Rail transport in Europe

Rail transport in Europe is characterised by its diversity, both technical and infrastructural.

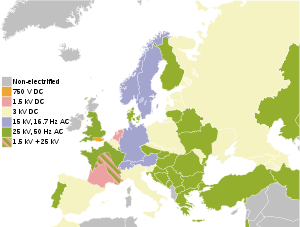

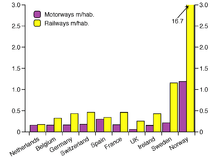

Rail networks in Western and Central Europe are often well maintained and well developed, whilst Eastern, Northern and Southern Europe often have less coverage and/or infrastructure problems. Electrified railway networks operate at a plethora of different voltages AC and DC varying from 750 to 25,000 volts, and signalling systems vary from country to country, hindering cross-border traffic.

The European Union aims to make cross-border operations easier as well as to introduce competition to national rail networks. EU member states were able to separate the provision of transport services and the management of the infrastructure by the Single European Railway Directive 2012. Usually, national railway companies were split to separate divisions or independent companies for infrastructure, passenger and freight operations. The passenger operations may be further divided to long-distance and regional services, because regional services often operate under public service obligations (which subsidise unprofitable but socially desirable routes), while long-distance services usually operate without subsidies.

Differences between countries

The 2017 European Railway Performance Index ranked the performance of national rail systems as follows:[2]

- Tier One: Switzerland, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Austria, Sweden, and France.

- Tier Two: Great Britain, the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Spain, the Czech Republic, Norway, Belgium, and Italy.

- Tier Three: Lithuania, Slovenia, Ireland, Hungary, Latvia, Slovakia, Poland, Portugal, Romania, and Bulgaria.

Rail gauge

While most railways in Europe use 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge—in some other countries, like on the Iberian Peninsula, or countries which territories used to be a part of Russian Empire and Soviet Union: widespread broad gauge exists. For instance Eastern European countries like Russia, Ukraine, Armenia, Moldova, Belarus, Finland, and the Baltic states (Estonia, Latvia, LIthuania) use a gauge width of 1,520 mm (4 ft 11 27⁄32 in) or 1,524 mm (5 ft) (also known as Russian gauge). In Spain and Portugal 1,668 mm (5 ft 5 21⁄32 in) (also known as Iberian gauge) is used. The reason for different track gauges between countries was mainly because of the idea of preventing trains from an invading country running on "your" track, but historically competition between railroads and perceived benefits of certain gauges also played a role in divergent standards. Ireland uses the somewhat unusual 5 ft 3 in (1,600 mm) gauge, referred to in Ireland as "Irish Gauge" (but is an island with no external cross-border links).

Electrification

Likewise, electrification of lines varies between countries. 15 kV AC has been used in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Norway and Sweden since 1912, while the Netherlands uses 1500 V DC, France uses 1500 V DC and 25 kV AC, and Belgium uses 3 kV DC. All this makes the construction of truly pan-European vehicles a challenging task and, until recent developments in locomotive construction, was mostly ruled out as being impractical and too expensive.

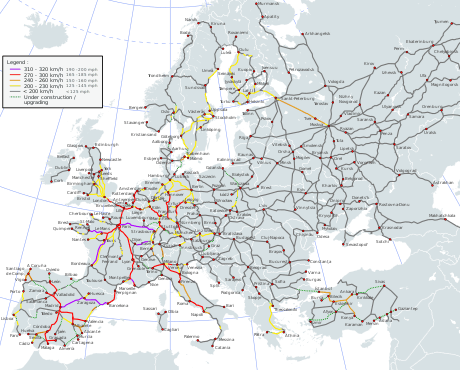

The development of an integrated European high-speed rail network is overcoming some of these differences. All high-speed lines outside of Russia, including those built in Spain and Portugal, use 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge tracks. Likewise all European high-speed lines, outside of Germany, Austria and Italy use 25 kV AC electrification (Electrification of high-speed rail in Italy is mixed 3 kV DC and 25 kV AC). This means that by 2020 high-speed trains can travel from Italy to the United Kingdom, or Portugal to the Netherlands without the need for multi-voltage systems or breaks of gauge.

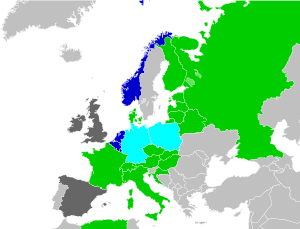

Signalling

Multiple incompatible signalling systems are another barrier to interoperability. The EU countries have 19 different signalling systems. A unified signalling system, ETCS is the EU's project to unify signalling across Europe. The specification was written in 1996 in response to EU Directive 96/48/EC. ETCS is developed as part of the European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS) initiative, and is being tested by multiple Railway companies since 1999. All new high-speed lines and freight main lines funded partially by the EU are required to use level 1 or level 2 ETCS signalling.

Loading gauge

The loading gauge on the main lines of Great Britain, almost all of which were built before 1900, is generally smaller than in mainland Europe, where the slightly larger Berne gauge (Gabarit passe-partout international, PPI) was agreed to in 1913 and came into force in 1914.[3][4] As a result, British (passenger) trains have noticeably and considerably smaller loading gauges and smaller interiors, despite the track being standard gauge.

This results in increased costs for purchasing trains as they must be specifically designed for the British network, rather than being purchased "off-the-shelf". For example, the new trains for HS2 have a 50% premium applied to the "classic compatible" sets which will be able to run on the rest of the network, meaning they will cost £40 million each rather than £27 million for the captive stock (built to European standards and unable to run on other lines), despite the captive stock being larger.[5]

Railway platform height

The European Union Commission issued a TSI (Technical Specifications for Interoperability) that sets out standard platform heights for passenger steps on high-speed rail. These standard heights are 550 and 760 mm (21.7 and 29.9 in).

Cross-border operation

The main international trains operating in Europe are:

- Enterprise (Republic of Ireland & Northern Ireland (UK))

- Eurostar (United Kingdom, France, Belgium, Netherlands)

- EuroCity/EuroNight (conventional trains operated by nearly all Western and Central European operators, with the notable exception of the UK and Ireland)

- Intercity Direct (Netherlands, Belgium)

- InterCityExpress (Germany, Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Switzerland, Austria)

- TGV (France, Belgium, Italy, Switzerland, Spain, Germany, Luxembourg)

- Thalys (France, Germany, Belgium, Netherlands)

- Railjet (Austria, Germany, Switzerland, Hungary, Czechia, Italy, Slovakia)

- Elipsos (France, Spain)

- Trenhotel (France, Spain, Portugal)

- Oresundtrain (Denmark, Sweden)

- SJ 2000 (Sweden, Norway, Denmark)

- NSB (Sweden, Norway)

- Allegro (Finland, Russia)

- Belgrade-Bar Railway (Serbia, Montenegro)

Additionally, there are a lot of cross-border trains at the local level. Some local lines, like the Gronau to Enschede line between Germany and the Netherlands, operate on the signalling system of the country the line originates from, with no connection to the other country's network, whilst other train services like the Saarbahn between Germany and France use specially equipped vehicles that have a certificate to run on both networks. When there is an electrification difference between two countries, border stations with switchable overhead lines are used. Venlo railway station in the Netherlands is one such example, the overhead on the tracks can be switched between the Dutch 1500 V DC and the German 15 kV AC, which means a change of traction (or reconfiguring a multiple-voltage vehicle) is necessary at the station.

Subsidies

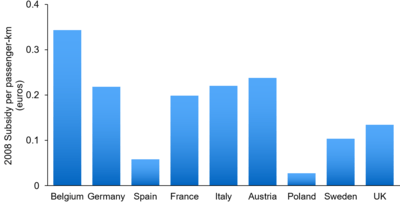

EU rail subsidies amounted to €73 billion in 2005.[7] Subsidies vary widely from country to country in both size and how they are distributed, with some countries giving direct grants to the infrastructure provider and some giving subsidies to train operating companies, often through public service obligations. In general long-distance trains are not subsidised.

The 2017 European Railway Performance Index found a positive correlation between public cost and a given railway system’s performance and differences in the value that countries receive in return for their public cost. The 2017 and 2015 performance reports found a strong relationship between cost efficiency and the share of subsidies allocated to infrastructure managers. A transparent subsidy structure, in which public subsidies are provided directly to the infrastructure manager rather than spread among multiple train-operating companies, correlates with a higher-performing railway system.[2]

The 2017 Index found Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland capture relatively high value for their money, while Luxembourg, Belgium, Latvia, Slovakia, Portugal, Romania, and Bulgaria underperform relative to the average ratio of performance to cost among European countries.[2]

Total railway subsidies by country

| Country | Subsidy in billions of Euros | Year |

|---|---|---|

| 17.0 | 2014[8] | |

| 13.2 | 2013[9] | |

| 7.6 | 2012[10] | |

| 5.1 | 2015[11] | |

| 4.4 | 2016[12] | |

| 4.3 | 2012[13] | |

| 2.8 | 2012[14] | |

| 2.5 | 2014[15] | |

| 2.3 | 2009[16] | |

| 1.7 | 2008[17] | |

| 1.6 | 2009[18] | |

| 1.4 | 2008[17] | |

| 0.91 | 2008[17] |

Harmonising rules

- First Railway Package (EU Directive 91/440)

- Second Railway Package

- Third railway package

- Fourth railway package

- European Rail Traffic Management System on harmonised signalling systems, to allow more cross-border trains

- Trans-European conventional rail network

- Single European Railway Area

See also

External links

- Council Directive 91/440/EEC of 29 July 1991 on the development of the Community's railways

- Council Directive 96/48/EC of 23 July 1996 on the interoperability of the trans-European high-speed rail system

- Maps of railway networks in Europe

- Level of service on passenger railway connections between European metropolises Report of the Transport and Spatial Planning Institute

- Eurail map

- halotravel.com organization that advises and supplies Eurail or Interrail travelers with information, travel routes and passes.

References

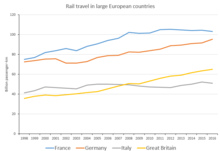

- "OECD Passenger transport".

- "the 2017 European Railway Performance Index". Boston Consulting Group.

- Berne loading gauge

- A Word on Loading Gauges.

- "HS2 Cost and Risk Model Report" (PDF). p. 15.

- "European rail study" (PDF). pp. 6, 44, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-03.

2008 data is not provided for Italy, so 2007 data is used instead

- "EU Technical Report 2007".

- "German Railway Financing" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-10.

- "Efficiency indicators of Railways in France" (PDF).

- "Public Expenditure on Railways in Europe: a cross-country comparison" (PDF). p. 10.

- "Spanish railways battle profit loss with more investment". 17 September 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2016.

- "GB rail industry financial information 2015-16" (PDF). Retrieved 9 March 2017.

£3.2 billion, using average of £1=1.366 euros for 2015-16

- "Kosten und Finanzierung des Verkehrs Strasse und Schiene 2012" (PDF) (in German). Neuchâtel, Switzerland: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 10 December 2015. pp. 6, 9, 11. Retrieved 2015-12-20.

4.7 billion Swiss francs

- "Implementation of EU legislation on rail liberalisation in Belgium, France, Germany and The Netherlands" (PDF).

- "ProRail report 2015" (PDF). p. 30.

- "ANNEX to Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation (EC) No 1370/2007 concerning the opening of the market for domestic passenger transport services by rail" (PDF) (COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT: IMPACT ASSESSMENT). Brussels: European Commission. 2013. pp. 6, 44, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-03.

2008 data is not provided for Italy, so 2007 data is used instead

- "European rail study report" (PDF). pp. 44, 45. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-03.

Includes both "Railway subsidies" and "Public Service Obligations".

- "The evolution of public funding to the rail sector in 5 European countries - a comparison" (PDF). p. 6.