Principality of Sealand

The Principality of Sealand (/ˈsiːˌlænd/) is a micronation that claims Roughs Tower, an offshore platform in the North Sea approximately 12 kilometres (7.5 mi) off the coast of Suffolk, as its territory. Roughs Tower is a disused Maunsell Sea Fort, originally called HM Fort Roughs, built as an anti-aircraft gun platform by the British during World War II.[3][4]

Principality of Sealand | |

|---|---|

Flag

Coat of arms

| |

Motto: E Mare Libertas From the sea, Freedom | |

Anthem: "E Mare Libertas"[lower-alpha 1] | |

| |

.jpg) Sealand from above | |

| Capital | HM Fort Roughs |

| Official languages | English[1] |

| Demonym(s) | Sealander[1] |

| Organizational structure | Principality |

• Prince | Michael Bates[1] |

| Establishment | |

• Declared | 2 September 1967[1] |

| Area claimed | |

• Total | 0.004 km2 (0.0015 sq mi) (all livable space)[1] |

| Purported currency | Coins and postage stamps of the Sealand dollar (pegged to the USD)[2] |

| Time zone | GMT[1] |

Website sealandgov | |

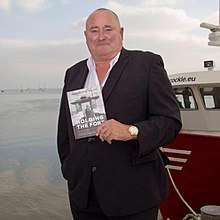

Since 1967, the decommissioned HM Fort Roughs has been occupied by the family and associates of Paddy Roy Bates, who claim that it is an independent sovereign state.[3] Bates seized it from a group of pirate radio broadcasters in 1967 with the intention of setting up his own station at the site.[5] He attempted to establish Sealand as a nation state in 1975 with the writing of a national constitution and establishment of other national symbols.[3]

While it has been described as the world's smallest country,[6][7] Sealand is not officially recognised by any established sovereign state in spite of Sealand's government's claim that it has been de facto recognised by the United Kingdom[3] and Germany.[8] The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, in force since 1994, states: "Artificial islands, installations and structures do not possess the status of islands. They have no territorial sea of their own, and their presence does not affect the delimitation of the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone or the continental shelf."[9] Since 1987, Sealand has lain within the United Kingdom's territorial waters.[10]

Bates moved to the mainland when he became elderly, naming his son, Michael, as regent. Bates died in October 2012 at the age of 91.[11] Michael lives in Suffolk,[12] where he and his sons run a family fishing business called Fruits of the Sea.[13]

History

HM Fort Roughs

In 1943, during World War II, HM Fort Roughs (sometimes called Roughs Tower) was constructed by the United Kingdom as one of the Maunsell Forts,[14] primarily to defend the vital shipping lanes in nearby estuaries against Nazi Kriegsmarine mine-laying aircraft. It consisted of a floating pontoon base with a superstructure of two hollow towers joined by a deck upon which other structures could be added. The fort was towed to a position above the Rough Sands sandbar, where its base was deliberately flooded to sink it on its final resting place. This is approximately 7 nautical miles (13 km) from the coast of Suffolk, outside the then 3 nmi (6 km) claim of the United Kingdom and, therefore, in international waters.[14] The facility was occupied by 150–300 Royal Navy personnel throughout World War II; the last full-time personnel left in 1956.[14]

Occupation and establishment

Roughs Tower was occupied in February and August 1965 by Jack Moore and his daughter Jane, squatting on behalf of the pirate station Wonderful Radio London.

On 2 September 1967, the fort was occupied by Major Paddy Roy Bates, a British subject and pirate radio broadcaster, who ejected a competing group of pirate broadcasters.[5] Bates intended to broadcast his pirate radio station – called Radio Essex – from the platform.[15] Despite having the necessary equipment, he never began broadcasting.[16] Bates declared the independence of Roughs Tower and deemed it the Principality of Sealand.[5]

In 1968, British workmen entered what Bates claimed to be his territorial waters to service a navigational buoy near the platform. Michael Bates (son of Paddy Roy Bates) tried to scare the workmen off by firing warning shots from the former fort. As Bates was a British subject at the time, he was summoned to court in England on firearms charges following the incident.[17] But as the court ruled that the platform (which Bates was now calling "Sealand") was outside British territorial limits, being beyond the then 3-nautical-mile (6 km) limit of the country's waters, the case could not proceed.[18]

In 1975, Bates introduced a constitution for Sealand, followed by a national flag, a national anthem, a currency and passports.[3]

Attack in 1978 and the Sealand Rebel Government

In August 1978, Alexander Achenbach, who describes himself as the Prime Minister of Sealand, hired several German and Dutch mercenaries to lead an attack on Sealand while Bates and his wife were in England.[8] Achenbach had disagreed with Bates over plans to turn Sealand into a luxury hotel and casino with fellow German and Dutch businessmen.[19] They stormed the platform with speedboats, Jet Skis and helicopters, and took Bates's son Michael hostage. Michael was able to retake Sealand and capture Achenbach and the mercenaries using weapons stashed on the platform. Achenbach, a German lawyer who held a Sealand passport, was charged with treason against Sealand[8] and was held unless he paid DM 75,000 (more than US$35,000 or £23,000).[20] Germany then sent a diplomat from its London embassy to Sealand to negotiate for Achenbach's release. Roy Bates relented after several weeks of negotiations and subsequently claimed that the diplomat's visit constituted de facto recognition of Sealand by Germany.[8]

Following the former's repatriation, Achenbach and Gernot Pütz established a government in exile, sometimes known as the Sealand Rebel Government or Sealandic Rebel Government, in Germany.[8]

In 1997, the Bates family revoked all Sealand passports, including those that they themselves had issued over the previous 22 years.[8] There were thought to have been about 150,000 in circulation.[3] This was due to the realisation that an international money laundering ring had appeared, using the sale of fake Sealand passports to finance drug trafficking and money laundering from Russia and Iraq.[21] The ringleaders of the operation, based in Madrid but with ties to various groups in Germany, including the rebel Sealand Government in exile established by Achenbach after the attempted 1978 coup, had used fake Sealandic diplomatic immunity and license plates. They were even reported to have sold 4,000 fake Sealandic passports to Hong Kong citizens for an estimated $1,000 each.[22]

2006 fire

On the afternoon of 23 June 2006, the top platform of the Roughs Tower caught fire due to an electrical fault. A Royal Air Force rescue helicopter transferred one person to Ipswich hospital, directly from the tower. The Harwich lifeboat stood by the Roughs Tower until a local fire tug extinguished the fire.[23] All damage was repaired by November 2006.[24]

Attempted sales

In January 2007, The Pirate Bay, an online index of digital content of entertainment media and software founded by the Swedish think tank Piratbyrån, attempted to purchase Sealand after harsher copyright measures in Sweden forced them to look for a base of operations elsewhere.[25] Between 2007 and 2010, Sealand was offered for sale through the Spanish estate company InmoNaranja,[26][27] at an asking price of €750 million (£600 million, US$906 million).[26][28][29]

Death of founder

Roy Bates died at the age of 91 on 9 October 2012; he had been suffering from Alzheimer's disease for several years. He was succeeded by his son Michael.[11][30][31] Joan Bates, Roy Bates's wife, died in an Essex nursing home at the age of 86 on 10 March 2016.[32]

Passport applications

Michael Bates stated in late 2016 that Sealand was receiving hundreds of applications for passports every day.[33]

Legal status

Sealand's claim to be an independent sovereign state is based on an interpretation of a 1968 decision of an English court, in which it was held that Roughs Tower was in international waters and thus outside the jurisdiction of the domestic courts.[3]

In 1987, the UK extended its territorial waters from 3 to 12 nautical miles (6 to 22 km). Sealand now sits inside British waters.[10] The United Kingdom is one of 165 parties to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (in force since 1994), which states in Part V, Article 60, that "Artificial islands, installations and structures do not possess the status of islands. They have no territorial sea of their own, and their presence does not affect the delimitation of the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone or the continental shelf."[9] In the opinion of law academic John Gibson, there is little chance that Sealand would be recognised as a nation because it is a man-made structure.[10]

In a 1990 court case (and a 1991 appeal) in the United States regarding registering ships in Sealand as a flag of convenience, the court ruled against allowing Sealand flagged vessels; the case was never contested by Bates.

Administration

| Prince of Sealand | |

|---|---|

Coat of Arms of Sealand | |

| Incumbent | |

| Michael since 9 October 2012 | |

| Details | |

| Heir apparent | James |

| First monarch | Roy |

| Formation | 2 September 1967 |

Irrespective of its legal status, Sealand is managed by the Bates family as if it were a recognised sovereign entity and they are its hereditary royal rulers. Roy Bates styled himself as "Prince Roy" and his wife "Princess Joan". Their son is known as "His Royal Highness Prince Michael" and has been referred to as the "Prince regent" by the Bates family since 1999.[34] In this role, he apparently serves as Sealand's acting "Head of State" and also its "Head of Government".[35]

At a micronations conference hosted by the University of Sunderland in 2004, Sealand was represented by Michael Bates's son James. The facility is now occupied by one or more caretakers representing Michael Bates, who himself resides in Essex, England.[34]

Sealand's constitution was instituted in 1974. It consists of a preamble and seven articles.[36] The preamble asserts Sealand's independence, while the articles variously deal with Sealand's status as a constitutional monarchy, the empowerment of government bureaux, the role of an appointed, advisory senate, the functions of an appointed, advisory legal tribunal, a proscription against the bearing of arms except by members of a designated "Sealand Guard", the exclusive right of the sovereign to formulate foreign policy and alter the constitution, and the hereditary patrilinear succession of the monarchy.[37]

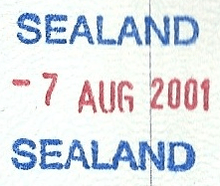

Sealand's legal system is claimed to follow British common law, and statutes take the form of decrees enacted by the sovereign.[38] Sealand has issued "fantasy passports" (as termed by the Council of the European Union), which are not valid for international travel,[39] and holds the Guinness World Record for "the smallest area to lay claim to nation status".[40] Sealand's motto is E Mare Libertas (From the Sea, Freedom). It appears on Sealandic items – such as stamps, passports and coins – and is the title of the Sealandic anthem. The anthem was composed by Londoner Basil Simonenko;[41] being an instrumental anthem, it does not have lyrics. In 2005, the anthem was recorded by the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra and released on their CD National Anthems of the World, Vol. 7: Qatar – Syria.

Business operations

Sealand has been involved in several commercial operations, including the issuing of coins and postage stamps and the establishment of an offshore Internet hosting facility, or "data haven".[42][43] Sealand also publishes an online newspaper, Sealand News.[44] In addition, a number of amateur athletes 'represent' Sealand in sporting events, including unconventional events like the World Egg Throwing Championship, which the Sealand team won in 2008.[45]

Coins and stamps

Several dozen different Sealand coins have been minted since 1972. In the early 1990s, Achenbach's German group also produced a coin, featuring a likeness of 'Prime Minister Seiger'.[46] Sealand's coins and postage stamps are denominated in 'Sealand dollars', which it deems to be at parity with the US dollar.[47] Sealand first issued postage stamps in 1969, and issues through 1977. No further stamps were produced until 2010. Sealand is not a member of the Universal Postal Union, therefore its inward address is a PO Box in the British borough of Ipswich.[48] Once an item is mailed to Sealand's tourist and government office, it will then be taken to Sealand. Sealand only has one street address, The Row.[49]

A Sealand mailing address looks like this:[49]

Bureau of Internal Affairs

5, The Row

SEALAND 1001

(c/o Sealand Post Bag, IP11 9SZ, UK)

This Felixstowe post code was terminated by the Royal Mail in December 2018.[50]

HavenCo

In 2000, worldwide publicity was created about Sealand following the establishment of a new entity called HavenCo, a data haven, which effectively took control of Roughs Tower itself. Ryan Lackey, Haven's co-founder and a key participant in the country, left HavenCo under acrimonious circumstances in 2002, citing disagreements with the Bates family over management of the company. The HavenCo website went offline in 2008.[51]

Sports

Sealand is not recognised by any major international sporting body, and its population is insufficient to maintain a team composed entirely of Sealanders in any team sport. However, Sealand claims to have official national athletes, including non-Sealanders. These athletes take part in various sports, such as curling, mini-golf, football, fencing, ultimate, table football and athletics, although all its teams compete out of the country.[52] The Sealand National Football Association is an associate member of the Nouvelle Fédération-Board, a football sanctioning body for non-recognised states and states not members of FIFA. It administers the Sealand national football team. In 2004 the national team played its first international game against Åland Islands national football team, drawing 2–2.[53]

Sealand claims that its first official athlete was Darren Blackburn of Oakville, Ontario, Canada, who was appointed in 2003. Blackburn has represented Sealand at a number of local sporting events, including marathons and off-trail races.[54] In 2004, mountaineer Slader Oviatt carried the Sealandic flag to the top of Muztagh Ata.[55] Also in 2007, Michael Martelle represented the Principality of Sealand in the World Cup of Kung Fu, held in Quebec City, Canada; bearing the designation of Athleta Principalitas Bellatorius (Principal Martial Arts Athlete and Champion), Martelle won two silver medals, becoming the first-ever Sealand athlete to appear on a world championship podium.[56]

In 2008, Sealand hosted a skateboarding event with Church and East sponsored by Red Bull.[57][58][59]

In 2009, Sealand announced the revival of the Sealand Football Association and their intention to compete in a future Viva World Cup. Scottish author Neil Forsyth was appointed as President of the Association.[60] Sealand played the second game in their history against Chagos Islands on 5 May 2012, losing 3–1. The team included actor Ralf Little and former Bolton Wanderers defender Simon Charlton.[61]

In 2009 and 2010, Sealand sent teams to play in various ultimate club tournaments in the United Kingdom, Ireland and the Netherlands. They came 11th at UK nationals in 2010.[62]

In 2012 Sealand was represented in the flat track variant of roller derby, by a team principally composed of skaters from the South Wales area.[63]

Sealand played a friendly match in aid of charity against an "All Stars" team from Fulham F.C. on 18 May 2013, losing 5–7.[64][65]

On 22 May 2013, the mountaineer Kenton Cool placed a Sealand flag at the summit of Mount Everest.[66]

In 2015, the runner Simon Messenger ran a half-marathon on Sealand as part of his "round the world in 80 runs" challenge.[67]

In August 2018 competitive swimmer Richard Royal became the first person to swim the 12 km from Sealand to the mainland, finishing in 3 hrs 29 mins. Royal visited the platform before the swim, getting his passport stamped. He entered the water from the 'bosuns chair', signalling the start of the swim, and finished on Felixstowe beach. It was accredited as an inaugural and therefore current world and British record by the World Open Water Swimming Association (WOWSA)[68] and the British Long Distance Swimming Association (BLDSA).[69] Royal was subsequently awarded with a Sealand Knighthood by Prince Michael.[70] The swim was the subject of a short documentary film entitled Escape from Sealand.[71]

See also

Notes

- By Basil Simonenko

References

- "Information on the Principality of Sealand including Bates Family, GDP, Constitution" (PDF). Artists' Association MUU. Amorph Summit of Micronations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- "Information on the Principality of Sealand including Bates Family, GDP, Constitution" (PDF). Artists' Association MUU. Amorph Summit of Micronations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

- "History of Sealand". The Principality of Sealand. Archived from the original on 1 October 2015.

- Jacobs, Frank (20 March 2012). "All Hail Sealand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Ryan, John; Dunford, George; Sellars, Simon (2006). Micronations. Lonely Planet. p. 9. ISBN 1-74104-730-7.

- "Skateboarding the World's Smallest Country: Red Bull All Access". Archived from the original on 5 December 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "JOURNEYS – THE SPIRIT OF DISCOVERY: Simon Sellars braves wind and waves to visit the unlikely North Sea nation of Sealand". The Australian. 10 November 2007. Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- Ryan, John; Dunford, George; Sellars, Simon (2006). Micronations. Lonely Planet. p. 11. ISBN 1-74104-730-7.

- "Article 60: Artificial islands, installations and structures in the exclusive economic zone" (PDF). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. New York: United Nations. p. 45. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 November 2015.

- Ward, Mark (5 June 2000). "Offshore and offline?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 22 February 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- "Self-declared prince of sovereign principality of Sealand dies aged 91". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- Ryan, John; Dunford, George; Sellars, Simon (2006). Micronations. Lonely Planet. pp. 9–12. ISBN 1-74104-730-7.

- Milmo, Cahal (18 March 2016). "Sealand's Prince Michael on the future of an off-shore 'outpost of liberty'". Independent. Retrieved 30 December 2017.

- Zumerchik, John (2008). Seas and Waterways of the World: An Encyclopedia of History, Uses, and Issues. ABC-CLIO Ltd. p. 563. ISBN 978-1-85109-711-1.

- Gould, Jack (25 March 1966). "Radio: British Commercial Broadcasters Are at Sea; Illegal Programs Are Beamed From Ships". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- Edwards, Chris; Parkes, James (19 October 2000). "Radio Essex" and "Britains Better Music Station" Archived 17 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Off Shore Echoes. Retrieved 11 May 2011

- "Welcome to Sealand. Now Bugger Off". Wired News. July 2000. Archived from the original on 30 April 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- Regina v. Paddy Roy Bates and Michael Roy Bates, The Shire Hall, Chelmsford, 25 October 1968. "Regina v. Paddy Roy Bates and Michael Roy Bates". The Shire Hall, Chelmsford. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Adam Payne. "WELCOME TO SEALAND: The utterly bizarre independent micronation that's been sitting off the British coast for over 50 years". Business Insider.

- "Attempt to free captive from private 'island' fails". The Times. 5 September 1978. p. 3.

- Gooch, Adela (12 April 2000). "Police swoop on Sealand crime ring". Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 13 February 2019 – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Money Laundering: Global fraudsters use sea fortress as passport to". The Independent. 23 September 1997.

- "Blaze at offshore military fort". BBC. 23 June 2006. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Church and East renovation completion". Church and East. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

- Graham, Flora (16 February 2009). "Technology: How The Pirate Bay sailed into infamy". BBC News. Archived from the original on 19 April 2009. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- "'Smallest state' seeks new owners". BBC. 8 January 2007. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- "Tiny North Sea tax haven for sale". Sydney, Australia: ABC News. Agence France-Presse. 8 January 2007. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011.

- "£65m price tag for Sealand tenancy". Evening Star. Ipswich. 6 January 2007. Archived from the original on 11 January 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2007.

- "For sale, World's smallest country". The Sydney Morning Herald. 8 January 2007. Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 8 January 2007.

- Yardley, William (13 October 2012). "Roy Bates, Bigger-Than-Life Founder of a Micronation, Dies at 91". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Van Gilder Cooke, Sonia (12 October 2012). "RIP Paddy Roy Bates, the Prince of Sealand". Time. New York. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

- Milmo, Cahal (14 March 2016). "'Princess Joan of Sealand' has died aged 86". The Independent. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

- "Tiny principality of Sealand swamped by passport applications after Brexit and Trump wins". Express.co.uk. 17 January 2017. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2019.

- "Information on Sealand's royal family". Sealand News. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 13 November 2007.

- Ryan, John; Dunford, George; Sellars, Simon (2006). Micronations. Lonely Planet. p. 8. ISBN 1-74104-730-7.

- "The Principality of Sealand – Become a Lord, Lady, Baron or Baroness". sealandgov.org. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Information on the Principality of Sealand including Bates Family, GDP, Constitution" (PDF). Artists' Association MUU. Amorph Summit of Micronations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2005. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- "The Principality of Sealand statutory notices". Government of the Principality of Sealand. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- Council of the European Union – Schengen Visa Working Party – Table of travel documents, p. 36

- Guinness World Records 2008. Guinness World Records. 2007. p. 131. ISBN 978-1-904994-18-3.

- "Sealandic National Anthem". Nationalanthems.info. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- "Stop signs on the web; The battle between freedom and regulation on the Internet". The Economist. 13 January 2001. p. 1. Archived from the original on 6 November 2015.

- Grimmelmann, James (27 March 2012). "Death of a data haven: cypherpunks, WikiLeaks, and the world's smallest nation". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015.

- "Sealand News". Archived from the original on 10 November 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- "Sealand wins sporting accolade". Sealand News. 30 October 2008. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- "The Imperial Collection – Principality of Sealand". Empire of Atlantium. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- "Principality of Sealand". Government of the Principality of Sealand. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Royal Mail address for Sealand". Royal Mail. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- "Principality Notice PN 037/10: Update of visit and immigration regulations". Sealandgov.org. 28 September 2010. Archived from the original on 22 May 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- "Interesting Information for Felixstowe, IP11 9SZ Postcode". StreetCheck.

- Stackpole, Thomas (21 August 2013). "The World's Most Notorious Micronation Has the Secret to Protecting Your Data From the NSA". Mother Jones. San Francisco. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Homepage of the Sealand National Football Team" (in Danish). Sealand National Football Team. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2007.

- "IBWM Fantasy football micronation style". IBWM. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "Principality Notice PN 025/04: International Sporting Activities update". Government of the Principality of Sealand. Archived from the original on 11 September 2015. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- Kowalski, Kenneth R., ed. (24 November 2009). "Bill 50: Electric Statutes Amendment Act, 2009" (PDF). Alberta Hansard. Edmonton, Canada: Province of Alberta. p. 2019. ISSN 0383-3623. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2013.

- "Program Souvenir Legal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- "Skate Sports". Red Bull. Redbullskateboarding.com. 15 October 2008. Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2009.

- "Skateboarder erobern Seefestung vor der englischen Küste". 10 September 2008. Archived from the original on 24 December 2008. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- "Welcome to Church and East". Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- "Principality of Sealand to have National Football Team". PR Log. 23 December 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2010.

- "Ralf Little gets an international cap for Sealand". BBC Sport. 7 May 2012. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 7 May 2012.

- WebFox (10 February 2011). "Principality of Sealand 2010 Review". Glasgow Ultimate. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- "Sealand to form roller derby team Sealand official website". Archived from the original on 8 May 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Sealand will play Fulham F.C. in a friendly match on May 18th, 2013". Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- "Fulham All Stars 7-5 Sealand All Stars". 18 May 2013. Archived from the original on 15 September 2013. Retrieved 18 September 2013.

- Ben Fogle [@Benfogle] (31 May 2013). "Lord Fogle of Sealand thanks @kentoncool for taking the @sealandgov flag to Everest. @edsheeran gig next? Please Ed" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Messenger, Simon (11 September 2015). "How I ran a half marathon on Sealand, the fortress 'nation' in the middle of the sea". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Royal, Sir Richard (12 September 2018). "My certificate has arrived from the World Open Water Swimming Association recognising my @SealandGov @AspireCharity swim. It will go nicely in a frame next to my Knighthood . Now I'm just awaiting confirmation from @BLDSAswimpic.twitter.com/Weg4MN9lDY".

- Royal, Sir Richard (4 December 2018). "Finally, officially the first person ever to swim from @SealandGov to the UK mainland at Felixstowe. @BLDSAswimpic.twitter.com/tJGdAbEhfu".

- "Arise Sir Richard: Sealand swimmer knighted". Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "Escape from Sealand". YouTube. 21 February 2019. Retrieved 16 March 2020.

Further reading

- Cogliati-Bantz, Vincent. "My Platform, My State: the Principality of Sealand in International Law" Archived 14 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine (2012) 18 (3) Journal of International Maritime Law 227–250

- Connelly, Charlie. Attention All Shipping: A Journey Round The Shipping Forecast, Abacus, 2005. ISBN 0-349-11603-2.

- Conroy, Matthew. "Note: Sealand – The Next New Haven?" Suffolk Transnational Law Review, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 127–152. Winter 2003. ISSN 1072-8546. Issue table of contents page Archived 3 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine.

- Fogle, Ben. Offshore: In Search of an Island of My Own, Penguin Books, 2007. ISBN 978-0-14-102434-9.

- Garfinkel, Simson. "Welcome to Sealand. Now Bugger Off". Wired. July 2000. Vol. 8.07.

- Gilmour, Kim. "Sealand: Wish You Were Here?" Internet Magazine. August 2002.

- Goldsmith, Jack, & Wu, Tim. Who Controls the Internet?: Illusions of a Borderless World, 2006, ISBN 0-19-515266-2.

- Grimmelmann, James. "Sealand, HavenCo, and the Rule of Law" Archived 4 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, March 2012, University of Illinois Law Review, Volume 2012, Number 2

- "License Plates of Sealand (Great Britain)". License plates of the world. Web. 28 December 2009.

- McCullagh, Declan (5 August 2003). "Has 'haven' for questionable sites sunk?". CNET News.com. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- Menefee, Samuel Pyeatt. "Republics of the Reefs: Nation-Building on the Continental Shelf and in the World's Oceans". California Western International Law Journal, vol. 25, no. 1. Fall 1994.

- Miller, Marjorie, & Boudreaux, Richard. "A Nation for Friend and Faux". Los Angeles Times. 7 June 2000. p. A-1.

- Slapper, Gary. "How a law-less 'data haven' is using law to protect itself". The Times. 8 August 2000. p. 3.

- Strauss, Erwin S. How to Start Your Own Country, 2nd ed. Port Townsend, WA: Breakout Productions, 1984. ISBN 1-893626-15-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sealand. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Principality of Sealand. |

- Official website

- Principality of Sealand at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Sealand National Anthem – MIDI file on nationalanthems.info

- Blueprint of the platform

- First International Football Match

- In Living Memory Series 16 Episode 1 (Radio 4 programme)