Dutch Island (Rhode Island)

Dutch Island is an island lying west of Conanicut Island at an entrance to Narragansett Bay in Rhode Island, United States. It is part of the town of Jamestown, Rhode Island, and has a land area of 0.4156 km² (102.7 acres). It was uninhabited as of the United States Census, 2000. The island was fortified from the American Civil War through World War II and was known as Fort Greble from 1898 to 1947.

History

Dutch Island's Indian name was Quotenis or Quetenesse. Abraham Pietersen van Deusen of the Dutch West India Company established a trading post on the island around 1636 to trade with the Narragansett Indians, trading Dutch goods, cloths, implements, and liquors for the Indians' furs, fish, and venison. Several years later, the Dutch built Fort Ninigret in Charlestown. In 1654, English colonists purchased the island from the Indians. In 1825, the federal government acquired 6 acres (24,000 m2) at the southern end of the island, and Dutch Island Light was established on January 1, 1827 to mark the west passage of Narragansett Bay and to aid vessels entering Dutch Island Harbor. The first 30-foot (9.1 m) tower was built of stones found on the island. The government constructed a new 42-foot (13 m) brick tower in 1857 with a fog bell added in 1878. No remnants exist today of the Dutch trading post, but a lighthouse and military buildings remain on the island.

Fort Greble

| Fort Greble | |

|---|---|

| Part of Harbor Defenses of Narragansett Bay | |

| Dutch Island, Rhode Island | |

.jpg) A 10-inch disappearing gun at Fort Greble. | |

Fort Greble Location in Rhode Island | |

| Coordinates | 41°30′14″N 71°24′00″W |

| Type | Coastal Defense, later POW camp |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Rhode Island Dept of Environmental Management |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | Fair |

| Site history | |

| Built | circa 1895 |

| Built by | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1897-1947 |

| Battles/wars | World War I, World War II |

Fort Greble was named in honor of 1st Lt. John Trout Greble, 2nd Artillery, USA, who was the first officer of the Regular Army killed in the Civil War. In 1863, the land was sold to the United States government, and the island was taken over by the Army by 1864.

American Civil War

During the American Civil War, the island was used as a training site by the 14th Rhode Island Heavy Artillery (Colored). The soldiers of the 14th Rhode Island constructed the first earthwork defenses on the island, and sporadic construction continued after the Civil War ended. An eight-gun battery was built and armed by the 14th Rhode Island in 1863-64. A battery for eleven 10-inch Rodman guns was also built at the south end of the island; it extended in a north-south line and had wide arcs of fire on either side. However, it was vulnerable to flooding and was never armed.[1]

Spanish American War

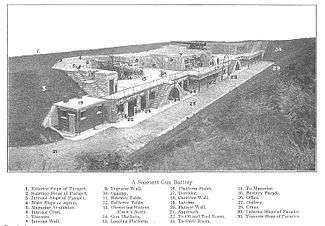

More gun batteries were placed on Dutch Island after the Civil War. In 1870, a massive fort was proposed for Dutch Island mounting forty 15-inch Rodman guns, but funding for this was cut off in 1875, and nearly all coast defense funding was cut off nationwide within a few years.[2] However, the recommendations of the Endicott Board in the late 1890s resulted in the construction of Fort Greble as part of the Coast Defenses of Narragansett Bay. This was spurred by the Spanish–American War and included tunnels and gun emplacements, with the fort enlarged until 1902. The first of Fort Greble's works was Battery Hale, completed in 1897 with the emplacement of three 10-inch M1888 disappearing guns. A battery was constructed for one 6-inch Armstrong gun shortly after the war started, but the gun was removed in 1903.[3] This was followed by the establishment of Battery Mitchell on the Armstrong gun site with three 6-inch M1903 disappearing guns, and Battery Sedgwick with eight 12-inch M1890 mortars. Finally Battery Ogden was completed in 1900 with its two 3-inch M1898 rapid fire guns on retractable masking parapet carriages. The fort also had facilities for controlling an underwater minefield, and the mines were stored at Fort Wetherill.[4][5]

Battery Hale was named for Revolutionary War hero Nathan Hale. Battery Mitchell was named for Captain David D. Mitchell, killed in the Philippine-American War. Battery Sedgwick was named for Major-General John Sedgwick, killed in the Civil War. Battery Ogden was named for Frederick C. Ogden, an officer killed in the Civil War.[4]

Inter-war period training exercises

The New York Times reported that a combined arms training exercise was conducted on 26 June 1908 involving regular and militia military units from Fort Adams and Fort Greble. Soldiers and their commanders launched a simulated land and sea attack on the island, and the residents of Newport and Jamestown were kept awake all night by the sound of the fort's guns.

Corporal William W. Lee loaded two pounds of the wrong powder into Fort Greble's reveille gun on 2 April 1912, which typically used only 4 ounces or 8 tablespoons of black powder, and the breech blew up when he pulled the lanyard. His wounds were fatal, and his grave is located in Jamestown's town cemetery on Narragansett Ave.[6]

World Wars 1 and 2

The fort was home to as many as 495 soldiers during World War I under the command of Colonel Charles Foster Tillinghast, Sr. Several of its guns were dismounted for potential service on the Western Front in 1917-18. One 10-inch gun of Battery Hale was dismounted for conversion to a railway gun; it was replaced by a similar gun from Fort Wetherill in late 1918. The three 6-inch guns of Battery Mitchell were dismounted in 1917 and sent to France for use on wheeled carriages; they were not returned to Fort Greble. None of the 6-inch gun regiments completed training before the Armistice of 11 November 1918 and thus did not see combat.[4][7] Four of Battery Sedgwick's eight 12-inch mortars were dismounted in 1918 for potential use as railway artillery and to improve reloading efficiency.[4]

Battery Ogden's 3-inch guns were withdrawn from service in 1920 as part of a general retirement of the M1898 3-inch guns.[4] The fort was active till the mid-1920s as part of the Coast Defenses of Narragansett Bay. It was placed in caretaker status because the fort's cisterns were defective and could not hold sufficient water to support the garrison.

During World War II, Fort Greble was used as a German prisoner-of-war camp and was discontinued from service in 1947. The fort's guns were scrapped in 1942 once improved defenses were constructed centered on Fort Church and Fort Greene.[4][5]

Since World War 2

There have been no redevelopment or preservation efforts on Dutch Island since World War 2, and it has been used as a training site for the Rhode Island National Guard. The island is owned by the State of Rhode Island and is designated as a wildlife management area by the state's Department of Environmental Management (DEM). In 2016, the Army Corps of Engineers completed a project to mitigate safety hazards on the island.

Gallery

.jpg) 12-inch mortar pit at Fort Greble.

12-inch mortar pit at Fort Greble..jpg) 6-inch disappearing gun at Fort Greble.

6-inch disappearing gun at Fort Greble. 3-inch gun M1898 on retractable masking parapet carriage M1898, the type that was at Fort Greble

3-inch gun M1898 on retractable masking parapet carriage M1898, the type that was at Fort Greble.jpg) Fort Greble from the ferry.

Fort Greble from the ferry..jpg) Testing a mine, Fort Greble.

Testing a mine, Fort Greble.

References

- Schroder 1998, pp. 14-18

- Schroder 1998, pp. 20-21

- Congressional serial set, 1900, Report of the Commission on the Conduct of the War with Spain, Vol. 7, pp. 3778-3780, Washington: Government Printing Office

- FortWiki article on Fort Greble

- Berhow, p. 205

- Corporal Killed as He Fires Morning Gun, Boston Journal, 3 April 1912

- History of the Coast Artillery Corps in World War I

- Dutch Island: Block 4050, Census Tract 415, Newport County, Rhode Island United States Census Bureau

- Dutch Island Lighthouse History

- Lighthouse Details

- Berhow, Mark A., Ed. (2004). American Seacoast Defenses, A Reference Guide, Second Edition. CDSG Press. ISBN 0-9748167-0-1.

- Frederic Denlson, Narragansett Sea and Shore, (J.A. & R.A. Reid, Providence, RI., 1879)

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Schroder, Walter K. (1998). Images of America: Dutch Island and Fort Greble. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-6365-7.

- George L. Seavey, Rhode Island's Coastal Natural Areas.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dutch Island (Rhode Island). |

- List of all US coastal forts and batteries at the Coast Defense Study Group, Inc. website

- FortWiki, lists all CONUS and Canadian forts