Python (genus)

Python is a genus of constricting snakes in the Pythonidae family native to the tropics and subtropics of the Eastern Hemisphere.[1]

| Python | |

|---|---|

| |

| Burmese python (Python bivittatus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Suborder: | Serpentes |

| Family: | Pythonidae |

| Genus: | Python Daudin, 1803 |

| Synonyms | |

|

List

| |

The name Python was proposed by François Marie Daudin in 1803 for non-venomous flecked snakes.[2] Currently, 10 python species are recognized as valid taxa.[3]

Three formerly considered python subspecies have been promoted, and a new species recognized.

Taxonomy

The generic name Python was proposed by François Marie Daudin in 1803 for non-venomous snakes with a flecked skin and a long split tongue.[2]

In 1993, seven python species were recognized as valid taxa.[4] Based on phylogenetic analyses, between seven and 13 python species are recognized.[5][6]

| Species | Image | IUCN Red List and geographic range |

|---|---|---|

| Indian python (P. molurus) (Linnaeus, 1758)[7] |  |

NE

|

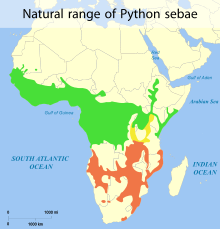

African rock python (P. sebae) (Gmelin, 1788)[8]

|

NE

| |

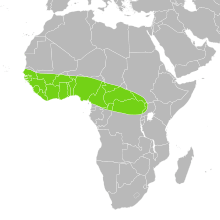

| Ball python (P. regius) (Shaw, 1802)[9] | .jpg) |

LC[10]

|

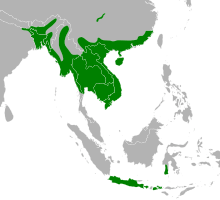

| Burmese python (P. bivittatus) (Kuhl, 1820)[11] | .jpg) |

VU[12]

|

| Sumatran short-tailed python (P. curtus) (Schlegel, 1872)[13] | .jpg) |

LC[14] Southeast Asia in southern Thailand, Malaysia (Peninsular and Sarawak) (including Pinang) and Indonesia (Sumatra, Riau Archipelago, Lingga Islands, Bangka Islands, Mentawai Islands and Kalimantan).[14] |

| Bornean short-tailed python (P. breitensteini) (Steindachner, 1881)[15] | .jpg) |

LC[16] |

| Angolan python (P. anchietae) (Bocage, 1887) | .jpg) |

LC[17] |

| Brongersma's short-tailed python (P. brongersmai) (Stull, 1938) (formerly P. curtus brongersmai) |  |

LC[18] Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Bangka Island, Lingga islands, Riau islands, and Pinang[18] |

| Myanmar short-tailed python (P. kyaiktiyo) (Zug, Gotte & Jacobs, 2011)[19] |  |

VU[20] |

| Python europaeus (Szyndlar & Rage, 2003)[21] | EX Extinct species from the Miocene era, described on basis of vertebrae found in Vieux-Collonges and La Grive in France.[21] |

Distribution and habitat

In Africa, pythons are native to the tropics south of the Sahara, but not in the extreme south-western tip of southern Africa (Western Cape) or in Madagascar. In Asia, they occur from Bangladesh, Nepal, India, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, including the Nicobar Islands, through Myanmar, east to Indochina, southern China, Hong Kong and Hainan, as well as in the Malayan region of Indonesia and the Philippines.[1]

Invasive

Some suggest that P. bivittatus and P. sebae have the potential to be problematic invasive species in South Florida.[22] In early 2016, after a culling operation yielded 106 pythons, Everglades National Park officials suggested that "thousands" may live within the park, and that the species has been breeding there for some years. More recent data suggest that these pythons would not withstand winter climates north of Florida, contradicting previous research suggesting a more significant geographic potential range.[23]

Uses

Python skin is used to make clothing, such as vests, belts, boots and shoes, or fashion accessories such as handbags. It may also be stretched and formed as the sound board of some string musical instruments, such as the erhu spike-fiddle, sanxian and the sanshin lutes.[24][25]

As pets

Many Python species, such as P. regius, P. brongersmai, P. bivittatus and M. reticulatus[26], are popular to keep as pets due to their ease of care, docile temperament, and vibrant colors, with some rare mutations having been sold for several thousands of dollars. Despite controversy that has arisen from media reports, with proper safety procedures pet pythons are relatively safe to own,[27] and deaths associated with them are isolated compared to other domestic animals, such as dogs and horses.[25][28]

Etymology

The word 'python' is derived from the Latin word 'pȳthon' and the Greek word 'πύθων', both referring to the "serpent slain, who was fabled to have been called Pythius in commemoration of his victory near Delphi by Apollo according to the myth".[29]

References

- McDiarmid, R. W.; Campbell, J. A.; Touré, T. (1999). "Python". Snake Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Volume 1. Washington, DC: Herpetologists' League. ISBN 1893777014.

- Daudin, F. M. (1803). "Python". Histoire naturelle, générale et particulière, des reptiles. Tome 8. Paris: De l'Imprimerie de F. Dufart. p. 384.

- Barker, D. G.; Barker, T. M.; Davis, M. A.; Schuett, G. W. (2015). "A review of the systematics and taxonomy of Pythonidae: an ancient serpent lineage" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 175 (1): 1−19. doi:10.1111/zoj.12267.

- Kluge, A. G. (1993). "Aspidites and the phylogeny of pythonine snakes". Records of the Australian Museum (Supplement 19): 1–77.

- Lawson, R.; Slowinski, J. B.; Burbrink, F. T. (2004). "A molecular approach to discerning the phylogenetic placement of the enigmatic snake Xenophidion schaeferi among the Alethinophidia". Journal of Zoology. 263: 285–294. doi:10.1017/s0952836904005278.

- Reynolds, R. G.; Niemiller, M. L.; Revell, L. J. (2014). "Toward a tree-of-life for the boas and pythons: multilocus species-level phylogeny with unprecedented taxon sampling". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (71): 201–213.

- Linnaeus, C. (1758). "Coluber molurus". Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (Tenth reformed ed.). Holmiae: Laurentii Salvii. p. 225.

- Gmelin, J. F. (1788). "Coluber sebae". Caroli a Linné. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae: secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. I, Part III (13., aucta, reformata ed.). Lipsiae: Georg Emanuel Beer. p. 1118.

- Shaw, G. (1802). "Royal Boa". General zoology, or Systematic natural history. Volume III, Part II. London: G. Kearsley. pp. 347–348.

- Auliya, M.; Schmitz, A. (2010). "Python regius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2010: e.T177562A7457411. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T177562A7457411.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Kuhl, H. (1820). "Python bivittatus mihi". Beiträge zur Zoologie und vergleichenden Anatomie. Frankfurt am Main: Verlag der Hermannschen Buchhandlung. p. 94.

- Stuart, B.; Nguyen, T. Q.; Thy, N.; Grismer, L.; Chan-Ard, T.; Iskandar, D.; Golynsky, E. & Lau, M. W. N. (2012). "Python bivittatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T193451A2237271. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T193451A2237271.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Schlegel, H. (1872). "De Pythons". In Witkamp, P. H. (ed.). De Diergaarde van het Koninklijk Zoölogisch Genootschap Natura Artis Magistra te Amsterdam: De Kruipende Dieren. Amsterdam: Van Es. pp. 53–54.

- Inger, R. F.; Iskandar, D.; Lilley, R.; Jenkins, H.; Das, I. (2014). "Python curtus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2014: e.T192244A2060581. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T192244A2060581.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Steindachner, F. (1880). "Über eine neue Pythonart (Python breitensteini) aus Borneo". Sitzungsberichte der Kaiserlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften Wien. 82: 267−280.

- Inger, R. F.; Iskandar, D.; Lilley, R.; Jenkins, H.; Das, I. (2012). "Python breitensteini". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012: e.T192013A2028005. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T192013A2028005.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Auliya, M. (2010). "Python anchietae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2010: e.T177539A7452448. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2010-4.RLTS.T177539A7452448.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Grismer, L.; Chan-Ard, T. (2012). "Python brongersmai". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2012: e.T192169A2050353. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T192169A2050353.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Zug, G. R.; Gotte, S. W.; Jacobs, J. F. (2011). "Pythons in Burma: Short-tailed python (Reptilia: Squamata)" (PDF). Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 124 (2): 112−136. doi:10.2988/10-34.1.

- Wogan, G.; Chan-Ard, T. (2012). "Python kyaiktiyo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2012: e.T199854A2614411. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T199854A2614411.en. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- Szyndlar, Z.; Rage, J. C. (2003). "Python europaeus". Non-erycine Booidea from the Oligocene and Miocene of Europe. Kraków: Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals. pp. 68−72.

- "Python Snakes, An Invasive Species In Florida, Could Spread To One Third Of US". ScienceDaily. 2008. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- Avery, M. L.; Engeman, R. M.; Keacher, K. L.; Humphrey, J. S.; Bruce, W. E.; Mathies, T. C.; Mauldin, R. E. (2010). "Cold weather and the potential range of invasive Burmese pythons". Biological Invasions. 12 (11): 3649−3652. doi:10.1007/s10530-010-9761-4.

- http://erhuworld.com/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-21. Retrieved 2015-04-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://reptile-database.reptarium.cz/species?genus=Malayopython&species=reticulatus

- "Playing with the Big Boys: Handling Large Constrictors". www.anapsid.org. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- "Untitled Document". www.anapsid.org. Retrieved 2017-08-01.

- Lewis, C. T.; Short, C. (1879). "Pȳthon". A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Python (genus) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Python (genus). |

- Python at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 11 September 2007.