Rambynas

Rambynas is a hill on the right bank of the Neman River in Rambynas Regional Park, Pagėgiai Municipality, western Lithuania. The current hill, about 46 metres (151 ft) above sea level and about 40 metres (130 ft) above the Neman, is a remnant of the larger hill that was destroyed by erosion. The hill was known as sacred among locals and played a role in the ceremonies of pagan Lithuanians. It is featured in many local legends and is protected by the state as a mythological object. A large stone at the top of the hill, known as the altar stone, was destroyed by a miller in 1811. Rambynas became popular with Prussian Lithuanians at the end of the 19th century who organized various events, most notably celebrations of the Saint Jonas' Festivals or Rasos (summer solstice), on the hill. They rebuilt the altar in 1928. The hill is popular with Lithuanian neo-pagans and hosts the annual celebrations of the summer solstice on 23 June.

Geography

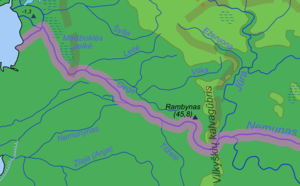

The hill is located between the villages of Bitėnai and Bardinai on the right bank of the Neman River. The nearest towns are Pagėgiai and Vilkyškiai. The river serves as the border between Lithuania and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia. Rambynas is located about 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) north of Neman (previously Ragnit, Ragainė) and east of Sovetsk (previously Tilsit, Tilžė).[1]

Geographically, it is part of the 35-kilometre (22 mi) long moraine ridge known as Vilkyškiai ridge formed during the last glacial period.[2] A large landslide 400 metres (1,300 ft) in length and 27 metres (89 ft) in width occurred on 12 September 1835. Smaller landslides occurred on 21 July 1878 (about 115 metres (377 ft) in length) and in summer 1926.[3][4] Today, only its northern slope survives. The remaining hill measures 270 metres (890 ft) in length and up to 60 metres (200 ft) in width.[5] It rises about 46 metres (151 ft) above sea level and about 40 metres (130 ft) above the Neman.[1]

History

Early history

The hill and the surrounding area was long inhabited as evidenced by two socketed axes from the Bronze Age (1100–850 BC) found on Rambynas.[6] Historians believe that the hill was the location of Ramigė, a fort of the Skalvians, one of the Baltic tribes.[7] In 1275, the fort was attacked and destroyed by the Teutonic Order. The vogt of Sambia first attacked Ragnit (Neman), then crossed the river, and captured Ramigė. That signified Teutonic conquest of Skalvia.[7] However, an exploratory excavation of about 150-square-metre (1,600 sq ft) area in 2002 by Valdemaras Šimėnas found no significant cultural layer.[8]

The name Rambynas (as Rambyn) was mentioned in 1385 and 1394 in the Die Littauischen Wegeberichte, a report of military routes into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania prepared by the Teutonic Order. The report also mentioned a sacred forest to the east of the hill.[1] The 1422 Treaty of Melno established the border between Teutonic Order and Lithuania. The hill remained on the Teutonic side, later part of Prussia inhabited by a large Lithuanian-speaking minority (Prussian Lithuanians).

While the region officially converted to Christianity, old pagan beliefs persisted. In 1595, cartographer Caspar Hennenberger published an explanation to his map of Prussia. He mentioned that Rambynas was considered a sacred place and that women had to be clean and well dressed if they wanted to climb the hill or they would become ill.[1] Georg Christoph Pisanski wrote in 1769 that locals performed pagan rituals on the hill despite prohibitions from the Christian priests. In 1867, Otto Glagau, a journalist from Berlin, visited Rambynas and wrote that newlyweds would climb the hill and would leave small sacrifices. The most extensive description of the hill and its legends was provided by Eduard Gisevius, a Lithuanian-language teacher in Tilsit.[1] In 1838, he published Scenes from Lithuanian People's Lives (Szenen aus dem Volksleben der Litauer).[9] He also described a 600-year-old three-trunk linden tree that grew near the hill and was worshiped as goddess of fate Laima's tree.[10]

Resurgence

.jpg)

Gisevius' stories popularized Rambynas among Prussian Lithuanians.[1] In 1881[11] or 1884,[3] Vidūnas began organizing Saint Jonas' Festival (also known as Rasos) on the hill. However, it was a private property and thus it was difficult to host larger and more frequent events. Therefore, Birutė Society purchased a plot of land in 1896 and the same year organized a larger festival on the hill. However, Birutė lacked financial strength to pay the purchase price and the plot was transferred to Wilhelm Gaigalat.[1] Two other plots were owned by the Garden Beautification Society in Tilsit and by the Tilsit Landkreis. In 1910, Prussian Lithuanians established a society that collected money to buy the entire hill and charged 10 pfennigs for the admission to the hill. There were plans to build a monument to poet Kristijonas Donelaitis on Rambynas, but they were not realized due to World War I.[1]

After the Klaipėda Revolt in 1923, Klaipėda Region (including Rambynas) became part of Lithuania. The hill became a frequently visited location and developed into a kind of resort. The nearby village of Bitėnai had three restaurants.[12] Celebrations of the Saint Jonas' Festivals became grand affairs attended by many dignitaries. For example, in 1929, the celebrations were attended by a delegation from the League of Nations; its head even swore an improvised oath in the name of pagan thunder god Perkūnas.[13] In 1928, Martynas Jankus built an altar and started keeping a guestbook, which is known as the Eternal Book of Rambynas.[1] After World War II, authorities of the Lithuanian SSR allowed to resume the celebration of the Saint Jonas' Festivals in 1957.[3] They even built a cement stage for events (it was demolished in 2010).[8] German writer Johannes Bobrowski described old time celebrations on Rambynas in his 1966 novel Litauische Claviere.

Protected area

The first preserves in Lithuania were established in September 1960. Among the 89 preserves established on that date, there was a landscape preserve of Rambynas covering 2,798 hectares (6,910 acres).[11] In September 1992, Lithuania established 30 regional parks, including the Rambynas Regional Park with initial area of 4,520 hectares (11,200 acres). The landscape preserve was reduced to 396 hectares (980 acres) and became an integral part of the park. However, the directory of the park was established only in 2001.[11] The same year, Rambynas (area of 5.65 hectares (14.0 acres)) was added to the cultural object registry as a mythological object.[5] The new directory with funding from Phare strengthened the eroded slopes, installed paths and staircases for visitors, conducted environmental and archaeological research. In 2007–2013, the park built further paths, viewing platforms, information stands, etc. A barn of a pre-war restaurant, owned by Gustavas Volbergas, was reconstructed into a visitor center.[11]

Altar

At the top of the hill, there was a large stone known as the altar stone. It was first mentioned by Georg Christoph Pisanski in 1769.[14] According to an 1867 description by Otto Glagau, the stone had a flat top and measured about 15 cubits (approximately 10 metres (33 ft)) in diameter. The taller side measured 2.8 metres (9 ft 2 in) and the lower 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in).[14] According to Eduard Gisevius, the stone had carvings of a sword, human hand and feet, animal footprints, and something that resembled a Greek temple.[3] This information is dubious as Gisevius wrote many years after the destruction of the stone and no other account mentioned the markings.[1]

The stone was broken up in 1811 by a German miller named Schwartz from the Bardehnen (Bardinai) village to make a millstone. As he could not find local help, he had to hire three German workers from Tilsit (Sovetsk).[1] According to local legends, the workers were injured and the miller soon died. The circumstances of his demise vary: he lost his mill in a storm in 1818 and died in an accident working in another mill;[14] he lost his business and became an alcoholic;[15] he was found crushed and strangled by the millstone.[1]

In 1928, to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the Act of Independence of Lithuania, Martynas Jankus and Juozas Adomaitis[16] decided to build the altar on Rambynas and carve Columns of Gediminas into the top stone.[14] In 1939, Klaipėda Region was annexed by Nazi Germany and the altar was demolished. The altar, designed to burn fire, was re-built during the Soviet era (exact circumstances are not known). In 2010–2011, Pagėgiai Municipality cleaned up Rambynas' territory, strengthened the eroded slopes, and improved the sightseeing platform.[16] At the same time, the altar was demolished and replaced by an abstract sculptural composition by sculptor Regimantas Midvikis. It is meant to symbolize the Prussian trinity – Potrimpo, Perkūnas, and Peckols – and includes a small metal altar for sacred fire.[17]

Eternal Book

In 1928, for the 10th anniversary of the Act of Independence of Lithuania, Martynas Jankus decided to create a guestbook for those who visited Rambynas. Signing in the book became an integral part of the tradition during the interwar celebrations of Saint Jonas' Festival.[18] The book, known as the Eternal Book of Rambynas, is one of the largest in Lithuania. It measures 61.5 by 44 centimetres (24.2 in × 17.3 in) and is 10 centimetres (3.9 in) thick. It weighs 18.5 kilograms (41 lb) and is accompanied by a wooden case that weights another 10 kilograms (22 lb).[18] The covers are wood upholstered with leather and metal corners and close with two buckles. The second page is a portrait of Grand Duke Vytautas by Adomas Varnas.[18] The first comment was left by Vydūnas.[19] The visitors left notes and comments in Lithuanian, Latvian, Estonian, Russian, German, Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, Japanese, Hindi.[18] The Japanese comments were left by Yotaro Sugimura, Assistant Secretary-General of the League of Nations.[13]

The last entry was made on 16 March 1939, four days before the German ultimatum to Lithuania.[18] Jankus took the book to Kaunas where it was kept by polkovnik Juozas Šarauskas. In 1963, it was transferred to the Martynas Mažvydas National Library of Lithuania where is it kept in the rare manuscript section.[19] In 2002, a copy was made by Dalia Marija Šaulauskaitė and is kept at the Martynas Jankus Museum in Bitėnai. Museum visitors are free to sign in the book. The copy has 1,000 pages and at 22.5 kilograms (50 lb) is heavier than the original.[19]

Legends

Lithuanian mythology

The sacred hill is surrounded by many legends and stories. According to one of them, the altar stone was put on Rambynas by thunder god Perkūnas who also buried a treasure of gold and silver harrow under the stone. Perkūnas then chose the hill and his home.[1] Another story has it that the altar stone was brought by giant Rambynas, one of three sons of Nemunas, who offered it as a sacrifice to Perkūnas. The hill became a temple attended by priests (krivis) and priestess (vaidilutė). They were driven away by the Teutonic Order, but laumės cursed the stone – while the stone stood, good fortune would bless the region; if the stone was damaged, bad fortunes would follow.[1]

Napoleon's treasure

There are many local stories and legends about a treasure supposedly buried on or near Rambynas by the retreating French Grande Armée after the unsuccessful invasion of Russia in 1812. The X Corps commanded by General Jacques MacDonald retreated from Riga via Tilsit where he spent five days.[20] Stories circulated that in 1920, when Klaipėda Region was administered as a mandate of the League of Nations by the French, a group of Frenchmen dug up some boxes at a local cemetery. In 1930, a detailed map was purportedly discovered that showed where the treasure was buried.[21] This inspired several expeditions in the 1930s in attempts of finding it.[22] Another attempt was organized in summer 1974 by Soviet authorities. According to various stories, it was a direct order from Moscow.[21] The area of excavations was guarded by Soviet troops and involved two visitors from East Germany.[23] In July 2003, Lithuanian newspapers published a story that a treasure was found near Rambynas, but it was quickly debunked as an embellishment of a previous April Fools' Day joke.[24] The various attempts at finding the treasure damaged the hill, local cemeteries, and several other local archaeological and cultural objects.[25]

References

- Žemaitaitis, Algirdas (2009). "Rambynas". Mažosios Lietuvos enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). 4. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. pp. 37, 40. ISBN 5-420-01470-X.

- Česnulevičius, Algimantas (2015-01-21). "Vilkỹškių kalvãgūbris". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Kviklys, Bronius (1968). Mūsų Lietuva (in Lithuanian). IV. Boston: Lietuvių enciklopedijos leidykla. pp. 715–716. OCLC 3303503.

- Anulienė, Audronė (2009). "Rambyno kalno slėpiniai" (PDF). Samogitia (in Lithuanian). 2: 11. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Rambyno kalnas". Kultūros vertybių registras (in Lithuanian). Kultūros paveldo departamentas. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Grigalavičienė, Elena (1974). "Žalvario amžiaus paminklai ir radiniai" (PDF). In Rimantienė, Rimutė (ed.). Lietuvos TSR archeologijos atlasas (in Lithuanian). 1. Vilnius: Mintis. pp. 211, 218.

- Žemaitaitis, Algirdas (2009). "Ramigė". Mažosios Lietuvos enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). 4. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. pp. 40–41. ISBN 5-420-01470-X.

- Fediajevas, Olegas; Kvedaravičius, Mantas (2010). "Rambyno kalno (11219), Pagėgių sav., 2010 m. archeologinių žvalgymų ataskaita" (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: VšĮ „Kultūros paveldo išsaugojimo pajėgos“. pp. 3–5. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Kšanienė, Daiva; Milius, Vacys; Reisgys, Jurgis; Sliužinskas, Rimantas (2000). "Gisevius, Eduardas". Mažosios Lietuvos enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). I. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 495. ISBN 5-420-01471-8.

- Bacevičius, Egidijus (10 November 2009). "Krašto praeitį liudija vardiniai medžiai ir želdiniai". Šilainės sodas (in Lithuanian). 21 (93). ISSN 2029-6282. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Milašauskienė, Diana (2015). "Rambyno kraštovaizdžio draustiniui - 55". Rambynas (in Lithuanian). 8. ISSN 2029-0756. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Valstybinės saugomų teritorijų tarnyba (10 October 2010). "Duris atveria nauji lankytojų centrai" (in Lithuanian). Bernardinai.lt. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Žalys, Vytautas (2012). Lietuvos diplomatijos istorija 1925–1940 metais (PDF) (in Lithuanian). II, part I. Edukologija. pp. 170–171. ISBN 978-9955-20-801-3.

- Užpelkienė, Dalia, ed. (2000), "Aukuro akmuo" (PDF), Šilutės kraštas: enciklopedinis žodynas (in Lithuanian), Šilutė: Prūsija, p. 15, ISBN 9986-798-05-1

- Skipitis, Eugenijus (2015-10-31). "Tylus gyvenimas šimtmečių pakelėje". Tauragės kurjeris (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Balsys, Liutauras (1 July 2011). "Rambyne sunaikintas aukuras, tarnavęs šventai atgimimo Ugniai" (in Lithuanian). Baltų žinyčios vartai. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Razutienė, Loreta (2011-06-22). "Mintys apie Aukurą ant Rambyno kalno" (in Lithuanian). Pagėgiai Municipality. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- Gocentas, Vytautas (2000). "Amžinoji Rambyno kalno knyga". Mažosios Lietuvos enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). I. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 55. ISBN 5-420-01471-8.

- "Į Seimą atvežta sunkiausia Lietuvos knyga". Šilainės sodas (in Lithuanian). 1 (49). 15 January 2008. ISSN 2029-6282. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- MacDonald, Étienne Jacques Joseph Alexandre (1892). Rousset, Camille (ed.). Recollections of Marshal Macdonald, Duke of Tarentum. 1. Translated by Stephen Louis Simeon. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 61.

- "Ieškojo kruvinojo Napoleono lobio: dar yra viena vieta, kur gali slypėti atsakymas". Istorijos detektyvai (in Lithuanian). Delfi.lt. 14 August 2016. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Užpelkienė, Dalia, ed. (2000), "Rambyno kalnas" (PDF), Šilutės kraštas: enciklopedinis žodynas (in Lithuanian), Šilutė: Prūsija, p. 171, ISBN 9986-798-05-1

- Gudavičiūtė, Dalia (2012-12-09). "Napoleono lobiu tikėjo net sovietų valdžia" (in Lithuanian). Lrytas.lt. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Šilinienė, Vilija (2003-07-22). "Pranešimas apie Napoleono lobį - dienraščio paleista antis" (in Lithuanian). Vakarų ekspresas. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- "Išleistas penktasis žurnalo "Rambynas" numeris" (in Lithuanian). Alkas.lt via Voruta. 2012-11-12. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rambynas. |

- Virtual tour of historical and cultural heritage objects of the Rambynas Regional Park

- Rombinus in the Geographical Dictionary of the Kingdom of Poland, volume IX (Poźajście — Ruksze) 1888, S. 734. (in Polish)