Puntofijo Pact

The Puntofijo Pact was a formal arrangement arrived at between representatives of Venezuela's three main political parties in 1958, Acción Democrática (AD), COPEI (Social Christian Party), and Unión Republicana Democrática (URD), for the acceptance of the 1958 presidential elections, and the preservation of the new democratic system. This pact was a written guarantee that the signing parties would respect the election results, prevent single-party hegemony, work together to fight dictatorship, as well as an agreement to share oil wealth.[1]

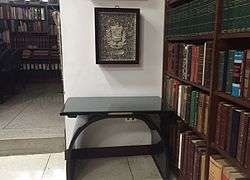

Table where the Puntofijo Pact was signed on 31 October 1958 in Caracas, Venezuela. | |

| Signed | 31 October 1958 |

|---|---|

| Location | Puntofijo Residence, Francisco Solano López Avenue, Sabana Grande, Caracas, Venezuela |

| Parties |

|

The pact is often credited with launching Venezuela towards democracy, being recognized for creating the most stable period in the history of Venezuela's republics.[2][3] While the pact did provide the grounds for possible democratic deepening, it has also been criticized for starting a bipartisanship period between AD and COPEI.[4]

Background

On January 23, 1958, President Marcos Pérez Jiménez fled Venezuela for the Dominican Republic and a group of military leaders took control of the country.[5] The presidency of Pérez Jiménez was a dictatorship that relied heavily on oil revenues to pay for a massive urbanization and modernization campaign in the cities of Venezuela.[5] The United States supported the government of Venezuela because it was a reliable oil source.

Following Pérez Jiménez's ouster, the three major parties in the country — COPEI, AD, and the URD — came together to ensure a lasting democracy in Venezuela, a country that had been under dictatorial rule for nearly all of its history since gaining independence in 1830.

The parties were aware that if one of them disputed the results of the pending election, it would only harm the country given the economic instability and volatility that had resulted from the declining oil prices and post-coup atmosphere. The pact was a way for the parties to ensure cooperation and compliance with election results. This would allow for the transition to democracy.

Signing and Results

The pact was signed in, and named after, the residence of COPEI leader Rafael Caldera in Caracas, by representatives of the URD, COPEI, and AD. Its adherents claimed the pact was aimed at preserving Venezuelan democracy by respecting elections, by having the winners of the elections consider including members of the signing parties and others in positions of power in bids for national unity governments, and by having a basic shared program of government.[1] They guaranteed, for example, the continuation of obligatory military service; improved salaries, housing, and equipment for the military; and, most important, amnesty from prosecution for crimes committed during the dictatorship.

Three members of each party signed the pact. These men included Rómulo Betancourt of AD, Rafael Caldera of COPEI, and Jóvito Villalba of the URD.[6] Both Betancourt and Caldera would go on to become presidents of Venezuela. The pact served to deepen democracy in the region in that it ensured respect of the democratic process of the election. This allowed for the uncontested democratic election of Rómulo Betancourt.

According to others, the pact bound the parties to limit Venezuela's political system to an exclusive competition between two parties.[7] The creation of the pact meant that no matter which political group won the election, the others would share in the power. This formed a coalition style government that essentially centered power in the hands of COPEI and AD.[8] This led to later deterioration as COPEI and AD became increasingly reliant on the shared oil revenues to secure their power over Venezuelan politics using a vast system of patronage and clientelism.[9] This would later be called "partyarchy" given the amount of control that the two political parties exercised in Venezuelan politics.

Opposition

When the pact was first signed there was little opposition with the exception of some journalists and leftists, who objected to the pact's exclusion of the Communist Party.[10] They saw that exclusion as denial of any leftist participation or the more radical reforms they had hoped for when Pérez Jiménez was ousted.

Eventually, the pact became a power-sharing agreement between the two main political parties (Copei and AD). Citizens, intellectuals, journalists, and the media started to demand reform of the whole political system to fit a growing democratic society. More formal opposition emerged in the late 1980s. One of the first indicators of public unrest was on February 27, 1989 where there were riots due to an increase in the prices of public transportation and gas.[11] The 1993 presidential elections brought the first break from the pact; the former leader of COPEI, Rafael Caldera, was elected president under a different party, Convergencia.[11] These events signified rising public dissatisfaction with the political system that the Pact of Puntofijo had created.

Deterioration

The system of patronage and monopoly of power held by AD and COPEI began to deteriorate in the 1980s as oil revenues took a sharp decline.[4] This led to increasing public distrust of the legitimacy of the AD and COPEI. What began as democratic deepening began to deteriorate. The power granted to the AD and COPEI through the pact allowed them to institutionalize the ideals of the pact into the constitution of 1961.[8] This allowed for the AD and COPEI to exclude other political parties due to the strength the pact and oil revenues supplied. The Constitution of 1961 gave the president the power to "control the nation's defense, the monetary system, all tax and tariff policy, the exploitation of subsoil rights, the management of foreign affairs, and a variety of other powers. It had the authority to name all cabinet ministers, state governors, and state enterprise officials".[9] This is most noted in the exclusion of leftist parties like the Communist Party of Venezuela (PCV) in the pact itself. As oil revenues began to decrease, the AD and COPEI began to increasingly resort to violence to maintain support as the public began to question the legitimacy of their control on power. Oil revenues had provided the funds to pay off those who would otherwise oppose the parties. Without those funds, the AD and COPEI were unable to sustain their power without reverting to violent oppression of its rivals. This drew public outrage for the pact.

Under Chávez

The Pact of Puntofijo continued to play a role in Venezuelan politics forty years later as Hugo Chávez sought the presidency. Former Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez promised in his 1998 presidential campaign that he would break the old system and open up political power to independent and third parties.[12] Chávez ran on a platform of condemning the acts of AD and COPEI and their monopoly of power which became known as partyarchy. Chávez considered the pact to be "synonymous with elitist rule".[11] The Pact of Puntofijo had institutionalized a system of patronage that allowed the AD and COPEI to fully embed themselves in the political system of Venezuela. Chávez believed that they had created a government that was no longer reflective of its citizens and that the two parties had prevented political participation. Increasing public distrust of the political parties led to a referendum prohibiting parties from participating in the 1999 presidential election.[13] This inherently solidified Chávez’s rise to power. The people offered overwhelming support for the break from the traditional pact run government.

Similar pacts

It bore a resemblance to the turno pacifico of the restored Spanish monarchy between 1876 and 1923, in which Conservative and Liberal Parties alternated in power.

The Miami Pact signed in Cuba in 1957 is also similar to that of Puntofijo. It was also a political agreement between parties that was designed to confront dictatorship (Batista's regime), uphold democracy, as well as invite political participation.[13] Though ultimately the Miami Pact failed to fulfill its duties as a democratic deepener due to struggles in the alliance between the signers. The National Front (Colombia) was another contemporary agreement.

See also

References

- Corrales, Javier (2001-01-01). "Strong Societies, Weak Parties: Regime Change in Cuba and Venezuela in the 1950s and Today". Latin American Politics and Society. 43 (2): 81–113. doi:10.2307/3176972. JSTOR 3176972.

- Rey, J. C. (1991). La Democracia Venezolana y la crisis del sistema populista de conciliacion. pp. 533–578.

- Philip, G. (2003). Democracy in Latin America: Surviving conflict and crisis?. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- McCoy, Jennifer (July 1999). "Chavez and the End of "Partyarchy" in Venezuela". Journal of Democracy. 10 (3): 64–77. doi:10.1353/jod.1999.0049. ISSN 1086-3214.

- Velasco, Alejandro (2015). Barrio Rising.

- "Document #22: "Pact of Puntofijo," Acción Democrática, COPEI and Unión Republicana Democrática (1958) | Modern Latin America". library.brown.edu. Retrieved 2016-11-27.

- Kozloff, Nikolas (2007). Hugo Chávez: Oil, Politics, and the Challenge to the U.S. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 61. ISBN 9781403984098.

- Karl, Terry Lynn (1987-01-01). "Petroleum and Political Pacts: The Transition to Democracy in Venezuela". Latin American Research Review. 22 (1): 63–94. JSTOR 2503543.

- Buxton, Julia (2005-07-01). "Venezuela's Contemporary Political Crisis in Historical Context". Bulletin of Latin American Research. 24 (3): 328–347. doi:10.1111/j.0261-3050.2005.00138.x. ISSN 1470-9856.

- Rich, Michael Glenn (2001). Democracy, Journalism, and the Press: Venezuela in 1958. The University of Iowa.

- Ellner, Steve (2000). "Polarized Politics Chávez's Venezuela". NACLA Report on the Americas. 33 (6): 29–42. doi:10.1080/10714839.2000.11725610.

- Ellner, Steve, Hellinger, Daniel (2004). Venezuelan Politics in the Chávez Era: Class, Polarization, and Conflict. Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 9781588262974.

- Cameron, Maxwell A. (2003-01-01). "Strengthening checks and balances: Democracy defence and promotion in the Americas". Canadian Foreign Policy Journal. 10 (3): 101–116. doi:10.1080/11926422.2003.9673346. ISSN 1192-6422.

External links

- Pacto de Puntofijo, in Spanish.