Patron and priest relationship

The patron and priest relationship, also simply written as priest-patron or cho-yon (Tibetan: མཆོད་ཡོན་, Wylie: mchod yon ; Chinese: 檀越关系; pinyin: Tányuè Guānxì) is the symbolic relationship between a religious figure and a lay patron in the Tibetan ideology or political theory. "chöyön" is an abbreviation of two words: chöney, "that which is worthy of being given gifts and alms" (for example, a lama or a deity), and yöndag, "he who gives gifts to that which is worthy" (a patron).[1]

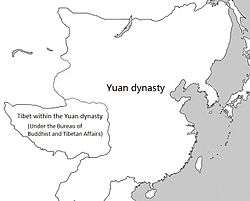

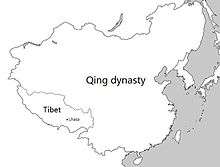

This concept has been used by, for example, the 13th Dalai Lama to describe the relationship between Tibetan lamas and Mongol khans or Manchu emperors of the Qing dynasty. According to this concept, in the case of Yuan rule of Tibet in the 13th and 14th centuries, Tibetan Lamas provided religious instruction; performed rites, divination and astrology, and offered the khan flattering religious titles like "protector of religion" or "religious king"; the khan (Kublai and his successors), in turn, protected and advanced the interests of the "priest" ("lama"). The lamas also made effective regents through whom the Mongols ruled Tibet.[2] Also in the case of Qing rule of Tibet, for those who espouse the idea, the Dalai Lama and the Manchu emperor stood respectively as spiritual teacher and lay patron rather than subject and lord.

Nevertheless, according to Elliot Sperling, an expert on the history of Tibet and Tibetan-Chinese relations at Indiana University, the Tibetan concept of a "priest-patron" religious relationship governing Sino-Tibetan relations to the exclusion of concrete political subordination is itself a rather recent construction. He writes that the patron and priest relationship coexisted with Tibet's political subordination to the Yuan and Qing dynasties.[3] During the 1913 Simla Conference, the 13th Dalai Lama's negotiators used the "priest and patron relationship" as a rhetorical device to explain the lack of any clearly demarcated boundary between Tibet and the rest of China (as a religious benefactor, the Qing did not need to be hedged against).[4]

See also

- Mongol conquest of Tibet

- Sino-Tibetan relations during the Ming dynasty

- Tibetan sovereignty debate

References

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. (1991). "A History of Modern Tibet, 1913-1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State". University of California Press. ISBN 9780520911765. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- "The Snow Lion and the Dragon: China, Tibet, and the Dalai Lama" by Melvyn C. Goldstein, p3

- "The Tibet-China Conflict: History and Polemics" by Elliot Sperling, p30

- Chang, Simon T. "A ‘realist’ hypocrisy? Scripting sovereignty in Sino–Tibetan relations and the changing posture of Britain and the United States." Asian Ethnicity 12.3 (2011): 323-335.

Further reading

- Cüppers, Christopher, ed. (2004). The Relationship Between Religion and State (chos srid zung 'brel) In Traditional Tibet: Proceedings of a Seminar Held in Lumbini, Nepal, March 2000. LIRI Seminar Proceeding Series. 1. Lumbini: Lumbini International Research Institute. ISBN 99933-769-9-X.