RSPB Dearne Valley Old Moor

RSPB Dearne Valley Old Moor is an 89-hectare (220-acre) wetlands nature reserve in the Dearne Valley near Barnsley, South Yorkshire, run by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB). It lies on the junction of the A633 and A6195 roads and is bordered by the Trans Pennine Trail long-distance path. Following the end of coal mining locally, the Dearne Valley had become a derelict post-industrial area, and the removal of soil to cover an adjacent polluted site enabled the creation of the wetlands at Old Moor.

| RSPB Dearne Valley Old Moor | |

|---|---|

View across a lake | |

Old Moor reserve shown within South Yorkshire | |

| Location | South Yorkshire, England |

| Coordinates | 53°30′55″N 1°21′53″W |

| Area | 89 ha |

| Average elevation | 29 m |

| Established | 1998 |

| Operator | Royal Society for the Protection of Birds |

| Website | RSPB page |

Old Moor is managed to benefit bitterns, breeding waders such as lapwings, redshanks and avocets, and wintering golden plovers. A calling male little bittern was present in the summers of 2015 and 2016. Passerine birds include a small colony of tree sparrows and good numbers of willow tits, thriving here despite a steep decline elsewhere in the UK.

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council created the reserve, which opened in 1998, but the RSPB took over management of the site in 2003 and developed it further, with funding from several sources including the National Lottery Heritage Fund. The reserve, along with others nearby, forms part of a landscape-scale project to create wildlife habitat in the Dearne Valley. It is an 'Urban Gateway' site with facilities intended to attract visitors, particularly families. In 2018, the reserve had about 100,000 visits. The reserve may benefit in the future from new habitat creation beyond the reserve and improved accessibility, although there is also a potential threat to the reserve from climate change and flooding.

Landscape

Most of the Dearne Valley area lies on the coal measures, comprising Carboniferous sandstone and slate with seams of coal. The valleys contain fertile alluvium deposited by their rivers, and the sandstone forms rolling ridges cut by the broad floodplains.[1]

The area has been settled continuously since prehistoric times, with villages developing on the drier sandstone ridges above the flood plain from at least the late Saxon period.[2][3] Mining is recorded from at least the 13th century, and probably back to Roman Britain,[4] and the area became heavily industrialised in the 18th century with the arrival of the Dearne and Dove Canal. This connected Barnsley to the River Don and beyond, aiding the intensive exploitation of the locality's coal, sandstone and iron ore. Over the next two centuries, especially following the arrival of the railway in 1840, the area became dominated by its heavy industries.[2][3]

The name Old Moor may derive from an archaic meaning of moor, referring to a marshy area that was more difficult to cultivate than the alluvium of the flood plain.[5][6] It had been enclosed as a 103 hectares (250 acres) farm by 1757, when it was owned by the Marquess of Rockingham.[6]

History

The Dearne Valley was formerly a major coal mining area, with several accessible seams of high-quality coal, and in 1950s more than 32,000 colliers worked in its 30 pits. The coal industry dominated the area, and its waste rendered the River Dearne lifeless, although a few isolated wetland areas remained, monitored by local birdwatchers.[7]

The miners' strike of 1984 was the first sign of a national programme of pit closures in the UK that led to all the Dearne Valley mines being closed by 1993, with the loss of 11,000 jobs in the industry. About 600 hectares (1,500 acres) of the former Wath Manvers Colliery, including a coking plant and marshalling yard, was left as the largest derelict site in western Europe. The ground was heavily polluted and needed to be restored by covering it with clean soil deep enough for trees and scrubs to become established. To achieve this, 700,000 tonnes (690,000 long tons) of material was removed from the adjacent Old Moor, thereby creating a new wetland at that site.[7]

The Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) were originally intended to run the proposed reserve, and planned a large lake for wintering wildfowl. The Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB) suggested adding reed beds to help the then-struggling bittern population;[4][7] only 11 males were present in the UK at one point in the 1990s.[8] The WWT was at that time also working on its London Wetland Centre, and pulled out of the Old Moor project since it lacked the resources to cope with two large projects.[7]

The creation of the reserve fell to Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council, which offered the site to the RSPB in 1997. At that time, the bird charity was more interested in preserving established habitats than creating new sites, and declined to take on Old Moor. The reserve eventually opened in 1998 as part of the regeneration of the Dearne Valley,[7] and was then developed further with the help of a lottery grant of nearly £800,000 in 2002.[9]

By 2000, the reserve had only 10,000 visitors annually, and was making a financial loss before being taken over by the RSPB in 2003. The RSPB had changed it its position since its refusal in 1997, with a greater emphasis nationally on engaging the public, and more opportunities to work with the Environment Agency to create and manage new wetlands. With help from the Environment Agency, local councils and others, the RSPB tripled its land holding in the area to 309 hectares (760 acres) in the next ten years, while other conservation bodies also created and improved reserves.[7]

Cooperation between conservation organisations and other agencies led to the formation of the Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership (DVLP) in 2014.[7] This is the main coordinating body for the partners in the Dearne Valley scheme,[10] which include the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), local councils, Natural England, The Environment Agency, the Forestry Commission, Yorkshire Water, the RSPB and several local conservation charities.[11] The DVLP is supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund and its administration is the responsibility of Barnsley Council's Museums and Heritage Service. The partnership's remit includes industrial heritage sites as well as the local environment, and its funding for 2014–2019 was £2.4 million, of which £1.8 million was from the National Lottery.[12]

Access and facilities

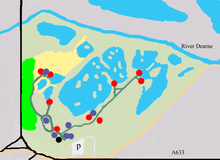

family and photographic activities

visitor centre

water

reed beds

meadow

grass and other vegetation

Old Moor lies about 6.5 kilometres (4.0 mi) from the M1 motorway, and is accessed from Manvers Way (A633) just east of the A6195 Dearne Valley Parkway junction.[13] The nearest railway stations are at Wombwell and Swinton, both about 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) away. Buses are infrequent, but cyclists can access Old Moor by a bridge to the reserve car park from the Trans Pennine Trail long-distance path, which runs along the southern edge of the reserve.[14]

The reserve has a visitor centre, created by Barnsley Council from existing farm buildings,[7] which includes a shop, educational facilities, a café and toilets, picnic and play areas and nature trails. The visitor centre and its café are open daily from 9.30 am–5.00 pm, except for 25 and 26 December, the reserve having the same hours in winter but staying open until 8 pm from April to October. Entrance is free for RSPB members, although there are entry charges for other visitors.[14]

Old Moor was planned as an "Urban Gateway" RSPB site, its playground, café balcony and children's discovery zone intended to attract visitors. It has nine bird hides and viewing screens, and a sunken hide with a reflection pool for the benefit of photographers.[15] The track to the reed bed is 500 metres (550 yd) long and the main track is 500 metres (550 yd).[16] As of 2018, the 89-hectare (220-acre) reserve had about 100,000 visits per year,[7] with around 3,500 children annually making use of the RSPB's on-site education programmes.[15]

The site uses wood pellets and chippings to fuel a 100 kW biomass converter which provides hot water and heating for five buildings on the site.[17]

Management

The main focus on management throughout the Dearne Valley complex is on its key habitats: wet grassland, open water and reed bed. Although the first reeds were planted at Old Moor in 1996, their establishment has been slow because the topsoil had been stripped off leaving only hard sterile clay subsoil for planting. Bringing fertile mud from Blacktoft Sands RSPB reserve has helped, although the reeds still stand in ribbons rather than solid blocks. The reed beds are cut when mature to encourage new growth, and are divided into four sections which can be separately drained.[7]

Wet grassland is kept short for breeding waders through grazing by cattle or Konik horses, and by mowing. Ditches are cleared in rotation, and islands are flooded in winter, if possible, to suppress vegetation. Surviving plants are then cut down, and the soil is rotavated to break up the hard clay and deter invasive New Zealand pygmyweed. As a man-made site, Old Moor has a complex water-management system that allows water levels to be controlled in separate compartments of the wetland. In general, water levels are kept high in winter, then lowered to expose the islands for breeding and passage waders.[7][18]

The Dearne Valley is one of 12 Nature Improvement Areas (NIAs) created as part of the UK Government's response to Sir John Lawton's 2010 report "Making Space for Nature", which proposed managing conservation on a landscape scale.[19][20] Plans to manage the Dearne Valley on a landscape-wide basis involve coordination with other wetland reserves. Five smaller sites are already managed by the RSPB; these are Bolton Ings and Gypsy Marsh close to Old Moor, and Adwick Washlands, Wombwell Ings[14] and Eddersthorpe Flash within a few miles. Other reserves are the Garganey Trust's Broomhill Flash and the Yorkshire Wildlife Trust's (YWT) Denaby Ings. The YWT also manages Barnsley council-owned Carlton Marsh, and the Environment Agency is restoring marshes at Houghton Washland. Other parcels of land are being acquired by the various conservation charities as they become available.[7] The Dearne Valley reserves have no statutory protection, but as of 2019, the process to become a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) is under way.[7]

Fauna and flora

Birds

Since the 1990s the RSPB has been attempting to create improved habitats for the formerly endangered UK bittern population, with major reed bed creation at their Ham Wall and Lakenheath Fen reserves being a key part of the bittern recovery programme initiated in 1994 as part of the United Kingdom Biodiversity Action Plan.[21] At Old Moor, in addition to the creation of new reed beds, 23,000 small fish were introduced between 2010 and 2016, mainly of species such as rudd and eels that are preferred as food by bitterns. This project increased the fish biomass more than twenty-fold to 11.5 kilograms per hectare (10.3 lb/acre).[7]

Breeding waders include lapwings, redshanks, snipe and avocets, the last species having bred on the reserve since 2011. Predation of wader chicks by foxes has been a problem, so deep ditches and electric fences are being introduced to exclude mammals. Black-headed gull numbers have increased from 183 breeding pairs in 2006 to 2,385 pairs in 2017, and have been joined by Mediterranean gulls, eight being present in 2018. Old Moor is an important wintering site for golden plovers, although numbers have dropped from 6,000–8,000 to 2,000–3,000 in about twenty years.[7]

Passerine birds include a small colony of tree sparrows, currently stable at about ten pairs, and good numbers of willow tits. Willow tits are in steep decline in the UK, disappearing completely from many areas, but numbers are increasing in the Dearne Valley, particularly at Old Moor, where a breeding density of 6.7 territories per square km (17.4 territories per square mile) was the highest in the locality. The post-industrial landscaping and planting in the area have created a suitable habitat for the species containing willow, alder and clumps of bramble close to water and linked by linear features such as railways, canals and streams.[7][22] Cetti's warbler and bearded tit have recently colonised the reserve, and up to three pairs of barn owls breed there.[14]

A calling male little bittern summered in 2015 and 2016, and appeared for a few days in 2017.[7] Other recent rarities include a Baird's sandpiper in 2016,[23] a thrush nightingale and gull-billed tern in 2015,[24] and a black stork in 2014.[25]

Other animals and plants

Lesser noctule bats and water voles figure among the scarcer mammals found on the reserve, and otters have returned to the now-clean rivers.[7] Other mammal species targeted for monitoring during the creation process include the brown hare and the pipistrelle.[4]

The alder leaf beetle, formerly believed extinct in the UK, has colonised the Dearne and other local river catchments, probably introduced when the pollution-tolerant Italian alder was planted on restored land. Other uncommon insects found at Old Moor include the great silver water beetle, the longhorn beetle Pyrrhidium sanguineum, the dingy skipper butterfly, and a day-flying moth, the six-belted clearwing. Nationally scarce nocturnal moths include the cream-bordered green pea and chocolate-tip, while the red-eyed damselfly and red-veined and black darters are notable among the Odonata.[7]

Several rare flies have been recorded, including three species, Parochthiphila coronata, Calamoncosis aspistylina and Neoascia interrupta, otherwise known in the UK only from a few sites in the East Anglian fenland.[26] An unusual plant gall found on creeping bent was caused by the nematode Subanguina graminophila.[27]

Scarce plants include yellow vetchling and hairy bird's-foot trefoil. Marsh orchids flower in grassy areas in the summer,[14] and the same species, along with the bee orchid, has colonised the verges of the adjacent Manvers Way. Other scarce plants found in the area include hairlike pondweed, pond water-crowfoot and greater pond sedge.[7]

Threats and opportunities

The Dearne Valley is a natural washland with a capacity of 4 million cubic metres (5.2 million cu yd), and as such it can normally absorb overflow from its river. The floods of 2007 overwhelmed the storage capacity and covered the whole of Old Moor to hide-roof level, only the visitor centre being untouched.[7] In the longer term, the reserve might be adversely affected by climate change, perhaps leading to alterations in the populations of woodland species.[28]

More positive effects may arise as the local environment improves, with habitat creation occurring beyond the reserve and better accessibility.[29][30] A survey by the DVLP showed that 44% of respondents said that they liked to visit the local wildlife reserves, with another 17% mentioning waterways and lakes. When asked what they liked about the Dearne Valley area, 35% of replies said nature and wildlife.[31]

The success of Old Moor has led to the creation of similar RSPB reserves close to urban areas at Rainham Marshes east of London, Newport Wetlands in South Wales, and RSPB Saltholme on Teesside.[7]

References

- "Earth and Industrial Heritage". Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "The Development of the Dearne". Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Archaeology". Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Ling et al (2003) pp. 30–33.

- "Moor". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Hey (2015) pp. 75–77.

- Capper, Matthew (2019). "Great bird reserves: RSPB Old Moor and the Dearne Valley". British Birds. 112 (2): 70–89.

- Hughes, Steve (2018). "Great bird reserves: Ham Wall". British Birds. 111 (4): 211–225.

- Smith, Kevin (21 June 2002). "HLF pledges massive award for Wetland Centre". Barnsley Metropolitan Council. Archived from the original on 17 December 2004. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- King (2014) p. 1.

- "Dearne Valley Green Heart". RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "About the DVLP". Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- "Finding your way around OldMoor" (PDF). RSPB. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- "RSPB Dearne Valley Old Moor". RSPB. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- King (2014) p. 9.

- "Access Statement for RSPB Old Moor" (PDF). RSPB. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- "Biomass". Alternative Technology Centre. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Bridge, T (2005). "Controlling New Zealand pygmyweed Crassula helmsii using hot foam, herbicide and by burying at Old Moor RSPB Reserve, South Yorkshire, England". Conservation Evidence. 2: 33–34.

- "Making Space for Nature: A review of England's Wildlife Sites and Ecological Network" (PDF). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). 2010. pp. 66–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2013.

- Nature Improvement Areas 2012–15 (Report). DEFRA. 2015. pp. 4–7, 10.

- Brown, Andy; Gilbert, Gillian; Wotton, Simon (2012). "Bitterns and Bittern Conservation in the UK". British Birds. 105 (2): 58–87.

- Carr, Geoff; Lunn, Jeff (2017). "Thriving Willow Tits in a post-industrial landscape". British Birds. 110 (4): 233–240.

- Holt, Chas and the Rarities Committee (2017). "Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2016". British Birds. 110 (10): 562–631.

- Hudson, Nigel and the Rarities Committee (2016). "Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2015". British Birds. 109 (10): 559–642.

- Hudson, Nigel and the Rarities Committee (2015). "Report on rare birds in Great Britain in 2014". British Birds. 108 (10): 565–633.

- Coldwell, John D (2013). "Three fenland flies (Diptera: Chloropidae, Ephydridae and Pipunculidae) found in South Yorkshire". Dipterists Digest. 20 (1): 13.

- Higginbottom, Tom (2013). "Andricus gemmeus– a new gall for Yorkshire" (PDF). The Naturalist. 138 (1082): 17–18.

- King (2014) p. 15.

- King (2014) pp. 61–62.

- King (2014) pp. 141–143.

- King (2014) p. 65.

Cited texts

- Hey, David (2015). A History of the South Yorkshire Countryside. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-3435-4.

- King, Richard (2014). Landscape Conservation Action Plan (PDF). Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership.

- Ling, C.; Handley, J.; Rodwell, J. (2003). "Multifunctionality and scale in post-industrial land regeneration". In Moore, Heather M; Fox, Howard R; Elliott, Scott (eds.). Land Reclamation – Extending Boundaries: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference, Runcorn, UK, 13–16 May 2003. CRC Press. pp. 27–34. ISBN 978-90-5809-562-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Old Moor Wetland Centre RSPB reserve. |

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_717866.jpg)