North American A-5 Vigilante

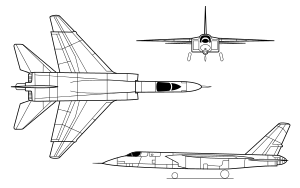

The North American A-5 Vigilante was an American carrier-based supersonic bomber designed and built by North American Aviation for the United States Navy. It set several world records, including long-distance speed and altitude records. Prior to 1962 unification of Navy and Air Force designations, it was designated the A3J Vigilante.[1]

| A-5 (A3J) Vigilante | |

|---|---|

| |

| A3J-1 147858 with NASA as 858, at NASA Dryden in support of the supersonic transport program. | |

| Role | Nuclear strike bomber or reconnaissance aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| First flight | 31 August 1958 |

| Introduction | June 1961 |

| Retired | 20 November 1979 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | United States Navy |

| Produced | 1956–1963 1968–1970 |

| Number built | 167 (137 built as or converted to RA-5C) |

The aircraft briefly replaced the Douglas A-3 Skywarrior as the Navy's primary nuclear-strike aircraft, but its RA-5C tactical strike reconnaissance variant saw extensive service during the Vietnam War.

Design and development

In 1953, North American Aviation began a private study for a carrier-based, long-range, all-weather strike bomber, capable of delivering nuclear weapons at supersonic speeds.[2] This proposal, the North American General Purpose Attack Weapon (NAGPAW) concept, was accepted by the United States Navy, with some revisions, in 1955.[3] A contract was awarded on 29 August 1956. Its first flight occurred two years later on 31 August 1958 in Columbus, Ohio.[4]

At the time of its introduction, the Vigilante was one of the largest and by far the most complex aircraft to operate from a Navy aircraft carrier. It had a high-mounted swept wing with a boundary-layer control system (blown flaps) to improve low-speed lift.[4] It had no ailerons; roll control was provided by spoilers in conjunction with differential deflection of the all-moving tail surfaces. The use of aluminum-lithium alloy for wing skins and titanium for critical structures was also unusual. The A-5 had two widely spaced General Electric J79 turbojet engines, fed by inlets with variable intake ramps, and a single large all-moving vertical stabilizer.[2] Preliminary design studies had employed twin vertical fin/rudders.[4] The wings, vertical stabilizer and the nose radome folded for carrier stowage. The Vigilante had a crew of two seated in tandem, a pilot and a bombardier-navigator (BN) (reconnaissance/attack navigator (RAN) on later reconnaissance versions) seated on North American HS-1A ejection seats.[1][5]

Designated by the US Navy as a "heavy", the A-5 was surprisingly agile; without the drag of bombs or missiles, even escorting fighters found that the clean airframe and powerful engines made the Vigilante very fast at high and low altitudes. However, its high approach speed and high angle of attack contributed to a high workload during carrier landings.[6]

The Vigilante had advanced and complex electronics when it first entered service. It had one of the first "fly-by-wire" systems on an operational aircraft (with mechanical/hydraulic backup) and a computerized AN/ASB-12 nav/attack system incorporating a head-up display ("Pilot's Projected Display Indicator" (PPDI), one of the first), multi-mode radar, radar-equipped inertial navigation system (REINS, based on technologies developed for North American's Navaho missile), closed-circuit television camera under the nose, and an early digital computer known as "Versatile Digital Analyzer" (VERDAN) to run it all.

Given its original design as a carrier-based, supersonic, nuclear heavy attack aircraft, the Vigilante's main armament was carried in an unusual "linear bomb bay" between the engines in the rear fuselage, which allowed the bomb to be dropped at supersonic speeds. The single nuclear weapon, commonly the Mk 28 bomb, was attached to two disposable fuel tanks in the cylindrical bay in an assembly known as the "stores train". A set of extendable fins was attached to the aft end of the most rearward fuel tank. These fuel tanks were to be emptied during the flight to the target and then jettisoned with the bomb by an explosive drogue gun. The stores train was propelled rearward at about 50 feet (15 m) per second (30 knots) relative to the aircraft. It then followed a ballistic path.[7]

In practice, the system was not reliable and no live weapons were ever carried in the linear bomb bay. In the RA-5C configuration, the bay was used solely for fuel. On three occasions, the shock of the catapult launch caused the fuel cans to eject onto the deck; this resulted in one aircraft loss.[8]

The Vigilante originally had two wing pylons, intended primarily for drop tanks. The second Vigilante variant, the A3J-2 (A-5B), incorporated internal tanks for an additional 460 gallons of fuel (which added a pronounced dorsal "hump") along with two additional wing hardpoints, for a total of four. In practice the hardpoints were rarely used. Other improvements included blown flaps on the leading edge of the wing and stronger landing gear.

The reconnaissance version of the Vigilante, the RA-5C, had slightly greater wing area and added a long canoe-shaped fairing under the fuselage for a multi-sensor reconnaissance pack. This added an APD-7 side-looking airborne radar (SLAR), AAS-21 infrared line scanner, and camera packs, as well as improved electronic countermeasures. An AN/ALQ-61 electronic intelligence system could also be carried. The RA-5C retained the AN/ASB-12 bombing system, and could, in theory, carry weapons, although it never did in service. Later-build RA-5Cs had more powerful J79-10 engines with afterburning thrust of 17,900 lbf (80 kN). The reconnaissance Vigilante weighed almost five tons more than the strike version with almost the same thrust and an only modestly enlarged wing. These changes reduced its acceleration and climb rate, though it remained fast in level flight.

The Royal Australian Air Force considered the RA-5C Vigilante as a replacement for its English Electric Canberra. The McDonnell F-4C/RF-4C, Dassault Mirage IVA, and the similar BAC TSR-2 was also considered. However, the TFX (later the F-111C Aardvark) was accepted.[9][10]

Operational history

Designated A3J-1, the Vigilante first entered squadron service with Heavy Attack Squadron THREE (VAH-3) in June 1961 at Naval Air Station Sanford, Florida, replacing the Douglas A-3 Skywarrior in the heavy attack, e.g., "strategic nuclear strike" role.[11] All variants of the Vigilante were built at North American Aviation's facility at Port Columbus Airport in Columbus, Ohio, alongside the North American T-2 Buckeye, T-39 Sabreliner and OV-10 Bronco.

Under the Tri-Services Designation plan implemented under Robert McNamara in September 1962, the Vigilante was redesignated A-5, with the initial A3J-1 becoming A-5A and the updated A3J-2 becoming A-5B. The subsequent reconnaissance version, originally A3J-3P, became the RA-5C.

The Vigilante's early service proved troublesome, with many teething problems for its advanced systems. Although these systems were highly sophisticated, the technology was in its infancy and its reliability was poor.[12] Although most of these reliability issues were eventually worked out as maintenance personnel gained greater experience with supporting these systems, the aircraft tended to remain a maintenance-intensive platform throughout its career.

The A-5's service coincided with a major policy shift in the U.S. Navy's strategic role, which switched to emphasize submarine-launched ballistic missiles rather than manned bombers. As a result, in 1963, procurement of the A-5 was ended and the type was converted to the fast reconnaissance role. The first RA-5Cs were delivered to VAH-3, the A-5A and A-5B Replacement Air Group (RAG)/Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS), subsequently redesignated as Reconnaissance Attack Squadron Three (RVAH-3), at NAS Sanford, Florida in July 1963. As they transitioned from the attack version to the reconnaissance version, all Vigilante squadrons were subsequently redesignated from VAH to RVAH.

Under Commander, Reconnaissance Attack Wing One (COMRECONATKWING ONE), a total of 10 RA-5C squadrons were ultimately established. RVAH-3 continued to be responsible for the stateside-based RA-5C training mission of flight crews, maintenance and support personnel, while RVAH-1, RVAH-5, RVAH-6, RVAH-7, RVAH-9, RVAH-11, RVAH-12, RVAH-13 and RVAH-14 routinely deployed aboard Forrestal, Saratoga, Ranger, Independence, Kitty Hawk, Constellation, Enterprise, America, John F. Kennedy and eventually the Nimitz-class aircraft carriers to the Atlantic, Mediterranean and Western Pacific.

Eight of ten squadrons of RA-5C Vigilantes also saw extensive service in the Vietnam War starting in August 1964, carrying out hazardous medium-level post-strike reconnaissance missions. Although it proved fast and agile, 18 RA-5Cs were lost in combat: 14 to anti-aircraft fire, 3 to surface-to-air missiles, and 1 to a MiG-21 during Operation Linebacker II. Nine more RA-5Cs were lost in operational accidents while serving with Task Force 77. Due, in part, to these combat losses, 36 additional RA-5C aircraft were built from 1968 to 1970 as attrition replacements.[13]

In 1968, Congress closed the aircraft's original operating base of NAS Sanford, Florida and transferred the parent wing, Reconnaissance Attack Wing One, all subordinate squadrons and all aircraft and personnel to Turner AFB, a Strategic Air Command (SAC) Boeing B-52 Stratofortress and Boeing KC-135 base in Albany, Georgia. The tenant SAC bomb wing was then inactivated and control of Turner AFB was transferred from the Air Force to the Navy with the installation renamed Naval Air Station Albany. In 1974, after barely six years of service as a naval air station, Congress opted to close NAS Albany as part of a post-Vietnam force reduction, transferring all RA-5C units and personnel to NAS Key West, Florida.

Despite the Vigilante's useful service, it was expensive and complex to operate and occupied significant amounts of precious flight deck and hangar deck space aboard both conventional and nuclear-powered aircraft carriers at a time when carrier air wings, with the introduction of the F-14 Tomcat and S-3 Viking, were averaging 90 aircraft, many of which were larger than their predecessors. With the end of the Vietnam War, disestablishment of RVAH squadrons began in 1974, with the last Vigilante squadron, RVAH-7, completing its final deployment to the Western Pacific aboard USS Ranger in late 1979. The final flight by an RA-5C took place on 20 November 1979 when a Vigilante departed NAS Key West, Florida.[14] Reconnaissance Attack Wing One was subsequently disestablished at NAS Key West, Florida in January 1980.

The Vigilante did not end the career of the A-3 Skywarrior, which would carry on as photo reconnaissance aircraft, electronic warfare platforms, aerial refueling tankers, and executive transport aircraft designated as RA-3A/B, EA-3A/B, ERA-3B, EKA-3B KA-3B, and VA-3B, into the early 1990s.

Fighters replaced the RA-5C in the carrier-based reconnaissance role. The RF-8G version of the Vought F-8 Crusader, modified with internal cameras, had already been serving in two light photographic squadrons (VFP-62 and VFP-63) since the early 1960s, operating from older aircraft carriers unable to support the Vigilante. The Marine Corps' sole photographic squadron (VMFP-3) would also deploy aboard aircraft carriers during this period with RF-4B Phantom II aircraft. These squadrons superseded the Vigilante's role by providing detachments from the primary squadron to carrier air wings throughout the late 1970s and early-to-mid-1980s, until the transfer of the recon mission to the Navy's fighter squadron (VF) community operating the F-14 Tomcat. Select models of the F-14 Tomcat would eventually carry the multi-sensor Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS) and the Digital Tactical Air Reconnaissance Pod (D-TARPS). Up to present day, the weight of carrier-based fighters such as the F-14 Tomcat and Boeing F/A-18E/F Super Hornet have evolved into the same 62,950 lb (28,550 kg) class as the Vigilante.

Records

On 13 December 1960, Navy Commander Leroy Heath (Pilot) and Lieutenant Larry Monroe (Bombardier/Navigator) established a world altitude record of 91,450.8 feet (27,874.2 m) in an A3J Vigilante carrying a 1,000 kilogram payload, beating the previous record by over 4 miles (6.4 km). This new record held for more than 13 years.[15] The attempt was accomplished by reaching a speed of Mach 2.1, then pulling up to create a ballistic trajectory beyond the altitude at which its wings could continue to function. The engines flamed out in the thin atmosphere, and the aircraft rolled onto its back. This had already been experienced in previous flights, and so the pilot simply released the controls and the aircraft regained control naturally as it descended back into the thicker air of the lower atmosphere.[16]

Variants

- XA3J-1

- (NA247) Prototypes, two built, one converted to RA-5C, one crashed 1959.

- A3J-1

- 58 built, 6 cancelled, survivors re-designated A-5A in 1962, 42 converted to RA-5C.

- A3J-2

- 18 built, redesignated A-5B, 5 completed as XA3J-3P (YA-5C), all converted to RA-5C.

- XA3J-3P

- 5 x A3J-2 completed from A3J-2 order without reconnaissance systems and assigned to pilot familiarization, later converted to RA-5C.

- A3J-3P

- 20 built, re-designated RA-5C.

- A-5A

- A3J-1 re-designated.

- A-5B

- A3J-2 re-designated.

- YA-5C

- The 5 XA3J-3P aircraft re-designated, before conversion to RA-5C

- RA-5C

- Reconnaissance aircraft, 77 contracted, 8 cancelled, 69 built, plus 20 redesignated and 61 converted from earlier variants

- NR-349

- Proposed Improved Manned Interceptor for U.S. Air Force with three J79 engines and an armament of six AIM-54 Phoenix missiles.[17]

Aircraft on display

- A-5A

- BuNo 146697 - Patuxent River NAS, Lexington Park, Maryland. It is the oldest Vigilante on display and the only one still in its original A3J/A-5A nuclear attack bomber configuration.[18]

An additional example of an A-5A destined for restoration as a museum aircraft, BuNo 146698, was destroyed when it was being relocated by Army helicopter from Naval Air Engineering Station Lakehurst, New Jersey to a new location. When the A-5A became unstable in flight, the helicopter crew was forced to jettison the aircraft from altitude.[19]

- RA-5C

- BuNo 149289 - Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona. It was transferred from long-term storage at nearby Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and it carries the markings of RVAH-3.[20]

- BuNo 151629 - Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum (formerly the Fred E. Weisbrod Museum/International B-24 Museum) in Pueblo, Colorado. It has been restored and currently displays the markings of RVAH-7 while assigned to Carrier Air Wing 9 aboard Enterprise.[21]

- BuNo 156608 - Naval Support Activity Mid-South, formerly Naval Air Station Memphis, Tennessee. It was the last operational RA-5C aircraft and it carries the markings of its last squadron, RVAH-7, during its final deployment with Carrier Air Wing 2 aboard Ranger in 1979.[22]

- BuNo 156612 - Naval Air Station Key West, Florida. "Gate guard" aircraft located just inside the main gate. It carries the markings of RVAH-3.[23]

- BuNo 156615 - Castle Air Museum at the former Castle Air Force Base, California in 2012. This aircraft was formerly located on the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake Range. This particular RA-5C was the last Vigilante to land aboard the USS Ranger (CV-61) while assigned to RVAH-7 in August 1979 during the last Vigilante overseas carrier deployment.[24]

- BuNo 156621 - New York State Aerosciences Museum (ESAM) in Glenville, New York. It was initially on display at the former US Naval Photographic School at NAS Pensacola, Florida. In 1986, it was shipped up the East Coast by barge and placed on display aboard the USS Intrepid Museum in New York City. In 2005, this RA-5C was acquired by ESAM. The aircraft suffered minor damage to its fuselage aft of the wing root while being moved from the aircraft carrier Intrepid to a barge while supported by slings. It is currently (as of 2010) undergoing restoration for display. It carries the markings of the RA-5C Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS), RVAH-3.[25]

- BuNo 156624 - National Naval Aviation Museum at NAS Pensacola, Florida. It is displayed in the markings of RVAH-6 per that squadron's final cruise with Carrier Air Wing 8 aboard Nimitz in 1978.[26]

- BuNo 156632 - Orlando Sanford International Airport (formerly Naval Air Station Sanford) in Sanford, Florida. It was placed there on 30 May 2003 as a memorial to A-5A and RA-5C aircrewmen and support personnel who served at NAS Sanford. On loan from the National Museum of Naval Aviation, the aircraft was transferred from the Naval Air Systems Command (NAVAIR) Weapons Division at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California and is marked as an RVAH-3 aircraft.[27]

- BuNo 156638 - Naval Air Station Fallon, Nevada. It was transferred from Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California and was previously marked as an RVAH-6 aircraft in a Vietnam-era jungle camouflage paint scheme, as an RVAH-12 aircraft in traditional Cold War gray/white paint scheme, and currently as an RVAH-7 aircraft in traditional gray/white paint scheme.[28]

- BuNo 156641 - USS Midway Museum in San Diego, California. It carries the markings of RVAH-12 and RVAH-7 Both squadrons represented on the tail of the aircraft.[29]

- BuNo 156643 - Patuxent River Naval Air Museum, at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland. It was transferred from NAS Key West, Florida, and is displayed as a test aircraft operated by the Patuxent River Flight Test Division in the 1970s. It was the last RA-5C built.[30]

- As of 2004, all RA-5C airframes previously stored with the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group at Davis-Monthan AFB, Arizona, have either been scrapped or relocated, with some of these aircraft expended as ground targets in aerial bomb and guided missile tests. A small number of RA-5C airframes in various states of condition are currently stored at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California. A number of previous examples were expended as ground targets on weapon ranges at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California and Eglin Air Force Base, Florida.

Specifications (A-5A Vigilante)

Data from North American Rockwell A3J (A-5) Vigilante,[31], Aircraft engines of the World 1966/67,[32] Jane's all the World's Aircraft 1964–65[33]}

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Length: 76 ft 6 in (23.32 m)

- Wingspan: 53 ft 0 in (16.16 m)

- Height: 19 ft 5 in (5.91 m)

- Wing area: 701 sq ft (65.1 m2)

- Empty weight: 32,783 lb (14,870 kg)

- Gross weight: 47,631 lb (21,605 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 63,085 lb (28,615 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × General Electric J79-GE-8 after-burning turbojet engines, 10,900 lbf (48 kN) thrust each dry, 17,000 lbf (76 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,149 kn (1,322 mph, 2,128 km/h) at 40,000 ft (12,000 m)

- Maximum speed: Mach 2

- Combat range: 974 nmi (1,121 mi, 1,804 km) (to target and return)

- Ferry range: 1,571 nmi (1,808 mi, 2,909 km)

- Service ceiling: 52,100 ft (15,900 m)

- Rate of climb: 8,000 ft/min (41 m/s)

- Wing loading: 80.4 lb/sq ft (393 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.72

Armament

- Bombs:

- 1× B27, B28 or B43 freefall nuclear bomb in internal weapons bay

- 2× B43, Mark 83, or Mark 84 bombs on two external hardpoints

Avionics

Systems carried by A-5 or RA-5C[34][35]

- AN/ASB-12 Bombing & Navigation Radar (A-5, RA-5C)

- Westinghouse AN/APD-7 SLAR (RA-5C)

- Sanders AN/ALQ-100 E/F/G/H-Band Radar Jammer (RA-5C)

- Sanders AN/ALQ-41 X-Band Radar Jammer (A-5, RA-5C)

- AIL AN/ALQ-61 Radio/Radar/IR ECM Receiver (RA-5C)

- Litton ALR-45 "COMPASS TIE" 2-18 GHz Radar Warning Receiver (RA-5C)

- Magnavox AN/APR-27 SAM Radar Warning Receiver (RA-5C)

- Itek AN/APR-25 S/X/C-Band Radar Detection and Homing Set (RA-5C)

- Motorola AN/APR-18 Electronic Reconnaissance System (A-5, RA-5C)

- AN/AAS-21 IR Reconnaissance Camera (RA-5C)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Related lists

References

Notes

Citations

- Wagner 1982, p. 361.

- Dean 2001, p. 23.

- Siuru 1981, p. 15.

- Siuru 1981, p. 16.

- Aerofax Minigraph 9: North American Rockwell A3J/A-5 Vigilante; Michael Grove and Jay Miller; Aerofax, Inc., Arlington, TX; c1989; p.41

- Ellis 2008, p. 64.

- Thomason 2009, p. 112.

- Goebel, Greg. "The North American A-5/RA-5 Vigilante". Archived from the original on 2016-02-02. Retrieved 2016-01-19. airvectors.net, 5 April 2007. Retrieved: 2 March 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-11-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-10-15. Retrieved 2013-12-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Goodspeed 2000, p. 51.

- Aerofax Minigraph 9: North American Rockwell A3J/A-5 Vigilante; Michael Grove and Jay Miller; Aerofax, Inc., Arlington, TX; c1989; pp. 6-10

- Ellis 2008, p. 63.

- Grossnick, Roy A. (1997). "Part 10 The Seventies". United States Naval Aviation 1910–1995 (pdf). history.navy.mil. pp. 324–325. ISBN 0-945274-34-3. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Siuru, 1981, p. 16

- "North American Rockwell A3J (A-5) Vigilante" by M. Hill Goodspeed, WINGS OF FAME, Volume 19 (2000)

- Buttler 2007, p. 182.

- "A-5 Vigilante/146697." Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "RA-5C Vigilante History". www.bobjellison.com. Archived from the original on 2015-02-11.

- "A-5 Vigilante/149289." Archived 2015-06-25 at the Wayback Machine Pima Air & Space Museum. Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/151629." Archived 2013-10-30 at the Wayback Machine Pueblo Weisbrod Aircraft Museum. Retrieved: 13 December 2012.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156608." Archived 2015-06-25 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156612." Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156615." Archived 2016-11-14 at the Wayback Machine Castle Air Museum. Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156621." Archived 2015-06-25 at the Wayback Machine Empire State Aerosciences Museum. Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156624." Archived 2017-07-05 at the Wayback Machine National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156632." Archived 2015-06-25 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156638." Archived 2015-06-24 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156641." Archived 2013-03-25 at the Wayback Machine USS Midway Museum. Retrieved: 13 December 2012.

- "A-5 Vigilante/156643." Archived 2015-06-25 at the Wayback Machine aerialvisuals.ca Retrieved: 24 June 2015.

- Goodspeed 2000, p. 77.

- Wilkinson, Paul H. (1966). Aircraft engines of the World 1966/67 (21st ed.). London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Ltd. p. 84.

- Taylor, John W.R., ed. (1964). Jane's all the World's Aircraft 1964–65. London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, Ltd. p. 274.

- Parsch, Andreas. "Designations of US Military Electronic and Communications Equipment." Archived 2015-04-28 at the Wayback Machine Designation Systems, 5 June 2011. Retrieved: 31 January 2012.

- Eden 2009, pp. 220, 221.

Bibliography

- Buttler, Tony. American Secret Projects: Fighters & Interceptors 1945–1978. Hinckley, UK: Midland Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-1-85780-264-1.

- Buttler, Tony. "Database: North American A3J/A-5 Vigilante". Aeroplane, Vol. 42, No. 7, July 2014. pp. 69–84.

- Butowski, Piotr with Jay Miller. OKB MiG: A History of the Design Bureau and Its Aircraft. Leicester, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1991. ISBN 978-0-904597-80-6.

- Dean, Jack. "Sleek Snooper." Airpower, Volume 31, No. 2, March 2001.

- Donald, David and Jon Lake, eds. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 1996. ISBN 1-880588-24-2.

- Eden. Paul. Modern Military Aircraft Anatomy. London: Amber Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1-905704-77-4.

- Ellis, Ken, ed. "North American A-5 Vigilante" (In Focus). Flypast, August 2008.

- Goodspeed, M. Hill. "North American Rockwell A3J (A-5) Vigilante". Wings of Fame, Volume 19, pp. 38–103. London: Aerospace Publishing, 2000. ISBN 1-86184-049-7.

- Gunston, Bill. Bombers of the West. London: Ian Allan Ltd., 1973, pp. 227–35. ISBN 0-7110-0456-0.

- Powell, Robert. RA-5C Vigilante Units in Combat (Osprey Combat Aircraft #51). Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing Limited, 2004. ISBN 1-84176-749-2.

- Siuru, William. "Vigilante: Farewell to the Fleet's Last Strategic Bomber!" Airpower, Volume 11, No. 1, January 1981.

- Taylor, John W. R. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1965–66. London: Sampson Low, Marston, 1965.

- Taylor, John W.R. "North American A-5 Vigilante." Combat Aircraft of the World from 1909 to the Present. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1969. ISBN 0-425-03633-2.

- Thomason, Tommy H. "Strike from the Sea". North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2009. ISBN 978-1580071321 .

- Wagner, Ray. American Combat Planes. Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, third edition 1982. ISBN 0-385-13120-8.

- Wilson, Stewart. Combat Aircraft since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications, 2000. ISBN 1-875671-50-1

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to A-5 Vigilante. |