Kairouan

Kairouan (Arabic: القيروان ![]()

![]()

Kairouan القيروان | |

|---|---|

| |

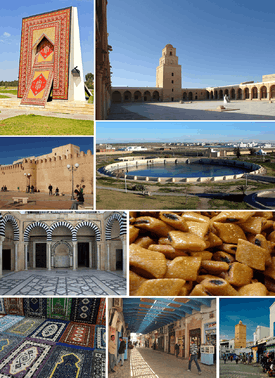

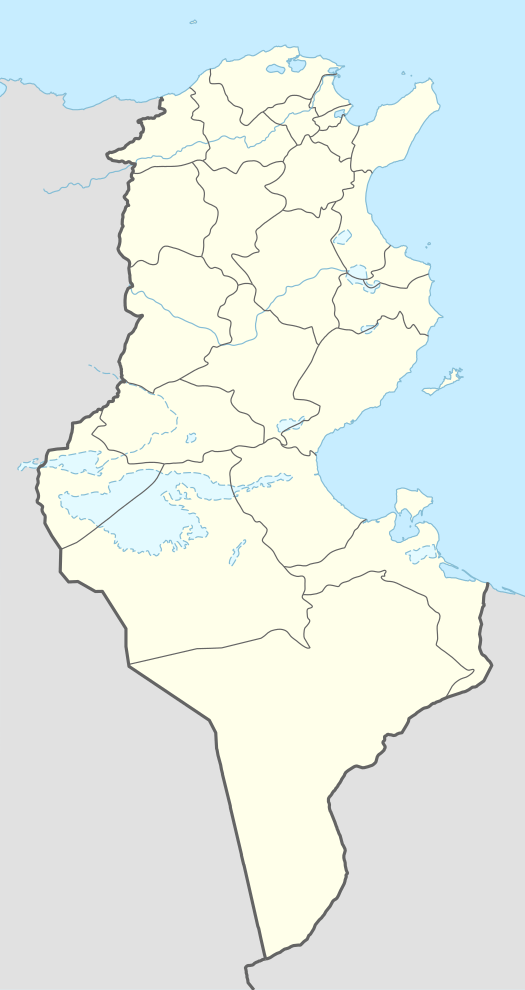

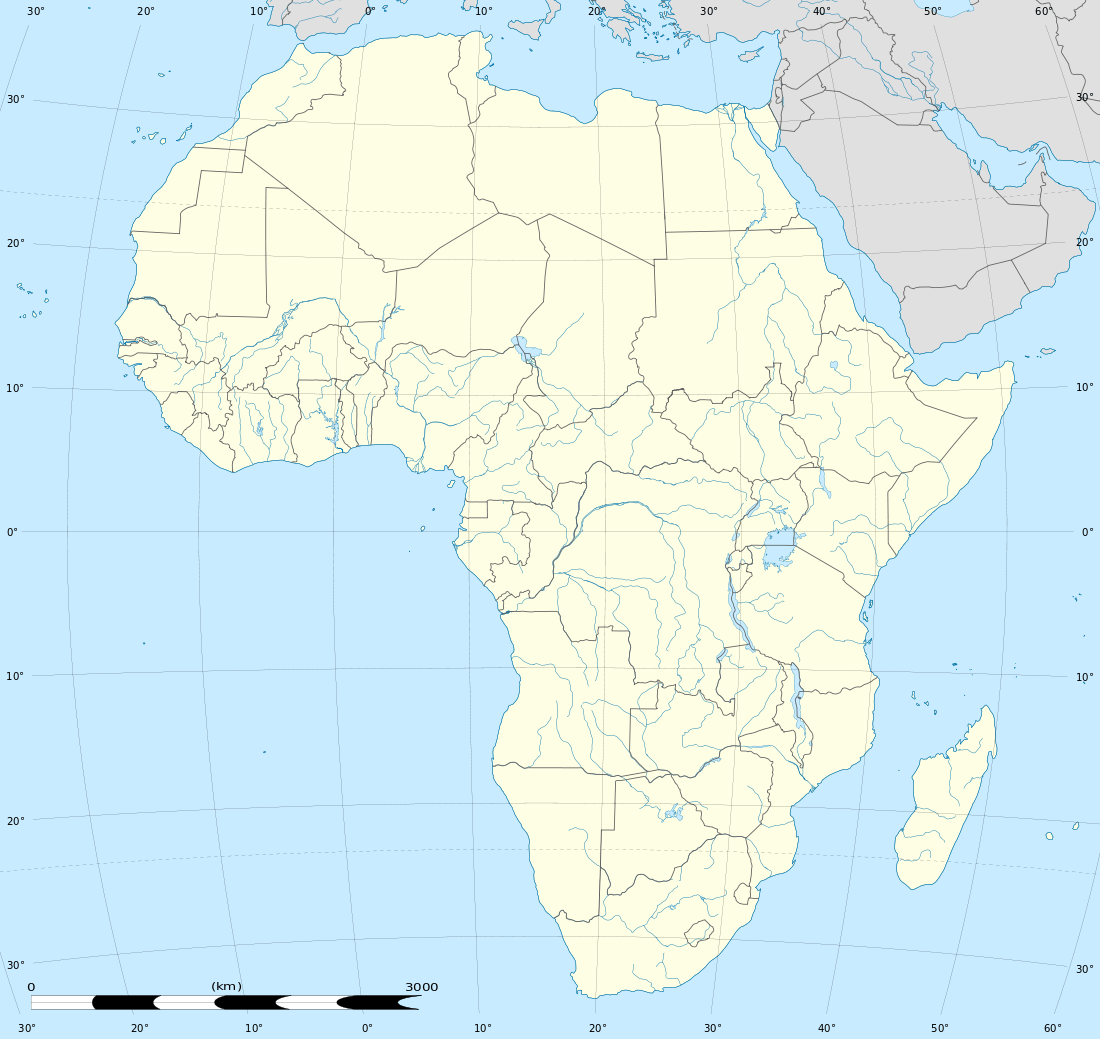

Kairouan Location in Tunisia  Kairouan Kairouan (Middle East)  Kairouan Kairouan (Africa) | |

| Coordinates: 35°40′38″N 10°06′03″E | |

| Country | Tunisia |

| Governorate | Kairouan |

| Founded | 670 CE |

| Founded by | Uqba ibn Nafi |

| Elevation | 68 m (223 ft) |

| Population (2014) | |

| • Total | 187,000 |

| Website | Official website |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, v, vi |

| Reference | 499 |

| Inscription | 1988 (12th session) |

| Area | 68.02 ha |

| Buffer zone | 154.36 ha |

In 2014, the city had about 187,000 inhabitants.

Etymology

The name (ٱلْقَيْرُوَان Al-Qairuwân) is an Arabic deformation of the Persian word کاروان kârvân, meaning "military/civilian camp" (kâr war/military, akin to Latin guer + vân outpost), "caravan", or "resting place" (see caravanserai).[5][6][7]

Geography

Kairouan, the capital of Kairouan Governorate, lies south of Sousse, 50 km (31 mi) from the east coast, 75 km (47 mi) from Monastir and 184 km (114 mi) from Tunis.

History

.png)

The foundation of Kairouan dates to about the year 670 when the Arab general Uqba ibn Nafi of Caliph Mu'awiya selected a site in the middle of a dense forest, then infested with wild beasts and reptiles, as the location of a military post for the conquest of the West. Formerly, the city of Kamounia was located where Kairouan now stands. It had housed a Byzantine garrison before the Arab conquest, and stood far from the sea – safe from the continued attacks of the Berbers who had fiercely resisted the Arab invasion. Berber resistance continued, led first by Kusaila, whose troops killed Uqba at Biskra about fifteen years after the establishment of the military post,[8] and then by a Berber woman called Al-Kahina who was killed and her army defeated in 702. Subsequently, there occurred a mass conversion of the Berbers to Islam. Kharijites or Islamic "outsiders" who formed an egalitarian and puritanical sect appeared and are still present on the island of Djerba. In 745, Kharijite Berbers captured Kairouan, which was already at that time a developed city with luxuriant gardens and olive groves. Power struggles continued until Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab recaptured Kairouan at the end of the 8th century. In 800 Caliph Harun ar-Rashid in Baghdad confirmed Ibrahim as Emir and hereditary ruler of Ifriqiya. Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab founded the Aghlabid dynasty which ruled Ifriqiya between 800 and 909. The new Emirs embellished Kairouan and made it their capital. It soon became famous for its wealth and prosperity, reaching the levels of Basra and Kufa and giving Tunisia one of its golden ages long sought after the glorious days of Carthage.

The Aghlabites built the great mosque and established in it a university that was a centre of education both in Islamic thought and in the secular sciences. Its role can be compared to that of the University of Paris in the Middle Ages. In the 9th century, the city became a brilliant focus of Arab and Islamic cultures attracting scholars from all over the Islamic World. In that period Imam Sahnun and Asad ibn al-Furat made of Kairouan a temple of knowledge and a magnificent centre of diffusion of Islamic sciences. The Aghlabids also built palaces, fortifications and fine waterworks of which only the pools remain. From Kairouan envoys from Charlemagne and the Holy Roman Empire returned with glowing reports of the Aghlabites palaces, libraries and gardens – and from the crippling taxation imposed to pay for their drunkenness and sundry debaucheries. The Aghlabite also pacified the country and conquered Sicily in 827.[9]

.png)

In 893, through the mission of Abdullah al Mahdi, the Kutama Berbers from the west of the country started the movement of the Shiite Fatimids. The year 909 saw the overthrow of the Sunni Aghlabites who ruled Ifriqiya and the establishment of the Fatimid dynasty. During the rule of the Fatimids, Kairouan was neglected and lost its importance: the new rulers resided first in Raqqada but soon moved their capital to the newly built Al Mahdiyah on the coast of modern Tunisia. After succeeding in extending their rule over all of central Maghreb, an area consisting of the modern countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, they eventually moved east to Egypt to found Cairo making it the capital of their vast Caliphate and leaving the Zirids as their vassals in Ifriqiya. Governing again from Kairouan, the Zirids led the country through another artistic, commercial and agricultural heyday. Schools and universities flourished, overseas trade in local manufactures and farm produce ran high and the courts of the Zirids rulers were centres of refinement that eclipsed those of their European contemporaries. When the Zirids declared their independence from Cairo and their conversion to Sunni Islam in 1045 by giving allegiance to Baghdad, the Fatimid Caliph Ma'ad al-Mustansir Billah sent as punishment hordes of troublesome Arab tribes (Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym) to invade Ifriqiya. These invaders so utterly destroyed Kairouan in 1057 that it never regained its former importance and their influx was a major factor in the spread of nomadism in areas where agriculture had previously been dominant. Some 1,700 years of intermittent but continual progress was undone within a decade as in most part of the country the land was laid to waste for nearly two centuries. In the 13th century under the prosperous Hafsids dynasty that ruled Ifriqiya, the city started to emerge from its ruins. It is only under the Husainid Dynasty that Kairouan started to find an honorable place in the country and throughout the Islamic world. In 1881, Kairouan was taken by the French, after which non-Muslims were allowed access to the city. The French built the 600 mm (1 ft 11 5⁄8 in) Sousse–Kairouan Decauville railway, which operated from 1882 to 1996, before it was regauged to 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge.

Jews

Jews were among the original settlers of Kairouan, and the community played an important role in Jewish history, having been a world center of Talmudic and Halakhic scholarship for at least three generations.[10]

Climate

Kairouan has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh).

| Climate data for Kairouan (1981–2010, extremes 1901–2017) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30.0 (86.0) |

37.3 (99.1) |

39.2 (102.6) |

37.8 (100.0) |

44.6 (112.3) |

48.0 (118.4) |

47.9 (118.2) |

48.1 (118.6) |

45.0 (113.0) |

41.3 (106.3) |

36.0 (96.8) |

30.9 (87.6) |

48.1 (118.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.2 (63.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

29.2 (84.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

37.7 (99.9) |

37.5 (99.5) |

32.5 (90.5) |

27.8 (82.0) |

22.2 (72.0) |

18.3 (64.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.5 (52.7) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.5 (63.5) |

21.8 (71.2) |

26.2 (79.2) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

25.7 (78.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

20.0 (68.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

7.3 (45.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

11.7 (53.1) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

11.7 (53.1) |

8.2 (46.8) |

14.3 (57.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.5 (23.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.0 (46.4) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 28.7 (1.13) |

19.1 (0.75) |

28.1 (1.11) |

26.6 (1.05) |

22.8 (0.90) |

8.0 (0.31) |

2.0 (0.08) |

11.4 (0.45) |

44.2 (1.74) |

41.6 (1.64) |

28.3 (1.11) |

29.0 (1.14) |

289.8 (11.41) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 3.5 | 3.7 | 4.9 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 37.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 64 | 62 | 62 | 61 | 58 | 53 | 49 | 53 | 59 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 60 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 186.0 | 190.4 | 226.3 | 252.0 | 300.7 | 324.0 | 362.7 | 334.8 | 270.0 | 235.6 | 207.0 | 186.0 | 3,075.5 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.0 | 6.8 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 9.7 | 10.8 | 11.7 | 10.8 | 9.0 | 7.6 | 6.9 | 6.0 | 8.4 |

| Source 1: Institut National de la Météorologie (precipitation days/humidity/sun 1961–1990, extremes 1951–2017)[11][12][13][note 1] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (humidity and sun 1961–1990),[15] Deutscher Wetterdienst (extremes, 1901–1990)[16] | |||||||||||||

Religion

The most important mosque in the city is the Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba (Uqba ibn nafée) also known as the Great Mosque of Kairouan. It has been said that seven pilgrimages to this mosque is considered the equivalent of one pilgrimage to Mecca.[17] After its establishment, Kairouan became an Islamic and Qur'anic learning centre in North Africa. An article by Professor Kwesi Prah describes how during the medieval period, Kairouan was considered the fourth holiest city in Islam after Mecca, Medina and Jerusalem;[18] this tradition is said to continue into the present day.[19]

In memory of Sufi saints, Sufi festivals are held in the city.[20]

At the time of its greatest splendor, between the ninth and eleventh centuries AD, Kairouan was one of the greatest centers of Islamic civilization and its reputation as a hotbed of scholarship covered the entire Maghreb. During this period, the Great Mosque of Kairouan was both a place of prayer and a center for teaching Islamic sciences under the Maliki current. One may conceivably compare its role to that of the University of Paris during the Middle Ages.[21]

In addition to studies on the deepening of religious thought and Maliki jurisprudence, the mosque also hosted various courses in secular subjects such as mathematics, astronomy, medicine and botany. The transmission of knowledge was assured by prominent scholars and theologians which included Sahnun ibn Sa'id and Asad ibn al-Furat, eminent jurists who contributed greatly to the dissemination of the Maliki thought, Ishaq ibn Imran and Ibn al-Jazzar in medicine, Abu Sahl al-Kairouani and Abd al-Monim al-Kindi in mathematics. Thus the mosque, headquarters of a prestigious university with a large library containing many scientific and theological works, was the most remarkable intellectual and cultural center in North Africa during the ninth, tenth and eleventh centuries.

A unique religious tradition in Kairouan was the use of Islamic law to enforce monogamy by stipulating it in the marriage contract, a practice common among both elites and commoners. This stipulation gave a woman legal recourse in the case that her husband sought to take a second wife. Although the introduction of the 1956 Code of Personal Status rendered the tradition obsolete by outlawing polygamy nationwide, some scholars have identified it as a "positive tradition for women within the large framework of Islamic law."[22]

Main sights

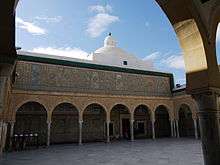

Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba

The city's main attraction is the Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba, which is said to largely consist of its original building materials. In fact most of the column stems and capitals were taken from ruins of earlier-period buildings, while others were produced locally. There are 414 marble, granite and porphyry columns in the mosque. Almost all were taken from the ruins of Carthage. Previously, it was forbidden to count them, on pain of blinding.[23] The Great Mosque of Kairouan (Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba) is considered as one of the most important monuments of Islamic civilization as well as a worldwide architectural masterpiece.[24] Founded by Arab general Uqba Ibn Nafi in 670 CE, the present aspect of the mosque dates from the 9th century.[25] The Great Mosque of Sidi-Uqba has a great historical importance as the ancestor of all the mosques in the western Islamic world.[26]

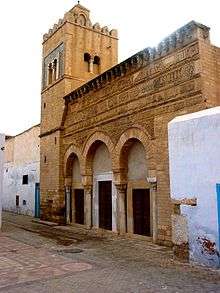

Mosque of the Three Gates

The Mosque of the Three Gates was founded in 866. Its façade is a notable example of Islamic architecture.[27] It has three arched doorways surmounted by three inscriptions in Kufic script, interspersed with floral and geometrical reliefs and topped by a carved frieze; the first inscription includes the verses 70–71 in the sura 33 of Quran.[28] The small minaret was added during the restoration works held under the Hafsid dynasty. The prayer hall has a nave and two aisles, divided by arched columns, parallel to the qibla wall.

Mosque of the Barber

The Mausoleum of Sidi Sahab, generally known as the Mosque of the Barber, is actually a zaouia located inside the city walls. It was built by the Muradid Hammuda Pasha Bey (mausoleum, dome and court) and Murad II Bey (minaret and madrasa). In its present state, the monument dates from the 17th century.[29]

The mosque is a veneration place for Abu Zama' al-Balaui, a companion of the prophet Muhammad, who, according to a legend, had saved for himself three hairs of Muhammad's beard, hence the edifice's name.[30] The sepulchre place is accessed from a cloister-like court with richly decorated ceramics and stuccoes.

Other buildings

Kairouan is also home to:

- two large water reservoirs called "Aghlabid basins"

- Mosque of Ansar (traditionally dating to 667, but totally renewed in 1650)

- Mosque Al Bey (late 17th century)

- The souk (market place), in the Medina quarter, which is surrounded by walls, from which the entrance gates can be seen in the distance. Products that are sold in the souk include carpets, vases and goods made of leather.

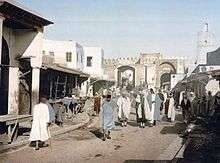

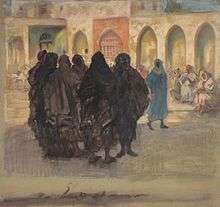

Street scene

Street scene Bread vendor

Bread vendor Inside the Medina

Inside the Medina

In popular culture

Kairouan was used as a filming location for the 1981 film Raiders of the Lost Ark, standing in for Cairo. As the film is set in 1936, television antennas throughout the city were taken down for the duration of filming.

Twin towns

|

See also

References

- Nagendra Kr Singh, International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties. Anmol Publications PVT. LTD. 2002. page 1006

- Luscombe, David; Riley-Smith, Jonathan, eds. (2004). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2; Volume 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 696. ISBN 9780521414111.

- Europa Publications "General Survey: Holy Places" The Middle East and North Africa 2003, p. 147. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 1-85743-132-4. "The city is regarded as a holy place for Muslims."

- Hutchinson Encyclopedia 1996 Edition. Helicon Publishing Ltd, Oxford. 1996. p. 572. ISBN 1-85986-107-5.

- "Location and origin of the name of Kairouan". Isesco.org. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "قيروان" Archived 1 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Dehkhoda Dictionary.

- «رابطه دو سویه زبان فارسی–عربی». ماهنامه کیهان فرهنگی. دی 1383، شماره 219. صص 73–77.

- Conant, Jonathan (2012). Staying Roman : conquest and identity in Africa and the Mediterranean, 439–700. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 280–281. ISBN 0521196973.

- Barbara M. Kreutz, Before the Normans: Southern Italy in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1996, p. 48

- Kairouan Jewish Encyclopedia (1906)

- "Les normales climatiques en Tunisie entre 1981 2010" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 19 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Données normales climatiques 1961-1990" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Les extrêmes climatiques en Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Réseau des stations météorologiques synoptiques de la Tunisie" (in French). Ministère du Transport. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- "Kairouan Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Klimatafel von Kairouan / Tunesien" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961-1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- The Middle East and North Africa. Europa Publications Limited. 30 October 2003. p. 150. ISBN 978-1-85743-184-1. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- Professor Prah, founder and Director of the Centre for Advanced Study of African Societies (11–12 May 2004), Towards a Strategic Geopolitic Vision of Afro-Arab Relations, AU Headquarters, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia,

By 670, the Arabs had taken Tunisia, and by 675, they had completed construction of Kairouan, the city that would become the premier Arab base in North Africa. Kairouan was later to become the third holiest city in Islam in the medieval period, after Mecca and Medina, because of its importance as the centre of the Islamic faith in the Maghrib.

Paper submitted to the African Union (AU) Experts’ Meeting on a Strategic Geopolitic Vision of Afro-Arab Relations - Dr. Ray Harris; Khalid Koser (30 August 2004). Continuity and change in the Tunisian sahel. Ashgate. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-7546-3373-0. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- "Tunisia News – Sufi Song Festival starts in Kairouan". News.marweb.com. 25 February 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Henri Saladin (1908), Tunis et Kairouan (in French) (Henri Laurens ed.), Paris, p. 118

- Largueche, Dalenda (2010). "Monogamy in Islam: The Case of a Tunisian Marriage Contract" (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IAS School of Social Science.

- Mooney, Julie (2004). Ripley's Believe It or Not! Encyclopedia of the Bizarre: Amazing, Strange, Inexplicable, Weird and All True!. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. p. 47. ISBN 1-57912-399-6.

- "The Great Mosque of Kairouan". Kairouan.org. Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- "Great Mosque of Kairouan (Qantara mediterranean heritage)". Qantara-med.org. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- John Stothoff Badeau and John Richard Hayes, ''The Genius of Arab civilization: source of Renaissance''. Taylor & Francis. 1983. p. 104. Books.google.fr. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- Saladin, Henri (1908). Tunis et Kairouan. Voyages à travers l'architecture, l'artisanat et les mœurs du début du XXe siècle. Paris: Henri Laurens.

- Kircher, Gisela (1970). Die Moschee des Muhammad b. Hairun (Drei-Tore-Moschee) in Qairawân/Tunesien. 26. Cairo: Publications de l'Institut archéologique allemand. pp. 141–167.

- Mausoleum of Sidi Sahbi (Qantara Mediterranean heritage) Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- K. A. Berney and Trudy Ring, International dictionary of historic places: Middle East and Africa, Volume 4. Taylor & Francis. 1996. p. 391

- "Kardeş Şehirler". Bursa Büyükşehir Belediyesi Basın Koordinasyon Merkez. Tüm Hakları Saklıdır. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

Notes

- The Station ID for Kairouan is 33535111.[14]

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Kairouan. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kairouan. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Kairwan. |

- Official website

- Kairouan, tourismtunisia.com

- Kairouan World heritage Site, whc.unesco.org

- Kairouan University

- Al-Qayrawan, muslimheritage.com

- Kairwan, jewishencyclopedia.com

- WorldStatesmen-Tunisia

- KAIROUAN, The Capital of Islamic Culture

- Panoramic virtual tour of Kairouan medina