Energy policy of Venezuela

Venezuela has the largest conventional oil reserves and the second-largest natural gas reserves in the Western Hemisphere.[1] In addition Venezuela has non-conventional oil deposits (extra-heavy crude oil, bitumen and tar sands) approximately equal to the world's reserves of conventional oil.[2] Venezuela is also amongst world leaders in hydroelectric production, supplying a majority of the nation's electrical power through the process.

Development of energy policies

Venezuela nationalized its oil industry in 1975–1976, creating Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PdVSA), the country's state-run oil and natural gas company. Along with being Venezuela's largest employer, PdVSA accounts for about one-third of the country's GDP, 50% of the government's revenue and 80% of Venezuela's exports earnings.

The policy changed in the 1990s, when Venezuela introduced a new oil policy known as Apertura Petrolera, which opened its upstream oil sector to private investments. This facilitated the creation of 32 operating service agreements with 22 separate foreign oil companies, including international oil majors like Chevron, BP, Total, and Repsol-YPF. The role of PdVSA in making national oil policy increased significantly.[3] In 1999, Venezuela adopted the Gas Hydrocarbons Law, which opened all aspects of the sector to private investment.[4]

This policy changed after Hugo Chávez took the presidential post in 1999. In recent years the Venezuelan government has reduced PdVSA's previous autonomy and amended the rules regulating the country's hydrocarbons sector. In 2001, Venezuela passed a new Hydrocarbons Law that superseded the previous 1943 Hydrocarbons Law and 1975 Nationalization Law. Under the 2001 law, royalties paid by private companies increased from 1-17% to 20-30%.[4] Venezuela started to strictly adhere to OPEC production quotas. The ownership separation of power generation, transmission, distribution and supply functions was required by 2003 but still not enforced.

Venezuela's new energy policy implemented by President Chávez in 2005 includes six major projects:

- Magna Reserve;

- Orinoco Project;

- Delta-Caribbean Project;

- Refining Project;

- Infrastructure Project;

- Integration Project.[5]

In 2007, Chávez announced the nationalization of the oil industry.[6] The foreign oil companies were forced to sign agreements giving majority control of hydrocarbons projects to PdVSA. Projects owned by companies like ConocoPhillips and ExxonMobil, who failed to sign these agreements, were taken over by PdVSA.[7]

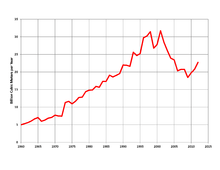

Venezuela's oil production has fallen by a quarter since President Chávez took office and falling oil prices have affected the government budget severely.[8] However, since 2009, oil prices have surged, and more nations around the world are turning to Venezuela's large oil reserves to boost tight energy supplies: Italy's Eni SpA, Petrovietnam and Japanese companies including Itochu Corp. and Marubeni Corp. have signed on to, or are in negotiations to sign on to, joint-ventures with PdVSA.[9] China National Petroleum Corp., or CNPC, also signed a $16.3 billion joint-venture agreement for a project that will eventually pump an additional 1 million barrels per day (160,000 m3/d) for Asian refineries. Separately, Venezuela has been exporting 200,000 barrels per day (32,000 m3/d) of crude to China to repay $20 billion of loans extended by the China Development Bank Corp. in April 2010 to finance much-needed infrastructure projects in Venezuela.[9] PdVSA is selling oil at market prices to repay the 10-year loan. Shipments to repay the debt represent half Venezuela's daily crude exports to China.[9]

Primary energy sources

Oil

Venezuela has been producing oil for nearly a century and was an OPEC founder-member. In 2005, Venezuela produced 162 million tons of oil, which is 4.1% of world's total production. By the oil production Venezuela ranks seventh in the world.[10] Venezuela is the world's eight oil exporter and fifth largest net exporter.[10] In 2012, 11 percent of US oil imports came from Venezuela.[11]

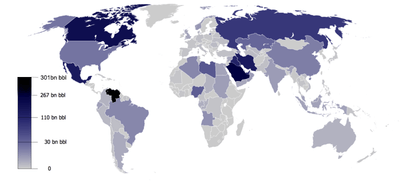

Since 2010, when the heavy oil from the Orinoco Belt was considered to be economically recoverable, Venezuela has had the largest proved reserves of petroleum in the world, about 298 billion barrels.[12]

Oil accounts for about half of total government revenues. The leading oil company is Petróleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA), which according to Venezuelan authorities produces 3.3 million barrels per day (520,000 m3/d).[1] However, oil industry analysts and the U.S. Energy Information Administration believe it to be only 2.8-2.9 million barrels per day (460,000 m3/d). Venezuela's main oil fields are located at four major sedimentary basins: Maracaibo, Falcon, Apure, and Oriental. PdVSA has 1.28 million barrels per day (204,000 m3/d) of crude oil refining capacity. The major facilities are the Paraguaná Refining Center, Puerto de la Cruz, and El Palito.[4]

Natural gas

.svg.png)

As of 2013, Venezuela has the eighth-largest proved natural gas reserves in the world and the largest in South America. Proved reserves were estimated at 5.5 trillion cubic meters (tcm).[13] However, inadequate transportation and distribution infrastructure has prevented it from making the most of its resources. More than 70% of domestic gas production is consumed by the petroleum industry.[1] Nearly 35% of gross natural gas output are re-injected in order to boost or maintain reservoir pressures, while smaller amounts (5%) are vented or flared. About 10% of production volumes are subject to shrinkage as a result of the extraction of NGLs.[14] The 2010 estimate is 176 trillion cubic feet (5,000 km3), and the nation reportedly produced about 848 billion cubic feet (2.40×1010 m3) in 2008.[15]

The leading gas company is PdVSA. The largest private natural gas producer is Repsol-YPF, who supplies 80-megawatt (MW) power station in Portuguesa, and plans to develop a 450-MW power plant in Obispos.[4]

Tar sands and heavy oils

Venezuela has non-conventional oil deposits (extra-heavy crude oil, bitumen and tar sands) at 1,200 billion barrels (1.9×1011 m3) approximately equal to the world's reserves of conventional oil. About 267 billion barrels (4.24×1010 m3) of this may be producible at current prices using current technology.[2] The main deposits are located in the Orinoco Belt in central Venezuela (Orinoco tar sands), some deposits are also found in the Maracaibo Basin and Lake Guanoco, near the Caribbean coast.[14]

Coal

Venezuela has recoverable coal reserves of approximately 528 million short tons (Mmst), most of which is bituminous. Coal production was at 9.254 million short tons as of 2007.[16] Most coal exports go to Latin American countries, the United States and Europe.[4]

The main coal company in Venezuelas is Carbozulia, a former subsidiary of PdVSA, which is controlled by Venezuela's state development agency Corpozulia. The major coal-producing region in Venezuela is the Guasare Basin, which is located near the Colombian border. The coal industry development plans include the construction of a railway linking coal mines to the coast and a new deepwater port.[4]

Electricity

The main electricity source is hydropower, which accounts for 71% in 2004.[10] A gross theoretical capability of hydropower is 320 TWh per annum, of which 130 TWh per annum is considered as economically feasible.[14] In 2004, Venezuela produced 70 TWh of hydropower, which accounts 2.5% of world's total.[10] At the end of 2002, total installed hydroelectric generating capacity accounted 13.76 GW with additional 4.5 GW under construction and 7.4 GW of planned capacity.[14]

Hydroelectricity production is concentrated on the Caroní River in Guayana Region. Today it has 4 different dams. The largest hydroplant is the Guri dam with 10,200 MW of installed capacity, which makes it the third-largest hydroelectric plant in the world.[1] Other facilities on the Caroní are Caruachi, Macagua I, Macagua II and Macagua III, with a total of 15.910 MW of installed capacity in 2003. New dams, Tocoma (2 160 MW) and Tayucay (2 450 MW), are currently under construction between Guri and Caruachi. With a projected installed capacity for the whole Hydroelectric Complex (upstream Caroni River and downstream Caroni River), between 17.250 and 20.000 MW in 2010.

The largest power companies are state-owned CVG Electrificación del Caroní (EDELCA), a subsidiary of the mining company Corporación Venezolana de Guayana (CVG), and Compania Anonima de Administracion y Fomento Electrico (CADAFE) accounting respectively for approximately 63% and 18% of generating capacities. Other state-owned power companies are ENELBAR and ENELVEN-ENELCO (approximately 8% of capacities). In 2007, PDVSA bought 82.14% percent of Electricidad de Caracas (EDC) from AES Corporation as part of a renationalization program. Subsequently, the ownership share rose to 93.62% (December 2008).[17] EDC has 11% of Venezuelan capacity, and owns the majority of conventional thermal power plants.[18][19] The rest of the power production is owned by private companies.

The national transmission system (Sistema Inrterconectado Nacional- SIN) is composed by four interconnected regional transmission systems operated by EDELCA, CADAFE, EDC and ENELVEN-ENELCO. Oficina de Operacion de Sistema Interconectados (OPSIS), jointly owned by the four vertical integrated electric companies, operate the SIN under an RTPA regime.[18]

Environmental issues

Prolonged oil production has resulted in significant oil pollution along the Caribbean coast. Hydrocarbons extraction has resulted also in the subsiding of the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo, South America's largest lake. Venezuela is also the region's top emitter of carbon dioxide.[1]

Regional cooperation

Venezuela has pushed the creation of regional oil initiatives for the Caribbean (Petrocaribe), the Andean region (Petroandino), and South America (Petrosur), and Latin America (Petroamerica). The initiatives include assistance for oil developments, investments in refining capacity, and preferential oil pricing. The most developed of these three is the Petrocaribe initiative, with 13 nations signed agreement in 2005. Under Petrocaribe, Venezuela will offer crude oil and petroleum products to Caribbean nations under preferential terms and prices. The payment system allows for a few nations to buy oil on market value but only a certain amount is needed up front; the remainder can be paid through a 25-year financing agreement on 1% interest. The deal allows for the Caribbean nations to purchase up to 185 million barrels (29,400,000 m3) of oil per day on these terms. In addition it allows for nations to pay part of the cost with other products provided to Venezuela, such as bananas, rice, and sugar.

In 2000, Venezuela and Cuba signed an agreement, which grants Venezuelan oil supplies to Cuba.[4]

In 2006, the construction of the Trans-Caribbean gas pipeline, which will connect Venezuela and Colombia with extension to Panama (and probably to Nicaragua) began. The pipeline will pump gas from Colombia to Venezuela and, after 7 years, from Venezuela to Colombia.[20] Venezuela has also proposed the project of Gran Gasoducto del Sur, which would connect Venezuela with Brazil and Argentina.[21] There has been some discussion about constructing an oil pipeline to Colombia along the Pacific Ocean.[4]

Venezuela also exports electricity to neighboring countries. Santa Elena/Boa Vista Interconnector permits electricity export to Brazil, and Cuatricenternario/Cuestecitas Interconnector and EI Corozo/San Mateo Interconnector to Colombia.[18]

Venezuela may suffer a deterioration of its power in international affairs if the global transition to renewable energy is completed. It is ranked 151 out of 156 countries in the index of Geopolitical Gains and Losses after energy transition (GeGaLo).[22]

See also

- Petroleos de Venezuela S.A. (PDVSA)

- Renewable energy

- Trans-Caribbean pipeline

References

- "Venezuela: Energy overview". BBC. 16 February 2006. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Pierre-René Bauquis (16 February 2006). "What the future for extra heavy oil and bitumen: the Orinoco case". World Energy Council. Archived from the original on 2 April 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Bernard Mommer (April 1999). "Changing Venezuelan Oil Policy". Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Archived from the original on 26 June 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "Country Analysis Briefs. Venezuela" (PDF). Energy Information Agency. September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 January 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "PDVSA to Build Three New Refineries in Venezuela, and Industrial Info News Alert". Business Wire. 7 August 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Rovshan Ibrahimov (4 March 2007). "Nationalization Of Oil Sector In Venezuela: Action Or Reaction?". Turkish Weekly. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- Benedict Mande (26 June 2007). "Venezuela takes over US oil projects". Financial Times. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- McDermott, Jeremy (13 October 2008). "Venezuela's oil output slumps under Hugo Chavez". Telegraph. Retrieved 13 October 2008.

- Cancel, Daniel; Corina Rodrigez Pons (5 August 2010). "Venezuela Pares China Debt With $20 Billion Oil Accord". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- "Key World Energy Statistics – 2006 Edition" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 July 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- US Energy Information Administration, US imports by country of origin, accessed 8 Dec. 2013.

- OPEC, Proved petroleum reserves, accessed 8 Dec. 2013.

- US Energy Information Administration, International statistics.

- "Survey of energy resources" (PDF). World Energy Council. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - History, “Venezuela,” A&E Television Networks, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 29 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- US Energy Information Administration, “Country Analysis Briefs: Venezuela,” US Energy Information Administration, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 13 November 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link).

- "Venezuela". International energy regulation network. July 2006. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Manuel Augusto Acosta Pérez; Juan José Rios Sanchez (5 September 2004). "The electric business in Venezuela:restructuring and investment opportunities". World Energy Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2008. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "Construction starts on Colombia-Venezuela natural gas pipeline". Granma International. 8 July 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- "2006 International Pipeline Construction Report" (PDF). Pipeline & Gas Journal. August 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 12 May 2007.

- Overland, Indra; Bazilian, Morgan; Ilimbek Uulu, Talgat; Vakulchuk, Roman; Westphal, Kirsten (2019). "The GeGaLo index: Geopolitical gains and losses after energy transition". Energy Strategy Reviews. 26: 100406. doi:10.1016/j.esr.2019.100406.