Proletarianization

In Marxism, proletarianization is the social process whereby people move from being either an employer, unemployed or self-employed, to being employed as wage labor by an employer. Proletarianization is often seen as the most important form of downward social mobility[1].

Marx's concept

For Marx, the process of proletarianization was the other side of capital accumulation. The growth of capital meant the growth of the working class. The expansion of capitalist markets involved processes of primitive accumulation and privatization, which transferred more and more assets into capitalist private property, and concentrated wealth in fewer and fewer hands. Therefore, an increasing mass of the population was reduced to dependence on wage labor for income, i.e. they had to sell their labor power to an employer for a wage or salary because they lacked assets or other sources of income. The materially-based contradictions within capitalist society would foster revolution. Marx believed the proletariat would eventually overthrow the bourgeoisie as the 'last class in history'.

In modern capitalism

The classic historical study of proletarianization is E.P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class (1963), in which the author portrays the meanings, struggles and conditions of an emerging proletariat. Many intellectuals have described proletarianization in advanced capitalism as "the extension of the logic of factory labor to a large sector of services and intellectual professions."[2] In most countries, entitlement to unemployment benefits is conditional on actively looking for work, and that means people, assuming they are not sick, are compelled to seek employment either as a salaried worker or as a self-employed worker. Geographically and historically, the process of proletarianization is closely associated with urbanization because it has often involved the migration of people from rural areas where they engaged in subsistence farming, family farming and sharecropping to the cities and towns, in search of waged work and income in an office or factory (see rural flight).

A cultural explanation

A rather different explanation of proletarianization is that given by the historian Arnold J. Toynbee in his A Study of History[3] Toynbee regards proletarianization as the tendency of elite or dominant groups in societies in crisis to gradually abandon their own cultural traditions and adopt those of their own dominated proletariats as well as their external foes. He provides extensive examples across various civilizations of the workings of this process in history. Some well-known instances include the indulgence of Roman emperors such as Nero, Commodus, and Caracalla in popular displays or habits abominated by the elite historians who recorded them. Thus, unlike the Marxist conception of proletarianization discussed above, which speaks of the abasement of the working class by the dominant capitalists, Toynbee's proletarianization happens without planning and sometimes despite the dislike or opposition of the ruling groups, because it involves influence of the proletarians on the dominant rather than the reverse.

See also

- Embourgeoisement thesis

- Proletariat

- Surplus labor

- Workerism

- Deskilling

Further reading

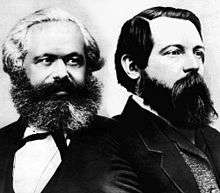

- Karl Marx, Das Kapital.

- E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Hal Draper, Karl Marx's Theory of Revolution, Vol. 2: The Politics of Social Classes.

- Barbrook, Richard (2006). The Class of the New (paperback ed.). London: OpenMute. ISBN 0-9550664-7-6. Archived from the original on 2018-08-01. Retrieved 2020-05-12.

References

- "What does proletarianization mean?". www.definitions.net. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- Debord, Guy (1967) The Society of the Spectacle, chap.14 thesis 114

- Arnold J. Toynbee (1939) A Study of History, Vol. 5, pp. 441-480

External links

| Look up proletarianization in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |