Ramla

Ramla (Hebrew: רַמְלָה, Ramla; Arabic: الرملة, ar-Ramlah), also Ramle, Ramlah,[2] Remle and historically sometimes Rama, is a city in central Israel. The city is predominantly Jewish with a significant Arab minority. Ramla was founded circa 705–715 CE by the Umayyad governor and future caliph Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik. Ramla lies along the route of the Via Maris, connecting old Cairo (Umayyad-period Fustat) with Damascus, at its intersection with the road connecting the port of Jaffa with Jerusalem.[3]

Ramla

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | Ramla |

| • Also spelled | Ramleh (unofficial) |

| |

Emblem of Ramla | |

Ramla Location within Israel  Ramla Ramla (Israel) | |

| Coordinates: 31°56′N 34°52′E | |

| Country | |

| District | Central |

| Founded | c. 705–715 |

| Government | |

| • Type | City |

| • Mayor | Michael Vidal |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,993 dunams (9.993 km2 or 3.858 sq mi) |

| Population (2019)[1] | |

| • Total | 76,246 |

| • Density | 7,600/km2 (20,000/sq mi) |

It was conquered many times in the course of its history, by the Abbasids, the Ikhshidids, the Fatimids, the Seljuqs, the Crusaders, the Mameluks, the Ottoman Turks, the British, and the Israelis. After an outbreak of the Black Death in 1347, which greatly reduced the population, an order of Franciscan monks established a presence in the city. Under Arab and Ottoman rule the city became an important trade center. Napoleon's French Army occupied it in 1799 on its way to Acre.

The town had an Arab majority before most of its Arab inhabitants were expelled or fled during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War.[4] The town was subsequently repopulated by Jewish immigrants. In 2001, 80% of the population were Jewish and 20% Arab (16% Arab Muslims and 4% Arab Christians).

In recent decades, attempts have been made to develop and beautify the city, which has been plagued by neglect, financial problems and a negative public image. New shopping malls and public parks have been built, and a municipal museum opened in 2001.[5]

A 2013 Israeli police report documented that the Central District ranks fourth among Israel's seven districts in terms of drug-related arrests.[6] Today, five prisons are located in Ramla, including the maximum-security Ayalon Prison and Israel's only women's prison called Neve Tirza.[7]

History

Early Muslim period

According to the 9th-century Arab geographer Ya'qubi, ar-Ramleh (Ramla) was founded in 716 by the governor of the Umayyad District of Palestine (Jund Filastin), Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik, brother and successor of Caliph Walid I. Its name was derived from the Arabic word raml (رمل), meaning "sand" or "sandy".[8] The name of La Rambla, a major street of Barcelona, is ultimately derived from the same linguistic origin. The early residents came from nearby Ludd (Lydda, Lod). Ramla flourished as the capital of Jund Filastin, which was one of the five districts of the Syrian province of the Umayyad and Abbasid empires.[9]

Ramla was the principal city and district capital almost until the arrival of the Crusaders in the 11th century.[10] In the 8th century, the Umayyads built the White Mosque, which was hailed as the finest in the land, outside of Jerusalem. The remains of this mosque, dominated by a minaret added at a later date, can still be seen today. In the courtyard are underground water cisterns from this period.[11]

Ramla was sometimes referred to as Filastin, in keeping with the common practice of referring to districts by the name of their main city.[12][13]

The 10th-century geographer al-Muqaddasi ("the Jerusalemite") describes Ramla at the peak of its prosperity:

- "It is a fine city, and well built; its water is good and plentiful; it fruits are abundant. It combines manifold advantages, situated as it is in the midst of beautiful villages and lordly towns, near to holy places and pleasant hamlets. Commerce here is prosperous, and the markets excellent...The bread is of the best and the whitest. The lands are well favoured above all others, and the fruits are the most luscious. This capital stands among fruitful fields, walled towns and serviceable hospices...".[14][15]

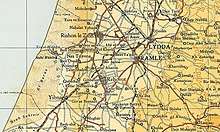

Ramla's economic importance, shared with the neighbouring city of Lydda, was based on its strategic location. Ramla was at the intersection of two major roads, one linking Egypt with Syria (the so-called "Via Maris") and the other linking Jerusalem with the coast.[16]

In 1068 a ground-rupturing earthquake centered in Wadi Arabah left Ramla totally destroyed, killing some 15,000-25,000 inhabitants. The city lay abandoned for four years and never fully recovered it previous status.[17]

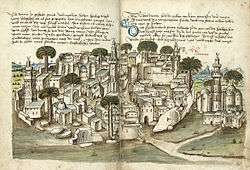

Crusader period

The armies of the First Crusade took the hastily evacuated town without a fight. In the early years of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem though, control over this strategic location led to three consecutive battles between the Crusaders and Egyptian armies from Ascalon. As Crusader rule stabilized, Ramla became the seat of a seigneury in the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Lordship of Ramla within the County of Jaffa and Ascalon. It was a city of some economic significance and an important way station for pilgrims travelling to Jerusalem. The Crusaders identified it with the biblical Ramathaim and called it Arimathea.[18][19]

_-_Geographicus_-_Rama-bruijn-1698.jpg)

Around 1163, rabbi and traveller Benjamin of Tudela, who also mistook it for a more ancient city, visited "Rama, or Ramleh, where there are remains of the walls from the days of our ancestors, for thus it was found written upon the stones. About 300 Jews dwell there. It was formerly a very great city; at a distance of two miles (3 km) there is a large Jewish cemetery."[20]

Ottoman period

In the early days of the Ottoman period, in 1548, a census was taken recording 528 Muslim families and 82 Christian families living in Ramla.[21][22][9]

On March 2, 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte occupied Ramla during his unsuccessful bid to conquer Palestine, using the Franciscan hospice as his headquarters.[23] The village appeared as 'Ramleh' on the map of Pierre Jacotin compiled during this campaign.[24]

In 1838 Edward Robinson found Ramleh to be a town of about 3000 inhabitants, surrounded by olive-groves and vegetables. It had few streets, and the houses were made of stone and were well-built. There were several mosques in the town.[25]

In 1863 Victor Guérin noted that the Latin (Catholic) population was reduced to two priests and 50 parishioners.[26] In 1869, the population was given as 3,460; 3000 Muslims, 400 Greek Orthodox and 60 Catholics.[27]

In 1882, the Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine noted that there was a bazaar in the town, "but its prosperity has much decayed, and many of the houses are falling into ruins, including the Serai."[28] Expansion began only at the end of the 19th century.[29]

In 1889, 31 Jewish worker families settled in the town, which had no Jewish population at the time.[30]

British Mandate period

In the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, 'Ramleh' had a population of 7,312 inhabitants; 5,837 Muslims, 1,440 Christians and 35 Jews.[31] The Christians were further noted by denomination: 1,226 Orthodox, 2 Syrian Orthodox (Jacobites), 150 Roman Catholics, 8 Melchites, 4 Maronite, 15 Armenian, 2 Abyssinian Church and 36 Anglicans.[32]

Less than a decade later, the population had increased nearly 25%; the 1931 census recorded 10,347 people, of whom there were 8,157 Muslims, 5 Jews, 2,194 Christians and 2 Druze, in a total of 2,339 houses.[33]

Ramla was connected to wired electricity (supplied by the Zionist-owned Palestine Electric Company) towards the end of the 1920s. Economist Basim Faris noted this fact as proof of Ramla's higher standard of living than neighbouring Lydda. In Ramla, he wrote, "economic demands triumph over nationalism" while Lydda, "which is ten minutes' walk from Ramleh, is still averse to such a convenience as electric current, and so is not as yet served; perhaps the low standard of living of the poor population prevents the use of the service at the present rates, which cannot compete with petroleum for lighting".[34]

Sheikh Mustafa Khairi was mayor of Ramla from 1920 to 1947.[35]

The 1945/46 survey gives 'Ramle' a population of 15,160, of whom 11,900 were Muslim and 3,260 Christian.[36]

1947-48 war

Ramla was part of the territory allotted to a proposed Arab state under the 1947 UN Partition Plan.[37] However, Ramla's geographic location and its strategic position on the main supply route to Jerusalem made it a point of contention during the 1947–1948 civil war, followed by the internationalised 1948 Arab–Israeli War. A bomb by the Jewish militia group Irgun went off in the Ramla market on February 18, killing 7 residents and injuring 45.[38][39] After a number of unsuccessful raids on Ramla, the Israeli army launched Operation Dani. Ramla was captured on 12 July 1948, a few days after the capture of Lydda. The Arab resistance surrendered on July 12,[40] and most of the remaining inhabitants were driven out on the orders of David Ben-Gurion.[41] A disputed claim, advanced by scholars including Ilan Pappé, characterizes this as ethnic cleansing.[42] After the Israeli capture, some 1,000 Arabs remained in Ramla; more were transferred to the town by the IDF from outlying Arab settlements which the military wanted emptied. As of 2000, the total population of Arab refugees and their descendants with origins in Ramla was estimated by Benny Morris and other historians at 635,000.

State of Israel

Ramla became a mixed Jewish-Arab town within the state of Israel. Arab homes of those who left in Ramla were given by the Israeli government to Jewish immigrants arriving at this time. In February 1949, the Jewish population was over 6,000. Ramla remained economically depressed over the next two decades, although the population steadily mounted, reaching 34,000 by 1972.[43]

In 2015, Ramla had one of Israel's highest crime rates.[44]

Earthquakes

The city suffered severe damage from earthquakes in 1033, 1068, 1070, 1546, and 1927.[45]

Landmarks and notable buildings

White Tower

The Tower of Ramla, also known as the White Tower, was built in the 13th century. It served as the minaret of the White Mosque(al-Masjid al-Abyad) erected by Caliph Suleiman in the 8th century, of which only remnants remain today.[46] The tower is six stories high, with a spiral staircase of 119 steps.[47]

Pool of Arches

The Pool of Arches, also known as St. Helen's Pool and Bīr al-Anezīya, is an underground water cistern built during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Haroun al-Rashid in 789 CE (in the Early Muslim period) to provide Ramla with a steady supply of water.[48] Use of the cistern was apparently discontinued at the beginning of the tenth century (the beginning of the Fatimid period), possibly due to the fact that the main aqueduct to the city went out of use at that time.[49]

Franciscan church and hospice

The Hospice of St. Nicodemus and St. Joseph of Arimathea on Ramla's main boulevard, Herzl Street, is easily recognized by its clock-faced, square tower. It belongs to the Franciscan church. Napoleon used the hospice as his headquarters during his Palestine campaign in 1799.

Ramla Museum

The Ramla Museum is housed in the former municipal headquarters of the British Mandatory authorities. The building, from 1922, incorporates elements of Arab architecture such as arched windows and patterned tiled floors. After 1948, it was the central district office of the Israeli Ministry of Finance. In 2001, the building became a museum documenting the history of Ramla.

Other

The Commonwealth War Cemetery is the largest of its kind in Israel, holding graves of soldiers fallen during both World Wars and the British Mandate period.

The Giv'on immigration detention centre is also located in Ramla.

Archaeology

Identification

A tradition reported by Ishtori Haparchi (1280–1355) and other early Jewish writers is that Ramla was the biblical Gath of the Philistines.[50][51] Initial archaeological claims seemed to indicate that Ramla was not built on the site of an ancient city,[52] although in recent years the ruins of an old city were uncovered on the southern outskirts of Ramla.[53] Earlier, Benjamin Mazar had proposed that ancient Gath lay at the site of Ras Abu Hamid east of Ramla.[54] Avi-Yonah, however, considered that to be a different Gath, usually now called Gath-Gittaim.[55] This view is also supported by other scholars, those holding that there was, both, a Gath (believed to be Tell es-Safi) and Gath-rimmon or Gittaim (in or near Ramla).[56][57]

Excavation history

Archaeological excavations in Ramla conducted in 1992–1995 unearthed the remains of a dyeing industry (Dar al-Sabbaghin, House of the Dyers) near the White Mosque; hydraulic installations such as pools, subterranean reservoirs and cisterns; and abundant ceramic finds that include glass, coins and jar handles stamped with Arabic inscriptions.[58] Excavations in Ramla continued as late as 2010, led by Eli Haddad, Orit Segal, Vered Eshed, and Ron Toueg, on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA).[59]

Cave with rare ecosystem

In May 2006, a naturally sealed-off underground space now known as Ayyalon Cave was discovered near Ramla, outside Moshav Yad Rambam. The cave sustains an unusual type of ecosystem, based on bacteria that create all the energy they need chemically, from the sulfur compounds they find in the water, with no light or organic food coming in from the surface. A bulldozer working in the Nesher cement quarry on the outskirts of Ramla accidentally broke into the cavern. The finds have been attributed to the cave's isolation, which led to the evolution of a whole food chain of specially developed organisms, including several previously unknown species of invertebrates. With several large halls on different levels, it measures 2,700 metres (8,900 ft) long, making it the third-largest limestone cave in Israel.[60]

One of the finds was an eyeless scorpion, given the name Akrav israchanani honouring the researchers who identified it, Israel Naaman and Hanan Dimentman. All ten specimen of the blind scorpion found in the cave had been dead for several years, possibly because recent overpumping of the groundwater has led the underground lake to shrink, and with it the food supply to dwindle. Seven more species of troglobite crustaceans and springtails were discovered in "Noah's Ark Cave", as the cave has been dubbed by journalists, several of them unknown to science.[61]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1945 | 15,300 | — |

| 1972 | 34,000 | +3.00% |

| 2001 | 62,000 | +2.09% |

| 2004 | 63,462 | +0.78% |

| 2009 | 65,800 | +0.73% |

| 2014 | 72,293 | +1.90% |

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), a total of 63,462 people were living in Ramla at the end of 2004. In 2001, the ethnic makeup of the city was 80% Jewish, 20% Arab (16% Muslim Arabs and 4% Christian Arabs).[62] Ramla is the center of Karaite Judaism in Israel.[63]

Most Jews from Karachi, Pakistan, have immigranted to Israel and have resettled in Ramle, where they have built a synagogue named Magen Shalome, after the Magain Shalome Synagogue from Karachi.[64]

Economy

According to CBS data, there were 21,000 salaried workers and 1,700 self-employed persons in Ramla in 2000. The mean monthly wage for a salaried worker was NIS 4,300, with a real increase of 4.4% over the course of 2000. Salaried males had a mean monthly wage of NIS 5,200, with a real increase of 3.3%, compared to NIS 3,300 for women, with a real increase of 6.3%. The average income for self-employed persons was NIS 4,900. A total of 1,100 persons received unemployment benefits, and 5,600 received income supplements.

Nesher Israel Cement Enterprises, Israel's sole producer of cement, maintains its flagship factory in Ramla.[65]

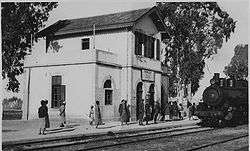

Transportation

Ramla Railway Station provides an hourly service on the Israel Railways Tel Aviv–Jerusalem line. The station is located in north east side of the city and originally opened in April 1891, making it the oldest active railway station in Israel.[66] It was most recently reopened on April 12, 2003 after having been rebuilt in a new location closer to the town's center.

Education

According to CBS, there are 31 schools and 12,000 students in the city. These include 22 elementary schools with a student population of 7,700 and nine high schools with a population of 3,800. In 2001, 47% of Ramla's 12th grade students graduated with a bagrut matriculation certificate. Many of the Jewish schools are run by Jewish orthodox organisations.

The Arabs, both Muslims and Christian, increasingly depend on their own private schools and not Israeli governmental schools. There are currently two Christian schools, such as Terra Santa School, the Greek Orthodox School, and there is one Islamic school in preparations.

The Owpen House in Ramla is a preschool and daycare center for Arab and Jewish children. In the afternoons, Open House runs extracurricular coexistence programs for Jewish, Christian, and Muslim children.[67]

Notable people

Alphabetical list by surname where extant. Traditional, pre-modern Arab names by ism (given name).

- Elias Abuelazam (born 1976), serial killer

- Ron Atias (born 1995), taekwondo athlete who represented Israel at the 2016 Summer Olympics

- Orna Barbivai (born 1962), army general and politician

- Yaqub al-Ghusayn (1899–1948), Arab nationalist leader of the Youth Congress Party

- Amir Hadad (born 1978), tennis player[68]

- Barno Itzhakova (1927–2001), Tajik vocalist, immigrated to Ramla in 1991

- Khayr al-Din al-Ramli, 17th-century Islamic legal scholar

- Moni Moshonov (born 1976), actor and comedian

- Yishai Oliel (born 2000), tennis player

- Khalil al-Wazir a.k.a. Abu Jihad (1935–1988), Palestinian Arab co-founder of the Fatah organization

Twin towns—sister cities

Ramla is twinned with:

See also

References

- "Population in the Localities 2019" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- King, Edmund (2004) "Stephen (c.1092–1154)" Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, online edition accessed Oct 27, 2009

- University of Haifa Excavation in Marcus Street, Ramala; Reports and studies of the Recanati Institute for Maritime Studies and Excavations, Haifa 2007

- Pilger, 2011, p. 194

- "עיריית רמלה – אתר האינטרנט". Ramla.muni.il. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "Zachary J. Foster, "Are Lod and Ramla the Drug Capitals of Israel and Palestine?," Palestine Square Blog December 30, 2015". Archived from the original on December 30, 2015.

- "There's only one women's prison in Israel — and a photographer documented the inmates in harrowing detail". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- Palmer, 1881, p. 217

- Petersen, 2005, p. 95

- Le Strange, 1890, p?

- Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla"; Myriam Rosen-Ayalon, The first century of Ramla, Arabica, vol 43, 1996, pp250–263.

- Rabbi Ashtory HaParchi (lived in Palestine ca. 1310–1355), in his travel book Kaftor VaPerach twice mentions this practice; also a 1326 report in The Travels of Ibn Battuta, ed. H.A.R. Gibb (Cambridge University Press, 1954), 1:71–82. For the earlier period: Amikam Elad, Two identical inscriptions from Jund Filastin from the reign of the 'Abbasid Caliph, Al-Muqtadir, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, vol. 35 (1992) pp301–360.

- Foster, Zachary J. (2016). "Was Jerusalem Part of Palestine? The Forgotten City of Ramla, 900–1900". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. doi:10.1080/13530194.2016.1142426.

- Mukaddasi , 1886, p. 32

- Le Strange, 1890, p. 304

- Le Strange, 1890, p? ; Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2016-03-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Encyclopedia of Islam, article "al-Ramla".

- Pringle, 1998, p. 181

- Marcus Nathan Adler (1907). The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 26–27. Adler notes that earlier translations wrote "3" rather than "300", but he considers that incorrect.

- Cohen and Lewis, 1978, pp. 135-144

- From the sources listed above: no Jews in 1525, 1538, 1548, 1592; two in 1852

- "INS Scholarship 1998: Jaffa, 1799". Napoleon-series.org. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- Karmon, 1960, p. 171

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol 3, pp. 25-33

- Guérin, 1868, pp. 34-55

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 252

- Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 253

- Yehoshua Ben-Arieh, "The Population of the Large Towns in Palestine During the First Eighty Years of the Nineteenth Century, According to Western Sources", in Studies on Palestine during the Ottoman Period, ed. Moshe Ma'oz (Jerusalem, 1975), 49–69.

- HaMelitz newspaper, 26/11/1889 page 2, National Library of Israel

- Barron, 1923, Table VII, Sub-district of Ramleh, p. 21

- Barron, 1923, Table XIV, p. 21

- Mills, 1932, p. 22

- Faris, A. Basim (1936) Electric Power in Syria and Palestine. Beirut: American University of Beirut Press, pp. 66-67. Also see: Shamir, Ronen (2013) Current Flow: The Electrification of Palestine. Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 71, 74

- "Sheikh Mustafa Yousef Ahmad Abdelrazzaq El-Khairi (El-Khayri) The Mayor of Ramla (1920–1947)". Palestineremembered.com. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 30

- UN map Archived 2009-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Embassy of Israel, London, website. 2002. Quoting Zeez Vilani – 'Ramla past and present'.

- Scotsman February 24, 1948: 'Jerusalem (Monday) – The 'High Command' of the Arab military organisation issued a communiqué to the newspapers here to-day claiming full responsibility for the explosion in Ben Yehuda Street on Sunday. It was said to be in reprisal for an attack by Irgun at Ramleh several days ago.'

- Morris, 2004, p. 427

- Many of the refugees including a large number of children died (at least 400+ according to the Arab historian 'Aref al-Aref) from thirst, hunger, and heat exhaustion after being stripped of their valuables on the way out by Israeli soldiers. Morris, "Operation Dani and the Palestinian Exodus from Lydda and Ramle in 1948", The Middle East Journal, 40 (1986) 82–109; Morris, 2004, pp. 429–430, who quotes the orders; The Rabin Memoirs (censored section, The New York Times, October 23, 1979).

- For the use of the term "ethnic cleansing", see, for example, Pappé 2006.

- On whether what occurred in Lydda and Ramle constituted ethnic cleansing:

- Morris 2008, p. 408: "although an atmosphere of what would later be called ethnic cleansing prevailed during critical months, transfer never became a general or declared Zionist policy. Thus, by war's end, even though much of the country had been 'cleansed' of Arabs, other parts of the country—notably central Galilee—were left with substantial Muslim Arab populations, and towns in the heart of the Jewish coastal strip, Haifa and Jaffa, were left with an Arab minority."

- Spangler 2015, p. 156: "During the Nakba, the 1947 [sic] displacement of Palestinians, Rabin had been second in command over Operation Dani, the ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian towns of towns of Lydda and Ramle."

- Schwartzwald 2012, p. 63: "The facts do not bear out this contention [of ethnic cleansing]. To be sure, some refugees were forced to flee: fifty thousand were expelled from the strategically located towns of Lydda and Ramle ... But these were the exceptions, not the rule, and ethnic cleansing had nothing to do with it."

- Golani and Manna 2011, p. 107: "The explusion of some 50,000 Palestinians from their homes ... was one of the most visible atrocities stemming from Israel's policy of ethnic cleansing."

- A. Golan, Lydda and Ramle: "From Palestinian-Arab to Israeli Towns", 1948–1967, Middle Eastern Studies 39,4 (2003) 121–139.

- "Police study: Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Haifa, Ramle and Eilat Israel's most violent cities". Ha'aretz. October 9, 2011. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- D. H. K. Amiran (1996). "Location Index for Earthquakes in Israel since 100 B.C.E.". Israel Exploration Journal. 46 (1/2): 120–130.

- "Israel Antiquities Authority – Gallery of Sites and Finds". Antiquities.org.il. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- The Guide to Israel, Zeev Vilnai, Hamakor Press, Jerusalem, 1972, p. 208.

- "Ramla Pool of Arches". Iaa-conservation.org.il. 2005-12-27. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- Toueg, Ron, Ramla, Pool of the Arches: Final Report (09/07/2020), Hadashot Arkheologiyot, Volume 132, Year 2020, Israel Antiquities Authority. Accessed 27 July 2020.

- Ishtori Haparchi, Kaphtor u'ferach, vol. II, chapter 11, s.v. ויבנה בארץ פלשתים, (3rd edition) Jerusalem 2007, p. 78 (Hebrew)

- B. Mazar (1954). "Gath and Gittaim". Israel Exploration Journal. 4 (3/4): 227–235.

- Nimrod Luz (1997). "The Construction of an Islamic City in Palestine. The Case of Umayyad al-Ramla". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Third Series. 7 (1): 27–54.

- Ramla: Excavations and Surveys in Israel (2009)

- Mazar (Maisler), Benjamin (1954). "Gath and Gittaim". Israel Exploration Journal. 4 (3): 233. JSTOR 27924579.

- Michael Avi-Yonah. "Gath". Encyclopedia Judaica. 7 (second ed.). p. 395.

- Rainey, Anson (1998). "Review by: Anson F. Rainey". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 118 (1): 73. JSTOR 606301.

- Rainey, Anson (1975). "The Identification of Philistine Gath". Eretz-Israel: Archaeological, Historical and Geographical Studies. Nelson Glueck Memorial Volume: 63–76. JSTOR 23619091.

- "Vincenz : Ramla | The Shelby White – Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications". Fas.harvard.edu. Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2010, Survey Permit # A-5947, Survey Permit # A-6029, Survey Permit # A-6052, and Survey Permit # A-6057

- "Underground world found at quarry – Israel Culture, Ynetnews". Ynetnews.com. June 20, 1995. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "One year later, 'Noah's Ark' cave is no longer a safe haven". Haaretz. 19 July 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- "Ramla, Israel". Kansas City Sister Cities.

- "Karaite Center". Ramla Tourism Site. Archived from the original on 2015-02-07.

- Pakistan Jewish Virtual History Tour, Jewish Virtual Library

- "Nesher Israel Cement Enterprises Ltd". Nesher.co.il. Archived from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-04.

- Jaffa Station History, retrieved November 6, 2009

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2007-09-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Tennis – 2002 – WIMBLEDON – July 1 – Aisam-Ul-Haq Qureshi". ASAP Sports. July 1, 2002. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

Bibliography

- Barron, J. B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Cohen, Amnon; Lewis, B. (1978). Population and Revenue in the Towns of Palestine in the Sixteenth Century. ISBN 0783793227.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H. H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Guérin, V. (1868). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 1: Judee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Centre.

- Karmon, Y. (1960). "An Analysis of Jacotin's Map of Palestine" (PDF). Israel Exploration Journal. 10 (3, 4): 155–173, 244–253.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Mukaddasi (1886). Description of Syria, including Palestine. London: Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Palmer, E. H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Petersen, Andrew (2005). The Towns of Palestine Under Muslim Rule. British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 1841718211.

- Pococke, R. (1745). A description of the East, and some other countries. 2. London: Printed for the author, by W. Bowyer. (Pococke, 1745, vol 2, p. 4; cited in Robinson and Smith, vol. 3, 1841, p. 233)

- Pilger, J. (2011). Freedom Next Time. Random House. ISBN 1407083864.

- Pringle, Denys (1998). The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem: L-Z (excluding Tyre). II. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0 521 39037 0.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Strange, le, G. (1890). Palestine Under the Moslems: A Description of Syria and the Holy Land from A.D. 650 to 1500. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ramla. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ramla. |

- Official site (in Hebrew)

- "A Dangerous Tour at Ramle", by Eitan Bronstein

- Portal Ramla

- Israel Service Corps: Ramla Community Involvement

- The Tower of Ramla, 1877

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 13: IAA, Wikimedia commons