix in Spain

Asterix in Spain (French: Astérix en Hispanie, "Asterix in Hispania") is the fourteenth volume of the Asterix comic book series, by René Goscinny (stories) and Albert Uderzo (illustrations). It was originally serialized in Pilote magazine, issues 498–519, in 1969, and translated into English in 1971.[1]

| Asterix in Spain (Astérix en Hispanie) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date | 1971 |

| Series | Asterix |

| Creative team | |

| Writers | Rene Goscinny |

| Artists | Albert Uderzo |

| Original publication | |

| Date of publication | 1969 |

| Language | French |

| Chronology | |

| Preceded by | Asterix and the Cauldron |

| Followed by | Asterix and the Roman Agent |

Plot summary

Upon learning that a village of Iberian resistance fighters have refused Roman rule, Julius Caesar and his Romans kidnap Chief Huevos Y Bacon's son Pepe and send him to Gaul as a hostage, where Asterix and Obelix defeat Pepe's escort and shelter him in their village. When Pepe's mischief (and his enjoyment of the bard Cacofonix's music and singing) frustrates the Gauls, Asterix and Obelix are assigned to take him home. Accordingly, Asterix, Obelix, Pepe and Dogmatix travel to Iberia, where Spurius Brontosaurus (the leader of Pepe's Roman escort), having seen them surreptitiously, accompanies them in disguise.

When Brontosaurus sees Asterix and Obelix overcome some bandits, he plans to steal the magic potion that increases Asterix's strength; but is caught red-handed by Asterix and in the subsequent chase both are arrested by Roman legionaries. In the circus of Hispalis, they enact the story's 'myth' of bullfighting, wherein Asterix, having seized a red cloak belonging to a high-ranked Roman spectator, is repeatedly charged by an aurochs, which he ultimately tricks into knocking itself senseless. With his victory, Asterix is released and Spurius Brontosaurus, discharged from the army, gladly decides to make his living as a bullfighter.

Obelix has meanwhile brought Pepe back to his village, which is besieged by the Romans. In his eagerness to be re-united with Asterix, Obelix scatters the Roman lines and the commanding officer determines to maintain a stalemate similar to that surrounding Asterix and Obelix's village. The protagonists then say a tearful goodbye to Pepe and the Iberians and return to Gaul for their victory banquet, where Obelix gives a demonstration of Spanish dancing and singing, to the annoyance of blacksmith Fulliautomatix (the latter muttering "A fish, a fish, my kingdom for a fish!") and the delight of Cacofonix.

Notes

- The name of the Iberian chieftain, Huevos Y Bacon, is a play on the traditional Spanish food huevos rancheros.

- The taking of children as hostages was not unknown in ancient times and offered means of maintaining a truce. Hostages were mostly well treated by their takers (even in fiction, Caesar insists that Pepe be treated with the respect due to a chieftain's son). An example is the young Roman Aëtius, given as a hostage to Alaric I the Visigoth. Aëtius thus gained first-hand knowledge of the barbarians' methods of battle. This was to prove invaluable when, in later life, he opposed Attila the Hun.

- Pepe in the beginning confronts Caesar armed with a sling and says "You shall not pass". This is a reference to the ¡No pasarán! speech delivered in Madrid by Dolores Ibárruri Gómez during the Spanish Civil War.

- Various scenes depict stereotypical behaviour associated with Spaniards: their pride, their choleric tempers; and the cliché of roads in disrepair (page 34). On page 38 the generally slow aid for car problems is spoofed too.

- The line "I think he has their ears because he fought so well" on page 1 may be either a reference to the corrida, where a bullfighter receives the ear and tail of a bull for an impressive fight, or to Napoleon's habit of pulling on a favourite soldier's ear as a reward.

- The scenes where various Gauls and Goths (Germans) travel in house-shaped chariots, are a parody on the vacations in Spain in motor homes.

- "Two locals" in Hispania represent Don Quixote and Sancho Panza; this is made clear by their visual appearance and by Quixote's sudden "charge" at the mention of windmills.

- When the frightened Roman Brontosaurus tries to act Spanish, his knees shake against each other, and Pepe says "his knees make a nice accompaniment"; this is a reference to castanets which make a similar sound when used while singing.

- The travelers witness nocturnal processions of druids, a very clear reference to the religious processions associated with later Spanish people; one such procession places the druids in conical masks recalling those of a Spanish priesthood.

- The conductor in the arena, featured on page 44, is a caricature of French conductor Gérard Calvi.

- The final scenes are a fictional depiction of the origin of bull fighting, a tradition in Spain.

- The line "A fish, a fish, my kingdom for a fish" on the last page, is a reference to William Shakespeare's play Richard III, wherein Richard demands a horse in the same words. The line is also referenced with Asterix in Britain's Chief Mykingdomforanos (a dialect form of "My kingdom for a horse").

- Although the Iberian peninsula had long been controlled by Rome, this album mentions the Battle of Munda, which took place in 45 BC (also mentioned), and thus about a year prior to Caesar's assassination; but appears in nearly 20 following albums over a much greater time period.

- This was the first book in the series to feature Unhygienix the fishmonger and his wife Bacteria. It is also the first to feature a fight between the villagers, started by Unhygenix's fish.

- Pepe's skill with the sling may be a historical nod to the ancient slingers of the Balearic Islands, famous for their skill with this weapon. The Carthaginian general Hannibal, and later the Romans, made extensive use of their skill in their armies.

In other languages

- Basque:Asterix Hispanian

- Catalan: Astèrix a Hispània

- Croatian: Asteriks u Hispaniji

- Czech: Asterix v Hispánii

- Dutch: Asterix in Hispania

- Finnish: Asterix Hispaniassa

- Galician: Astérix en Hispania

- German: Asterix in Spanien

- Greek: Ο Αστερίξ στην Ισπανία

- Icelandic: Ástríkur á Spáni

- Indonesian: "Asterix di Spanyol"

- Italian: Asterix in Iberia

- Norwegian: Asterix i Spania

- Polish: Asterix w Hiszpanii

- Portuguese: Astérix na Hispânia

- Russian: Астерикс в Испании

- Slovene:Asterix v Hispánii

- Spanish: Astérix en Hispania

- Swedish: Asterix i Spanien

- Turkish: Asteriks İspanya'da

Reception

On Goodreads, Asterix in Spain has a score of 4.09 out of 5.[2]

References

- "Asterix in Spain (1969) – Read Asterix Comics Online". asterixonline.info. Retrieved 2018-10-03.

- "Asterix in Spain (Asterix, #14)". www.goodreads.com. Retrieved 2018-10-03.