Qalandariyya

The Qalandariyyah (Arabic: قلندرية), Qalandaris, Qalandars or Kalandars are wandering ascetic Sufi dervishes. The term covers a variety of sects, not centrally organized and may not be connected to a specific tariqat. One was founded by Qalandar Yusuf al-Andalusi of Andalusia, Spain. They were mostly in Iran, Central Asia, India and Pakistan.

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

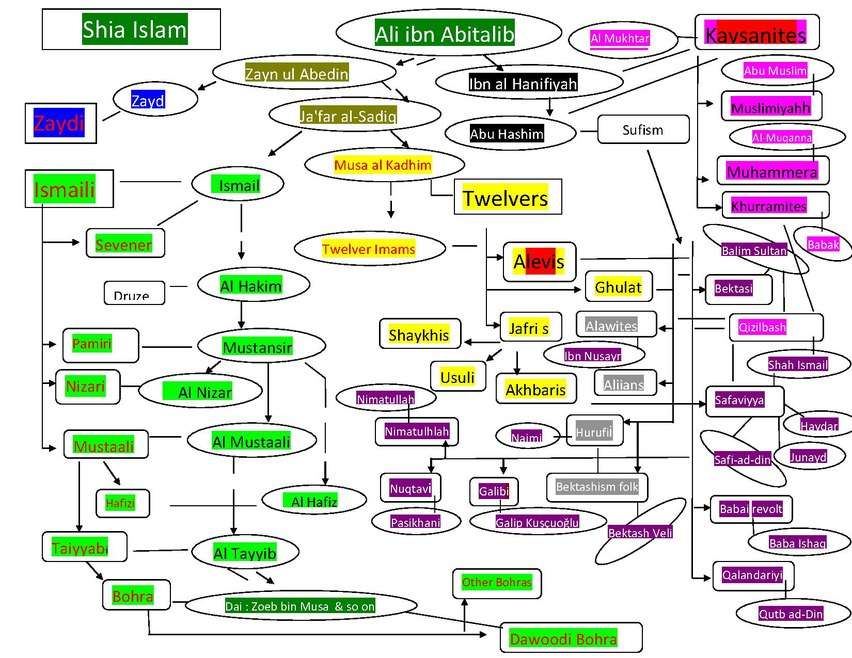

| Part of a series on Islam Shia Islam |

|---|

|

|

Beliefs and practices |

|

|

Holy women |

|

|

| Part of a series on Islam Sufism |

|---|

|

List of sufis |

|

|

Starting in the early 12th century, the movement gained popularity in Greater Khorasan and neighbouring regions, including South Asia.[1] The first references are found in the 11th-century prose text Qalandarname (The Tale of the Kalandar) attributed to Ansarī Harawī. The term Qalandariyyat (the Qalandar condition) appears to be first applied by Sanai Ghaznavi (died 1131) in seminal poetic works where diverse practices are described. Particular to the qalandar genre of poetry are terms that refer to gambling, games, intoxicants and Nazar ila'l-murd, themes commonly referred to as kufriyyat or kharabat. The genre was further developed by poets such as Fakhr-al-Din Iraqi and Farid al-Din Attar.

Origin

The Qalandariyya are an unorthodox tariqa of Sufi dervishes that originated in medieval al-Andalus as an answer to the state sponsored Zahirism of the Almohad Caliphate. From there they quickly spread into North Africa, the Mashriq, Greater Iran, Central Asia and Pakistan [2][3]

Qalandariyya in South Asia

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| The Fourteen Infallibles | |||

|

|||

| Principles | |||

| Other beliefs | |||

| Practices | |||

|

Others

|

|||

| Holy cities | |||

| Groups | |||

|

|

|||

| Scholarship | |||

| Hadith collections | |||

|

|||

| Related topics | |||

| Related portals | |||

|

|||

The Qalandariya may have arisen from the earlier Malamatiyya and exhibited some Buddhist and Hindu influences in South Asia.[4] The Malamatiya condemned the use of drugs and dressed only in blankets or in hip-length hairshirts.[5]

The writings of qalandars were not a mere celebration of libertinism, but antinomial practices of affirmation from negative action. The order was often viewed suspiciously by authorities.

The term remains in popular culture. Sufi qawwali singers the Sabri brothers and international Qawwali star Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan favoured the chant dam a dam masta qalandar (with every breath ecstatic Qalandar!), and a similar refrain appeared in a hit song from Runa Laila from movie Ek Se Badhkar Ek that became a dancefloor crossover hit in the 1970s.

In Pakistan and North India, descendants of Qalandariyah faqirs now form a distinct community, known as the Qalandar biradari.

Dhamaal

Songs honoring famous qalandars are called qalandri dhamaal in Pakistan. Dhamaal are a popular South Asian musical subgenre about Sufi saints such as Lal Shahbaz Qalandar. These songs typically incorporate qawwali styles as well as different local folk styles, such as bhangra and intense naqareh or dhol drumming.[12]

See also

Bibliography

- De Bruijn, The Qalandariyyat in Persian Mystical Poetry from Sana'i, in The Heritage of Sufism, 2003.

- Ashk Dahlén, The Holy Fool in Medieval Islam: The Qalandariyat of Fakhr al-din Araqi, Orientalia Suecana, vol.52, 2004.

References

- Merriam-Webster's Encyclopædia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. 1999. p. 896. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

The movement is first mentioned in Khorasan in the 11th century; from there it spread to India, Syria, and western Iran.

- Ivanov, Sergej Arkadevich (2006) Holy fools in Byzantium and beyond Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, page 368, ISBN 0-19-927251-4

- de Bruijn, J. T. P. "The Qalandariyyat in Persian Mystical Poetry from Sand'i Onwards". In Lewisohn, Leonard (ed.) (1992) The Legacy of Mediæval Persian Sufism Khaniqahi Nimatullahi, London, pp. 61–75, ISBN 0-933546-45-9

- Merriam-Webster's Encyclopædia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. 1999. p. 896. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

The Qalandariya seem to have arisen from the earlier MALAMATIYA in Central Asia and exhibited Buddhist and perhaps Hindu influences.

- Merriam-Webster's Encyclopædia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. 1999. p. 896. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

The Qalandariya seem to have arisen from the earlier MALAMATIYA in Central Asia and exhibited Buddhist and perhaps Hindu influences.

- Balcıoğlu, Tahir Harimî, Türk Tarihinde Mezhep Cereyanları - The course of madhhab events in Turkish history, (Preface and notes by Hilmi Ziya Ülken), Ahmet Sait Press, 271 pages, Kanaat Publications, Istanbul, 1940. (in Turkish)

- Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar XII yüzyılda Anadolu'da Babâîler İsyânı - Babai Revolt in Anatolia in the Twelfth Century, pages 83-89, Istanbul, 1980. (in Turkish)

- "Encyclopaedia of Islam of the Foundation of the Presidency of Religious Affairs," Volume 4, pages 373-374, Istanbul, 1991.

- Balcıoğlu, Tahir Harimî, Türk Tarihinde Mezhep Cereyanları - The course of madhhab events in Turkish history – Two crucial front in Anatolian Shiism: The fundamental Islamic theology of the Hurufiyya madhhab, (Preface and notes by Hilmi Ziya Ülken), Ahmet Sait Press, page 198, Kanaat Publications, Istanbul, 1940. (in Turkish)

- According to Turkish scholar, researcher, author and tariqa expert Abdülbaki Gölpınarlı, "Qizilbashs" ("Red-Heads") of the 16th century - a religious and political movement in Azerbaijan that helped to establish the Safavid dynasty - were nothing but "spiritual descendants of the Khurramites". Source: Roger M. Savory (ref. Abdülbaki Gölpinarli), Encyclopaedia of Islam, "Kizil-Bash", Online Edition 2005.

- According to the famous Alevism expert Ahmet Yaşar Ocak, "Bektashiyyah" was nothing but the reemergence of Shamanism in Turkish societies under the polishment of Islam. (Source: Ocak, Ahmet Yaşar XII yüzyılda Anadolu'da Babâîler İsyânı - Babai Revolt in Anatolia in the Twelfth Century, pages 83-89, Istanbul, 1980. (in Turkish))

- Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2006). Culture and customs of Pakistan. Greenwood Press, Westport, Connecticut, page 171, ISBN 0-313-33126-X